An Anthropological Study of Smes in Manchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law, Practice, Remedies, and Oversight

___________________________ SUMMARY OF U.S. FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE LAW, PRACTICE, REMEDIES, AND OVERSIGHT ASHLEY GORSKI AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION AUGUST 30, 2018 _________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS QUALIFICATIONS AS AN EXPERT ............................................................................................. iii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. U.S. Surveillance Law and Practice ................................................................................... 2 A. Legal Framework ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Presidential Power to Conduct Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ....................... 3 2. The Expansion of U.S. Government Surveillance .................................................. 4 B. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 ..................................................... 5 1. Traditional FISA: Individual Orders ..................................................................... 6 2. Bulk Searches Under Traditional FISA ................................................................. 7 C. Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act ........................................... 8 D. How The U.S. Government Uses Section 702 in Practice ......................................... 12 1. Data Collection: PRISM and Upstream Surveillance ........................................ -

Limitless Surveillance at the Fda: Pro- Tecting the Rights of Federal Whistle- Blowers

LIMITLESS SURVEILLANCE AT THE FDA: PRO- TECTING THE RIGHTS OF FEDERAL WHISTLE- BLOWERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 26, 2014 Serial No. 113–88 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–176 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 11:40 Mar 31, 2014 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\87176.TXT APRIL COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM DARRELL E. ISSA, California, Chairman JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland, Ranking MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio Minority Member JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM JORDAN, Ohio Columbia JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts TIM WALBERG, Michigan WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan JIM COOPER, Tennessee PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania JACKIE SPEIER, California SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee MATTHEW A. CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania TREY GOWDY, South Carolina TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois DOC HASTINGS, Washington DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois CYNTHIA M. LUMMIS, Wyoming PETER WELCH, Vermont ROB WOODALL, Georgia TONY CARDENAS, California THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky STEVEN A. -

Congressional Correspondence

People Record 7006012 for The Honorable Peter T. King Help # ID Opened � WF Code Assigned To Template Due Date Priority Status 1 885995 11/3/2010 ESLIAISON4 (b)(6) ESEC Workflow 11/10/2010 9 CLOSED FEMA Draft Due to ESEC: 11/10/2010 ESEC Case Number (ESEC Use Only): 10-9970 To: Secretary Document Date: 10/25/2010 *Received Date: 11/03/2010 *Attachment: Yes Significant Correspondence (ESEC Use Only): Yes *Summary of Document: Write in support of the application submitted by the (b)(4) for $7,710,089 under the Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response grant program. *Category: Congressional *Type: Congressional - Substantive Issue *Action to be Taken: Assistant Secretary OLA Signature Status: Action: *Lead Component: FEMA *Signed By (ESEC Use Only): Component Reply Direct and cc: *Date Response Signed: 11/02/2010 Action Completed: 11/04/2010 *Complete on Time: Yes Attachments: 10-9970rcuri 10.25.10.pdf Roles: The Honorable Michael Arcuri(Primary, Sender), The Honorable Timothy H. Bishop(Sender) 2 884816 10/22/2010 ESLIAISON4 (b)(6) ESEC Workflow 11/5/2010 9 OPEN FEMA Reply Direct Final Due Date: 11/05/2010 ESEC Case Number (ESEC Use Only): 10-9776 To: Secretary Mode: Fax Document Date: 10/20/2010 *Received Date: 10/22/2010 *Attachment: Yes Significant Correspondence (ESEC Use Only): No *Summary of Document: Requests an Urban Area Security Initiative designation for seven southern San Joaquin Valley Counties. *Category: Congressional *Type: Congressional - Substantive Issue *Action to be Taken: Component Reply Direct and Cc: Status: -

