Arnold the Symphonist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

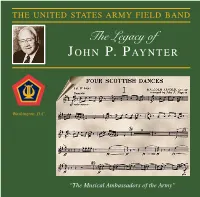

The Legacy of J O H N P

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND The Legacy of J OHN P. P AY N T E R Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” rom Boston to Bombay, Tokyo to Toronto, The United States Army Field Band has been thrilling audiences of all ages for more than half a century. As F the premier touring musical representative for the United States Army, this internationally-acclaimed organization travels thousands of miles each year presenting a variety of music to enthusiastic audiences throughout the nation and abroad. Through these concerts, the Field Band keeps the will of the American people behind the members of the armed forces and supports diplomatic efforts around the world. The Concert Band is the oldest and largest of the Field Band’s four performing components. This elite 65-member instrumental ensemble, founded in 1946, has per- formed in all 50 states and 25 foreign countries for audiences totaling more than 100 million. Tours have taken the band throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, South America, Europe, the Far East, and India. The group appears in a wide variety of settings, from world-famous concert halls, such as the Berlin Philharmonie and Carnegie Hall, to state fairgrounds and high school gymnasiums. The Concert Band regularly travels and performs with the Soldiers’ Chorus, together presenting a powerful and diverse program of marches, overtures, popular music, patriotic selections, and instrumental and vocal solos. The organization has also performed joint concerts with many of the nation’s leading orchestras, including the Boston Pops, Cincinnati Pops, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra. -

Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Concert Band

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-14-2016 Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Concert Band Jason M. Silveira Justin Cusick Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Concert Band; Silveira, Jason M.; and Cusick, Justin, "Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band" (2016). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1779. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1779 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Concert Band "Road Trip!" Jason M. Silveira, conductor Justin Cusick, graduate conductor Ford Hall Thursday, April 14th, 2016 8:15 pm Program New England Tritych (1957) William Schuman I. Be Glad Then, America (1910–1992) II. When Jesus Wept 17' III. Chester More Old Wine in New Bottles (1977) Gordon Jacob I. Down among the Dead Men (1895–1984) II. The Oak and the Ash 11' III. The Lincolnshire Poacher IV. Joan to the Maypole Justin Cusick, graduate conductor Intermission Four Cornish Dances (1966/1975) Malcolm Arnold I. Vivace arr. Thad Marciniak II. Andantino (1921–2006) III. Con moto e sempre senza parodia 10' IV. Allegro ma non troppo Homecoming (2008) Alex Shapiro (b. 1962) 7' The Klaxon (1929/1984) Henry Fillmore arr. Frederick Fennell (1881–1956) 3' Jason M. Silveira is assistant professor of music education at Ithaca College. He received his Bachelor of Music and Master of Music degrees in music education from Ithaca College, and his Ph. -

Cbarber Repertoire 2020.Pdf

Carolyn A. Barber University of Nebraska-Lincoln Conducting Repertoire, 2001-present UNL Wind Ensemble 2020 [April 28 concert cancelled due to COVID-19 precautions on campus] March 11, Kimball Recital Hall Joan Tower, Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman No. 1 (1987) Victoria Bond, The Indispensable Man (2010) *Nebraska premiere performance Felicia Sandler, Rosie the Riveter (2000) *Nebraska premiere performance Jonathan Newman, Symphony No. 1: My Hands Are a City (2009) 2019 December 11, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/4HBj7rIC6vk Gustav Holst, Suite in E-flat (1909) Percy Grainger, arr. Perna, Mock Morris (1910/2016) Joshua Cutting, doctoral associate conductor J.S. Bach, arr. N. Falcone, Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor (1712/1969) Gustav Holst, Bach’s Fugue à la Gigue (1707/1928) Rubén Gómez, doctoral associate conductor Percy Grainger, Colonial Song (1919/1997) Paul Hindemith, Symphony in B-flat (1951) October 2, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/RkzJB7msUuY Stephen Montague, Intrada 1631 (2003) Donald Grantham, Circa 1600 (2018) Kathryn Salfelder, Crossing Parallels (2011) Bob Margolis, Terpsichore (1981) Roberto Sierra, arr. Scatterday, Tumbao from Sinfonia No. 3 (2005/2009) *Nebraska premiere performance [Spring semester sabbatical – Newell Scholar at Georgia College] 2018 December 5, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/OwTWlg7jmiI Larry Tuttle, Across the Divide (2018) Carter Pann, The Three Embraces (2013) Cindy McTee, California Counterpoint: The Twittering Machine (1993) Carter Pann, My Brother’s Brain: A Symphony for Winds (2011) Carter Pann, Floyd’s Fantastic Five-Alarm Foxy Frolic (2009) October 3, Kimball Recital Hall Bernard Rogers, Three Japanese Dances: Dance with Pennons (1933/1956) Jennifer Jolley, The Eyes of the World Are Upon You (2017) *Nebraska premiere performance Frank Ticheli, Amazing Grace (1994) Rubén Gómez, doctoral associate conductor David Maslanka, Symphony No. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

