Viburnum Lantana L. and Viburnum Opulus L. (V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disease and Insect Resistant Ornamental Plants: Viburnum

nysipm.cornell.edu 2018 hdl.handle.net/1813/56379 Disease and Insect Resistant Ornamental Plants Mary Thurn, Elizabeth Lamb, and Brian Eshenaur New York State Integrated Pest Management Program, Cornell University VIBURNUM Viburnum pixabay.com Viburnum is a genus of about 150 species of de- ciduous, evergreen and semi-evergreen shrubs or small trees. Widely used in landscape plantings, these versatile plants offer diverse foliage, color- ful fruit and attractive flowers. Viburnums are relatively pest-free, but in some parts of the US the viburnum leaf beetle can be a serious pest in both landscape and natural settings. Potential diseases include bacterial leaf spot and powdery mildew. INSECTS Viburnum Leaf Beetle, Pyrrhalta viburni, is a leaf-feeding insect native to Europe and Asia. In North America, the beetle became established around Ottawa, Canada in the 1970’s and was first detected in the United States in Maine in 1994 and in New York in 1996. It has since spread through much of the northeastern US (15). Reports of viburnum leaf beetle in the Midwest include Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois (1) and Washington and British Columbia, Canada in the Pacific Northwest (7). The beetle is host-specific and feeds only on Viburnum, but there are preferences within the genus (6). Species with thick leaves tend to be more resistant and feeding is more likely to occur on plants grown in the shade (17). Feeding by both larvae and adults causes tattered leaves and may result in extensive defoliation – repeated defoliations can kill the plant. Viburnum Leaf Beetle Reference Species/Hybrids Cultivar Moderately Resistant Susceptible Susceptible Viburnum acerifolium 14, 15 Viburnum burkwoodii 14, 15 Viburnum carlesii 14, 15, 16 Viburnum dentatum 2, 6, 14, 15 Viburnum dilatatum 15 Viburnum Leaf Beetle Reference Species/Hybrids Cultivar Moderately Resistant Susceptible Susceptible Viburnum lantana 14, 15 Viburnum lantanoides/alnifolium 14 Viburnum lentago 14, 15 Viburnum macrocephalum 14 Viburnum opulus 2, 6, 14, 15 Viburnum plicatum f. -

THE ERIOPHYID MITES of CALIFORNIA (Acarina: Eriophyidae) by H

BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY VOLUME 2, NO. 1 THE ERIOPHYID MITES OF CALIFORNIA (Acarina: Eriophyidae) BY H. H. KEIFER (California Scare Department of Agriculture) UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1352 BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY Editors: E. 0. Essig, S. B. Freeborn, E. G. Linsley, R. L. Usinger Volume 2, No. 1, pp. 1-128, plates 1-39 Submitted by Editors, May 6, 1952 Issued December 12, 1952 Price $2.00 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES CALIFORNIA CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, ENGLAND PRINTED BY OFFSET IN THE UNITED STATBS OF AMERICA Contents Page Introduction .......................... 1 Hostlist ........................... 5 Keys to Genera. Species. and higher Groups ...........11 Discussion of Species ..................... 20 Bib 1iography .......................... 62 Host index ........................... 64 List of comn names ...................... 67 Index to mites. Genera. Species. etc .............. 08 Plate symbols ......................... 71 List of plates ......................... 72 Plates ............................. 74 THE ERIOPHYID MITES OF CALIFORNIA Introduction ’IhisBulletin is the result of fifteen years would classify these mites at the present, faces of intermittent exploration of California for the prospect of a growing number of species in the Friophyid mites. hhen the work began in 1937 the large genera, and of broad revisions to come. But principal species recognized were the relatively I believe the average type of Eriophyid to have al- few economic species. ‘Ihis situation not only left ready been pretty well defined, since these mites an opportunity to discover and describe new spe- are widespread, and ancient in origin. cies, it also demanded that as many new Eriophyids As we now know these tiny creatures, they con- as possible be put in print in order to erect a stitute a closed group, structurally pointing to taxonomic framework. -

The Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Botanical Garden in Lublin As a Refuge of the Moths (Lepidoptera: Heterocera) Within the City

