A Guide to Coastal Public Rescue Equipment Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

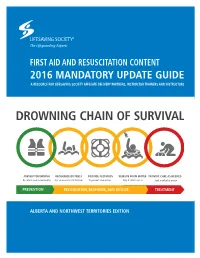

Drowning Chain of Survival

FIRST AID AND RESUSCITATION CONTENT 2016 MANDATORY UPDATE GUIDE A RESOURCE FOR LIFESAVING SOCIETY AFFILIATE DELIVERY PARTNERS, INSTRUCTOR TRAINERS AND INSTRUCTORS DROWNING CHAIN OF SURVIVAL PREVENT DROWNING RECOGNIZE DISTRESS PROVIDE FLOTATION REMOVE FROM WATER PROVIDE CARE AS NEEDED Be safe in and around water Ask someone to call for help To prevent submersion Only if safe to do so Seek medical attention PREVENTION RECOGNITION, RESPONSE, AND RESCUE TREATMENT ALBERTA AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES EDITION FIRST AID AND RESUSCITATION CONTENT 2016 MANDATORY UPDATE GUIDE FIRST AID AND RESUSCITATION CONTENT 2016 MANDATORY UPDATE GUIDE A RESOURCE FOR LIFESAVING SOCIETY AFFILIATE DELIVERY A RESOURCE FOR Lifesaving SOCIETY AFFILIATE delivery partners, PARTNERS, INSTRUCTOR TRAINERS AND INSTRUCTORS instructor TRAINERS AND instructors Published by the Lifesaving Society, First Printing December 2018 _____________________________________________________________ Copyright 2016 by the Royal Life Saving Society Canada. Reproduction, by any means, of materials contained in this book is prohibited unless authorized by the publisher. Requests should be directed to the Alberta and Northwest Territories office (see back cover for contact information). The Lifesaving Society is Canada’s lifeguarding expert. The Society works to prevent drowning and water-related injury through its training programs, Water Smart® public education initiatives, water-incident research, aquatic safety management services, and lifesaving sport. Annually, well over 1,200,000 Canadians participate in the Society’s swimming, lifesaving, lifeguard, and leadership training programs. The Society sets the standard for aquatic safety in Canada and certifies Canada’s National Lifeguards. The Society is an independent, charitable organization educating Canadian lifesavers since the first Lifesaving Society Bronze Medallion Award was earned in 1896. -

Assisting Drowning Victims: Effective Water Rescue Equipment for Lay-Responders

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education Volume 10 Number 4 Article 8 2-1-2019 Triennial Scientific Review: Assisting Drowning Victims: Effective Water Rescue Equipment for Lay-responders Angela K. Beale-Tawfeeq Rowan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare Part of the Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons, Exercise Science Commons, Health and Physical Education Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, Outdoor Education Commons, Sports Sciences Commons, Sports Studies Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Beale-Tawfeeq, Angela K. (2019) "Triennial Scientific Review: Assisting Drowning Victims: Effective Water Rescue Equipment for Lay-responders," International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education: Vol. 10 : No. 4 , Article 8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.10.04.08 Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol10/iss4/8 This Scientific Literature Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Triennial Scientific Review: Assisting Drowning Victims: Effective Water Rescue Equipment for Lay-responders Cover Page Footnote Thanks to members of the aquatic sub-council of the American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council who provided feedback and editing on this scientific er view. This scientific literature review is available in International -

Aquatic Certifications for NYS Bathing Facilities (Fact Sheet)

AQUATIC CERTIFICATIONS for NYS Bathing Facilities Fact Sheet – April 2021 (Go to www.health.ny.gov to view most current certification list) Standards for aquatic/lifeguard certifications are contained in New York State Sanitary Codes (SSC) Subpart 6-1, Section 6-1.31, Swimming Pools; Subpart 6-2, Section 6-2.20, Bathing Beaches; and Subpart 7-2, Section 7-2.5(g), Children’s Camps. When the SSC requires "lifeguard supervision" or a "qualified lifeguard" at a bathing facility, an approved lifeguard certification SPECIFIC to the type of bathing facility is required. NOTE: • All lifeguards must possess separate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) certification in an approved course listed on the NYS CPR fact sheet unless otherwise indicated in the below table. All CPR certificates are valid for 1 year from course completion, regardless of the expiration date noted on the card. • Lifeguard certifications shall be valid for the time period specified by the certifying agency, but may not exceed a con secutive 3-year period from course completion. Multiyear lifeguard certifications that include CPR require a CPR certification each year. • Children's camp lifeguards must be at least 17 years of age, except; − A maximum of 50% of the required lifeguards on duty may be 16 years of age; − Lifeguards for wilderness swimming must be at least 18 years of age. • Supervising lifeguards must possess at least Supervision Level IIb certification, be at least 18 years old, and have at least 2 seasons of lifeguarding experience. ACCEPTED COURSES SUPERVISION LEVEL Marked boxes indicate acceptability Level II b Level I Pool & Level II a PROVIDER CERTIFICATION TITLE Surf Pool Only Beach American Red Cross (ARC) Lifeguarding/First Aid/CPR/AED* X LIFEGUARDING AND FIRST AID CERTIFICATIONS ARE Lifeguarding, Waterpark Skills/First Aid/CPR/ X VALID FOR 2 YEARS FROM DATE OF ISSUANCE. -

