Sample Laws5006: Torts + Contracts Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Economic Torts Jay Feinman Rutgers University-Camden

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Kentucky Kentucky Law Journal Volume 95 | Issue 4 Article 4 2007 Teaching Economic Torts Jay Feinman Rutgers University-Camden Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Torts Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Feinman, Jay (2007) "Teaching Economic Torts," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 95 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol95/iss4/4 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Teaching Economic Torts Jay M. Feinman1 The primary goal of this Article is to proselytize for the teaching of an eco- nomic torts course in the upper-level law school curriculum, particularly a course that focuses on the business torts that form the core of a typical non-personal injury civil litigation practice. In service of that goal, the Ar- ticle surveys traditional and contemporary efforts to define the scope of economic torts and to provide teaching materials, identifies some themes and issues in those efforts, and comments on teaching methods that are particularly appropriate for the course. Tort law is, of course, a staple of the first-year law school curriculum, and most tort courses spend the bulk of their time on issues arising out of physical injuries to persons and, to a lesser extent, property. -

Torts a Modern Approach

Torts LongBaxter_Torts_5pp.indb 1 1/30/20 10:51 AM LongBaxter_Torts_5pp.indb 2 1/30/20 10:51 AM Torts A Modern Approach Alex B. Long Williford Gragg Distinguished Professor of Law University of Tennessee College of Law Teri Dobbins Baxter Williford Gragg Distinguished Professor of Law University of Tennessee College of Law Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina LongBaxter_Torts_5pp.indb 3 1/30/20 10:51 AM Copyright © 2020 Alex B. Long and Teri Dobbins Baxter All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-5310-1723-1 e-ISBN 978-1-5310-1724-8 LCCN 2019953043 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America LongBaxter_Torts_5pp.indb 4 1/30/20 10:51 AM Contents Table of Cases xxi Authors’ Note xxv Chapter 1 • Introduction 3 A. History 4 B. Fault as the Standard Basis for Liability 5 Van Camp v. McAfoos 5 Notes 6 C. Policies Under lying Tort Law 7 Rhodes v. MacHugh 8 Notes 9 Part 1 • Intentional Torts 11 Chapter 2 • Intentional Harms to Persons 13 A. Battery 15 1. Act with Intent 15 Garratt v. Dailey 15 Polmatier v. Russ 17 Notes 20 2. Intent to Cause Harmful or Offensive Contact 21 White v. Muniz 21 Notes 23 3. Such Contact Results 23 a. Causation 23 b. Contact 23 Reynolds v. MacFarlane 23 Notes 26 c. Harmful or Offensive Contact 26 Balas v. Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. 26 Fuerschbach v. Southwest Airlines Co. 27 Notes 28 v LongBaxter_Torts_5pp.indb 5 1/30/20 10:51 AM vi CONTEnts B. -

New Rules for Promissory Fraud

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2006 New Rules for Promissory Fraud Gregory Klass Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Ian Ayres Yale Law School Georgetown Business, Economics and Regulatory Law Research Paper No. 936869 Copyright 2006 by the Arizona Board of Regents, Gregory Klass, and Ian Ayres. Reprinted with permission of the authors and publisher. This article originally appeared in Arizona Law Review, Vol. 48, No. 4, P. 957. This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/125 http://ssrn.com/abstract=936869 48 Ariz. L. Rev. 957-971 (2006) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Contracts Commons NEW RULES FOR PROMISSORY FRAUD Ian Ayres & Gregory Klass* Experience is complex. The job of theory is to simplify and unify, to abstract from the blooming, buzzing confusion and find some basic rules we can use to guide us through it. Contract theory is a prime example. Theorists treat legally binding promises as elemental speech acts, utterances that accomplish one thing: put the promisor under an obligation to perform. This simplification has allowed contract theory to focus on the deep questions that follow: When do speech acts create such an obligation? How should we interpret the scope of the duty undertaken? What should be the legal consequences of its violation? These basic questions, along with a few others, have given rise to volumes of thought on how legal liability should be structured. -

