Identifying Genetic Variants and Pathways Associated with Extreme Levels of Fetal Hemoglobin in Sickle Cell Disease in Tanzania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypoxia-Induced Alpha-Globin Expression in Syncytiotrophoblasts Mimics the Pattern Observed in Preeclamptic Placentas

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Hypoxia-Induced Alpha-Globin Expression in Syncytiotrophoblasts Mimics the Pattern Observed in Preeclamptic Placentas Zahra Masoumi 1,* , Lena Erlandsson 1, Eva Hansson 1, Mattias Magnusson 2, Eva Mezey 3 and Stefan R. Hansson 1,4 1 Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lund University, SE-22184 Lund, Sweden; [email protected] (L.E.); [email protected] (E.H.); [email protected] (S.R.H.) 2 Department of Molecular Medicine and Gene Therapy, Lund University, SE-22184 Lund, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Adult Stem Cell Section, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; [email protected] 4 Skåne University Hospital, SE-22184 Lund, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Preeclampsia (PE) is a pregnancy disorder associated with placental dysfunction and elevated fetal hemoglobin (HbF). Early in pregnancy the placenta harbors hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and is an extramedullary source of erythropoiesis. However, globin ex- pression is not unique to erythroid cells and can be triggered by hypoxia. To investigate the role of the placenta in increasing globin levels previously reported in PE, flow cytometry, histological and Citation: Masoumi, Z.; Erlandsson, immunostaining and in situ analyses were used on placenta samples and ex vivo explant cultures. L.; Hansson, E.; Magnusson, M.; Our results indicated that in PE pregnancies, placental HSPC homing and erythropoiesis were not Mezey, E.; Hansson, S.R. affected. Non-erythroid alpha-globin mRNA and protein, but not gamma-globin, were detected in Hypoxia-Induced Alpha-Globin Expression in Syncytiotrophoblasts syncytiotrophoblasts and stroma of PE placenta samples. -

Serum Albumin OS=Homo Sapiens

Protein Name Cluster of Glial fibrillary acidic protein OS=Homo sapiens GN=GFAP PE=1 SV=1 (P14136) Serum albumin OS=Homo sapiens GN=ALB PE=1 SV=2 Cluster of Isoform 3 of Plectin OS=Homo sapiens GN=PLEC (Q15149-3) Cluster of Hemoglobin subunit beta OS=Homo sapiens GN=HBB PE=1 SV=2 (P68871) Vimentin OS=Homo sapiens GN=VIM PE=1 SV=4 Cluster of Tubulin beta-3 chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=TUBB3 PE=1 SV=2 (Q13509) Cluster of Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 (P60709) Cluster of Tubulin alpha-1B chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=TUBA1B PE=1 SV=1 (P68363) Cluster of Isoform 2 of Spectrin alpha chain, non-erythrocytic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=SPTAN1 (Q13813-2) Hemoglobin subunit alpha OS=Homo sapiens GN=HBA1 PE=1 SV=2 Cluster of Spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=SPTBN1 PE=1 SV=2 (Q01082) Cluster of Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PKM PE=1 SV=4 (P14618) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 Clathrin heavy chain 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=CLTC PE=1 SV=5 Filamin-A OS=Homo sapiens GN=FLNA PE=1 SV=4 Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=DYNC1H1 PE=1 SV=5 Cluster of ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 2 (+) polypeptide OS=Homo sapiens GN=ATP1A2 PE=3 SV=1 (B1AKY9) Fibrinogen beta chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGB PE=1 SV=2 Fibrinogen alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGA PE=1 SV=2 Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=DPYSL2 PE=1 SV=1 Cluster of Alpha-actinin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTN1 PE=1 SV=2 (P12814) 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial OS=Homo -

