High Modernism and the History of Automatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Thing Poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge »

« Reflecting the Other: The Thing Poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge » by Vanessa Jane Robinson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto © Copyright by Vanessa Jane Robinson 2012 « Reflecting the Other: The Thing Poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge » Vanessa Jane Robinson Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Across continents and independently of one another, Marianne Moore (1887-1972) and Francis Ponge (1899-1988) both made names for themselves in the twentieth century as poets who gave voice to things. Their entire oeuvres are dominated by poems that attempt to reconstruct an external thing (inanimate object, plant or animal being) through language, while emphasizing the necessary distance that exists between the writing self and the written other. Furthermore, their thing poetry establishes an “essential otherness” to the subject of representation that (ideally) rejects an objectification of that subject, thereby rendering the “thing” a subject-thing with its own being-for-itself. This dissertation argues that the thing poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge successfully challenged the hierarchy between subject and object in representation by bringing the poet’s self into a dialogue with the encountered thing. The relationship between the writing self and the written other is akin to what Maurice Merleau-Ponty refers to in Le visible et l’invisible when he describes the act of perceiving what is visible as necessitating one’s own visibility to another. The other becomes a mirror of oneself and vice versa, Merleau-Ponty explains, to the extent that together they compose a single image. -

Cat151 Working.Qxd

Catalogue 151 election from Ars Libri’s stock of rare books 2 L’ÂGE DU CINÉMA. Directeur: Adonis Kyrou. Rédacteur en chef: Robert Benayoun. No. 4-5, août-novembre 1951. Numéro spé cial [Cinéma surréaliste]. 63, (1)pp. Prof. illus. Oblong sm. 4to. Dec. wraps. Acetate cover. One of 50 hors commerce copies, desig nated in pen with roman numerals, from the édition de luxe of 150 in all, containing, loosely inserted, an original lithograph by Wifredo Lam, signed in pen in the margin, and 5 original strips of film (“filmomanies symptomatiques”); the issue is signed in colored inks by all 17 contributors—including Toyen, Heisler, Man Ray, Péret, Breton, and others—on the first blank leaf. Opening with a classic Surrealist list of films to be seen and films to be shunned (“Voyez,” “Voyez pas”), the issue includes articles by Adonis Kyrou (on “L’âge d’or”), J.-B. Brunius, Toyen (“Confluence”), Péret (“L’escalier aux cent marches”; “La semaine dernière,” présenté par Jindrich Heisler), Gérard Legrand, Georges Goldfayn, Man Ray (“Cinémage”), André Breton (“Comme dans un bois”), “le Groupe Surréaliste Roumain,” Nora Mitrani, Jean Schuster, Jean Ferry, and others. Apart from cinema stills, the illustrations includes work by Adrien Dax, Heisler, Man Ray, Toyen, and Clovis Trouille. The cover of the issue, printed on silver foil stock, is an arresting image from Heisler’s recent film, based on Jarry, “Le surmâle.” Covers a little rubbed. Paris, 1951. 3 (ARP) Hugnet, Georges. La sphère de sable. Illustrations de Jean Arp. (Collection “Pour Mes Amis.” II.) 23, (5)pp. 35 illustrations and ornaments by Arp (2 full-page), integrated with the text. -

Bibliographie Fonds Ponge

Bibliothèque Denis Diderot Centre de documentation recherche Mas des Vergers (sans date), photographie anonyme. (Coll. A. Ponge) A partir du moment où l’on considère les mots (et les expressions verbales) comme une matière, il est très agréable de s’en occuper. Tout autant qu’il peut l’être pour un peintre de s’occuper des matières et des formes » (29 janvier 1954). Francis Ponge, Pratiques d’écriture ou l’inachèvement perpétuel. P., Hermann, 1984. Catalogue réalisé par Nadine Pontal responsable du fonds Francis Ponge au Centre de documentation recherche, Isabelle Brun responsable du catalogage à la bibliothèque de l’ENS et Caroline Yermia responsable des collections de revues à la bibliothèque de l’ENS, avec l’appui de Jean Marie Gleize, professeur émérite de l’ENS de Lyon et de Benoît Auclerc, Maître de conférences à l’Université Lyon3. Nous remercions l’ensemble des équipes de la bibliothèque ainsi qu’Antonello Marvulli et Vincent Brault du service Ens-médias pour leur participation à l’illustration et à la mise en forme de ce travail. Cette bibliographie est le reflet de l’état actuel des collections qui sont régulièrement enrichies par de nouvelles acquisitions et de nouveaux dons. Bibliographie | Bibliographie réalisée dans le cadre de l’exposition Ponge en regards organisée par la Bibliothèque de l’ENS de Lyon dans le hall de la bibliothèque Denis Diderot, du 15 mars au 4 mai 2012. L’exposition accompagne le colloque Politiques de Ponge des 15 et 16 mars 2012, organisé par le groupe Marge de l’Université Lyon 3 sous la direction de Jean- Marie Gleize, Benoît Auclerc et Bénédicte Gorrillot. -

