Colin M. Hamilton Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad Radio 106,2

#WhoWeAre To become the largest Music Media and Services organization in the countries we operate, providing services and products which cover all communication & media platforms, satisfying directly and efficiently both our client’s and our audience’s needs, maintaining at the same time our brand's creative and subversive character. #MISSION #STRUCTURE NEW MEDIA TV EVENTS RADIO WEB INTERNATIONAL & SERVICES MAD 106,2 Mad TV www.mad.gr DIGITAL VIDEO MUSIC MadRADIO Mad TV CYPRUS GREECE MARKETING AWARDS Mad HITS/ CONTENT Mad TV MADWALK 104FM SOCIAL MEDIA OTE Conn-x SERVICES ALBANIA Mad GREEKζ/ MAD MUSIC ANTENNA EUROSONG NOVA @NOVA SATELLITE MAD PRODUCTION NORTH STAGE Dpt FESTIVAL YouTube #TV #MAD TV GREECE • Hit the airwaves on June 6th, 1996 • One of the most popular music brands in Greece*(Focus & Hellaspress) • Mad TV has the biggest digital database of music content in Greece: –More than 20.000 video clips –250.000 songs –More than 1.300 hours of concerts and music documentaries –Music content database with tens of thousands music news, biographical information –and photographic material of artists, wallpapers, ring tones etc. • Mad TV has deployed one of the most advanced technical infrastructures and specialized IT/Technical/ Production teams in Greece. • Mad TV Greece is available on free digital terrestrial, cable, IPTV, satellite and YouTube all over Greece. #PROGRAM • 24/7 youth program • 50% International + 50% Greek Music • All of the latest releases from a wide range of music genres • 30 different shows/ week (21 hours of live -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

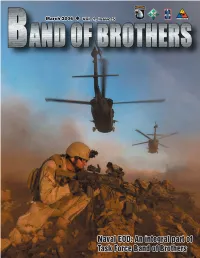

An Integral Part of Task Force Band of Brothers

March 2006 Vol. 1, Issue 5 Naval EOD: An integral part of Task Force Band of Brothers Two Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division sit on stage for a comedy skit with actress Karri Turner, most known for her role on the television series JAG, and comedians Kathy Griffin, star of reality show My Life on the D List and Michael McDonald, star of MAD TV. The three celebrities performed a number of improv skits for Soldiers and Airmen of Task Force Band of Brothers at Contingency Operating Base Speicher in Tikrit, Iraq, Mar. 17, as part of the Armed Forces Entertainment tour, “Firing at Will.” photo by Staff Sgt. Russell Lee Klika Inside... In every issue... Hope in the midst of disaster Page 5 Health and Fitness: Page 9 40 Ways to Eat Better Bastogne Soldiers cache in their tips Page 6-7 BOB on the FOB Page 20 Combat support hospital saves lives Page 8 Your new favorite cartoon! Aviation Soldiers keep perimeter safe Page 10 Hutch’s Top 10 Page 21 Fire Away! Page 11 On the cover... Detention facility goes above and beyond Page 12 Soldier writes about women’s history Page 13 U.S. Navy Explosive Or- Project Recreation: State adopts unit Page 16-17 dinance Disposal tech- nician Petty Officer 2nd Albanian Army units work with Page 18-19 Class Scott Harstead and Soldiers from the Coalition Forces in war on terrorism 1st Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Di- FARP guys keep helicopters in fight Page 22 vision dismount a UH- 60 Blackhawk from the Mechanics make patrols a success Page 23 101st Airborne Division during an Air Assault in the Ninevah Province, Soldier’s best friend Page 24 Iraq, Mar. -

The Thing Poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge »

« Reflecting the Other: The Thing Poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge » by Vanessa Jane Robinson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto © Copyright by Vanessa Jane Robinson 2012 « Reflecting the Other: The Thing Poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge » Vanessa Jane Robinson Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Across continents and independently of one another, Marianne Moore (1887-1972) and Francis Ponge (1899-1988) both made names for themselves in the twentieth century as poets who gave voice to things. Their entire oeuvres are dominated by poems that attempt to reconstruct an external thing (inanimate object, plant or animal being) through language, while emphasizing the necessary distance that exists between the writing self and the written other. Furthermore, their thing poetry establishes an “essential otherness” to the subject of representation that (ideally) rejects an objectification of that subject, thereby rendering the “thing” a subject-thing with its own being-for-itself. This dissertation argues that the thing poetry of Marianne Moore and Francis Ponge successfully challenged the hierarchy between subject and object in representation by bringing the poet’s self into a dialogue with the encountered thing. The relationship between the writing self and the written other is akin to what Maurice Merleau-Ponty refers to in Le visible et l’invisible when he describes the act of perceiving what is visible as necessitating one’s own visibility to another. The other becomes a mirror of oneself and vice versa, Merleau-Ponty explains, to the extent that together they compose a single image. -

