J&J History Book.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Haag Reflections

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design ___________________________________ RICHARD HAAG ORAL HISTORY REFLECTIONS ___________________________________ Charles Anderson Lucia Pirzio-Biroli/ Michele Marquardi Luca Maria Francesco Fabris Falken Forshaw Gary R. Hilderbrand Jeffrey Hou Linda Jewell Grant Jones Douglas Kelbaugh Reuben Rainey Nancy D. Rottle Allan W. Shearer Peter Steinbrueck Michael Van Valkenburgh Thaisa Way © 2014 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. Reflections of Richard Haag by Charles Anderson May 2014 I first worked with Rich in the 1990's. I heard a ton of amazing stories during that time and we worked on several great projects but he didn't see the need for me to use a computer. That was the reason I left his office. Years later he invited me to work with him on the 2008 Beijing Olympic competition. In the design charrettes he and I did numerous drawings but I did much of my work on a tablet computer. In consequent years we met for lunch and I showed him my projects on an iPad. For the first time I saw a glint in his eye towards that profane technology. I arranged for an iPad to arrive in his office on Christmas Eve in 2012. Cheryl, his wife, made sure Rich was in the office that day to receive it. His name was engraved on it along with the quote, "The cosmos is an experiment", a phrase he authored while I worked for him. He called © 2014 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. -

Day 1, Friday November 10, 2017

Seattle Sample Itinerary Day 1, Friday November 10, 2017 1: Rest up at the Ace Hotel Seattle (Lodging) Address: 2423 1st Ave, Seattle, WA 98121, USA About: Opening hours Sunday: Open 24 hours Monday: Open 24 hours Tuesday: Open 24 hours Wednesday: Open 24 hours Thursday: Open 24 hours Friday: Open 24 hours Saturday: Open 24 hours Phone number: +1 206-448-4721 Website: http://www.acehotel.com/seattle Reviews http://www.yelp.com/biz/ace-hotel-seattle-seattle http://www.tripadvisor.com/Hotel_Review-g60878-d100509-Reviews-Ace_Hotel-Seattle_Washington.html 2: Modern European bistro brunch at Tilikum Place Cafe (Restaurant) Address: 407 Cedar St, Seattle, WA 98121, USA About: We recommend reserving a table in advance at Tilikum, a popular brunch spot serving creative, seasonal breakfast items. Start with the fritters with maple bourbon sauce, then transition to the house-made baked beans and Dutch babies (a fluffy pancake-like treat with a crispy outside and a doughy middle). Finally, wash it all down with a pot of French press coffee and a spicy Bloody Mary. With tall ceilings and massive windows, this airy space is a must-visit for their chic environment and tasty breakfast food. Opening hours Sunday 8AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Monday 11AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Tuesday 11AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Wednesday 11AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Thursday 11AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Friday 11AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Saturday 8AM-3PM, 5PM-10PM Phone number: +1 206-282-4830 Website: http://www.tilikumplacecafe.com/ Reviews https://www.yelp.com/biz/tilikum-place-cafe-seattle-3 http://www.tripadvisor.com/Restaurant_Review-g60878-d1516303-Reviews-Tilikum_Place_Cafe- Seattle_Washington.html 3: See the incredible glass sculptures at Chihuly Garden and Glass (Activity) Address: 305 Harrison St, Seattle, WA 98109, United States About: Featuring the studio works of Dale Chihuly, this is the top attraction in Seattle. -