French and Francophone Studies 1

French and Francophone Studies 1 www.brown.edu/academics/french-studies/undergraduate/honors- French and Francophone program/). Concentration Requirements Studies A minimum of ten courses is required for the concentration in French and Francophone Studies. Concentrators must observe the following guidelines when planning their concentration. It is recommended that Chair course choices for each semester be discussed with the department’s Virginia A. Krause concentration advisor. The Department of French and Francophone Studies at Brown promotes At least four 1000-level courses offered in the Department of 4 an intensive engagement with the language, literature, and cultural and French and Francophone Studies critical traditions of the French-speaking world. The Department offers At least one course covering a pre-Revolutionary period 1 both the B.A. and the PhD in French and Francophone Studies. Courses (i.e., medieval, Renaissance, 17th or 18th century France) cover a wide diversity of topics, while placing a shared emphasis on such as: 1 language-specific study, critical writing skills, and the vital place of FREN 1000A Littérature et intertextualité: du Moyen-Age literature and art for intellectual inquiry. Undergraduate course offerings jusqu'à la fin du XVIIème s are designed for students at all levels: those beginning French at Brown, FREN 1000B Littérature et culture: Chevaliers, those continuing their study of language and those undertaking advanced sorcières, philosophes, et poètes research in French and Francophone literature, culture and thought. Undergraduate concentrators and non-concentrators alike are encouraged FREN 1030A L'univers de la Renaissance: XVe et XVIe to avail of study abroad opportunities in their junior year, through Brown- siècles sponsored and Brown-approved programs in France or in another FREN 1030B The French Renaissance: The Birth of Francophone country. -

Artbook & Distributed Art Publishers Artbook D.A.P

artbook & distributed art publishers distributed artbook D.A.P. SPRING 2017 CATALOG Matthew Ronay, “Building Excreting Purple Cleft Ovoids” (2014). FromMatthew Ronay, published by Gregory R. Miller & Co. See page 108. FEATURED RELEASES 2 Journals 77 CATALOG EDITOR SPRING HIGHLIGHTS 84 Thomas Evans Art 86 ART DIRECTOR Writings & Group Exhibitions 117 Stacy lakefield Photography 122 IMAGE PRODUCTION Maddie Gilmore Architecture & Design 140 COPY lRITING Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Annabelle Maroney, Kyra Sutton SPECIALTY BOOKS 150 PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Art 152 Group Exhibitions 169 FRONT COVER IMAGE Photography 172 Kazimir Malevich, “Red House” (detail), 1932. From Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932, published by Royal Academy of Arts. See page 5. Backlist Highlights 178 BACK COVER IMAGE Dorothy Iannone, pages from A CookBook (1969). Index 183 From Dorothy Iannone: A CookBook, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 51. CONTRIBUTORS INCLUDE ■ BARRY BERGDOLL Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art and Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology, Department of Art History, Columbia University ■ JOHN MICHAEL DESMOND Professor, College of Art & Design, Louisiana State University ■ CAROLE ANN FABIAN Director, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University ■ JENNIFER GRAY Project Research Assistant, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art ■ ELIZABETH S. HAWLEY PhD Candidate, The Graduate Center, City University of New York ■ JULIET KINCHIN Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art ■ NEIL LEVINE Emmet Blakeney Gleason Research Professor of History of Art and Architecture, Modern Architecture, Harvard University ■ ELLEN MOODY Assistant Projects Conservator, The Museum of Modern Art ■ KEN TADASHI OSHIMA Professor, Department of Architecture, University of Washington Frank Lloyd Wright: Unpacking the Archive ■ MICHAEL OSMAN Edited by Barry Bergdoll, Jennifer Gray. -