Adult, Embryonic and Fetal Hemoglobin Are Expressed in Human Glioblastoma Cells

514 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 44: 514-520, 2014 Adult, embryonic and fetal hemoglobin are expressed in human glioblastoma cells MARWAN EMARA1,2, A. ROBERT TURNER1 and JOAN ALLALUNIS-TURNER1 1Department of Oncology, University of Alberta and Alberta Health Services, Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton, AB T6G 1Z2, Canada; 2Center for Aging and Associated Diseases, Zewail City of Science and Technology, Cairo, Egypt Received September 7, 2013; Accepted October 7, 2013 DOI: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2186 Abstract. Hemoglobin is a hemoprotein, produced mainly in Introduction erythrocytes circulating in the blood. However, non-erythroid hemoglobins have been previously reported in other cell Globins are hemo-containing proteins, have the ability to types including human and rodent neurons of embryonic bind gaseous ligands [oxygen (O2), nitric oxide (NO) and and adult brain, but not astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. carbon monoxide (CO)] reversibly. They have been described Human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most aggres- in prokaryotes, fungi, plants and animals with an enormous sive tumor among gliomas. However, despite extensive basic diversity of structure and function (1). To date, hemoglobin, and clinical research studies on GBM cells, little is known myoglobin, neuroglobin (Ngb) and cytoglobin (Cygb) repre- about glial defence mechanisms that allow these cells to sent the vertebrate globin family with distinct function and survive and resist various types of treatment. We have tissue distributions (2). During ontogeny, developing erythro- shown previously that the newest members of vertebrate blasts sequentially express embryonic {[Gower 1 (ζ2ε2), globin family, neuroglobin (Ngb) and cytoglobin (Cygb), are Gower 2 (α2ε2), and Portland 1 (ζ2γ2)] to fetal [Hb F(α2γ2)] expressed in human GBM cells. -

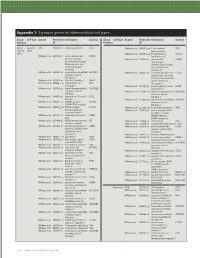

Technical Note, Appendix: an Analysis of Blood Processing Methods to Prepare Samples for Genechip® Expression Profiling (Pdf, 1

Appendix 1: Signature genes for different blood cell types. Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Fraction ID Fraction ID Mono- Lympho- GSK 203547_at CD4 antigen (p55) CD4 Whitney et al. 209813_x_at T cell receptor TRG nuclear cytes gamma locus cells Whitney et al. 209995_s_at T-cell leukemia/ TCL1A Whitney et al. 203104_at colony stimulating CSF1R lymphoma 1A factor 1 receptor, Whitney et al. 210164_at granzyme B GZMB formerly McDonough (granzyme 2, feline sarcoma viral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte- (v-fms) oncogene associated serine homolog esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203290_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQA1 Whitney et al. 210321_at similar to granzyme B CTLA1 complex, class II, (granzyme 2, cytotoxic DQ alpha 1 T-lymphocyte-associated Whitney et al. 203413_at NEL-like 2 (chicken) NELL2 serine esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203828_s_at natural killer cell NK4 (H. sapiens) transcript 4 Whitney et al. 212827_at immunoglobulin heavy IGHM Whitney et al. 203932_at major histocompatibility HLA-DMB constant mu complex, class II, Whitney et al. 212998_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB1 DM beta complex, class II, Whitney et al. 204655_at chemokine (C-C motif) CCL5 DQ beta 1 ligand 5 Whitney et al. 212999_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB Whitney et al. 204661_at CDW52 antigen CDW52 complex, class II, (CAMPATH-1 antigen) DQ beta 1 Whitney et al. 205049_s_at CD79A antigen CD79A Whitney et al. 213193_x_at T cell receptor beta locus TRB (immunoglobulin- Whitney et al. 213425_at Homo sapiens cDNA associated alpha) FLJ11441 fis, clone Whitney et al. 205291_at interleukin 2 receptor, IL2RB HEMBA1001323, beta mRNA sequence Whitney et al. -

Molecular Epidemiology and Hematologic Characterization of Δβ

Jiang et al. BMC Medical Genetics (2020) 21:43 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-0981-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Molecular epidemiology and hematologic characterization of δβ-thalassemia and hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin in 125,661 families of greater Guangzhou area, the metropolis of southern China Fan Jiang1,2, Liandong Zuo2, Dongzhi Li2, Jian Li2, Xuewei Tang2, Guilan Chen2, Jianying Zhou2, Hang Lu2 and Can Liao1,2* Abstract Background: Individuals with δβ-thalassemia/HPFH and β-thalassemia usually present with intermedia or thalassemia major. No large-scale survey on HPFH/δβ-thalassemia in southern China has been reported to date. The purpose of this study was to examine the molecular epidemiology and hematologic characteristics of these disorders in Guangzhou, the largest city in Southern China, to offer advice for thalassemia screening programs and genetic counseling. Methods: A total of 125,661 couples participated in pregestational thalassemia screening. 654 subjects with fetal hemoglobin (HbF) level ≥ 5% were selected for further investigation. Gap-PCR combined with Multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification (MLPA) was used to screen for β-globin gene cluster deletions. Gene sequencing for the promoter region of HBG1 /HBG2 gene was performed for all those subjects. Results: A total of 654 individuals had hemoglobin (HbF) levels≥5, and 0.12% of the couples were found to be heterozygous for HPFH/δβ-thalassemia, including Chinese Gγ (Aγδβ)0-thal, Southeast Asia HPFH (SEA-HPFH), Taiwanese deletion and Hb Lepore–Boston–Washington. The highest prevalence was observed in the Huadu district and the lowest in the Nansha district. Three cases were identified as carrying β-globin gene cluster deletions, which had not been previously reported. -