Bloedel Reserve | February 2012

RICHARD HAAG | BLOEDEL RESERVE | FEBRUARY 2012 Bibliography (partial) Ament, Deloris Tarzan. “The Great Escape: Bainbridge Island’s Bloedel Reserve Offers a Tranquil, Green Retreat to Soothe the Spirit.” Seattle Times (9 October 1988) K1, K5. American Academy in Rome, “Annual Exhibition 1998,” June 12-July 12, 1998 (exhibition catalog), 52-55, 106. Appleton, Jay. The Experience of Landscape. Rev. ed. London: John Wiley and Sons, 1996: 248, 250, 254. Arbor Fund, Foundation. Bloedel Reserve. 2010. http://www.bloedelreserve. Beason, Tyrone. “Paul Hayden Kirk Left His Mark On Architecture Of Northwest.” The Seattle Times, May 25, 1995. “Bloedel Reserve: Jury Comments,” [ASLA President’s Award of Design Excellence] (Architectural League of New York’s Inhabited Landscapes exhibition), Places 4:4 (1987): 14-15. Botta, Marina. “Seattle: 140 Acres of Green Rooms.” Abitare (Italy) 272 (March 1989): 219-23. Fabris, Luca M.F. La Natura Come Amante/Nature as a Lover. Maggioli S.p.A. 2010: 7, 9, 13, 70-93. Frankel, Felice (photographs) and Jory Johnson (text). “The Bloedel Reserve.” Modern Landscape Architecture: Redefining the Garden. New York: Abbeville Press, 1991, 52- 69. Frey, Susan Rademacher, “A Series of Gardens,” Landscape Architecture Magazine (September 1986): cover, 55-61, 128. [ASLA President’s Award of Design Excellence coverage and site impressions.] Haag, Richard. “Contemplations of Japanese Influence on the Bloedel Reserve.” Washington Park Arboretum Bulletin 53:2 (Summer 1990): 16-19. Haddad, Laura. “Richard Haag: Bloedel Reserve and Gas Works Park.” Book Review. Arcade, 16.3 (Spring 1998) 34. Illman, Deborah. 1998 UW Showcase: Arts and Humanities at the University of Washington. -

2010 Awards Summary Kristen Lundquist, Jay Curcio, and Linda Pak

2010 WASLA PROFESSIONAL AWARDS AWARDS SUMMARY CO N T E N T S 2ASLA 0 1 0 W P ROFESSIONAL AWARDS S UMMARY INTRODUCTION RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION Message from the President ������������������������������ 2 Functional Landscapes—Assessing Elements of Seattle’s Green Factor ������������������ 16 Award Categories & Descriptions ���������������������� 2 2010 Jurors ��������������������������������������������������������� 3 WORKS IN PROGRESS Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial—Phase II �������������������������� 18 HONOR AWARDS GENERAL DESIGN SPECIAL MENTION Madrona Woods Restoration ����������������������������� 4 GENERAL DESIGN Mercer Slough Environmental Education Center ������������������������������������������������ 6 Cesar Chavez Park ��������������������������������������������� 20 Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel ����������� 8 North End Parks ������������������������������������������������ 21 Pierce County Central Maintenance Facility ��� 22 MERIT AWARDS PLANNING AND ANALYSIS Integrating Habitats Competition: GENERAL DESIGN Growing Together ������������������������������������������� 23 Ella Bailey Park �������������������������������������������������� 10 Seattle Pedestrian Master Plan ������������������������ 24 Taylor 28 ������������������������������������������������������������ 12 West Capitol Campus Historic Landscape Preservation Master Plan ��������������� 25 PLANNING AND ANALYSIS East Redmond Corridor ������������������������������������ 14 COVER PHOTO CREDITS: (TOP LEFT) SVR DESIGN COMPANY; (LOWER -

RETAIL for LEASE 2301 6Th Avenue | Seattle

RETAIL FOR LEASE 2301 6th Avenue | Seattle For more information please contact: GIBRALTAR INVESTMENT PROPERTY SOLUTIONS Laura Miller Ananda Gellock 206.367.6080 | OFFICE (206) 351.3573 | MOBILE (206) 707.3259 | MOBILE 206.367.6087 | FAX [email protected] [email protected] www.gibraltarusa.com Retail FOR LEASE Insignia 2301 6th Avenue Project Overview A signature development by renowned developer, Nat Bosa, Insignia represents the merging of modern architecture, sophisticated style and unprecedented amenities, all coming togeth- er in the city’s most central location. When completed, Insignia will expanse an entire city block and include 26,000 square feet of street level retail space as well as two 41-story residential towers with 707 luxury condo units. Located on the site bounded by 5th Avenue, Battery Street, 6th Avenue and Bell Street in Seattle’s Belltown neighborhood, Insignia has a targeted LEED Silver sustainable design. The project is located two blocks north of the much anticipated Amazon campus, a three block development comprising 3.3 million square feet of office space. Currently under construction, Insignia will be completed in two phases, with an anticipated completion date for the initial phase of July 2015. Project Details Phase 1 (South): ................................... 11,114 square feet (total) Unit #1S: ................................... 2,223 square feet Unit #2S: ................................... 2,155 square feet Unit #3S: ................................... 3,799 square feet Unit #3S(A).................................. LEASED! US BANK Phase 2 (North): .................................... 14,363 square feet (total) . ASKING RENT: ....................................... $32 - $36 PSF + NNN TENANT IMPROVEMENTS: ..................... Negotiable PROJECT COMPLETION: ......................... Phase 1: July 2015; Phase 2: June 2016 Phase 2: July 2016 This information has been obtained from sources believed reliable. -