Symphonic Band

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 10-18-1992 Symphonic Band Stephen K. Steele Conductor Illinois State University Daniel J. Farris Conductor Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Steele, Stephen K. Conductor and Farris, Daniel J. Conductor, "Symphonic Band" (1992). School of Music Programs. 901. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/901 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Music Department Illinois State University -, ·1 Symphonic Band I I I Stephen K. Steele & Daniel J. Farris, Conductors I Graduate Assistants I Jeffrey Allison John Eustace Amy Johnson I I Braden Auditorium I Sunday Afternoon October 18 I Twenty-Second program of the 1992-93 season. 3:00p.m. I 1 Program Eternal Father, Strong to Save (1975) Claude T. Smith Program Notes (1932-1988) Eternal Father, Strong to Save Claude T. Smith (1932-1988) was born in Missouri, educated in Kansas, and was active throughout the United States as an educator, a clinician, and a composer. Eternal Father, Strong to Save is based on the United States Navy Hymn. Written in ABA form, this exciting composition begins with a brilliant brass fanfare, Symphony No. 3 (1961) Vittorio Giannini followed by the horn stating the principle theme. -

Korngold, Alfred Newman, Philip Sainton, Adolph Deutsch, Hans J

570110-11bk Sea Hawk:570183bk Son of Kong 24/4/07 5:36 PM Page 24 John Morgan Widely regarded in film-music circles as a master colorist with a keen insight into orchestration and the power of music, Los Angeles-based composer John Morgan began his career working alongside such composers as Alex North and Fred Steiner before embarking on his own. Among other projects, he co-composed the richly dramatic score for the cult-documentary film Trinity and Beyond, described by one critic as “an atomic-age Fantasia, thanks to its spectacular nuclear explosions and powerhouse music.” In addition, Morgan has won acclaim for efforts to rescue, restore and re-record lost film scores from the past. Recently, Morgan composed the score for the acclaimed documentary, Cinerama Adventure. William Stromberg A native of Oceanside, California, who hails from a family of film-makers, William T. Stromberg balances his career as a composer of strikingly vivid film scores with that of a busy conductor in the original Marco Polo Classic Film Score Series. Besides conducting his own scores—including his music for the thriller Other Voices and the documentary Trinity and Beyond—Stromberg serves as a conductor for other film composers. He is especially noted for his passion in reconstructing and conducting film scores from Hollywood’s Golden Age, including several works recorded for RCA with the Brandenburg Philharmonic. For Marco Polo, he has conducted albums of music devoted to Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Alfred Newman, Philip Sainton, Adolph Deutsch, Hans J. Salter, Victor Young, Franz Waxman, Bernard Hermann and Malcolm Arnold. -

Old American Dances

ROBERT RUSSELL BENNETT Old American Dances ROYAL NORTHERN COLLEGE CLARK RUNDELL OF MUSIC WIND OrcHESTRA MARK HERON Robert Russell Bennett, 1941 Courtesy of George Ferencz Robert Russell Bennett (1894 – 1981) Suite of Old American Dances (1949)* 16:42 1 1 Cake Walk. Allegretto in two 3:44 2 2 Schottische. Moderato (in two or fast four) 2:30 3 3 Western One-Step. Allegro ma non troppo 3:08 4 4 Wallflower Waltz. Tempo di ‘Missouri Waltz’ (in three) 3:39 5 5 Rag. Gaily, in easy two 3:30 Down to the Sea in Ships (1968 – 69)† 14:02 from the NBC TV Film Project 20 6 I The Way of the Ship. Andante ‘Am Meer’ by Schubert – Intense (Moderato) – Vivo – ‘Blow the Man Down’ 3:30 7 II Mists and Mystery. Slow barcarolle 2:39 8 III Songs in the Salty Air. Moderato, in two – ‘Reuben Ranzo’ – Più animato – Allegretto ‘Haul on the Bowline’ – Moderato con sentimento ‘Shenandoah’ – Vivo – ‘What Shall We Do with a Drunken Sailor?’ – Tempo ad libitum – Presto 2:39 9 IV Waltz of the Clipper Ships. Con grazia, in one – ‘Sally Brown’ 2:12 10 V Finale, Introducing the S.S. Eagle. Bright – Subito agitato 2:49 3 Four Preludes for Band (1974)* 11:17 11 I George. Vigoroso – Espressivo – Moderato espressivo ‘To you, George’ 2:28 12 II Vincent. Allegretto – Not loud – ‘To you, Vincent’ 2:47 13 III Cole. Moderato, thoughtfully – ‘To you, Cole’ 2:58 14 IV Jerome. Vivo alla tarantella – Poco meno (Con grazia) – ‘To you, Jerome’ – Vivo come prima – Andante – Vivo, furioso 2:54 Symphonic Songs for Band (1957)† 14:09 15 I Serenade. -