POÉSIE ET POLITIQUE AU Xxe SIÈCLE

DU LUNDI 12 JUILLET (19 H) AU LUNDI 19 JUILLET (14 H) 2010 POÉSIE ET POLITIQUE AU XXe SIÈCLE DIRECTION : Henri BÉHAR, Pierre TAMINIAUX ARGUMENT : Ce colloque repose sur le désir d’éclairer d’un jour nouveau les rapports de la poésie de langue française du XXe siècle aux grands événements historiques et politiques qui ont traversé et à bien des égards défini ce siècle souvent tragique et tourmenté, du communisme au fascisme en passant par le colonialisme. Il tentera en particulier d’offrir des perspectives plus actuelles et détachées des simples circonstances de l’époque sur ces rapports afin de mieux cerner le caractère éternel et universel des questions éthiques et philosophiques qu’ils suscitent. Il s’agira de mettre en question une conception traditionnelle et trop commune de la poésie comme simple expression esthétique et formelle de l’homme et de son langage. À travers l’étude de mouvements modernistes essentiels, de dada au surréalisme en passant par le lettrisme, il importera ainsi de souligner l’importance déterminante de l’engagement du poète dans la communauté, et non de la poésie. Celle-ci s’y est-elle compromise à jamais? Les rapports étroits et complexes de personnalités telles que Tristan Tzara, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, Robert Desnos, Louis Aragon pour le dadaïsme et le surréalisme, ou de Christian Dotremont, pour Cobra, à l’idée de révolution envisagée dans sa détermination poétique seront considérés comme des exemples fondamentaux permettant de nourrir et de développer notre problématique. Ne seront pas oubliés non plus le parcours original de figures singulières, de René Char à Francis Ponge en passant par Aimé Césaire, qui ont accompagné de manière radicale et existentielle les actions de la résistance à l’occupation nazie ou la lutte des peuples du tiers-monde pour leur indépendance ni l’utilisation politique de la poésie moderne par le mouvement de mai 68, ni les possibilités d’expression subversive offertes par l’avant-garde de l’Internationale lettriste. -

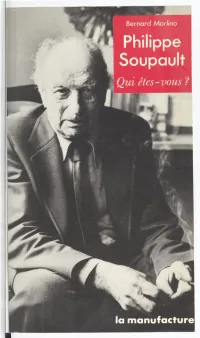

PHILIPPE SOUPAULT Qui Êtes-Vous ?

Dans la même collection : FREDERIC DARD par Louis Bourgeois JEAN GIONO par Jean Carrière MARGUERITE YOURCENAR par Georges Jacquemin ALAIN ROBBE-GRILLET par Jean-Jacques Brochier VLADIMIR JANKELEVITCH par Guy Suarès LE CORBUSIER par Gérard Monnier FRANCIS PONGE par Guy Lavorel JEAN PAULHAN par André Dhôtel MICHEL FOUCAULT par Jean-Marie Auzias HENRY MILLER par Frédéric-Jacques Temple RAYMOND ARON par Nicolas Baverez GUSTAVE ROUD par Gilbert Salem JULIEN GRACQ par Jean Carrière CARSON McCULLERS par Jacques Tournier SAINT-JOHN PERSE par Guy Féquant ALAIN RESNAIS par Jean-Daniel Roob ANTONIN ARTAUD par Alain et Odette Virmaux (accompagné d'une cassette de l'enregistrement de Pour en finir avec le jugement de dieu d'A. Artaud) NATHALIE SARRAUTE par Simone Benmussa PAUL-JEAN TOULET par Pierre-Olivier Walzer EMMANUEL LEVINAS par François Poirié ELIE WIESEL par Brigitte-Fanny Cohen ANDRE MALRAUX par Jeanine Mossuz-Lavau COLETTE par Jeannie Malige PIER PAOLO PASOLINI par Alain-Michel Boyer JEAN VILAR par Alfred Simon (accompagné d'une cassette de l'enregistrement des grands rôles de Jean Vilar au théâtre) JEAN DASTÉ par Jean Dasté ANDRÉ BRETON par Alain et Odette Virmaux VIRGINIA WOOLF par Phillys Rose RENÉ CHAR par Serge Velay A paraître HENRI MATISSE par Marcellin Pleynet MAURICE RAVEL par Marcel Marnat (accompagné d'une cassette des enregistrements de Maurice Ravel réalisés par lui-même ou sous sa direction) CLAUDE LÉVI-STRAUSS par Jean-Marie Benoist RAYMOND QUENEAU par Jacques Jouet KATHERINE MANSFIELD par Michel Dupuis Les ouvrages marqués d'un astérisque comportent des entretiens issus des archives de l'Institut national de l'audiovisuel. -

C a P I L a N O UNIVERSITY COURSE OUTLINES TERM: FALL 2016 COURSE NO: English 326 INSTRUCTOR: COURSE NAME: Traditions in Poetry

