Oak Silkworm, Antheraea Pernyi-Specifically, Its Separation By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Response to Sex-Pheromone Loss in the Large Silk Moth

I exp Biol 137, 29-38 (1988) Printed in Great Britain 0 The Company of Biologists Limited 1988 MEASURED BEHAVIOURAL LATENCY! IN RESPONSE TO SEX-PHEROMONE LOSS IN THE LARGE SILK MOTH *Ç ANTHERAEA POLYPHEMUS BYT C. BAKER ; Division of Toxicology and Physiology, Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA AND R G VOGT* Institute for Neuroscience, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA Accepted 15 February 1988 Summary Males of the giant silk moth Antheraea polyphemus Cramer (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) were video-recorded in a sustained-flight wind tunnel in a constant plume of sex pheromone The plume was experimentally truncated, and the moths, on losing pheromone stimulus, rapidly changed their behaviour from up- tunnel zig-zag flight to lateral casting flight The latency of this change was in the range 300-500 ms Video and computer analysis of flight tracks indicates that these moths effect this switch by increasing their course angle to the wind while decreasing their air speed Combined with previous physiological and biochemical data concerning pheromone processing within this species, this behavioural study supports the argument that the temporal limit for this behavioural response latency is determined at the level of genetically coded kinetic processes located within the peripheral sensory hairs Introduction The males of numerous moth species have been shown to utilize two distinct behaviour patterns during sex-pheromone-mediated flight In the presence of pheromone they zig-zag upwind, making -

Polyphemus Moth Antheraea Polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W

EENY-531 Polyphemus Moth Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W. Hall2 Introduction Distribution The polyphemus moth, Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer), Polyphemus moths are our most widely distributed large is one of our largest and most beautiful silk moths. It is silk moths. They are found from southern Canada down named after Polyphemus, the giant cyclops from Greek into Mexico and in all of the lower 48 states, except for mythology who had a single large, round eye in the middle Arizona and Nevada (Tuskes et al. 1996). of his forehead (Himmelman 2002). The name is because of the large eyespots in the middle of the moth is hind wings. Description The polyphemus moth also has been known by the genus name Telea, but it and the Old World species in the genus Adults Antheraea are not considered to be sufficiently different to The adult wingspan is 10 to 15 cm (approximately 4 to warrant different generic names. Because the name Anther- 6 inches) (Covell 2005). The upper surface of the wings aea has been used more often in the literature, Ferguson is various shades of reddish brown, gray, light brown, or (1972) recommended using that name rather than Telea yellow-brown with transparent eyespots. There is consider- to avoid confusion. Both genus names were published in able variation in color of the wings even in specimens from the same year. For a historical account of the polyphemus the same locality (Holland 1968). The large hind wing moth’s taxonomy see Ferguson (1972) or Tuskes et al. eyespots are ringed with prominent yellow, white (partial), (1996). -

A Melanistic Specimen of Antheraea Polyphemus Polyphemus (Saturniidae)

VOLUME 33, NUMBER 2 147 Robinson trap. Unfortunately the apical regions of both forewings are badly damaged, probably from flying inside the trap. This specimen is at the Peabody Museum, Yale University. The 1972 specimen was confimled by Dr. Franclemont along with the above Givira. Barnes and McDunnough (op. cit. ) record it only from Florida and Kimball's records (op. cit.) cover much of that state. All of these specimens were collected within 20 m to the north of the Batsto Nature Center, situated on the top of the small hill near the east bank of the Batsto river, just above the dam. The surrounding vegetation includes a woodlot of various oaks and adventive species and extensive areas of essentially natural oak-pine and pine-oak forests extending more or less unbroken for hundreds of square kilometers, especially to the north. The pines are Pinus echinata Mill., and P. rigida Mill., with the former predominating at the im mediate area of the captures. DALE F. SCHWEITZER, Curatorial Associate, Entomology, Peabody Museum, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520. Journal of The Lepidopterists' Society 33(2), 1979, 147-148 A MELANISTIC SPECIMEN OF ANTHERAEA POLYPHEMUS POLYPHEMUS (SATURNIIDAE) On 2 June 1975, the senior author received a living specimen of Antheraea poly phemus polyphemus (Cramer) that was most unusual in coloration (Figs. 1-4). The moth, a female, had eclosed on 1 June from a cocoon found approximately two weeks previously on a fence in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The cocoon had been given 4 Figs. 1-4. Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer): l. typical female from Winnipeg, dorsum; 2. -

A New, Unexpected Species of the Genus Antheraea Hübner, 1819 ("1816") from Luzon Island, Philippines (Lepidoptera, Saturniidae) 65-70 Nachr