Landmark NOMINATION Application Name: Year Built: 1965-67 (Phase O

Landmark NOMINATION Application Name: Year Built: 1965-67 (Phase One); 1970-71 (Phase Two) (Common, present or historic) Historic – Battelle Memorial Institute Seattle Research Center Present – Talaris Conference Center Street and Number: 4000 NE 41st Street, Seattle, Washington 98105 Assessor’s File No. 1525049010 ________________________________ Legal Description: See attached _________________________________ Plat Name: Town of Yesler Block: n/a Lot: Government Lot 2 Present Owner: 4000 Property, LLC. Present Use: Conference Center Address: 4000 NE 41st Street , Seattle, WA 98105 __________________ Original Owner: Battelle Memorial Institute (BMI) ___________________ Original Use: Research/Institutional Campus __________________________ Architect: NBBJ, Inc.; Rich Haag Associates, Landscape Architect _____ Builder: Farwest Construction Company Description: Present and original (if known) physical appearance and characteristics See attached Landmark Nomination Report Statement of significance: See attached Landmark Nomination Report Photographs: See attached Landmark Nomination Report for graphics—maps, plans and photographs Submitted by: Friends of Battelle/Talaris, contact: Janice Sutter Phone 206.683.9280 Address 4616 25th Ave NE, #146, Seattle, WA 98105 Date March 28, 2013 (revised August 5, 2013) Reviewed Date Historic Preservation Officer Legal Description for Battelle Memorial Institute/Talaris (attachment to Landmark Nomination Application Form) That portion of Government Lot 2 and of the Northeast Quarter of the Northwest Quarter -

Comprehensive List of Seattle Parks Bonus Feature for Discovering Seattle Parks: a Local’S Guide by Linnea Westerlind

COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF SEATTLE PARKS BONUS FEATURE FOR DISCOVERING SEATTLE PARKS: A LOCAL’S GUIDE BY LINNEA WESTERLIND Over the course of writing Discovering Seattle Parks, I visited every park in Seattle. While my guidebook describes the best 100 or so parks in the city (in bold below), this bonus feature lists all the parks in the city that are publicly owned, accessible, and worth a visit. Each park listing includes its address and top features. I skipped parks that are inaccessible (some of the city’s greenspaces have no paths or access points) and ones that are simply not worth a visit (just a square of grass in a median). This compilation also includes the best of the 149 waterfront street ends managed by the Seattle Department of Transportation that have been developed into mini parks. I did not include the more than 80 community P-Patches that are managed by the Department of Neighbor- hoods, although many are worth a visit to check out interesting garden art and peek at (but don’t touch) the garden beds bursting with veggies, herbs, and flowers. For more details, links to maps, and photos of all these parks, visit www.yearofseattleparks.com. Have fun exploring! DOWNTOWN SEATTLE & THE Kobe Terrace. 650 S. Main St. Paths, Seattle Center. 305 Harrison St. INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT city views, benches. Lawns, water feature, cultural institutions. Bell Street Park. Bell St. and 1st Ave. Lake Union Park. 860 Terry Ave. N. to Bell St. and 5th Ave. Pedestrian Waterfront, spray park, water views, Tilikum Place. 2701 5th Ave. -