Acta Biologica 23/2016 | www.wnus.edu.pl/ab | DOI: 10.18276/ab.2016.23-02 | strony 15–34 The Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Botanical Garden in Lublin as a refuge of the moths (Lepidoptera: Heterocera) within the city Łukasz Dawidowicz,1 Halina Kucharczyk2 Department of Zoology, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Akademicka 19, 20-033 Lublin, Poland 1 e-mail: [email protected] 2 e-mail: [email protected] Keywords biodiversity, urban fauna, faunistics, city, species composition, rare species, conservation Abstract In 2012 and 2013, 418 species of moths at total were recorded in the Botanical Garden of the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin. The list comprises 116 species of Noctuidae (26.4% of the Polish fauna), 116 species of Geometridae (28.4% of the Polish fauna) and 63 species of other Macrolepidoptera representatives (27.9% of the Polish fauna). The remaining 123 species were represented by Microlepidoptera. Nearly 10% of the species were associated with wetland habitats, what constitutes a surprisingly large proportion in such an urbanised area. Comparing the obtained data with previous studies concerning Polish urban fauna of Lepidoptera, the moths assemblages in the Botanical Garden were the most similar to the one from the Natolin Forest Reserve which protects the legacy of Mazovian forests. Several recorded moths appertain to locally and rarely encountered species, as Stegania cararia, Melanthia procellata, Pasiphila chloerata, Eupithecia haworthiata, Horisme corticata, Xylomoia graminea, Polychrysia moneta. In the light of the conducted studies, the Botanical Garden in Lublin stands out as quite high biodiversity and can be regarded as a refuge for moths within the urban limits of Lublin. -

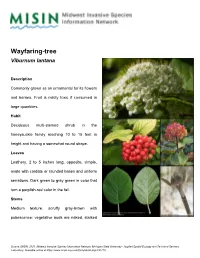

Wayfaring-Tree Viburnum Lantana

Wayfaring-tree Viburnum lantana Description Commonly grown as an ornamental for its flowers and berries. Fruit is mildly toxic if consumed in large quantities. Habit Deciduous multi-stemed shrub in the honeysuckle family reaching 10 to 15 feet in height and having a somewhat round shape. Leaves Leathery, 2 to 5 inches long, opposite, simple, ovate with cordate or rounded bases and uniform serrations. Dark green to gray green in color that turn a purplish-red color in the fall. Stems Medium texture, scruffy gray-brown with pubescence; vegetative buds are naked, stalked Source: MISIN. 2021. Midwest Invasive Species Information Network. Michigan State University - Applied Spatial Ecology and Technical Services Laboratory. Available online at https://www.misin.msu.edu/facts/detail.php?id=270. and scruffy gray-brown. Bark is initially smooth and gray-brown and lenticelled, becoming somewhat scaly. Flowers Showy, displayed in 3 to 5 inchese flat-top dense clusters of tiny creamy white flowers, each with 5 petals and bloom in mid-May. Tend to have an unpleasant fishy odor. Fruits and Seeds Elliptical berries form in drupes/clusters. Each are 1/3 inch long, somewhat flattened, green to red and finally black in color. Habitat Native to Europe and western Asia. Grows in full sun to partial shade with fertile, well-drained, loamy soils. It can tolerate calcareous and dry soils. Reproduction Vegetatively or by seeds. Roots are fibrous. Similar Linden arrowwood (Viburnum dilatatum), Leatherleaf arrowwood (Viburnum rhytidophyllum), Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides), Koreanspice viburnum (Viburnum carlesii). Monitoring and Rapid Response Girdling by removing bark and phloem layer from 10 cm band around trunk; cut stems with shears, Source: MISIN. -

Die Pflanzenwespen

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mitteilungen der Abteilung für Zoologie am Landesmuseum Joanneum Graz Jahr/Year: 1987 Band/Volume: 40_1987 Autor(en)/Author(s): Schedl Wolfgang Artikel/Article: Die Pflanzenwespen (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) des Landesmuseums Joanneum in Graz Teil 6: Tenthredinoidea: Familie Tenthredinidae, Unterfamilie Tenthredininae 1-23 ©Landesmuseum Joanneum Graz, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mitt. Abt. Zool. Landesmus. Joanneum Heft 40 S. 1—23 Graz 1987 Aus dem Institut für Zoologie der Universität Innsbruck Abteilung für Terrestrische Ökologie und Taxonomie Die Pflanzenwespen (Hymenoptera, Sym- phyta) des Landesmuseums Joanneum in Graz Teil 6: Tenthredinoidea: Familie Tenthredinidae, Unter- familie Tenthredininae Von Wolfgang SCHEDL Eingelangt am 14. April 1986 Mit 4 Abbildungen Inhalt: Es handelt sich um Ergebnisse der weiteren Bearbeitung von Pflanzenwespen des Landesmuseums Joanneum durch den Verf., speziell der Unterfamilie Tenthredininae innerhalb der Blattwespen i. e. S. Dabei wurden 502 Exemplare 72 Spezies und 3 Subspezies aus 10 Genera zugeordnet. Besonders bemerkenswert für die Fauna Österreichs sind die Taxone Tenthredo bifasciata violacea (ANDRÉ), T. neobesa ZOMBORI, T. succincta LEP. sensu CHEVIN 1983 und Macrophya alboannulata COSTA, sind neu für Österreich. Unter den behandelten Exemplaren befinden sich auch solche aus Deutschland (BRD und DDR), Italien, Jugoslawien und Ungarn. Abstract: Results of the further study of sawflies s. str. of the Landesmuseum Joanneum by the author. 502 specimens were studied and determined all of the subfamily Tenthredininae belonging to 10 genera, 72 species and 3 subspecies. Of special interest for the Austrian fauna are Tenthredo bif asciata violacea (ANDRÉ), T. neobesa ZOMBORI, T. -

