Passions, Doux Commerce, Interest Properly Understood: from Adam Smith to Alexis De Tocqueville and Beyond Andreas Hess [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restless Liberalism of Alexis De Tocqueville

FILOZOFIA ___________________________________________________________________________Roč. 72, 2017, č. 9 THE RESTLESS LIBERALISM OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE JAKUB TLOLKA, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK TLOLKA, J.: The Restless Liberalism of Alexis de Tocqueville FILOZOFIA, 72, No. 9, 2017, pp. 736-747 This essay attempts to contextualise the purported novelty of Alexis de Tocqueville’s particular brand of liberalism. It regards the author not as an heir or precursor to any given political tradition, but rather as a compelled syncretist whose primary philosophical concern was the moral significance of the democratic age. It suggests that Tocqueville devised his ‘new political science’ with a keen view to the existential implications of modernity. In order to support that suggestion, the essay explores the genealogy of Tocqueville’s moral and political thought and draws a relation between his analysis of democracy and his personal experience of modernity. Keywords: A. de Tocqueville – Modernity – Liberalism – Inquiétude – Religion Introduction. Relatively few authors in the history of political thought have produced an intellectual legacy of such overarching resonance as Alexis de Tocqueville. Even fewer, perhaps, have so persistently eluded ordinary analytical and exegetical frameworks, presenting to each astute observer a face so nuanced as to preclude serious interpretive consensus. As writes Lakoff (Lakoff 1998), ‘disagreement over textual interpretation in the study of political thought is not uncommon’. However, ‘it usually arises around those who left writings of a patently divergent character’ (p. 437). When we thus consider the ‘extraordinarily coherent and consistent nature’ of Alexis de Tocqueville’s political philosophy, it appears somewhat odd that the academic consensus surrounding that author relates almost exclusively to the grandeur of his intellectual achievement (Lukacs 1959, 6). -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

Alexis De Tocqueville Chronicler of the American Democratic Experiment

Economic Insights FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 Alexis de Tocqueville Chronicler of the American Democratic Experiment The Early Years bring Tocqueville fame and honors. In Born in Paris in 1805, Alexis- 1833, about a year after Tocqueville We are pleased to add this piece on Charles-Henri Clérel de Tocqueville returned to France, the report on Alexis de Tocqueville to our series of profiles entered the world in the early and most American prisons, The U.S. Penitentiary powerful days of Napoleon’s empire. System and Its Application in France, that began with Frédéric Bastiat and Friedrich His parents were of the nobility and was published. von Hayek. Both Bastiat and Hayek were had taken the historical family name of Things in France changed for Beau- strong and influential proponents of indi- Tocqueville, which dated from the mont and Tocqueville upon their return early 17th century and was a region after 10 months in America. Both men vidual liberty and free enterprise. While they of France known previously as the left the judiciary. Beaumont was offi- approached those topics from a theoretical Leverrier fief. cially let go, and Tocqueville resigned perspective, Tocqueville’s views on early Tocqueville’s father supported the in sympathetic protest. Tocqueville then French monarchy and played no seri- had ample time to work on his master- American and French democracy were based ous role in public affairs until after piece, Democracy in America. Volume 1 on his keen personal observations and his- Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, was published in 1835. -

The Roots of Modern Conservative Thought from Burke to Kirk Edwin J

No. 19 The Roots of Modern Conservative Thought from Burke to Kirk Edwin J. Feulner, Ph.D. merica is the most successful and enduring exper- who nurtured the roots with their law and social Aiment in democracy in human history. It has sur- awareness. vived foreign invasion and terrorist attacks, world The roots intertwined with “the Christian under- wars and a civil war, a great depression and not so standing of human duties and human hopes, of man small recessions, presidential assassinations and scan- redeemed,” and were then joined by medieval custom, dals, an adversary culture and even the mass media. It learning, and valor.2 is the most powerful, prosperous, and envied nation The roots were enriched, finally, by two great exper- in the world. iments in law and liberty that occurred in London, What is the source of America’s remarkable suc- home of the British Parliament, and in Philadelphia, cess? Its abundant natural resources? Its hardworking, birthplace of the Declaration of Independence and the entrepreneurial, can-do people? Its fortuitous loca- U.S. Constitution. Kirk’s analysis thus might be called tion midway between Europe and Asia? Its resilient a tale of five cities—Jerusalem, Athens, Rome, London, national will? and Philadelphia. Why do we Americans enjoy freedom, opportunity, Much more could be said about the philosophi- and prosperity as no other people in history have? cal contributions of the Jews, the Greeks, and the In The Roots of American Order, the historian Rus- Romans to the American experience, but I will limit sell Kirk provides a persuasive answer: America is not myself to discuss the roots of modern conservative only the land of the free and the home of the brave, but thought that undergird our nation and which for a place of ordered liberty. -