Local Public Health Office to Close

SERVING EASTERN SHASTA, NORTHERN LASSEN, WESTERN MODOC & EASTERN SISKIYOU COUNTIES 70 Cents Per Copy Vol. 45 No. 43 Burney, California Telephone (530) 335-4533 FAX (530) 335-5335 Internet: im-news.com E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 7, 2004 Local public health offi ce to close BY MEG FOX the state’s Vehicle License Fee who have been notifi ed about their “Our staff traveled to nine com- programs and services. Six public health employees will (VLF). But the money to make up jobs are Community Health Advo- munities to do the fl u clinics,” said The Burney regional offi ce par- be laid off and access to numerous the state’s $10.5 billion defi cit had to cate Claudia Woods, Community Moore, adding that she doesn’t ticipated on the Intermountain Injury local services will end when Shasta come from somewhere and public Organizer Laura Thompson, Com- know how many, if any, fl u clinics Prevention Coalition, the Physical County Public Health closes the health is one of several targets. munity Health Advocates Manuel the county will be able to provide Activity and Nutrition team (PANT), doors of the Burney Regional offi ce “Shasta County Public Health is Meza and Kenia Howard, and Medi- locally. Intermountain Breastfeeding Coali- on Feb. 20. losing about a third of its funding cal Services Clerk Jennifer Cearley. “It’s not looking good,” she said. tion, Intermountain Area Domestic “We fi nally got more services up until the state fi nds another way to The department plans to retain The Burney staff worked with the Violence Coordinating Council, here and now they’re going away,” pay for local public health,” Moore Public Health Nurse David Moe- schools to improve physical activ- and Intermountain Hispanic/Latino said Community Development said. -

Spring 2007 Newsletter

Dance Studio Art Create/Explore/InNovate DramaUCIArts Quarterly Spring 2007 Music The Art of Sound Design in UCI Drama he Drama Department’s new Drama Chair Robert Cohen empa- a professor at the beginning of the year, graduate program in sound sized the need for sound design initia- brings a bounty of experience with him. design is a major step in the tive in 2005 as a way to fill a gap in “Sound design is the art of provid- † The sound design program Tdepartment’s continuing evolution as the department’s curriculum. “Sound ing an aural narrative, soundscape, contributed to the success of Sunday in The Park With George. a premier institution for stagecraft. design—which refers to all audio reinforcement or musical score for generation, resonation, the performing arts—namely, but not performance and enhance- limited to, theater,” Hooker explains. ment during theatrical or “Unlike the recording engineer or film film production—has now sound editor, we create and control become an absolutely the audio from initial concept right vital component” of any down to the system it is heard on.” quality production. He spent seven years with Walt “Creating a sound Disney Imagineering, where he designed design program,” he con- sound projects for nine of its 11 theme tinued, “would propel UCI’s parks. His projects included Cinemagique, Drama program—and the an interactive film show starring actor collaborative activities of Martin Short at Walt Disney Studios its faculty—to the high- Paris; the Mermaid Lagoon, an area fea- est national distinction.” turing several water-themed attractions With the addition of at Tokyo Disney Sea; and holiday overlays Michael Hooker to the fac- for the Haunted Mansion and It’s a Small ulty, the department is well World attractions at Tokyo Disneyland. -

Weekend Movie Schedule Photo Can Be Fixed

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 12, 2006 5 MONDAY EVENING MAY 15, 2006 brassiere). However, speaking as a 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 fellow sugar addict, my advice is to E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Photo can be fixed start cutting back on the sugar, be- The First 48: Twisted Tattoo Fixation Influences; Inked Inked Crossing Jordan (TV14) The First 48: Twisted 36 47 A&E DEAR ABBY: My husband, cause not only is it addictive, it also Honor; Vultures designs. (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (HD) Honor; Vultures abigail Oprah Winfrey’s Legends Grey’s Anatomy: Deterioration of the Fight or Flight KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live “Keith,” and I are eagerly awaiting makes you crave more and more. And 4 6 ABC an hour after you’ve consumed it, Ball (N) Response/Losing My Religion (N) (HD) at 10 (N) (TV14) the birth of our first child. Sadly, van buren Animal Precinct: New Be- Miami Animal Police: Miami Animal Police: Animal Precinct: New Be- Miami Animal Police: Keith’s mother is in very poor health. you’ll feel as fatigued as you felt “en- 26 54 ANPL ginnings (TV G) Gators Galore (TVPG) Gator Love Bite ginnings (TV G) Gators Galore (TVPG) ergized” immediately afterward. The West Wing: Tomor- “A Bronx Tale” (‘93, Drama) Robert De Niro. A ‘60s bus driver “A Bronx Tale” (‘93, Drama) A man She’s not expected to live more than 63 67 BRAVO a few months after the birth of her dear abby DEAR ABBY: I was adopted by a row (TVPG) (HD) struggles to bring up his son right amid temptations. -