Elderberry (Pdf)

f BWSR Featured Plant Name : American Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis L.) Plant Family: Adoxaceae (Moschatel) American Elderberry is a shrub that is Statewide Wetland both beautiful and functional. Its showy Indicator Status: white flowers develop into black berries FACW that are used by a wide variety of birds and mammals. Carpenter and mason bees also use its stems for nesting and it provides pollen for a wide variety native bees, flies and beetles. Its ability to form dense stands in riparian areas makes it well suited to buffer planting and other The flat-topped shape of the flower head soil stabilization projects. is very distinctive photo by Dave Hanson The leaves are long and lace- Identification like in shape Photo by Dave This thicket-forming shrub can be identified by its unique flowers and berries. The Hanson stems are tall, erect, and arching. The newest branches are green in color and glabrous. Older branches are grayish-brown, and have warty-like lenticels. With age the branches become rougher. The leaves are pinnately compound and deciduous with elliptical or lance-like leaflets. Leaflet surfaces are dark green, slightly hairy, and have finely serrated margins. Bases of the leaves are rounded, while the tips abruptly come to a point. The stalks of the leaflets are green with a hairy channel running up the stalk. Numerous flat-topped flower heads appear and bloom from late June to early August. Flowers are white and have a very distinctive odor. The fruit, which is a round berry, ripens from July to August. Although the purple-black fruit is edible, it is slightly bitter. -

A Contribution to the Knowledge of the Tenthredinidae (Symphyta, Hymenoptera)

TurkJZool 28(2004)37-54 ©TÜB‹TAK AContributiontotheKnowledgeoftheTenthredinidae (Symphyta,Hymenoptera)FaunaofTurkey PartI:TheSubfamilyTenthredininae* ÖnderÇALMAfiUR,HikmetÖZBEK AtatürkUniversity,FacultyofAgriculture,DepartmentofPlantProtection, 25240Erzurum-TURKEY Received:07.02.2003 Abstract: ThesubfamilyTenthredininaeinthefamilyTenthredinidaewastreatedinthispartofthestudyregardingthesawfly (Symphyta,Hymenoptera)faunaofTurkey.Thematerialswerecollectedfromvariouslocalitiesaroundthecountry,though examplesfromeasternTurkeyarepredominant.Afterexaminingmorethan2500specimens,57speciesin8generawererecorded. ElevenspecieswerenewforTurkishfauna;ofthese3specieswererecordedforthefirsttimeasAsianfauna.Furthermore,3 specieswereendemicforTurkey.ThedistributionandnewareasaswellasthehostplantsofsomespeciesaroundTurkeyandth e worldweregiven.Foreachspeciesitschorotypewasreported. KeyWords: Hymenoptera,Tenthredinidae,Tenthredininae,Fauna,Turkey Türkiye’ninTenthredinidae(Symphyta,Hymenoptera)Faunas›naKatk›lar Bölüm:ITenthredininaeAltfamilyas› Özet: Türkiye’nintestereliar›(Symphyta,Hymenoptera)faunas›n›ntespitineyönelikçal›flmalar›nbubölümünde;Tenthredininae (Tenthredinidae)altfamilyas›eleal›nm›fl;incelenen2500’denfazlaörneksonucu,sekizcinseba¤l›toplam57türsaptanm›flt›r. Türkiyefaunas›içinyeniolduklar›saptanan11türdenüçününAsyafaunas›içindeyenikay›tolduklar›belirlenmifltir.ÜçtürünTürkiye içinendemikolduklar›saptanm›flt›r.Tespitedilentürlerinhementamam›içinyeniyay›lmaalanlar›belirlenmifl,birço¤unun konukçular›bulunmufltur.Türkiyevedünyadakida¤›l›fllar›chorotype’leriilebirlikteverilmifltir. -