Moral Views of Market Society

ANRV316-SO33-14 ARI 31 May 2007 12:29 Moral Views of Market Society Marion Fourcade1 and Kieran Healy2 1Department of Sociology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-1980; email: [email protected] 2Department of Sociology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007. 33:285–311 Key Words First published online as a Review in Advance on markets, capitalism, moral order, culture, performativity, April 5, 2007 governmentality The Annual Review of Sociology is online at http://soc.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: Upon what kind of moral order does capitalism rest? Conversely, by University of California - Berkeley on 08/30/07. For personal use only. 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131642 does the market give rise to a distinctive set of beliefs, habits, and Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007.33:285-311. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org Copyright c 2007 by Annual Reviews. social bonds? These questions are certainly as old as social science All rights reserved itself. In this review, we evaluate how today’s scholarship approaches 0360-0572/07/0811-0285$20.00 the relationship between markets and the moral order. We begin with Hirschman’s characterization of the three rival views of the market as civilizing, destructive, or feeble in its effects on society. We review recent work at the intersection of sociology, economics, and political economy and show that these views persist both as theories of market society and moral arguments about it. We then argue that a fourth view, which we call moralized markets, has become increasingly prominent in economic sociology. -

The Uses of Alexis De Tocqueville's Writings in US Judicial Opinions

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Book Sections Faculty Scholarship 2008 A Man for All Reasons: The sesU of Alexis de Tocqueville's Writings in U.S. Judicial Opinions Christine Corcos Louisiana State University Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/book_sections Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Corcos, Christine, "A Man for All Reasons: The sU es of Alexis de Tocqueville's Writings in U.S. Judicial Opinions" (2008). Book Sections. 46. http://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/book_sections/46 This Book Section is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Sections by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Man for All Reasons: The Uses of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Writing in U S. Judicial Opinions ∗ Christine A. Corcos Before Saul Litvinoff appeared on U. S. shores, another aristocratic comparativist, Alexis de Tocqueville, came to cast a critical yet affectionate eye on this republic. Since I am fond of both of these thinkers, I offer this overview of the judicial uses of the writings of the earlier scholar in appreciation of the later one. I. Introduction The United States has never been given to particular adoration of foreign observers of its mores, who quite often turn out to be critics rather than admirers. Nevertheless, one of its favorite visitors 1 since his one and only appearance on the scene in 1831-1832 2 is the 25-year-old magistrate Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859), sent by his government to study penal reform in the new republic. -

Some Remarks on John Stuart Mill's Account of Tocqueville's

SOME REMARKS ON JOHN STUART MILL’S ACCOUNT OF TOCQUEVILLE’S CONCERN WITH THE MASSES IN DEMOCRATIC SOCIETIES ÁTILA AMARAL BRILHANTE E FRANCISCO JOSÉ SALES ROCHA1 (UFC / Brasil) RESUMO Este artigo mostra que John Stuart Mill e Alexis de Tocqueville defenderam a existência de uma cultu- ra cívica capaz de contribuir para o florescimento da liberdade, da diversidade e impedir as massas de adquirirem um poder impossível de ser controlado. O argumento principal é que, no início da década de 1840, John Stuart Mill incorporou ao seu pensamento político a ideia de Alexis de Tocqueville de que, para que a democracia tenha um adequado funcionamento, o poder das massas deve ser contraba- lançado. Inicialmente, John Stuart Mill tentou encontrar um poder na sociedade para contrabalançar o poder das massas, mas depois ele passou a defender um novo formato para as instituições com o obje- tivo de garantir a presença das minorias educadas no parlamento e, por meio disto, estabelecer o con- fronto de ideias que ele julgava tão necessário para prevenir a tirania das massas. No intento de evitar os excessos da democracia, John Stuart Mill deu maior importância à construção das instituições polí- ticas, enquanto Alexis de Tocqueville enfatizou mais o papel da participação na política local. Apesar disto, a dívida do primeiro para com o pensamento político do segundo é imensa. Palavras-chave: O poder das massas. Controlabilidade. Democracia. J. S. Mill. A. de Tocqueville. ABSTRACT This article shows that both J. S. Mill and Tocqueville favoured a civic culture that supported liberty, diversity and prevented the uncontrolled power of the masses. -