Table S1. Identified Proteins with Exclusive Expression in Cerebellum of Rats of Control, 10Mg F/L and 50Mg F/L Groups

Table S1. Identified proteins with exclusive expression in cerebellum of rats of control, 10mg F/L and 50mg F/L groups. Accession PLGS Protein Name Group IDa Score Q3TXS7 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 435 Control Q9CQX8 28S ribosomal protein S36_ mitochondrial 197 Control P52760 2-iminobutanoate/2-iminopropanoate deaminase 315 Control Q60597 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase_ mitochondrial 67 Control P24815 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Delta 5-->4-isomerase type 1 84 Control Q99L13 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase_ mitochondrial 114 Control P61922 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase_ mitochondrial 470 Control P10852 4F2 cell-surface antigen heavy chain 220 Control Q8K010 5-oxoprolinase 197 Control P47955 60S acidic ribosomal protein P1 190 Control P70266 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2_6-bisphosphatase 1 113 Control Q8QZT1 Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase_ mitochondrial 402 Control Q9R0Y5 Adenylate kinase isoenzyme 1 623 Control Q80TS3 Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 59 Control B7ZCC9 Adhesion G-protein coupled receptor G4 139 Control Q6P5E6 ADP-ribosylation factor-binding protein GGA2 45 Control E9Q394 A-kinase anchor protein 13 60 Control Q80Y20 Alkylated DNA repair protein alkB homolog 8 111 Control P07758 Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-1 78 Control P22599 Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-2 78 Control Q00896 Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-3 78 Control Q00897 Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-4 78 Control P57780 Alpha-actinin-4 58 Control Q9QYC0 Alpha-adducin 270 Control Q9DB05 Alpha-soluble NSF attachment protein 156 Control Q6PAM1 Alpha-taxilin 161 -

Identification of Novel HPFH-Like Mutations by CRISPR Base Editing That Elevates the Expression of Fetal Hemoglobin

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.178715; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Identification of novel HPFH-like mutations by CRISPR base editing that elevates the expression of fetal hemoglobin Nithin Sam Ravi1,3, Beeke Wienert4,8,9, Stacia K. Wyman4, Jonathan Vu4, Aswin Anand Pai2, Poonkuzhali Balasubramanian2, Yukio Nakamura7, Ryo Kurita10, Srujan Marepally1, Saravanabhavan Thangavel1, Shaji R. Velayudhan1,2, Alok Srivastava1,2, Mark A. DeWitt 4,5, Jacob E. Corn4,6, Kumarasamypet M. Mohankumar1* 1. Centre for Stem Cell Research (a unit of inStem, Bengaluru), Christian Medical College Campus, Bagayam, Vellore-632002, Tamil Nadu, India. 2. Department of Haematology, Christian Medical College Hospital, IDA Scudder Rd, Vellore-632002, Tamil Nadu, India. 3. Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 011, Kerala, India. 4. Innovative Genomics Institute, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California- 94704, USA. 5. Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics, University of California - Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California - 90095, USA. 6. Institute of Molecular Health Sciences, Department of Biology, ETH Zurich, Otto-Stern- Weg, Zurich - 8092, Switzerland. 7. Cell Engineering Division, RIKEN BioResource Center, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0074, Japan. 8. Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology, Gladstone Institutes, San Francisco, California -94158, USA 9. School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, University of New South Wales - 2052, Sydney, Australia. 10. Research and Development Department Central Blood Institute Blood Service Headquarters Japanese Red Cross Society, 2-1-67 Tatsumi, Tokyo, 135-8521, Japan *Corresponding Author: Dr. -