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nachrichten des Entomologischen Vereins Apollo Jahr/Year: 2008 Band/Volume: 29 Autor(en)/Author(s): Naumann Stefan, Lourens Johannes H. Artikel/Article: A new, unexpected species of the genus Antheraea Hübner, 1819 ("1816") from Luzon Island, Philippines (Lepidoptera, Saturniidae) 65-70 Nachr. entomol. Ver. Apollo, N. F. 29 (/2): 65–70 (2008) 65 A new, unexpected species of the genus Antheraea Hübner, 1819 (“1816”) from Luzon Island, Philippines (Lepidoptera, Saturniidae) Stefan Naumann and Johannes H. Lourens Dr. Stefan Naumann, Hochkirchstrasse 11, D-0829 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] Dr. Johannes H. Lourens, Ridgewood Park, Brgy. Gulang-Gulang, Lucena City 430, Philippines; janhlourens@yahoo.com Abstract: A new species of the genus Antheraea Hübner, A. (A.) halconensis Paukstadt & Brosch, 996 is known 89 (“86”) in the subgenus Antheraea from the Philip- as sole representative of the helferi-group (compare pines is described: A. (A). hagedorni sp. n., male holotype also Lampe et al. 997, Nässig & Treadaway 998, from Luzon Island, will be deposited in the Zoological Museum of the Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany. The Naumann & Nässig 998), this is a first record of a second species can be identified by its elongated forewing apex, the member of the helferi-group syntopically on the same typical more or less light orange ground colour, details of Philippine Island. Similar situations are known for the fore- and hindwing ocellus, and ornamentation of the males, islands of Borneo and Sumatra as well as the Malayan and details in the very small male genitalia structures. -

Parasitism and Suitability of Aprostocetus Brevipedicellus on Chinese Oak Silkworm, Antheraea Pernyi, a Dominant Factitious Host

insects Article Parasitism and Suitability of Aprostocetus brevipedicellus on Chinese Oak Silkworm, Antheraea pernyi, a Dominant Factitious Host Jing Wang 1, Yong-Ming Chen 1, Xiang-Bing Yang 2,* , Rui-E Lv 3, Nicolas Desneux 4 and Lian-Sheng Zang 1,5,* 1 Institute of Biological Control, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun 130118, China; [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (Y.-M.C.) 2 Subtropical Horticultural Research Station, United States Department of America, Agricultural Research Service, Miami, FL 33158, USA 3 Institute of Walnut, Longnan Economic Forest Research Institute, Wudu 746000, China; [email protected] 4 Institut Sophia Agrobiotech, Université Côte d’Azur, INRAE, CNRS, UMR ISA, 06000 Nice, France; [email protected] 5 Key Laboratory of Green Pesticide and Agricultural Bioengineering, Guizhou University, Guiyang 550025, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.-B.Y.); [email protected] (L.-S.Z.) Simple Summary: The egg parasitoid Aprostocetus brevipedicellus Yang and Cao (Eulophidae: Tetrastichi- nae) is one of the most promising biocontrol agents for forest pest control. Mass rearing of A. bre- vipedicellus is critical for large-scale field release programs, but the optimal rearing hosts are currently not documented. In this study, the parasitism of A. brevipedicellus and suitability of their offspring on Antheraea pernyi eggs with five different treatments were tested under laboratory conditions to determine Citation: Wang, J.; Chen, Y.-M.; Yang, the performance and suitability of A. brevipedicellus. Among the host egg treatments, A. brevipedicellus X.-B.; Lv, R.-E.; Desneux, N.; Zang, exhibited optimal parasitism on manually-extracted, unfertilized, and washed (MUW) eggs of A. -

Polyphemus Moth Antheraea Polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W

EENY-531 Polyphemus Moth Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W. Hall2 The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of amateur enthusiasts and also have been used for numerous insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant physiological studies—particularly for studies on molecular to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested mechanisms of sex pheromone action. laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences. Distribution Polyphemus moths are our most widely distributed large Introduction silk moths. They are found from southern Canada down The polyphemus moth, Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer), into Mexico and in all of the lower 48 states, except for is one of our largest and most beautiful silk moths. It is Arizona and Nevada (Tuskes et al. 1996). named after Polyphemus, the giant cyclops from Greek mythology who had a single large, round eye in the middle Description of his forehead (Himmelman 2002). The name is because of the large eyespots in the middle of the moth is hind wings. Adults The polyphemus moth also has been known by the genus The adult wingspan is 10 to 15 cm (approximately 4 to name Telea, but it and the Old World species in the genus 6 inches) (Covell 2005). The upper surface of the wings Antheraea are not considered to be sufficiently different to is various shades of reddish brown, gray, light brown, or warrant different generic names. Because the name Anther- yellow-brown with transparent eyespots. There is consider- aea has been used more often in the literature, Ferguson able variation in color of the wings even in specimens from (1972) recommended using that name rather than Telea the same locality (Holland 1968). -