Phylogeny and Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Dipsacales, with Special Reference to Sinadoxa and Tetradoxa (Adoxaceae)

PHYLOGENY AND PHYLOGENETIC TAXONOMY OF DIPSACALES, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SINADOXA AND TETRADOXA (ADOXACEAE) MICHAEL J. DONOGHUE,1 TORSTEN ERIKSSON,2 PATRICK A. REEVES,3 AND RICHARD G. OLMSTEAD 3 Abstract. To further clarify phylogenetic relationships within Dipsacales,we analyzed new and previously pub- lished rbcL sequences, alone and in combination with morphological data. We also examined relationships within Adoxaceae using rbcL and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences. We conclude from these analyses that Dipsacales comprise two major lineages:Adoxaceae and Caprifoliaceae (sensu Judd et al.,1994), which both contain elements of traditional Caprifoliaceae.Within Adoxaceae, the following relation- ships are strongly supported: (Viburnum (Sambucus (Sinadoxa (Tetradoxa, Adoxa)))). Combined analyses of C ap ri foliaceae yield the fo l l ow i n g : ( C ap ri folieae (Diervilleae (Linnaeeae (Morinaceae (Dipsacaceae (Triplostegia,Valerianaceae)))))). On the basis of these results we provide phylogenetic definitions for the names of several major clades. Within Adoxaceae, Adoxina refers to the clade including Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa, and Adoxa.This lineage is marked by herbaceous habit, reduction in the number of perianth parts,nectaries of mul- ticellular hairs on the perianth,and bifid stamens. The clade including Morinaceae,Valerianaceae, Triplostegia, and Dipsacaceae is here named Valerina. Probable synapomorphies include herbaceousness,presence of an epi- calyx (lost or modified in Valerianaceae), reduced endosperm,and distinctive chemistry, including production of monoterpenoids. The clade containing Valerina plus Linnaeeae we name Linnina. This lineage is distinguished by reduction to four (or fewer) stamens, by abortion of two of the three carpels,and possibly by supernumerary inflorescences bracts. Keywords: Adoxaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Dipsacales, ITS, morphological characters, phylogeny, phylogenetic taxonomy, phylogenetic nomenclature, rbcL, Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa. -

Contribution À L'inventaire Des Hyménoptères Symphytes Du

Bulletin de la Société entomologique de France, 120 (4), 2015 : 473-484. Contribution à l’inventaire des Hyménoptères Symphytes du département du Morbihan par Henri CHEVIN1, Henri SAVINA2 & Mael GARRIN3 1 17 rue des Marguerites, F – 78330 Fontenay-le-Fleury 2 Parc Majorelle, 33 chemin du Ramelet-Moundi, bât. C, app. 16, F – 31100 Toulouse <[email protected]> 3 Kervranig, F – 56480 Sainte-Brigitte Résumé. – Établi à partir de récoltes échelonnées de 1973 à 2014, l’inventaire des Hyménoptères Symphytes du dépar tement du Morbihan s’élève à 193 espèces. Pour chacune d’elles sont indiqués la ou les plantes-hôtes connues, le nombre et le sexe des individus, les localités, les dates ou périodes de récolte. Dans cet inventaire, 12 espèces sont réputées très rares pour la France : Xyela julii, Pamphilius sylvarum, Urocerus augur, Arge dimidiata, Heptamelus ochroleucus, Strongylogaster macula, Hoplocampa testudinea, Dineura virididorsata, Pristiphora abbreviata, P. confusa, P. fausta et P. testacea. Abstract. – Contribution to the knowledge of Hymenoptera Symphyta from Morbihan (France). Based on specimens collected from 1973 to 2014, the list of Hymenoptera Symphyta from Morbihan includes 193 species. It provides, for each species, the known host plants, the number and sex of specimens, the localities and the dates or periods of collection. In this list, 12 species are very rarely collected in France: Xyela julii, Pamphilius sylvarum, Urocerus augur, Arge dimidiata, Heptamelus ochroleucus, Strongylogaster macula, Hoplocampa testudinea, Dineura virididorsata, Pristiphora abbreviata, P. confusa, P. fausta et P. testacea. Keywords. – Hymenoptera, Symphyta, faunistics, France, Morbihan. _________________ Un programme de recherches menées par l’INRA de Rennes de 1973 à 1975 et portant sur l’arasement des talus, a conduit le premier auteur à identifier les Hyménoptères Symphytes cap- turés à l’aide de pièges jaunes. -