Normal, C=Critical

Patient Report |FINAL Client: Example Client ABC123 Patient: Patient, Example 123 Test Drive Salt Lake City, UT 84108 DOB 7/22/1970 UNITED STATES Gender: Female Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Physician: Doctor, Example Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Collection Date: 00/00/0000 00:00 Hemoglobin Evaluation Reflexive Cascade ARUP test code 2005792 Hemoglobin A 97.1 % (Ref Interval: 95.0-97.9) Hemoglobin A2 2.6 % (Ref Interval: 2.0-3.5) Hemoglobin F 0.3 % (Ref Interval: 0.0-2.1) REFERENCE INTERVAL: Hemoglobin F Access complete set of age- and/or gender-specific reference intervals for this test in the ARUP Laboratory Test Directory (aruplab.com). Hemoglobin S 0.0 % (Ref Interval: 0.0-0.0) Hemoglobin C 0.0 % (Ref Interval: 0.0-0.0) Hemoglobin E 0.0 % (Ref Interval: 0.0-0.0) Hemoglobin - Other 0.0 % (Ref Interval: 0.0-0.0) Sickle Cell Solubility Not Performed Hemoglobin, Capillary Electrophoresis Performed Hemoglobin Evaluation See Note Beta Globin Full Gene Sequencing Not Applicable H=High, L=Low, *=Abnormal, C=Critical Patient: Patient, Example ARUP Accession: 21-048-400496 Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Page 1 of 4 | Printed: 3/11/2021 11:41:09 AM 4848 Patient Report |FINAL Beta Globin (HBB) Del/Dup Result Not Applicable Alpha Thalassemia HBA1 and HBA2 Seq Not Applicable Gamma Globin (HBG1 and HBG2) Sequencing Not Applicable Hemoglobin Cascade Interpretation See Note H=High, L=Low, *=Abnormal, C=Critical Patient: Patient, Example ARUP Accession: 21-048-400496 Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Page 2 of 4 | Printed: 3/11/2021 11:41:09 AM 4848 Patient Report |FINAL RESULT Normal hemoglobin evaluation. -

Apoptotic Cells Inflammasome Activity During the Uptake of Macrophage

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 29, 2021 is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 26 of which you can access for free at: 2012; 188:5682-5693; Prepublished online 20 from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication April 2012; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103760 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/188/11/5682 Complement Protein C1q Directs Macrophage Polarization and Limits Inflammasome Activity during the Uptake of Apoptotic Cells Marie E. Benoit, Elizabeth V. Clarke, Pedro Morgado, Deborah A. Fraser and Andrea J. Tenner J Immunol cites 56 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2012/04/20/jimmunol.110376 0.DC1 This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/188/11/5682.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2012 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 29, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Complement Protein C1q Directs Macrophage Polarization and Limits Inflammasome Activity during the Uptake of Apoptotic Cells Marie E. -

Genome Editing of HBG1/2 Promoter Leads to Robust Hbf Induction in Vivo While Editing of BCL11A Erythroid Enhancer Shows Erythroid Defect

Genome Editing of HBG1/2 Promoter Leads to Robust HbF Induction In Vivo While Editing of BCL11A Erythroid Enhancer Shows Erythroid Defect Kai-Hsin Chang, Minerva Sanchez, Jack Heath, Edouard de Dreuzy, Scott Haskett, Abigail Vogelaar, Kiran Gogi, Jen DaSilva, Tongyao Wang, Andrew Sadowski, Gregory Gotta, Jamaica Siwak, Ramya Viswanathan, Katherine Loveluck, Hoson Chao, Eric Tillotson, Aditi Chalishazar, Abhishek Dass, Frederick Ta, Emily Brennan, Diana Tabbaa, Eugenio Marco, John Zuris, Deepak Reyon, Meltem Isik, Ari Friedland, Terence Ta, Fred Harbinski, Georgia Giannoukos, Sandra Teixeira, Christopher Wilson, Charlie Albright, Haiyan Jiang Editas Medicine, Inc., Cambridge, MA 60th Annual Meeting and Exposition of American Society of Hematology December 2, 2018, San Diego, CA © 2018 Editas Medicine Overview Etiology of Sickle Cell Disease In Vivo Study Design to Evaluate Two Approaches to Increase Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF) Expression Effect of Downregulating BCL11A Expression by Targeting its Erythroid Enhancer Editing Cis-regulatory Elements in b-Globin Locus Conclusion © 2018 Editas Medicine Etiology of Sickle Cell Disease Amino Hemoglobin Low DNA Acid Tetramer O2 a a a a b-globin GLU G A G b b b b HbA a a a a a a a a s s s VAL b b b -globin G T G bs bs bs bs bs bs HbS HbS Fiber • Sickle cell disease (SCD) is caused by a single mutation E6V of the b-globin chain, leading to polymerization of hemoglobin (Hb) and formation of sickle hemoglobin (HbS) fibers when deoxygenated. • Symptoms include anemia, acute chest syndrome, pain crises, and an array of other complications. • Patients suffer significant morbidity and early mortality. -