GLOBAL CENSORSHIP Shifting Modes, Persisting Paradigms

ACCESS TO KNOWLEDGE RESEARCH GLOBAL CENSORSHIP Shifting Modes, Persisting Paradigms edited by Pranesh Prakash Nagla Rizk Carlos Affonso Souza GLOBAL CENSORSHIP Shifting Modes, Persisting Paradigms edited by Pranesh Pra ash Nag!a Ri" Car!os Affonso So$"a ACCESS %O KNO'LE(GE RESEARCH SERIES COPYRIGHT PAGE © 2015 Information Society Project, Yale Law School; Access to Knowle !e for "e#elo$ment %entre, American Uni#ersity, %airo; an Instituto de Technolo!ia & Socie a e do Rio+ (his wor, is $'-lishe s'-ject to a %reati#e %ommons Attri-'tion./on%ommercial 0%%.1Y./%2 3+0 In. ternational P'-lic Licence+ %o$yri!ht in each cha$ter of this -oo, -elon!s to its res$ecti#e a'thor0s2+ Yo' are enco'ra!e to re$ro 'ce, share, an a a$t this wor,, in whole or in part, incl' in! in the form of creat . in! translations, as lon! as yo' attri-'te the wor, an the a$$ro$riate a'thor0s2, or, if for the whole -oo,, the e itors+ Te4t of the licence is a#aila-le at <https677creati#ecommons+or!7licenses7-y.nc73+07le!alco e8+ 9or $ermission to $'-lish commercial #ersions of s'ch cha$ter on a stan .alone -asis, $lease contact the a'thor, or the Information Society Project at Yale Law School for assistance in contactin! the a'thor+ 9ront co#er ima!e6 :"oc'ments sei;e from the U+S+ <m-assy in (ehran=, a $'-lic omain wor, create by em$loyees of the Central Intelli!ence A!ency / em-assy of the &nite States of America in Tehran, de$ict. -

Lab Activity and Assignment #2

Lab Activity and Assignment #2 1 Introduction You just got an internship at Netfliz, a streaming video company. Great! Your first assignment is to create an application that helps the users to get facts about their streaming videos. The company works with TV Series and also Movies. Your app shall display simple dialog boxes and help the user to make the choice of what to see. An example of such navigation is shown below: Path #1: Customer wants to see facts about a movie: >> >> Path #2: Customer wants to see facts about a TV Series: >> >> >> >> Your app shall read the facts about a Movie or a TV Show from text files (in some other course you will learn how to retrieve this information from a database). They are provided at the end of this document. As part of your lab, you should be creating all the classes up to Section 3 (inclusive). As part of your lab you should be creating the main Netfliz App and making sure that your code does as shown in the figures above. The Assignment is due on March 8th. By doing this activity, you should be practicing the concept and application of the following Java OOP concepts Class Fields Class Methods Getter methods Setter methods encapsulation Lists String class Split methods Reading text Files Scanner class toString method Override superclass methods Scanner Class JOptionPane Super-class sub-class Inheritance polymorphism Class Object Class Private methods Public methods FOR loops WHILE Loops Aggregation Constructors Extending Super StringBuilder Variables IF statements User Input And much more.. -

Patrol Guide § 212-72

EXHIBIT K AOR307 An Investigation of NYPD’s Compliance with Rules Governing Investigations of Political Activity New York City Department of Investigation Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD (OIG-NYPD) Mark G. Peters Commissioner Philip K. Eure Inspector General for the NYPD August 23, 2016 AOR308 AN INVESTIGATION OF NYPD’S COMPLIANCE WITH RULES GOVERNING AUGUST 2016 INVESTIGATIONS OF POLITICAL ACTIVITY Table of Contents Overview ............................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 11 I. NYPD Investigations of Political Activity: Handschu and Patrol Guide § 212-72 ....... 11 II. OIG-NYPD Investigation .............................................................................................. 12 Methodology and Access ..................................................................................................... 13 I. Treatment of Sensitive Information ............................................................................ 13 II. Compliance Criteria ..................................................................................................... 13 III. Scope and Sampling .................................................................................................... 14 -

The Electrical Transformation of the Public Sphere: Home Video, the Family, and the Limits of Privacy in the Digital Age

THE ELECTRICAL TRANSFORMATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE: HOME VIDEO, THE FAMILY, AND THE LIMITS OF PRIVACY IN THE DIGITAL AGE By Adam Capitanio A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY American Studies 2012 ABSTRACT THE ELECTRICAL TRANSFORMATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE: HOME VIDEO, THE FAMILY, AND THE LIMITS OF PRIVACY IN THE DIGITAL AGE By Adam Capitanio One of the constituent features of the digital age has been the redrawing of the line between private and public. Millions of social media users willingly discuss intimate behavior and post private photographs and videos on the internet. Meanwhile, state and corporate bodies routinely violate individual privacy in the name of security and sophisticated marketing techniques. While these occurrences represent something new and different, they are unsurprising given the history of home and amateur media. In this dissertation, I argue that contemporary shifts in the nature of the public/private divide have historical roots in the aesthetics and style found in home movies and videos. In other words, long before Facebook and YouTube enabled users to publicly document their private lives, home movies and videos generated patterns of representation that were already shifting the unstable constitution of the “private” and the “public” spheres. Using critical theory and archival research, I demonstrate how home moviemakers represented their families and experiences in communal and liminal spaces, expanding the meaning of “home.” When video become the predominant medium for domestic usage, home mode artifacts became imbricated with television, granting them a form of phantasmagoric publicity that found fulfillment in the digital era. -