Download This PDF File

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2020 2020, Vol. 7, No. 3, 142-162 ISSN: 2149-1291 http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/392 Racism’s Back Door: A Mixed-Methods Content Analysis of Transformative Sketch Comedy in the US from 1960-2000 Jennifer Kim1 Independent Scholar, USA Abstract: Comedy that challenges race ideology is transformative, widely available, and has the potential to affect processes of identity formation and weaken hegemonic continuity and dominance. Outside of the rules and constraints of serious discourse and cultural production, these comedic corrections thrive on discursive and semiotic ambiguity and temporality. Comedic corrections offer alternate interpretations overlooked or silenced by hegemonic structures and operating modes of cultural common sense. The view that their effects are ephemeral and insignificant is an incomplete and misguided evaluation. Since this paper adopts Hegel’s understanding of comedy as the spirit (Geist) made material, its very constitution, and thus its power, resides in exposing the internal thought processes often left unexamined, bringing them into the foreground, dissecting them, and exposing them for ridicule and transformation. In essence, the work of comedy is to consider all points of human processing and related structuration as fair game. The phenomenological nature of comedy calls for a micro-level examination. Select examples from The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1968), The Richard Pryor Show (1977), Saturday Night Live (1990), and Chappelle’s Show (2003) will demonstrate representative ways that comedy attacks and transforms racial hegemony. Keywords: comedy, cultural sociology, popular culture, race and racism, resistance. During periods of social unrest, what micro-level actions are available to the public? Or, how does a particular society respond to inequities that are widely shared and agreed upon as intolerable aspects of a society? One popular method to challenge a hegemonic structure, and to survive it, is comedy. -

The BG News April 2, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-2-1999 The BG News April 2, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 2, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6476. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6476 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. .The BG News mostly cloudy New program to assist disabled students Office of Disability Services offers computer program that writes what people say However, he said, "They work together," Cunningham transcripts of students' and ities, so they have an equal By IRENE SHARON (computer programs] are far less said. teachers' responses. This will chance of being successful. high: 69 SCOTT than perfect." Additionally, the Office of help deaf students to participate "We try to minimize the nega- The BG News Also, in the fall they will have Disability Services hopes to start in class actively, he said. tives and focus on similarities low: 50 The Office of Disability Ser- handbooks available for teachers an organization for disabled stu- Several disabled students rather than differences," he said. vices for Students is offering and faculty members, so they dents. expressed contentment over the When Petrisko, who has pro- additional services for the dis- can better accommodate dis- "We are willing to provide the services that the office of disabil- found to severe hearing loss, was abled community at the Univer- abled students. -

Saturday and Sunday Movies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 28, 2004 5 abigail your help, Abby — it’s been an aw- dinner in the bathroom with her. I behavior is inappropriate. Your parents remember leaving me home Co-worker ful burden. — OLD-FASHIONED find his behavior questionable and daughter is old enough to bathe with- alone at that age, but that was 24 van buren IN BOULDER have asked him repeatedly to allow out supervision and should do so. years ago. I feel things are too dan- DEAR OLD-FASHIONED: Talk her some privacy. Nonetheless, he You didn’t mention how physically gerous these days. creates more to the supervisor privately and tell continues to “assist her” in bathing developed she is, but she will soon Is there an age when I can leave •dear abby him or her what you have told me. by adding bath oil to the water, etc. be a young woman. Your husband’s them home alone and know that all work for others Say nothing to Ginger, because that’s Neither my husband nor my daugh- method of “lulling” her to sleep is is OK? — CAUTIOUS MOM IN DEAR ABBY: I work in a large, breaks, sometimes even paying her the supervisor’s job — and it will ter thinks anything is wrong with this also too stimulating for both of them. KANSAS open office with five other people. bills and answering personal corre- only cause resentment if you do. behavior — so what can I do? Discuss this with your daughter’s DEAR CAUTIOUS MOM: I’m We all collaborate on the same spondence on company time. -