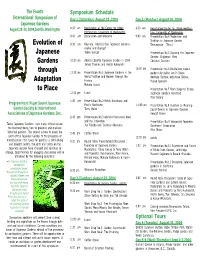

Evolution of Japanese Gardens Through Adaptation to Place

The Fourth Symposium Schedule International Symposium of Day 1.(Saturday) August 28 ,2004 Day 3.(Monday) August 30 ,2004 Japanese Gardens August 28-30, 2004,Seattle, Washington 8:30 am Registration at the Center for Urban 8:30 am Registration:Center for Urban Horticul- Horticulture, University of Washington ture, University of Washington 9:00 am Declaration and Welcome 9:00 am Presentation No.4 Modernism and Tradition in Japanese Garden Evolution of 9:30 am Keynote Address:Can Japanese Gardens Tatsunosuke Tatsui evolve and change? Japanese Takeo Uesugi Presentation No.5 Evolving the Japanese Garden: Shigemori Mirei 10:30 am Address:Seattle Japanese Garden in 2004 Christian Tschumi Gardens James Thomas and Koichi Kobayashi 10:00 am Presentation No.6 Revitalized classic through 11:15 am Presentation No.1:Japanese Gardens in the gardens for public use in Tokyo World:Tradition and Modern through the Noritaka Tashiro, Katsutoyo Shiina, Adaptation History Masao Igarashi Makoto Suzuki to Place Presentation No.7 From Daigo to Ithaca: 12:15 pm Lunch Japanese Gardens Revisited Marc Keane 1:45 pm Presentation No.2:Welch Sanctuary and Program Host: Puget Sound Japanese Pacific Northwest 11:00 am Presentation No.8 Function as Meaning- Garden Society & International Terry Welch Social Events in Japanese Gardens Associations of Japanese Gardens, Inc. Kendall Brown 2:45 pm Presentation No.3:World . of Kuniyoshi Araki and His Innovation Presentation No.9 Vancouver Japanese Today Japanese Gardens face many critical issues: Jun Takeda and Tsutomu Akamatsu -

LAKE UNION Historical WALKING TOUR

B HistoryLink.org Lake Union Walking Tour | Page 1 b Introduction: Lake Union the level of Lake Union. Two years later the waters of Salmon Bay were raised behind the his is a Cybertour of Seattle’s historic Chittenden Locks to the level of Lake Union. South Lake Union neighborhood, includ- Historical T As the Lake Washington Ship Canal’s ing the Cascade neighborhood and portions Walking tour Government Locks (now Hiram of the Denny Regrade. It was written Chittenden Locks) neared its 1917 and curated by Paula Becker with completion, the shores of Lake Union the assistance of Walt Crowley and sprouted dozens of boat yards. For Paul Dorpat. Map by Marie McCaffrey. most of the remaining years of the Preparation of this feature was under- twentieth century, Lake Union was written by Vulcan Inc., a Paul G. Allen one of the top wooden-boat building Company. This Cybertour begins at centers in the world, utilizing rot- Lake Union Park, then loosely follows resistant local Douglas fir for framing the course of the Westlake Streetcar, and Western Red Cedar for planking. with forays into the Cascade neighbor- During and after World War I, a hood and into the Seattle Center area. fleet of wooden vessels built locally for the war but never used was moored Seattle’s in the center of Lake Union. Before “Little Lake” completion of the George Washington ake Union is located just north of the Washington, Salmon Bay, and Puget Sound. Memorial Bridge (called Aurora Bridge) in L geographic center and downtown core A little more than six decades later, Mercer’s 1932, a number of tall-masted ships moored of the city of Seattle. -

Master Plan Design Guidelines: Signage

Century 21 Signage Guidelines Century 21 Signage Guidelines Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................1 Process and Timeline .................................................................1 Existing Sign Locations ......................................................... 2-3 Proposed Sign Locations - Early Implementation Plan .......4-5 Proposed Sign Locations - Century 21 Plan ........................ 6-7 Sign System - Perimeter Campus Signage ...............................8 Sign System - Internal Signage .................................................9 Sign System - Other Signage ...................................................10 Guidelines and Policies ............................................................12 Century 21 Design Guidelines INTRODUCTION The primary objective of the Seattle Center Campus Signage Plan is to establish a logical and legible system of signs that informs and directs visitors, identifi es key sites of interest, and serves to enhance the aesthetic and experiential qualities of the site. This comprehensive plan addresses the existing site as well as phased implementation of new signage over the next 20 years to align with the vision of the Century 21 Master Plan. Seattle Center has a wide spectrum of architecture and open spaces, large and small, loud and quiet, and everything in between. Signage is one of several design elements that can visually unify the site and create greater consistency within the environment. Decongesting and de-cluttering the site by removing outdated signage will help deliver a simpler, cleaner, and greener message about the campus. We can create a more welcoming campus and make the edges and entrances of the site more porous by providing event information at key locations and in creative ways at campus entries and around the perimeter. The signage system will be a key contributor to promoting the brand, contributing to a sense of safety and security, and enhancing the experience of visiting Seattle Center. -