Prospects for Democracy: Individualism/Collectivism As Sources of Association/Community

CHAPTER THREE PROSPECTS FOR DEMOCRACY: INDIVIDUALISM/COLLECTIVISM AS SOURCES OF ASSOCIATION/COMMUNITY It is a pity that the Federalist Papers, George Washington’s last Address to the Nation, and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (Tocqueville 2000) are considered models of political analysis, while starting somewhere in the last half of the 19th century Americans got used to politicians and their advisors spoon-feeding us with pablum instead of analysis. Woodrow Wilson had some responsibility for the failures of democracy in the generation aft er World War I, the rstfi of our many Wars to End All Wars. By telling how easy it is to have a Democracy, he got the Germans to surrender easily enough, without us having to cross the Rhine, then for years aft erward they would elab- orate on “stab in the back” doctrines once they decided they had been tricked and maybe they shouldn’t have surrendered so easily, partly because they discovered that democracy doesn’t really come that easy. It was to a large extent the good sense of European leadership aft er World War II that got at least Western and now Eastern Europe to cooperate, fi nally. We were gracious with our Marshall Plan to rebuild the European economy, and created markets for ourselves at the same time, but our political advice was they thought excessively simple, as it has been throughout the last century. It is the kind which President George W. Bush exemplifi ed with his “Th ey hate us for our freedom” explanation of why so much of the rest of the world is not like us; if only it were so simple life would be a lot easier. -

The Abolition of Emerson: the Secularization of America’S Poet-Priest and the New Social Tyranny It Signals

THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Washington, DC February 1, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Justin James Pinkerman All Rights Reserved ii THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Dr. Richard Boyd, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Motivated by the present climate of polarization in US public life, this project examines factional discord as a threat to the health of a democratic-republic. Specifically, it addresses the problem of social tyranny, whereby prevailing cultural-political groups seek to establish their opinions/sentiments as sacrosanct and to immunize them from criticism by inflicting non-legal penalties on dissenters. Having theorized the complexion of factionalism in American democracy, I then recommend the political thought of Ralph Waldo Emerson as containing intellectual and moral insights beneficial to the counteraction of social tyranny. In doing so, I directly challenge two leading interpretations of Emerson, by Richard Rorty and George Kateb, both of which filter his thought through Friedrich Nietzsche and Walt Whitman and assimilate him to a secular-progressive outlook. I argue that Rorty and Kateb’s political theories undercut Emerson’s theory of self-reliance by rejecting his ethic of humility and betraying his classically liberal disposition, thereby squandering a valuable resource to equip individuals both to refrain from and resist social tyranny. -

Kant Y La Tesis Acerca Del Doux Commerce. Sobre La Interconexión Del Espíritu Comercial, El Derecho Y La Paz En La Filosofía De La Historia De Kant1