A Lifeguard's Beach Safety Tips

A Lifeguard’s Beach Safety Tips by Sgt. Ed Fisher Special to the Dispatch The writer is a 17-year veteran of the Beach patrol. In the off-season, he is an elementary school teacher in Montgomery County. The OCBP consist of over 200 men and women dedicated to ocean rescue and maintaining a safe and orderly environment on Ocean City’s beach. The Sure Rescue Technicians guard the beach seven days a week from 10 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Studying the waves helps safety September 12, 2008 The Dispatch/Maryland Coast Dispatch Recently a kite surfer tried surfing in a hurricane and ended up getting blown into the side of a building. An accident like this does not happen because of bad luck. An accident like this happens because of poor decision making, not knowing your sport, and not respecting the elements. I mean is it really surprising that a kite that was flying in a hurricane got out of control? The idea here is that everyone entering the surf should have more common sense than this and take some basic precautions. The first precaution begins on the beach. People should spend at least 15 minutes on the beach surveying the conditions. Often people come out to the beach and see a calm ocean. As soon as they attempt to swim they find themselves confronted with a dangerous set of waves or strong currents they were not aware of. Be sure to know what the conditions are before entering the water. The daily conditions of the ocean are governed by the swell direction, wind velocity, and ocean bottom. -

International Life Saving Federation World Drowning Report 2007

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education Volume 1 Number 4 Article 8 11-1-2007 International Life Saving Federation World Drowning Report 2007 International Life Saving Federation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare Recommended Citation International Life Saving Federation (2007) "International Life Saving Federation World Drowning Report 2007," International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education: Vol. 1 : No. 4 , Article 8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.01.04.08 Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol1/iss4/8 This Position Statement is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. International Life Saving Federation: International Life Saving Federation World Drowning Report 2007 SPECIAL SECTION International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 2007, 1, 381-401 International Life Saving Federation World Drowning Report 2007 Edition Published September 27, 2007, by The International Life Saving Federation Gemeenteplein 26, 3010 Leuven, Belgium E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ilsf.org The International Life Saving Federation (www.ilsf.org) is the global confederation of national nonprofit lifesaving organizations. Published by ScholarWorks@BGSU, 2007 381 1 International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, Vol. 1, No. 4 [2007], Art. 8 382 International Life Saving Federation Preface: The International Life Saving Federation The International Life Saving Federation is a global, non-profit federation of over 100 national lifesaving organisations around the world. The Federation (ILS) leads the worldwide effort to reduce injury and death in, on, or around the water. -

Air Stand-Up Paddle Water Rescue Table: How Can It Help to the Lifeguard?

Rev.int.med.cienc.act.fís.deporte - vol. 18 - número 69 - ISSN: 1577-0354 Palacios-Aguilar, J.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; López-García, S.; Carpentier, M. y Abelairas-Gómez, C. (2018). Tabla Air Stand-Up Paddle de rescate acuático: ¿cómo puede ayudar al socorrista? / Air Table Stand-Up Paddle Water Rescue: How Can You Help The Lifeguard? Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte vol. 18 (69) pp. 185-197 Http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista69/arttabla880.htm DOI: https://doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2018.69.012 ORIGINAL AIR STAND-UP PADDLE WATER RESCUE TABLE: HOW CAN IT HELP TO THE LIFEGUARD? TABLA AIR STAND-UP PADDLE DE RESCATE ACUÁTICO: ¿CÓMO PUEDE AYUDAR AL SOCORRISTA? Palacios-Aguilar, J.¹; Barcala-Furelos, R.²; López-García, S.³; Carpentier, M.⁴; Abelairas-Gómez, C.⁵ 1 Facultad de Ciencias del Deporte y la Educación Física. Universidad de A Coruña. A Coruña (Spain) [email protected] 2 Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación y del Deporte. Universidad de Vigo. Pontevedra (Spain) [email protected] 3 Facultad de Educación. Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. Salamanca (Spain) [email protected] 4 Universidad de Brest. Brest (France) [email protected] 5 Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud. Universidad Europea del Atlántico. Santander (Spain) [email protected] Spanish-English translator: Beatriz Palacios Castillo, [email protected] Código UNESCO / UNESCO code: 3212 Salud Publica / Public Health Clasificación Consejo de Europa / Council of Europe Classification: 17. Otras (Salvamento y Socorrismo) / Other (Lifesaving). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the collaboration of the professional life guards from the town of Puerto del Rosario in Fuerteventura’s island and their coordinator Camilo Lorenzo. -