Download Program Notes

Hoe-Down, from Rodeo Aaron Copland classical-music lover asked to describe pastorale, a lyric joke … . There are never A what constitutes “the American sound” more than a very few people on the stage has some tough deciding to do. For two- at a time … one must be always conscious and-a-quarter centuries, American com- of the enormous land on which these peo- posers have been producing music that is ple live and of their proud loneliness. so distinctive in its character that it simply couldn’t come from anywhere else. Fuging The ballet was received with enthusiasm. tunes by William Billings and his colleagues In the Chicago Tribune, the much-feared in Colonial New England, antebellum bal- critic Claudia Cassidy wrote: “Rodeo is a lads by Stephen Foster, irresistible marches smash hit. What Miss de Mille has turned out by John Philip Sousa, fearless experiments in this brilliant skirmish with Americana is a by Charles Ives, boundary-breaking synthe- shining little masterpiece.” ses by George Gershwin and Leonard Bern- To capture the profoundly national spirit stein, rhythmically vibrant effusions by of the subject, Copland drew directly from William Bolcom and John Adams — they all the well of American folk song, which was play irreplaceable parts in what makes our an obsession of composers at the time. nation’s “classical” music unique. And yet, Folk tunes (or melodies that mimic them) boiling it down to just one composer, many appear in quite a few Copland scores, but music lovers would agree that the seminal in Rodeo they play a role almost constant- summation of “the American sound” may be ly, drawn largely from the collections Our found in the scores of Aaron Copland. -

08 September 2019

08 September 2019 12:01 AM Malcolm Arnold (1921-2006), John P.Paynter (arranger) Little Suite for Brass Band No.1, Op 80 Edmonton Wind Ensemble, Harry Pinchin (conductor) CACBC 12:09 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Premiere rapsodie arr. for clarinet and orchestra (orig. clarinet and piano) Kari Kriikku (clarinet), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jukka-Pekka Saraste (conductor) FIYLE 12:17 AM Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) 3 Motets: Ave Maria; Christus factus est; Locus iste Sokkelund Choir, Morten Schuldt-Jensen (conductor) DKDR 12:30 AM Fanny Mendelssohn (1805-1847) Sonata in C minor (1824) Sylviane Deferne (piano) CACBC 12:45 AM Alexander Borodin (1833-1887), Unknown (transcriber) Notturno (Andante) - from String Quartet No.2 in D Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Oliver Dohnanyi (conductor) SKSR 12:54 AM George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (orchestrator) Overture and prelude to act II of Acis and Galatea K. 566 Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Andrew Manze (conductor) NONRK 01:04 AM Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Sonata for viola da gamba & basso continuo in A minor Camerata Koln, Rainer Zipperling (viola da gamba), Ghislaine Wauters (viola da gamba), Sabine Bauer (harpsichord) DEWDR 01:14 AM Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) 4 Songs Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Paul Turner (piano) GBBBC 01:23 AM Renaat Veremans (1894-1969) Nacht en Morgendontwaken aan de Nete Flemish Radio Orchestra, Bjarte Engeset (conductor) BEVRT 01:34 AM Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) Violin Concerto in D, Op 35 James Ehnes (violin), Vancouver Symphony -

PROGRAM NOTES Overture to “The Hebrides” (“Fingal's Cave”)

PROGRAM NOTES Overture to “The Hebrides” (“Fingal’s Cave”), Op. 26 (1830) Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Arr. Diana Appler Our concert will open with the “The Hebrides Overture”. Also known as “Fingal's Cave”, this piece was composed by Felix Mendelssohn in 1830. It was inspired by Mendelssohn's visit to Fingal's Cave on the island of Staffa, located in the Hebrides archipelago off the west coast of Scotland. As was common in the Romantic era, this is not an overture in the sense that it precedes a play or opera; it is a concert overture, a stand-alone musical selection, and has now become part of standard orchestral repertoire. It does not tell a specific story and is not "about" anything; instead, the piece depicts a mood and "sets a scene", making it an early example of such musical tone poems. The overture consists of two primary themes; the opening notes of the overture state the theme Mendelssohn wrote while visiting the cave, and is played initially in the orchestral version by the violas, cellos, and bassoons. This lyrical theme, suggestive of the power and stunning beauty of the cave, is intended to develop feelings of loneliness and solitude. The second theme, meanwhile, depicts movement at sea and "rolling waves". The opening to the overture is unmistakable and immediately recognizable, and has been used in numerous popular settings. Some may also recognize portions of this piece used as the "chase music" in the radio serial Challenge of the Yukon, featuring Sergeant Preston of the Mounties and his brave sled dog, Yukon King.