Historical Background of the Himalayan Frontier of India 1959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{Download PDF} the Formation of the Colonial State in India 1St Edition

THE FORMATION OF THE COLONIAL STATE IN INDIA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tony Cleaver | 9781134494293 | | | | | The Formation of the Colonial State in India 1st edition PDF Book Additionally, several Indian Princely States provided large donations to support the Allied campaign during the War. Under the charter, the Supreme Court, moreover, had the authority to exercise all types of jurisdiction in the region of Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha, with the only caveat that in situations where the disputed amount was in excess of Rs. During this age India's economy expanded, relative peace was maintained and arts were patronized. Routledge Handbook of Gender in South Asia. British Raj. Two four anna stamps issued in Description Contents Reviews Preview "Colonial and Postcolonial Geographies of India offers a good introduction to and basis for rethinking the ways in which academics theorize and teach the geographies of peoples, places, and regions. Circumscription theory Legal anthropology Left—right paradigm State formation Political economy in anthropology Network Analysis and Ethnographic Problems. With the constituting of the Ceded and Conquered Provinces in , the jurisdiction would extend as far west as Delhi. Contracts were awarded in to the East Indian Railway Company to construct a mile railway from Howrah -Calcutta to Raniganj ; to the Great Indian Peninsular Railway Company for a service from Bombay to Kalyan , thirty miles away; and to the Madras Railway Company for a line from Madras city to Arkonam , a distance of some thirty nine miles. The interdisciplinary work throws new light on pressing contemporary issues as well as on issues during the colonial period. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

Devaluating the Nandas -A Big Loss to the History of India

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 9, Ver. 8 (Sep. 2016) PP 17-20 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Devaluating The Nandas -A Big Loss To The History Of India SANJAY CHAUDHARI Department Of History,Culture And Archaeology, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Avadh University, Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract: Indian historians could be blamed for having hostile attitude towards the Nandas. Though Nandas established the first ever empire, covering almost area of present India, they were never recognized for the same. Almost Indian historians neglected their acheivements and have tried to reduce the span of their rule. The Nandas have been referred by distant people of ancient Iran and the classical writers of the Greece. Their strength has been narrated by the scholars who accompanied Alexander in India. Interesting to state that no evidences are available which could confirm the war, that took place between the last Nanda and Chandragupta. Even though the historians narrated the event stating it as a revolution by the people which ousted the last Nanda king. There are few Sanskrit chronicles which connected Chandragupta to Nanda King. These chronicles have stated that Chandragupta was the legitimate son of the last Nanda king. But Indian historians tried their best to present Buddhist evidences which state Chandragupta a resident of Pippalvana and related to Nandas any way. To devaluate the Nandas has created a big historical loss to our ancient history. The whole period from Indus valley civilization to the establishment of sixteen Mahajanapadas is still in the dark. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

The Gupta Empire: an Indian Golden Age the Gupta Empire, Which Ruled

The Gupta Empire: An Indian Golden Age The Gupta Empire, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 320 to 550 AD, ushered in a golden age of Indian civilization. It will forever be remembered as the period during which literature, science, and the arts flourished in India as never before. Beginnings of the Guptas Since the fall of the Mauryan Empire in the second century BC, India had remained divided. For 500 years, India was a patchwork of independent kingdoms. During the late third century, the powerful Gupta family gained control of the local kingship of Magadha (modern-day eastern India and Bengal). The Gupta Empire is generally held to have begun in 320 AD, when Chandragupta I (not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire), the third king of the dynasty, ascended the throne. He soon began conquering neighboring regions. His son, Samudragupta (often called Samudragupta the Great) founded a new capital city, Pataliputra, and began a conquest of the entire subcontinent. Samudragupta conquered most of India, though in the more distant regions he reinstalled local kings in exchange for their loyalty. Samudragupta was also a great patron of the arts. He was a poet and a musician, and he brought great writers, philosophers, and artists to his court. Unlike the Mauryan kings after Ashoka, who were Buddhists, Samudragupta was a devoted worshipper of the Hindu gods. Nonetheless, he did not reject Buddhism, but invited Buddhists to be part of his court and allowed the religion to spread in his realm. Chandragupta II and the Flourishing of Culture Samudragupta was briefly succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta, whose reign was short. -