Elliott Avenue Denny Way

Roy St 99 To Woodland Park Zoo Mercer St TM Minor Ave N 9th Ave N Westlake Ave N Dexter Ave N 8th Ave N Boren Ave N Fairview Ave N Terry Ave N 1st Ave N W Republican St SEATTLE Republican St CENTER Aurora Ave N W Harrison St Experience Harrison St 5th Ave N Taylor Ave N Music Project 6th Ave N W Thomas St Thomas St Queen Anne 2nd Ave N John St Ave N John St Space Needle Elliott Avenue Denny Way Terry Ave Minor Ave Broadway Ave Tilikum Place 8th Ave 9th Ave 7th Ave Broad St 6th Ave Clay St OLYMPIC Cedar St 5th Ave SCULPTURE Howell St Vine St Bus PARK Wall St Terminal Regrade Park Virginia St Pier 70 Battery St Boren-Pike-Pine Park 4th Ave McGraw Stewart St Bell St Square 3rd Ave Olive Way Western Ave Pier 69 Blanchard St Boylston Ave 2nd Ave Summit Ave Lenora St Convention Center 1st Ave Pier 67 Alaskan Way Citywide Concierge Steinbrueck Westlake Center Park Park Bell Harbor International PIKE PLACE Pine St Conference Center Pike St Minor Ave Freeway Park Pier 66/Bell St. Boren Ave MARKET Union St Cruise Terminal Terry Ave Pier 62 & 63 University St 9th Ave N 8th Ave Seattle Aquarium Seneca St 7th Ave Pier 59 6th Ave SpringLIBRARY St W E Waterfront Park Post Alley 5th Ave 4th Ave Pier 57 Cherry St Elliott Bay James St Pier 56 Madison St S Pier 55 Pier 54 Marion St Alder St Columbia St Pier 52 Jefferson St Terrace City Hall Yesler Way WA State Pioneer Park Ferries Square Park Kobe S Washington St 2nd Ave S 3 Terrace Occidental rd (re-opens 2007) Park Square Ave S S Main St Pier 48 S Jackson St PIONEER Hing Hay Park SQUARE King St. -

Issue No. 3 (Fall)

THREE Ampersand PEOPLE & PLACE PUBLISHED BY FORTERRA DO NOT GO WHERE THE PATH MAY LEAD... BREAKING PAGE 1 TRAIL FIVE PEOPLE AND PROJECTS TO SUSTAIN OUR REGION IN THIS ISSUE A NOSE FOR CONSERVATION A trek to our state’s most northeastern corner with the humans and dogs of Conservation Canines. Florangela Davila is the editor of Ampersand. PAGE 7 KATRINA SPADE ON HUMAN COMPOSTING Designer Katrina Spade talks about human composting with Maureen O’Hagan, who has A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR written for The Seattle Times, The Washington Post and other publications. This third issue of Ampersand arrives after a sobering, PAGE 11 disquieting summer: the drought, fires, the deaths of three young firefighters, climate change and a New Yorker reminder that the great big earthquake HUNTING FOR “SUPER” WHEAT could arrive at any moment. All of these subjects give us pause and set Forterra running in the opposite Jacob Jones profiles one scientist’s response to direction: What gives us hope? climate change. Jones has written for the Pacific Northwest Inlander, Washington State Magazine Forterra publishes Ampersand so people will stay and various daily newspapers. invested in the future of this place. In this issue, we spotlight one of the Pacific Northwest's most defining PAGE 14 characteristics: our innovation. In the stories ahead, you’ll meet a handful of out-of-the-box thinkers and doers steeped in a desire to sustain this region. They’re working with dogs in some of our most BUILDING WITH CLT remote areas to help collect more information about Maria Dolan, a contributing writer for Seattle endangered species.