Molecular Profiling of Innate Immune Response Mechanisms in Ventilator-Associated 2 Pneumonia

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.08.899294; this version posted January 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Title: Molecular profiling of innate immune response mechanisms in ventilator-associated 2 pneumonia 3 Authors: Khyatiben V. Pathak1*, Marissa I. McGilvrey1*, Charles K. Hu3, Krystine Garcia- 4 Mansfield1, Karen Lewandoski2, Zahra Eftekhari4, Yate-Ching Yuan5, Frederic Zenhausern2,3,6, 5 Emmanuel Menashi3, Patrick Pirrotte1 6 *These authors contributed equally to this work 7 Affiliations: 8 1. Collaborative Center for Translational Mass Spectrometry, Translational Genomics Research 9 Institute, Phoenix, Arizona 85004 10 2. Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, Arizona 85004 11 3. HonorHealth Clinical Research Institute, Scottsdale, Arizona 85258 12 4. Applied AI and Data Science, City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, California 91010 13 5. Center for Informatics, City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, California 91010 14 6. Center for Applied NanoBioscience and Medicine, University of Arizona, Phoenix, Arizona 15 85004 16 Corresponding author: 17 Dr. Patrick Pirrotte 18 Collaborative Center for Translational Mass Spectrometry 19 Translational Genomics Research Institute 20 445 North 5th Street, Phoenix, AZ, 85004 21 Tel: 602-343-8454; 22 [[email protected]] 23 Running Title: Innate immune response in ventilator-associated pneumonia 24 Key words: ventilator-associated pneumonia; endotracheal aspirate; proteome, metabolome; 25 neutrophil degranulation 26 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.08.899294; this version posted January 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Impact of Rare and Common Genetic Variants on Diabetes Diagnosis by Hemoglobin A1c in Multi-Ancestry Cohorts

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/643932; this version posted May 28, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Impact of rare and common genetic variants on diabetes 2 diagnosis by hemoglobin A1c in multi-ancestry cohorts: 3 The Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine Program 4 5 Authors 6 Chloé Sarnowski,1,35,37,* Aaron Leong,2,3,4,35,38,** Laura M Raffield,5 Peitao Wu,1 Paul S de 7 Vries,6 Daniel DiCorpo,1 Xiuqing Guo,7 Huichun Xu,8 Yongmei Liu,9 Xiuwen Zheng,10 Yao 8 Hu,11 Jennifer A Brody,12 Mark O Goodarzi,13 Bertha A Hidalgo,14 Heather M Highland,15 9 Deepti Jain,10 Ching-Ti Liu,1 Rakhi P Naik,16 James A Perry,17 Bianca C Porneala,2 Elizabeth 10 Selvin,18 Jennifer Wessel,19,20 Bruce M Psaty,12,21,22 Joanne E Curran,23 Juan M Peralta,23 John 11 Blangero,23 Charles Kooperberg,11 Rasika Mathias,18,24 Andrew D Johnson,25,26 Alexander P 12 Reiner,11,27 Braxton D Mitchell,8,28 L Adrienne Cupples,1,25 Ramachandran S Vasan,25,29,30 13 Adolfo Correa,31,32 Alanna C Morrison,6 Eric Boerwinkle,6,33 Jerome I Rotter,7 Stephen S Rich,34 14 Alisa K Manning,2,3,4 Josée Dupuis,1,25,36 James B Meigs,2,3,4,36 on behalf of the Trans-Omics for 15 Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Diabetes and TOPMed Hematology and Hemostasis working 16 groups and the NHLBI TOPMed Consortium.