Teacher Overview: What Led to the Gupta Golden Age? How Did The

Please Read: We encourage all teachers to modify the materials to meet the needs of their students. To create a version of this document that you can edit: 1. Make sure you are signed into a Google account when you are on the resource. 2. Go to the "File" pull down menu in the upper left hand corner and select "Make a Copy." This will give you a version of the document that you own and can modify. Teacher Overview: What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Unit Essential Question(s): How did classical civilizations gain, consolidate, maintain and lose their power? | Link to Unit Supporting Question(s): ● What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Objective(s): ● Contextualize the Gupta Golden Age. ● Explain the impact of the Gupta Golden Age on India, other regions, and later periods in history. Go directly to student-facing materials! Alignment to State Standards 1. NYS Social Studies Framework: Key Idea Conceptual Understandings Content Specifications 9.3 CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS: 9.3c A period of peace, prosperity, and Students will examine the achievements EXPANSION, ACHIEVEMENT, DECLINE: cultural achievements can be designated of Greece, Gupta, Han Dynasty, Maya, Classical civilizations in Eurasia and as a Golden Age. and Rome to determine if the civilizations Mesoamerica employed a variety of experienced a Golden Age. methods to expand and maintain control over vast territories. They developed lasting cultural achievements. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 18.1 Introduction in Chapter 17, You Learned How India Was Unified for the First Time Under the Mauryan Empire

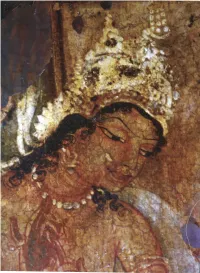

CHAPTER ^ An artist of the Gupta Empire painted this delicate image of the Buddha. The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 18.1 Introduction In Chapter 17, you learned how India was unified for the first time under the Mauryan Empire. In this chapter, you will explore the next great Indian empire, the Gupta Empire. The Guptas were a line of rulers who ruled much of India from 320 to 550 C.E. Many historians have called this period a golden age, a time of great prosperity and achievement. Peaceful times allow people to spend time thinking and being creative. During nonpeaceful times, people are usually too busy keeping themselves alive to spend time on inventions and artwork. For this reason, a number of advances in the arts and sciences came out during the peaceful golden age of the Gupta Empire. These achievements have left a lasting mark on the world. Archeologists have made some amazing discoveries that have helped us learn about the accom- plishments of the Gupta Empire. For example, they have unearthed palm-leaf books that were created about 550 C.E. Palm-leaf books often told religious stories. These stories are just one of many kinds of literature that Indians created under the Guptas. Literature was one of several areas of great accomplishment during India's Golden Age. In this chapter, you'll learn more about the rise of the Gupta Empire. Then Use this illustration of a palm-leaf book as a graphic you'll take a close look at seven organizer to help you learn more about Indian achieve- achievements that came out of ments during the Gupta Empire. -

CLASSICAL INDIA.Pdf

CLASSICAL INDIA Gupta and Mauryan empires 500 BCE-500 CE Recall: INDUS RIVER VALLEY CIVILIZATION ● What do you remember about the Indus River Valley Civilization? ● Lasted about 1000 years, from ~2500 BCE-1500 BCE The Aryans ● The Aryans, an Indo-European group, migrated into India by about 2000 BCE. ● Their sacred literature, the Vedas, are four collections of prayers, hymns, mantras, instructions for performing rituals, as well as spells and incantations. ● The Vedas are the oldest Hindu scriptures. ● Most important Veda is the Rig Veda- contains 1,028 hymns to Aryan gods. ● Passed down orally for years- not written until much later. Vedas The Aryans ● According to the Rig Veda, Ancient Indian society was divided into four groups called varnas. When the Portuguese came to India in the 1500s, they’d call these groups castes: ○ Brahmins- priests and teachers ○ Kshatriyas- warriors and rulers ○ Vaishyas- traders, farmers, and herders ○ Shudras- laborers and peasants The Aryans ● Varnas were initially flexible, then became more structured and based on birth. Later, varna would determine the kind of work people did, whom they could marry, and with whom they could eat. ● Cleanliness and purity became all-important: those considered most impure were called untouchables because of the work they did (collecting trash, cleaning toilets) ● According to a passage in the Rig Veda, the people of the four varnas were created from the body of a single being. The Caste System Aryan Kingdoms Begin ● Aryans extended their settlements east along the Ganges River ● Initially, chiefs were elected by the entire tribe. ● Around 1000 BCE, minor kings who wanted to set up territorial kingdoms arose- they struggled with one another for land and power. -