Viburnum Opulus Var. Americanum

Viburnum opulus L. var. americanum (Mill.) Ait. (American cranberrybush): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project May 8, 2006 James E. Nellessen Taschek Environmental Consulting 8901 Adams St. NE Ste D Albuquerque, NM 87113-2701 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Nellessen, J.E. (2006, May 8). Viburnum opulus L. var. americanum (Mill.) Ait. (American cranberrybush): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/viburnumopulusvaramericanum.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Production of this assessment would not have been possible without the help of others. I wish to thank David Wunker for his help conducting Internet searches for information on Viburnum opulus var. americanum. I wish to thank Dr. Ron Hartman for supplying photocopies of herbarium specimen labels from the University of Wyoming Rocky Mountain Herbarium. Numerous other specimen labels were obtained through searches of on-line databases, so thanks go to those universities, botanic gardens, and agencies (cited in this document) for having such convenient systems established. I would like to thank local Region 2 botanists Bonnie Heidel of the Wyoming Natural Heritage Program, and Katherine Zacharkevics and Beth Burkhart of the Black Hills National Forest for supplying information. Thanks go to Paula Nellessen for proofing the draft of this document. Thanks go to Teresa Hurt and John Taschek of Taschek Environmental Consulting for supplying tips on style and presentation for this document. Thanks are extended to employees of the USDA Forest Service Region 2, Kathy Roche and Richard Vacirca, for reviewing, supplying guidance, and making suggestions for assembling this assessment. -

Eriophyoid Mite Fauna (Acari: Trombidiformes: Eriophyoidea) of Turkey: New Species, New Distribution Reports and an Updated Catalogue

Zootaxa 3991 (1): 001–063 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3991.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:AA47708E-6E3E-41D5-9DC3-E9D77EAB9C9E ZOOTAXA 3991 Eriophyoid mite fauna (Acari: Trombidiformes: Eriophyoidea) of Turkey: new species, new distribution reports and an updated catalogue EVSEL DENIZHAN1, ROSITA MONFREDA2, ENRICO DE LILLO2,4 & SULTAN ÇOBANOĞLU3 1Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Yüzüncü Yıl, Van, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Soil, Plant and Food Sciences (Di.S.S.P.A.), section of Entomology and Zoology, University of Bari Aldo Moro, via Amendola, 165/A, I–70126 Bari, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 3Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Ankara, Dıskapı, 06110 Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by D. Knihinicki: 21 May 2015; published: 29 Jul. 2015 EVSEL DENIZHAN, ROSITA MONFREDA, ENRICO DE LILLO & SULTAN ÇOBANOĞLU Eriophyoid mite fauna (Acari: Trombidiformes: Eriophyoidea) of Turkey: new species, new distribution reports and an updated catalogue (Zootaxa 3991) 63 pp.; 30 cm. 29 Jul. 2015 ISBN 978-1-77557-751-5 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-752-2 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2015 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2015 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. -

The Vascular Flora of Rarău Massif (Eastern Carpathians, Romania). Note Ii

Memoirs of the Scientific Sections of the Romanian Academy Tome XXXVI, 2013 BIOLOGY THE VASCULAR FLORA OF RARĂU MASSIF (EASTERN CARPATHIANS, ROMANIA). NOTE II ADRIAN OPREA1 and CULIŢĂ SÎRBU2 1 “Anastasie Fătu” Botanical Garden, Str. Dumbrava Roşie, nr. 7-9, 700522–Iaşi, Romania 2 University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Iaşi, Faculty of Agriculture, Str. Mihail Sadoveanu, nr. 3, 700490–Iaşi, Romania Corresponding author: [email protected] This second part of the paper about the vascular flora of Rarău Massif listed approximately half of the whole number of the species registered by the authors in their field trips or already included in literature on the same area. Other taxa have been added to the initial list of plants, so that, the total number of taxa registered by the authors in Rarău Massif amount to 1443 taxa (1133 species and 310 subspecies, varieties and forms). There was signaled out the alien taxa on the surveyed area (18 species) and those dubious presence of some taxa for the same area (17 species). Also, there were listed all the vascular plants, protected by various laws or regulations, both internal or international, existing in Rarău (i.e. 189 taxa). Finally, there has been assessed the degree of wild flora conservation, using several indicators introduced in literature by Nowak, as they are: conservation indicator (C), threat conservation indicator) (CK), sozophytisation indicator (W), and conservation effectiveness indicator (E). Key words: Vascular flora, Rarău Massif, Romania, conservation indicators. 1. INTRODUCTION A comprehensive analysis of Rarău flora, in terms of plant diversity, taxonomic structure, biological, ecological and phytogeographic characteristics, as well as in terms of the richness in endemics, relict or threatened plant species was published in our previous note (see Oprea & Sîrbu 2012).