Lifeguard Effectiveness: a Report of the Working Group

Lifeguard Effectiveness: A Report of the Working Group Editors: Christine M. Branche, Ph.D. Steven Stewart, M.S. Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Department of Health and Human Services Lifeguard Effectiveness: A Report of the Working Group is a publication of the National Center for Injury Prevention and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Jeffrey P. Koplan, M.D., M.P.H., Director National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Sue Binder, M.D., Director Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention Christine M. Branche, Ph.D., Director Production services were provided by staff of the Management Analysis and Services Office, CDC. Suggested Citation: Branche CM, Stewart S. (Editors). Lifeguard Effectiveness: A Report of the Working Group. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2001. ii Lifeguard Effectiveness: A Report of the Working Group Table of Contents Contributing Authors ................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary.................................................................................................................... vii Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 A Brief History and Background of Lifeguarding -

United States Lifeguarding Standards Coalition

United States Lifeguard Standards Page 2 of 67 January 2011 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Sincere appreciation is extended to all of the individuals who dedicated their time and expertise to the development of the first outcomes and recommendations of the United States Lifeguard Standards Coalition. Special thanks is extended to the National Swimming Pool Foundation, Colorado Springs, Co., for the generous donation that funded this project. The contributions and commitment to excellence by all involved made this project possible. United States Lifeguard Standards Page 3 of 67 January 2011 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The Problem History of Collaboration Establishment of the Coalition Participants and Responsibilities Scope of the Process PROCESS AND METHODOLOGY Evidence-Based Process Scientific Review and Evidence Grading Review Process EVIDENCE EVALUATIONS: THE QUESTIONS Scanning Techniques Vigilance Inattentional Blindness Visual and Behavioral Cues Breaks (Interruptions of Duty) Age Hearing Vision Physical Competency Use of Equipment Airway Suction Cervical Spine Injury Oxygen Online Learning REFERENCES United States Lifeguard Standards Page 4 of 67 January 2011 Abbreviations ABC Airway, breathing, and circulation AED Automated external defibrillator AHA American Heart Association ARC American Red Cross BLS Basic life support CI Confidence interval COI Conflict of interest CoSTR Consensus on Resuscitation Science and Treatment Recommendations CPR Cardiopulmonary resuscitation EMS Emergency medical systems EMT Emergency medical technician ILCOR International -

Essential First Aid MANUAL New Zealand Red Cross Now Carries the Most Comprehensive Range of First Aid Kits in New Zealand

Essential First Aid MANUAL New Zealand Red Cross now carries the most comprehensive range of first aid kits in New Zealand. The range offers solutions for home, car, sport, business, kitchen, grab bag and much, much more. For more information go to redcrossshop.org.nz OUR PRODUCTS Motokit Biohazard Workplace Catering Eye Wash Grab and Go 0800 233 243 redcross.org.nz SPECTRA FIRST AID SYSTEM® SPECTRA FIRST AID SYSTEM® ORDER NOW! SPECTRA ® SPECTRA FIRST AID SYSTEM FIRST AID SYSTEM® SPECTRA ® SPECTRA FIRST AID SYSTEM FIRST AID SYSTEM® SPECTRA ® SPECTRA FIRST AID SYSTEM FIRST AID SYSTEM® A practical, convenient and innovative new system, designed to effectively equip your workplace with first aid, ensuring your legal requirements are met. All workplaces are unique and the first aid requirements are too. Choosing from six individual options will let you create the Workplace First Aid System your risk assessment demands. ɠ Workplace blue for food areas ɠ Online portal for ordering replacement stock ɠ Low, medium and high risk first aid courses ɠ App and online learning FOR MORE INFORMATION: [email protected] Sending for help If you are not sure whether emergency services are needed, call anyway. They can help you decide. Remain calm. Take a deep breath, call an ambulance. In New Zealand, call 111. Know the emergency numbers for where you are or where you are going. Emergency numbers: Always send for help as soon as possible. Once you have made contact, LISTEN carefully and answer the questions. The following information will be required by the dispatcher: ɠ Where the emergency happened ɠ The telephone number you are calling from ɠ What has happened ɠ The number of people who need help Quick assessment If you are able to quickly assess the casualty, obtain the following information: ɠ Is the casualty awake? ɠ Can the casualty talk to you? ɠ Is the casualty breathing normally? ɠ Is the casualty bleeding severely? Tell the dispatcher what you find in your quick assessment. -