Érika Pinto De Azevedo

ÉRIKA PINTO DE AZEVEDO UNE ÉTUDE ET UNE TRADUCTION DE L’HOMME AU COMPLET GRIS CLAIR , NOUVELLE DE MARCEL LECOMTE, ÉCRIVAIN SURRÉALISTE BELGE FRANCOPHONE PORTO ALEGRE ABRIL 2007 1 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS ÁREA DE ESTUDOS DE LITERATURA ÊNFASE: LEM - LITERATURAS FRANCESA E FRANCÓFONAS Linha de Pesquisa: Teorias Literárias e Interdisciplinaridade UNE ÉTUDE ET UNE TRADUCTION DE L’HOMME AU COMPLET GRIS CLAIR , NOUVELLE DE MARCEL LECOMTE, ÉCRIVAIN SURRÉALISTE BELGE FRANCOPHONE Érika Pinto de Azevedo Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da UFRGS como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Letras, área de Estudos de Literatura, ênfase de LEM - Literaturas Francesa e Francófonas Orientador: Prof. Dr. Robert Ponge Porto Alegre, UFRGS 2007 2 TABLE DES MATIÈRES INTRODUCTION CHAPITRE 1 NAISSANCE ET DÉVELOPPEMENT DU SURRÉALISME AUTOUR D’ANDRÉ BRETON JUSQU’EN 1931 ANDRÉ BRETON DE 1896 À 1913 10 LA « DÉCOUVERTE DE LA RÉSISTANCE ABSOLUE » (1913-1918) 11 DE LA FONDATION DE LITTÉRATURE AU LANCEMENT DU 13 SURRÉALISME (1919-1924) DU MANIFESTE (1924) AU SECOND MANIFESTE DU SURRÉALISME (1929- 21 1930) ET UN PEU APRÈS CHAPITRE 2 QUELQUES ÉLÉMENTS D’HISTOIRE DU DADAÏSME ET DU SURRÉALISME EN BELGIQUE JUSQU’EN 1931 CLÉMENT PANSAËRS ET LE DADAÏSME 28 QUELQUES REVUES NOVATRICES OU MODERNISTES 30 RENCONTRES INITIALES DES FUTURS SURRÉALISTES (1919-1924) 31 CORRESPONDANCE , ŒSOPHAGE ET MARIE (1924-1926) 32 FORMATION ET PREMIÈRES ACTIVITÉS DU GROUPE SURRÉALISTE -

Cat151 Working.Qxd

Catalogue 151 election from Ars Libri’s stock of rare books 2 L’ÂGE DU CINÉMA. Directeur: Adonis Kyrou. Rédacteur en chef: Robert Benayoun. No. 4-5, août-novembre 1951. Numéro spé cial [Cinéma surréaliste]. 63, (1)pp. Prof. illus. Oblong sm. 4to. Dec. wraps. Acetate cover. One of 50 hors commerce copies, desig nated in pen with roman numerals, from the édition de luxe of 150 in all, containing, loosely inserted, an original lithograph by Wifredo Lam, signed in pen in the margin, and 5 original strips of film (“filmomanies symptomatiques”); the issue is signed in colored inks by all 17 contributors—including Toyen, Heisler, Man Ray, Péret, Breton, and others—on the first blank leaf. Opening with a classic Surrealist list of films to be seen and films to be shunned (“Voyez,” “Voyez pas”), the issue includes articles by Adonis Kyrou (on “L’âge d’or”), J.-B. Brunius, Toyen (“Confluence”), Péret (“L’escalier aux cent marches”; “La semaine dernière,” présenté par Jindrich Heisler), Gérard Legrand, Georges Goldfayn, Man Ray (“Cinémage”), André Breton (“Comme dans un bois”), “le Groupe Surréaliste Roumain,” Nora Mitrani, Jean Schuster, Jean Ferry, and others. Apart from cinema stills, the illustrations includes work by Adrien Dax, Heisler, Man Ray, Toyen, and Clovis Trouille. The cover of the issue, printed on silver foil stock, is an arresting image from Heisler’s recent film, based on Jarry, “Le surmâle.” Covers a little rubbed. Paris, 1951. 3 (ARP) Hugnet, Georges. La sphère de sable. Illustrations de Jean Arp. (Collection “Pour Mes Amis.” II.) 23, (5)pp. 35 illustrations and ornaments by Arp (2 full-page), integrated with the text.