Redalyc.Distribution and Status of Antheraea Pernyi (Guérin

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Pinya, S.; Suárez-Fernández, J. J.; Canyelles, X. Distribution and status of Antheraea pernyi (Guérin- Méneville, 1855) in the island of Mallorca (Spain) (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 41, núm. 163, septiembre, 2013, pp. 377-381 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45529269014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 377-381 Distribution and status 4/9/13 12:13 Página 377 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 41 (163), septiembre 2013: 377-381 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 Distribution and status of Antheraea pernyi (Guérin- Méneville, 1855) in the island of Mallorca (Spain) (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) S. Pinya, J. J. Suárez-Fernández & X. Canyelles Abstract Antheraea pernyi is one of the few Saturniidae moths present in Europe, which was initially introduced in the XIXth Century for its silk-producing qualities, arriving to the Balearic Islands (Mallorca and Menorca) in 1881. Due to the lack of recent citations, A. pernyi has been considered scarce or even endangered in Mallorca, since the last published citations date back from the 1960’s. Several observations have been recorded during the last few years, indicating that a population of A. pernyi still exists. Our data show that the species is distributed in an area close to 54.000 ha and suggest that A. -

Moth Wings Are Acoustic Metamaterials

Moth wings are acoustic metamaterials Thomas R. Neila,1, Zhiyuan Shena,1, Daniel Roberta, Bruce W. Drinkwaterb, and Marc W. Holderieda,2 aSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TQ, United Kingdom; and bDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TR, United Kingdom Edited by Katia Bertoldi, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Evelyn L. Hu October 4, 2020 (received for review July 10, 2020) Metamaterials assemble multiple subwavelength elements to reduced the mean target strength in both wing regions by −3.51 ± create structures with extraordinary physical properties (1–4). Op- 1.02 and −4.80 ± 0.61 dB in A. pernyi and by −3.03 ± 0.69 tical metamaterials are rare in nature and no natural acoustic and −5.02 ± 1.09 dB in D. lucina. Because only small fractions of metamaterials are known. Here, we reveal that the intricate scale the incident sound are transmitted or diffused (SI Appendix,Figs. layer on moth wings forms a metamaterial ultrasound absorber S1 and S2), this reduction in target strength can be attributed to (peak absorption = 72% of sound intensity at 78 kHz) that is absorption (absorption coefficient α). In contrast, in both butterfly 111 times thinner than the longest absorbed wavelength. Individ- species, the presence of scales increased the mean target strength ual scales act as resonant (5) unit cells that are linked via a shared by 0.53 ± 0.44 and 1.10 ± 0.67 dB on the two wing regions in G. wing membrane to form this metamaterial, and collectively they agamemnon and by 1.56 ± 0.81 and 1.31 ± 0.73 dB in D. -

Edible Insects

1.04cm spine for 208pg on 90g eco paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 171 FORESTRY 171 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 171 Edible insects Edible insects Future prospects for food and feed security Future prospects for food and feed security Edible insects have always been a part of human diets, but in some societies there remains a degree of disdain Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security and disgust for their consumption. Although the majority of consumed insects are gathered in forest habitats, mass-rearing systems are being developed in many countries. Insects offer a significant opportunity to merge traditional knowledge and modern science to improve human food security worldwide. This publication describes the contribution of insects to food security and examines future prospects for raising insects at a commercial scale to improve food and feed production, diversify diets, and support livelihoods in both developing and developed countries. It shows the many traditional and potential new uses of insects for direct human consumption and the opportunities for and constraints to farming them for food and feed. It examines the body of research on issues such as insect nutrition and food safety, the use of insects as animal feed, and the processing and preservation of insects and their products. It highlights the need to develop a regulatory framework to govern the use of insects for food security. And it presents case studies and examples from around the world. Edible insects are a promising alternative to the conventional production of meat, either for direct human consumption or for indirect use as feedstock. -

Common Butterflies and Moths (Order Lepidoptera) in the Wichita Mountains and Surrounding Areas

Common Butterflies and Moths (Order Lepidoptera) in the Wichita Mountains and Surrounding Areas Angel Chiri Less than 2% of known species in the U.S. have Entomologist approved common names. Relying on only common names for individual species may lead Introduction to confusion, since more than one common name may exist for the same species, or the With over 11,000 species described in the U.S. same name may be used for more than one and Canada, butterflies and moths are among the species. Using the scientific name, which is the most common and familiar insects. With few same in any language or region, eliminates this exceptions, the adults have two pairs of wings problem. Furthermore, only scientific names are covered with minute and easily dislodgeable used in the scientific literature. Common names scales. The mouthparts consist of a long, are not capitalized. flexible, and coiled proboscis that is used to absorb nectar. Butterflies and skippers are All photos in this guide were taken by the author diurnal, while most moths are nocturnal. using a Canon PowerShot SX110 IS camera. The Lepidoptera undergo a full metamorphosis. Family Pieridae (sulfurs and whites) The larva has a well developed head, with opposable mandibles designed for chewing and Pierids are common, mostly medium-sized, six simple eyes arranged in a semicircle, on each yellowish or white butterflies. The cloudless side of the head. The first three segments (the sulphur, Phoebis sennae has greenish-yellow or thorax) each bears a pair of segmented legs that lemon yellow wings with a spot resembling a end in a single claw. -