C A P I L A N O UNIVERSITY COURSE OUTLINES TERM: FALL 2016 COURSE NO: English 326 INSTRUCTOR: COURSE NAME: Traditions in Poetry OFFICE: LOCAL: SECTION NO(S): CREDITS: 3 E-MAIL: OFFICE HOURS: COURSE FORMAT Three hours of class time, plus an additional hour delivered through on-line or other activities for a 15 week semester, which includes two weeks for final exams. COURSE PREREQUISITES 45 credits of 100 level or higher coursework, including 6 credits of 100- or 200-level ENGL COURSE DESCRIPTION A survey of poetry traditions and practices across different times and cultures with particular attention to the emergence of new forms and theories of poetry. A specific section of the course may select a particular time period and place, e.g. medieval poetry in England, France, and Japan. The course will examine a selection of works critically and from several theoretical perspectives. This section of English 326 examines twentieth century modernist poetry. COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to: Read a variety of poems and essays critically and thoughtfully Develop various critical approaches to the works Conduct research and write critically searching essays Write a research essay which includes secondary sources documented in MLA style Present ideas orally both alone and as part of a group COURSE WEBSITE Students will be expected to consult the course Moodle page on a regular basis. Many of the required texts will be offered online. REQUIRED TEXTS Access Coursepack. Perloff, Marjorie. The Futurist Moment. (on reserve in the Library) Perloff, Marjorie. -

Francis Ponge Unfinished Ode To

also by Beverley Bie Brahic POETRY Against Gravity Francis Ponge TRANSLATIONS Hélène Cixous, Hyperdream Hélène Cixous, Manhattan Unfinished Ode Hélène Cixous, Dream I Tell You Hélène Cixous and Roni Horn, Agua Viva (Rings of Lispector) Hélène Cixous, The Day I Wasn’t There to Mud Hélène Cixous, Reveries of the Wild Woman Hélène Cixous, Portrait of Jacques Derrida as a Young Jewish Saint Jacques Derrida, Geneses, Genealogies, Genres and Genius poems translated by OTHER Beverley Bie Brahic the eye goes after (digital images by Susan Cantrick accompanying poems by Beverley Bie Brahic) b editions C Contents Biographical Note vii from Le Parti pris des choses / The Defence of Things Pluie / Rain 2 La Fin de l’automne / The End of Autumn 4 Les Mûres / The Blackberries 6 Le Cageot / The Crate 8 La Bougie / The Candle 10 L’Orange / The Orange 12 L’Huître / The Oyster 14 Les Plaisirs de la porte / The Delights of the Door 16 Le Mollusque / The Mollusc 18 First published in 2008 Le Papillon / The Butterfly 20 by CB editions La Mousse / Moss 22 146 Percy Road London W12 9QL Le Morceau de viande / The Piece of Meat 24 www.cbeditions.com Le Restaurant Lemeunier / Lemeunier Restaurant 26 Reprinted 2009 Notes pour un coquillage / Notes towards a Shell 32 All rights reserved Le Galet / The Pebble 38 Poems © Gallimard 1942 (Le Parti pris des choses), 1971 (Pièces) Translations © Beverley Bie Brahic 2008 from Pièces / Pieces The right of Beverley Bie Brahic to be identified La Barque / The Boat 56 as translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Fabri, ou le jeune ouvrier / Fabri, or The Young Worker 58 Éclaircie en hiver / Winter Clearing 60 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Maisonneuve Magazine (Montreal) and to A Public Space (New York) Le Paysage / The Landscape 62 in which some of these translations were originally published. -

Ars Libri Ltd Modernart

MODERNART ARS LIBRI LT D 149 C ATALOGUE 159 MODERN ART ars libri ltd ARS LIBRI LTD 500 Harrison Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02118 U.S.A. tel: 617.357.5212 fax: 617.338.5763 email: [email protected] http://www.arslibri.com All items are in good antiquarian condition, unless otherwise described. All prices are net. Massachusetts residents should add 6.25% sales tax. Reserved items will be held for two weeks pending receipt of payment or formal orders. Orders from individuals unknown to us must be accompanied by pay- ment or by satisfactory references. All items may be returned, if returned within two weeks in the same con- dition as sent, and if packed, shipped and insured as received. When ordering from this catalogue please refer to Catalogue Number One Hundred and Fifty-Nine and indicate the item number(s). Overseas clients must remit in U.S. dollar funds, payable on a U.S. bank, or transfer the amount due directly to the account of Ars Libri Ltd., Cambridge Trust Company, 1336 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02238, Account No. 39-665-6-01. Mastercard, Visa and American Express accepted. June 2011 avant-garde 5 1 AL PUBLICO DE LA AMERICA LATINA, y del mondo entero, principalmente a los escritores, artistas y hombres de ciencia, hacemos la siguiente declaración.... Broadside poster, printed in black on lightweight pale peach-pink translucent stock (verso blank). 447 x 322 mm. (17 5/8 x 12 3/4 inches). Manifesto, dated México, sábado 18 de junio de 1938, subscribed by 36 signers, including Manuel Alvárez Bravo, Luis Barragán, Carlos Chávez, Anto- nio Hidalgo, Frieda [sic] Kahlo, Carlos Mérida, César Moro, Carlos Pellicer, Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, Frances Toor, and Javier Villarrutia. -