HT-101 History.Pdf

Directorate of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU JAMMU SELF LEARNING MATERIAL B. A. SEMESTER - I SUBJECT : HISTORY Units I-IV COURSE No. : HT-101 Lesson No. 1-19 Stazin Shakya Course Co-ordinator http:/www.distanceeducation.in Printed and published on behalf of the Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu by the Director, DDE, University of Jammu, Jammu ANCIENT INDIA COURSE No. : HT - 101 Course Contributors : Content Editing and Proof Reading : Dr. Hina S. Abrol Dr. Hina S. Abrol Prof. Neelu Gupta Mr. Kamal Kishore Ms. Jagmeet Kour c Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu, 2019 • All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the DDE, University of Jammu. • The script writer shall be responsible for the lesson/script submitted to the DDE and any plagiarism shall be his/her entire responsibility. Printed at :- Pathania Printers /19/ SYLLABUS B.A. Semester - I Course No. : HT - 101 TITLE : ANCIENT INDIA Unit-I i. Survey of literature - Vedas to Upanishads. ii. Social Life in Early & Later Vedic Age. iii. Economic Life in Early & Later Vedic Age. iv. Religious Life in Early & Later Vedic Age. Unii-II i. Life and Teachings of Mahavira. ii. Development of Jainism after Mahavira. iii. Life and Teachings of Buddha. iv. Development of Buddhism : Four Buddhist Councils and Mahayana Sect. Unit-III i. Origin and Sources of Mauryas. ii. Administration of Mauryas. iii. Kalinga War and Policy of Dhamma Vijaya of Ashoka. iv. Causes of Downfall of the Mauryas. -

Ancient India Teachers Notes

Teachers notes for the Premium TimeMaps Unit Ancient India: The Classical Age 500 BCE to 500 CE Contents Introduction: How to use this unit p.2 Section 1: Whole-class presentation notes p.3 Section 2: Student-based enquiry work p.20 Appendix: TimeMaps articles for further reference p.24 !1 Introduction This Premium TimeMaps unit on Classical India is a sequence of maps offering an overview of the history of the Indian subcontinent between 500 BCE and 500 CE. The sequence can be clicked through to gain a panoramic view of this area of world history. Aims The unit’s aim is to quickly and clearly show the main episodes in the history of the Indian subcontinent in the Classical Period (500 BCE to 500 CE). It does not include the Indus Valley civilization. Nor does it include the long period of Aryan migration into and across northern India which followed. Both these episodes are covered in the Timemaps Premium unit Early Civilizations. Students should finish using this unit with a rounded overview of Classical Indian history. For example, they should that, • In the centuries leading up to 500 BCE great changes were affecting India; • This was resulting in the rise of new religious movements, notably Jainism and Buddhism; • Alexander the Great invaded India, an event which left an enduring legacy in Indian history and culture; • A great empire, the Mauryan empire, rose and fell over a period of a century and a half; • There followed several centuries when India was divided into many states, but that economic, religious and cultural developments continued; • That during these centuries Buddhism spread to other parts of the world; • And that classical Indian civilization reached its peak at a time when a second great empire, the Gupta empire, dominated northern India. -

First Empires of India

173-176-0207s1 10/11/02 3:42 PM Page 173 TERMS & NAMES 1 • Mauryan Empire First Empires • Asoka •religious toleration •Tamil of India • Gupta Empire • patriarchal MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW • matriarchal The Mauryas and the Guptas The diversity of peoples, cultures, be- established Indian empires, but neither liefs, and languages in India continues unified India permanently. to pose challenges to Indian unity today. SETTING THE STAGE By 600 B.C., almost 1,000 years after the Aryan migrations, many small kingdoms were scattered throughout India. In 326 B.C., Alexander the Great brought the Indus Valley in the northwest under Greek control—but left the region almost immediately. Soon after, a great Indian military leader, Chandragupta Maurya (CHUHN•druh•GUP•tuh MAH•oor•yuh), seized power for himself. Background Chandragupta Maurya Builds an Empire Chandragupta Chandragupta Maurya may have been born in the powerful kingdom of Magadha. may have been Centered on the lower Ganges River, the kingdom had been ruled for centuries by the a younger son of the Nanda king. Nanda family. Chandragupta gathered an army, killed the Nanda king, and in about 321 B.C. claimed the throne. This began the Mauryan Empire. Chandragupta Unifies North India Chandragupta moved northwest, seizing all the land from Magadha to the Indus. Around 305 B.C., Chandragupta began to battle Seleucus I, one of Alexander the Great’s generals. Seleucus had inherited the eastern part of Alexander’s empire. He wanted to reestablish Greek control over the Indus Valley. After several years of fighting, however, Chandragupta defeated Seleucus, who gave up some of his terri- SPOTLIGHTON tory to Chandragupta.