CON-TEXTOS KANTIANOS. International Journal of Philosophy N.o 7, Junio 2018, pp. 375-385 ISSN: 2386-7655 Doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1299349 Kant y la tesis acerca del doux commerce. Sobre la interconexión del espíritu comercial, el derecho y la paz en la filosofía de la historia de Kant1 Kant and the thesis of le doux commerce. On the relation of the spirit of commerce, law, and peace in Kant’s philosophy of history DIETER HÜNING2 Universidad de Tréveris, Alemania Resumen Este artículo se centra en las apologías de Kant acerca de la sociedad comercial en su texto de Hacia la paz perpetua. Dichas apologías, que pueden resumirse bajo el título "le doux commerce", se difundieron en el siglo XVIII. Muchos filósofos e historiadores, como Montesquieu, Hume, Voltaire y Ferguson, formaron parte de este grupo. La cuestión decisiva para Kant fue combinar tal apología con su concepción teleológica de la historia, que desarrolló en su Ideas para una historia universal en clave cosmopolita. Palabras clave Apología de la sociedad comercial, paz perpetua, concepción teleológica de la historia, doux commerce 1 El presente texto ofrece una versión reducida del artículo aparecido inicialmente en alemán: "Es ist der Handelsgeist, der mit dem Kriege nicht bestehen kann". – Handel, Recht und Frieden in Kants Geschichtsphilosophie, en Olaf Asbach (coord.): Der moderne Staat und ‚le doux commerce’. Politik, Ökonomie und internationales System im politischen Denken der Aufklärung, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2014, pp. 251-274 [= Staatsverständnisse, Editado por Rüdiger Voigt, Bd. 68]. Agradezco al Prof. Dr. Oscar Cubo (Universitat de València) por la traducción de este texto al castellano. -

The Constitution and the Other Constitution

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 10 (2001-2002) Issue 2 Article 3 February 2002 The Constitution and The Other Constitution Michael Kent Curtis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Michael Kent Curtis, The Constitution and The Other Constitution, 10 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 359 (2002), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol10/iss2/3 Copyright c 2002 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE CONSTITUTION AND THE OTHER CONSTITUTION Michael Kent Curtis* In this article,Professor Michael Kent Curtisexamines how laws thatshape the distributionof wealth intersect with and affectpopularsovereigntyandfree speech and press. He presents this discussion in the context of the effect of the Other Constitutionon The Constitution. ProfessorCurtis begins by taking a close-up look at the current campaignfinance system and the concentrationof media ownership in a few corporate bodies and argues that both affect the way in which various politicalissues arepresented to the public, ifat all. ProfessorCurtis continues by talking about the origins of our constitutional ideals ofpopular sovereignty and free speech andpressand how the centralizationof economic power has limited the full expression of these most basic of democratic values throughout American history. Next, he analyzes the Supreme Court's decision in Buckley v. Valeo, the controlling precedent with respect to the constitutionality of limitations on campaign contributions. Finally, ProfessorCurtis concludes that the effect of the Other Constitution on The Constitution requires a Television Tea Party and a government role in the financingofpolitical campaigns. -

Lesson Plan Template

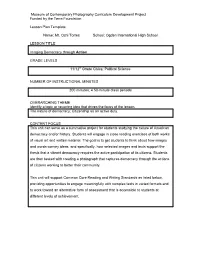

Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation Lesson Plan Template Name: Mr. Ozni Torres School: Ogden International High School LESSON TITLE Imaging Democracy through Action GRADE LEVELS 11/12th Grade Civics; Political Science NUMBER OF INSTRUCTIONAL MINUTES 200 minutes; 4 50-minute class periods OVERARCHING THEME Identify a topic or recurring idea that drives the focus of the lesson. The nature of democracy; Citizenship as an active duty. CONTENT FOCUS This unit can serve as a summative project for students studying the nature of American democracy and/or history. Students will engage in close reading exercises of both works of visual art and written material. The goal is to get students to think about how images and words convey ideas, and specifically, how selected images and texts support the thesis that a vibrant democracy requires the active participation of its citizens. Students are then tasked with creating a photograph that captures democracy through the actions of citizens working to better their community. This unit will support Common Core Reading and Writing Standards as listed below, providing opportunities to engage meaningfully with complex texts in varied formats and to work toward an alternative form of assessment that is accessible to students at different levels of achievement. Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation ART ANALYSIS List the names of artist(s) and titles of their artwork that students will do close reading exercises on. Artist Work of Art John Trumbull 12’ X 18’ 1818 Rotunda; U.S. Capitol D eclaration of Independence Paul Shambroom 2’9” X 5’6” 1999 Museum of Contemporary Photography Markl e, IN (pop.