AVANT-GARDE MODERN AVANT-GARDE Catalogue 151 a Selection from Ars Libri’S Stock of Rare Books

ARS LIBRI Catalogue 151 MODERN AVANT-GARDE MODERN AVANT-GARDE Catalogue 151 A selection from Ars Libri’s stock of rare books 2 L’ÂGE DU CINÉMA. Directeur: Adonis Kyrou. Rédacteur en chef: Robert Benayoun. No. 4-5, août-novembre 1951. Numéro spé- cial [Cinéma surréaliste]. 63, (1)pp. Prof. illus. Oblong sm. 4to. Dec. wraps. Acetate cover. One of 50 hors commerce copies, desig- nated in pen with roman numerals, from the édition de luxe of 150 in all, containing, loosely inserted, an original lithograph by Wifredo Lam, signed in pen in the margin, and 5 original strips of film (“filmomanies symptomatiques”); the issue is signed in colored inks by all 17 contributors—including Toyen, Heisler, Man Ray, Péret, Breton, and others—on the first blank leaf. Opening with a classic Surrealist list of films to be seen and films to be shunned (“Voyez,” “Voyez pas”), the issue includes articles by Adonis Kyrou (on “L’âge d’or”), J.-B. Brunius, Toyen (“Confluence”), Péret (“L’escalier aux cent marches”; “La semaine dernière,” présenté par Jindrich Heisler), Gérard Legrand, Georges Goldfayn, Man Ray (“Cinémage”), André Breton (“Comme dans un bois”), “le Groupe Surréaliste Roumain,” Nora Mitrani, Jean Schuster, Jean Ferry, and others. Apart from cinema stills, the illustrations includes work by Adrien Dax, Heisler, Man Ray, Toyen, and Clovis Trouille. The cover of the issue, printed on silver foil stock, is an arresting image from Heisler’s recent film, based on Jarry, “Le surmâle.” Covers a little rubbed. Paris, 1951. $2,750.00 3 (ARP) Hugnet, Georges. La sphère de sable. -

Librairie Faustroll

LIBRAIRIE FAUSTROLL The 58th Annual New York International Antiquarian Book Fair Park Avenue Armory Booth D26 March 8-11, 2018 LIBRAIRIE FAUSTROLL First editions - Illustrated books Manuscripts - Etchings - Photographs Christophe Champion 22, rue du Delta 75009 Paris France Tel : +33 (0)6 67 17 08 42 e-mail : [email protected] By appointment Please visit our website at: http://www.librairie-faustroll.com LCL 31 bis rue Vivienne, 75002 Paris Account: 402 375428J IBAN: FR96 3000 2004 0200 0037 5428 J43 R.C.S. Paris 512 913 765 VAT: FR43 512 913 765 presentation copies of FIVE BECKETT’s first editions 1. BECKETT (Samuel). Comment c’est. Paris, Editions de Minuit, 1961. 18,7 x 12 cm, in printed wrappers as issued, 177 pp.. First edition. One of 87 numbered copies printed on alfa mousse (110 copies were printed on the same paper for "Le Club de l’Édition Originale"), our copy being one of 7 "not for sale" copies. Inscribed and signed by Samuel Beckett on the title page : « Pour Claude de Capdenac / bien amica- lement / Sam. Beckett / paris janvier 1961 ». Claude de Capdenac has spent his whole career working for Éditions de Minuit from the mid 50s. He was in charge of production. $1,500. 2. BECKETT (Samuel). Immobile. Paris, Editions de Minuit, 1976. 19,1 x 14,2 cm, in printed wrappers as issued, 14 pp.. First edition. One of 125 numbered copies printed on vélin d’Arches (our copy being one of 25 "not for sale" copies), sole large paper edition. Inscribed and signed by Samuel Beckett on the title page : « Pour / Sylvie Peltier / bien amicalement / Sam.