Review of Pilot

COMING HOME: A STUDY OF VALUES CHANGE AMONG CHINESE POSTGRADUATES AND VISITING SCHOLARS WHO ENCOUNTERED CHRISTIANITY IN THE U.K. ANDREA DEBORAH CLAIRE DICKSON, BA, MIS, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY 2013 Abstract This thesis examines changes in core values held by postgraduate students and visiting scholars from China who professed belief in Christianity while studying in UK universities. It is the first study to ascertain whether changes remain after return to China. Employing a theoretical framework constructed from work by James Fowler, Charles Taylor, Yuting Wang and Fenggang Yang, it identifies both factors contributing to initial change in the UK and factors contributing to sustained change after return to China. It shows that lasting values change occurred. As a consequence, tensions were experienced at work, socially and in church. However, these were outweighed by benefits, including inner security, particularly after a distressed childhood. Benefits were also experienced in personal relationships and in belonging in a new community, the Church. This was a qualitative, interpretive study employing ethnographic interviews with nineteen people, from eleven British universities, in seven Chinese cities. It was based on the hypotheses that Christian conversion leads to change in values and that evidence for values can be found in responses to major decisions and dilemmas, in saddest and happiest memories and in relationships. Conducted against a backdrop of transnational movement of people and ideas, including a recent increase in mainland Chinese studying abroad which has led to more Chinese in British churches, it contributes new insights into both the contents of sustained Christian conversion amongst Chinese abroad who have since returned to China and factors contributing to it. -

Electronic Surveillance in Workplaces and Their Legitimate Usage to Provide Transparency and Accountability Towards Employees

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Electronic surveillance in workplaces and their legitimate usage to provide transparency and accountability towards employees 1Gursimran Singh, 2Dr. Payal Bassi 1Research Scholar, 2Professor, 1 Department of Commerce and Management 1Regional Institute of Management and Technology, Mandi Gobindgarh, India Abstract: Companies used surveillance software’s, CCTV cameras to watch their employees, monitoring their e-mails or the websites content they visit. Sometimes managers used surveillance to provide protection of their companies from legal acquaintances that originates against the wrong doing behavior of their employees such as download of pornography material and provoke able e-mails or messages to other individuals and to provide protection against the inappropriate exposure of exclusive or confidential information on the internet. As the reasons of employers behind these processes can be valid, there are conflicting thoughts of the usage of this technology among the employees. This paper discusses the latest surveillance measures, technologies used by the employer, lawful disputes that can arise from surveillance as well as consequences or problems originate for the management. This paper also discusses some questions about the right of usage of internet or e-mails in the corporations for the personnel motives of the employees and to what extent their can use their right. To what extent the managers or companies lawfully monitor the workplaces or employees behavior on the internet. And about the employees expectations regarding the surveillance used in order to protect their online privacy and the legal options company have provided for them. The paper expresses the ways for further research in surveillance of employees and a more detailed reasoning in improving lawful and policy-making can be analyzed further. -

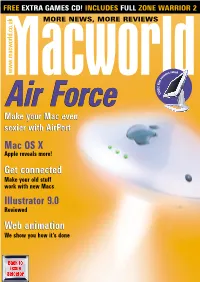

MACWORLD JULY 2000 AIRPORT • FLAT PANELS • MAC CONNECTIVITY • MAC OS X NEWS • ILLUSTRATOR 9 • MICROSOFT INTERVIEW Read Me First MACWORLD Simon Jary, Editor-In-Chief