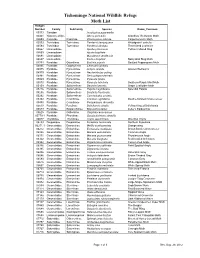

Tishomingo NWR Moth List

Tishomingo National Wildlife Refuge Moth List Hodges Number Family SubFamily Species Name_Common 00373 Tineidae Acrolophus popeanella 02401 Yponomeutidae Atteva punctella Ailanthus Webworm Moth 02693 Cossidae Cossinae Prionoxystus robinae Carpenterworm Moth 03593 Tortricidae Tortricinae Pandemis lamprosana Woodgrain Leafroller 03594 Tortricidae Tortricinae Pandemis limitata Three-lined Leafroller 04667 Limacodidae Apoda y-inversum Yellow-Collared Slug 04669 Limacodidae Apoda biguttata 04691 Limacodidae Monoleuca semifascia 04697 Limacodidae Euclea delphinii Spiny Oak Slug Moth 04794 Pyralidae Odontiinae Eustixia pupula Spotted Peppergrass Moth 04895 Pyralidae Glaphyriinae Chalcoela iphitalis 04975 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Achyra rantalis Garden Webworm 04979 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Neohelvibotys polingi 04991 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Sericoplaga externalis 05069 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Pyrausta tyralis 05070 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Pyrausta laticlavia Southern Purple Mint Moth 05159 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Desmia funeralis Grape Leaffolder Moth 05226 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Palpita magniferalis Splendid Palpita 05256 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Diastictis fracturalis 05292 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Conchylodes ovulalis 05362 Pyralidae Crambinae Crambus agitatellus Double-banded Grass-veneer 05450 Pyralidae Crambinae Parapediasia decorella 05533 Pyralidae Pyralinae Dolichomia olinalis Yellow-fringed Dolichomia 05579 Pyralidae Epipaschiinae Epipaschia zelleri Zeller's Epipaschia 05625 Pyralidae Galleriinae Omphalocera cariosa 05779.1 Pyralidae Phycitinae Quasisalebriaria -

Diverse Evidence That Antheraea Pernyi (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) Is Entirely of Sericultural Origin

VAN DER POORTEN: Immatures of Satyrinae in Sri Lanka PEIGLER: Sericultural origin of A. pernyi TROP. LEPID. RES., 22(2): 93-99, 2012 93 DIVERSE EVIDENCE THAT ANTHERAEA PERNYI (LEPIDOPTERA: SATURNIIDAE) IS ENTIRELY OF SERICULTURAL ORIGIN Richard S. Peigler Department of Biology, University of the Incarnate Word, 4301 Broadway, San Antonio, Texas 78209-6397 U.S.A. email: [email protected] and Research Associate, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera & Biodiversity, Gainesville, Florida 32611, U.S.A. Abstract - There is a preponderance of evidence that the tussah silkmoth Antheraea pernyi was derived thousands of years ago from the wild A. roylei. Historical, sericultural, morphological, cytogenetic, and taxonomic data are cited in support of this hypothesis. This explains why A. pernyi is very easy to mass rear, produces copious quantities of silk in its cocoons, and the oak tasar “hybrid”crosses between A. pernyi and A. roylei reared in India were fully fertile through numerous generations. The case is made that it is critical to conserve populations and habitats of the wild progenitor as a genetic resource for this economically important silkmoth. Key words: China, Chinese oak silkmoth, India, sericulture, temperate tasar silk, tussah silk, wild silk INTRODUCTION THE EVIDENCE Numerous examples are known for which domesticated Cytogenetic, physiological, and molecular evidence. animals or cultivated plants differ dramatically from their wild Studies investigating the cytogenetics of these moths reported ancestral species, and frequently the artificially-selected entity the chromosome numbers for A. roylei to be n=31 and for A. carries a separate scientific name from the one in nature. In some pernyi to be n=49, with n=31 being the modal (ancestral) number cases where the wild and domesticated animals are considered for most saturniids (Belyakova & Lukhtanov 1994, 1996, and to be the same species, and the latter were named first, references cited therein).