Surf Lifeguard Training Manual

Surf Lifeguard Training Manual 2017 Begin In 1910 Surf Lifeguards began providing beach patrols. It wasn’t just about making our beaches safer, it was about the increasing popularity of our beaches for recreation. There has been a lot of change in the last 100 years and today Surf Life Saving is about more than just patrolling between the flags. Coastal development has opened up new beaches and new walk ways lead people to different parts of our beaches today. Windsurfers, surfing, boogie boards – even wetsuits which we take for granted today, have all had a significant impact on when and how people use our beaches. Today we provide patrols at more than 80 of New Zealand’s most popular beaches, but it’s just part of what we do. Public education, event safety services, search and rescue and working with councils to ensure effective and consistent signage are all part of our Lifesaving plan to achieve our purpose. Membership Today there are nearly 18,000 members across 74 Clubs. Each year more than 800 new Lifeguards are qualified. Behind every Lifeguard, a coach, an instructor, and committee members all have an important role to play. The oppurtunities available to you as a member of a surf lifesaving club are extraordinary. Once you have your Lifeguard Award, you can advance through the lifeguard programme in which ever direction you choose – First Aid, Inflatable Rescue Boat (IRB), Lifeguard development. You are also able to participate in our sport programme and put your skills on the line against others – be it beach sprints, swimming, surf boats or IRBs. -

Marina Drownings, Life Rings, and Safety Ladders

Marina Drownings, Life Rings, and Safety Ladders Carl F. Wolf , CMM, CMI Provided by: This book contains a complete copy of the study as published in January 2018. This content is the property of Robson Foren- sic and is protected by copyright, trademark, and other laws of the United States. This content shall not be modified, reprint- ed, or used in any way without the express written permission of Robson Forensic, Inc. All rights are reserved. Robson Forensic and the author of this study reserve the right to correct or amend this study as additional information becomes available. Robson Forensic cannot assume any respon- sibility for omissions, errors, misprinting, or ambiguity contained within this publication and shall not be held liable in any degree for any loss or injury caused by such omission, error, misprinting or ambiguity presented in this publication. -1- www.robsonforensic.com Contents Introduction 5 Research Findings 7 Highlights of Drowning Data 8 Prevention 11 Existing Guidelines, Regulations, and Standards 13 Life Rings 13 Safety Ladders 16 Further Notes 18 Fire Extinguishers 20 Recommendations 21 Appendix A 25 Appendix B 41 Carl Wolf, CMM, CMI 57 © Robson Forensic -2- -3- www.robsonforensic.com Introduction This research project will explore the magnitude and frequency of per- sons unintentionally falling and subsequently drowning in marina waters, and specifically whether this danger has been properly addressed. In recent years, I have consulted with numerous marinas, both domestic and abroad. The majority of these marinas were located within the United States. Outside of the continental U.S., I have consulted with marinas in regions that include Canada, U.S. -

Lifesaving South Africa Patrol Guidelines 2020

PATROL GUIDELINES - 2020 LIFESAVING SOUTH AFRICA PATROL GUIDELINES 2020 www.lifesaving.co.za www.lifesaving.co.za LIFESAVING SOUTH AFRICA LIFESAVING SA GUIDELINES FOR PATROL’S A Patrollers primary duty is to ensure the safety of persons within an area which has been deemed safe for public swimming. All communities have an expectation of safe water use. LSA has a responsibility to meet the challenge of this expectation by patrolling and supplying a lifesaving service, and administering first aid as required. Members joining the association need to be made aware of their responsibility in the maintaining efficient duties. Your knowledge of rescue techniques and the training in these skills will ensure safe bathing for the community. In addition, lifeguards must act as good ambassadors for the Association. All members required to do duty in a club should be allocated into squads so that everyone is aware of when it is their turn to protect the bathers. At the head of each squad is the Squad Leader. He should be a responsible, experienced lifeguard who can control the aquatic facility, beach, pool, open water or leisure park facility, and deal with people, both public and squad members. He controls the allocation of the squad members to their duties. The safe swimming area must be carefully checked by the duty squad for possible danger spots; once a safe area has been identified clear bathing signs must be displayed. The size of the safe swimming area depends on the duty squad, number of swimmers and the environment PATROL ACTIVITIES Various patrol activities may be employed in the efforts to ensure the safety of the swimmers: Traditional method: Between the red and yellow flags This is the most common type of patrol and simply requires the setting of the flags at the safest place on the beach.