FREE EXTRA GAMES CD! INCLUDES FULL ZONE WARRIOR 2 MACWORLD MORE NEWS, MORE REVIEWS JULY 2000 JULY AIRPORT • FLAT PANELS • AIRPORT PANELS MAC• FLAT CONNECTIVITY • MAC OS X 9 NEWS • • MICROSOFT ILLUSTRATOR INTERVIEW Macworldwww.macworld.co.uk rated s en re c s t a l F … g ! L n i O d O C e e p s f a Air Force aster than Make your Mac even sexier with AirPort Mac OS X Apple reveals more! Get connected Make your old stuff work with new Macs Illustrator 9.0 Reviewed Web animation We show you how it’s done read me first MACWORLD Simon Jary, editor-in-chief eaders may be alarmed at our news (page 42) that sales of Apple’s newer than CD. But the ability to burn phenomenally successful iMac computer seem to have slumped. your own CDs is functionally more Apple’s Airport R I’m sure Apple is upset, as the iMac is its flagship product – wooing advanced. And, just as consumers want woozy Windows users and seducing computer novices with its retro-cool bigger screens, they look for functionality design, see-through plastics and nifty DV features. ahead of technology. There aren’t that many wireless technology The iMac is the key to Apple’s recovery from the dire state the company DVD titles out there, aside from DVD-Video 86 found itself in after years of complacency and missed business opportunities. movies – and who’d watch Gladiator on an iMac Just look at the numbers… According to the latest stats from analysts PC Data, when you’ve got a 29-inch widescreen telly in front of your sofa? lets you throw off the yoke Apple is the number-four PC vendor with 9.6 per cent of the market – behind Apple ignores PC Data’s stats because it ignores its direct sales from eMachines (13%), Hewlett-Packard (32%) and Compaq (34%). -

2018-2019 Budget.Pdf

2018-2019 BUDGET TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Trustees and Superintendent's Cabinet ……………………………………………….………….…..…...…………...……………1 Administrative Team Members (A-Team) …...…..…….……………………………….…….…….. 2 Business Services Staff …...…………………………...……………..…….……………………………….…….……..3 District Advisors …...…………………………...……………..…….……………………………….…….……..4 District Mission Statement, Vision, & Goals……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….5 District Facilities……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….6 Facility Map……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….7 Financial Account Code Structure……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….8 Fund Codes……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….10 Function Codes……..…………….……………….……………………………..……………………..…………..12 Organization Codes………………..…………………………………………..………………………..……….14 Program Intent Codes …………..……………………………….……………………...……………..16 Budget Manager Codes………………..…………………………………………..………………………..……….17 Function/Program Intent Code Matrix……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….19 Revenue Object Codes ……………….………………………………………………...……………………………….20 Expenditure Object Codes ……………….………………………………………………...……………………………….21 Budget Overview……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….24 Director Budget Planning……………………...…….………………………………………….……………………..………….25 Campus Budget Planning………………..…………………………………………..………………………..……….26 Technology Budget Planning………………..…………………………………………..………………………..……….27 Supplemental Budget Planning………………..…………………………………………..………………………..……….28 Special Populations………………..…………………………………………..………………………..……….29 -

2018 NSCP National Conference Agenda

2018 NSCP National Conference Agenda MONDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2018 8:30 am – 9:30 am General Session with Keynote Speaker – Rashmi Airan 9:30 am – 9:50 am Break 9:50 am – 11:05 am Session 1 (75 minutes) 1a. IA/IC/PF Regulatory Review Panel (OPEN) Hear directly from SEC and NFA regulators to help compliance professionals understand and manage the regulatory landscape and the impact to your business, with a chance to submit questions. This session is open to regulators and members of the press. Advanced Preparation: None Pre-requisites for participation: No prerequisites are required Learning Objectives: • Learn what changes have occurred at the SEC and NFA under the current administration in Washington. • Understand what the SEC and NFA priorities are going forward and learn more about how the SEC/NFA intends to analyze and evaluate big data based on firm regulatory filings such as Form ADV, Form PF, Form CPO-PQR, etc. • Discuss where the SEC and NFA stand on new rules and rule proposals including: report modernization, liquidity, business continuity, and derivatives, recent no action letters, alerts and guidance and recent enforcement actions. • Assess SEC/NFA priorities and related to cybersecurity, breaches to privacy, and standardizing fee and other disclosures to further enhance your oversight program. 1b. ALL – Best Practices for Managing a Global Compliance Program (Advanced) Many firms look to expand their services overseas and can run afoul of foreign regulatory requirements. This session is intended to get you familiar with some of the more common compliance requirements and practices to protect your global brand.