Tort, Speech, and the Dubious Alchemy of State Action

TORT, SPEECH, AND THE DUBIOUS ALCHEMY OF STATE ACTION Cristina Carmody Tilley∗ ABSTRACT Plaintiffs have historically used defamation, privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress to vindicate their dignitary interests. But fifty years ago in New York Times v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court reimagined these private law torts as public law causes of action that explicitly privileged speech over dignity. This Article claims that Sullivan was a misguided attempt at alchemy, manipulating state action doctrine to create more of a precious commodity—speech— while preserving a tort channel for the most deserving plaintiffs. In Sullivan the Court departed from its usual practice of narrowly defining the relevant state action in constitutional challenges to private law matters. Instead, it defined state action to include not just the isolated verdict being appealed but the entirety of the private law that produced the questionable verdict. This approach aggrandized the Court’s authority to “fix” private law in the dignitary tort arena, where it seemed to fear that insular communities could chill important news coverage by imposing parochial norms onto the national community. The Court used its enhanced remedial authority to design a national constitutional common law of dignitary tort. In the quasi-statutory scheme that emerged, the Court attempted to strike an ex ante balance between valuable speech and wrongful behavior by conditioning liability on different scienter requirements for different categories of plaintiff. But the Sullivan project is rapidly failing. Operationally, insignificant but injurious speech such as revenge porn has flourished under the Court’s brittle categorization matrix. Conceptually, the private law message that speakers owe some duty to those they discuss has been supplanted with a public law message that they have no duty of care. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521820804 - Privacy, Property and Personality: Civil Law Perspectives on Commercial Appropriation Huw Beverley-Smith, Ansgar Ohly and Agnes Lucas-Schloetter Excerpt More information 1 Introduction The commercial value of aspects of personality Fame has an attractive force that lends itself well to commercial exploita- tion. Attributes of an individual’s personality, such as a person’s name, voice or likeness, are often used in advertising or merchandising in order to increase the attractiveness and saleability of goods and services. The practice is not new and dates from at least the nineteenth century.1 Since the advent of the industrial revolution and the increased proliferation of consumer products, advertisers and merchandisers sought new ways to draw the consuming public’s attention and to differentiate their products and services from those of their rivals. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the names and images of well-known persons such as the French actress Sarah Bernhardt,2 German Count Zeppelin3 and the American inventor Thomas A. Edison4 were used to advertise, respec- tively, perfumes, cigars and medicinal products. Moreover, people with no obvious public profile began to find indicia of their identity used in advertising, resulting in varying degrees of distress, annoyance or indignation. This reflects the fact that manufacturers of goods and suppliers of services can find the use of the images of a vast range of people beneficial to them in some way. Apart from the more common modern examples such as pop-stars and sportsmen, people of high professional standing, holders of public office, and politicians are often desirable people with whom to associate products or services. -

Definition Overview Remedies

30/09/2020 Tort | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute Tort Definition A tort is an act or omission that gives rise to injury or harm to another and amounts to a civil wrong for which courts impose liability. In the context of torts, "injury" describes the invasion of any legal right, whereas "harm" describes a loss or detriment in fact that an individual suffers.1 Overview The primary aims of tort law are to provide relief to injured parties for harms caused by others, to impose liability on parties responsible for the harm, and to deter others from committing harmful acts. Torts can shift the burden of loss from the injured party to the party who is at fault or better suited to bear the burden of the loss. Typically, a party seeking redress through tort law will ask for damages in the form of monetary compensation. Less common remedies include injunction and restitution. The boundaries of tort law are defined by common law and state statutory law. Judges, in interpreting the language of statutes, have wide latitude in determining which actions qualify as legally cognizable wrongs, which defenses may override any given claim, and the appropriate measure of damages. Although tort law varies by state, many courts utilize the Restatement of Torts (2nd) as an influential guide. Torts fall into three general categories: intentional torts (e.g., intentionally hitting a person); negligent torts (e.g., causing an accident by failing to obey traffic rules); and strict liability torts (e.g., liability for making and selling defective products - see Products Liability). -

Corrective Justice and the Unlawful Means Tort: Is There a Right to Trade?

Dalhousie Journal of Legal Studies Volume 28 Article 34 1-1-2019 Corrective Justice and the Unlawful Means Tort: Is There A Right to Trade? Kerry Sun Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/djls Part of the Law and Economics Commons, and the Torts Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kerry Sun, "Corrective Justice and the Unlawful Means Tort: Is There A Right to Trade?" (2019) 28 Dal J Leg Stud 1. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dalhousie Journal of Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 28 Dalhousie Journal of Legal Studies 167 CORRECTIVE JUSTICE AND THE UNLAWFUL MEANS TORT: IS THERE A RIGHT TO TRADE? Kerry Sun* ABSTRACT This paper investigates the extent to which the theory of corrective justice can account for the purpose, structure, and elements of the tort of unlawful interference with economic relations. It considers various proposed accounts of the tort, contending that the tort cannot be justified as an exception to the privity doctrine, a response to the defendant’s attempts to assert indirect control over the plaintiff, or a form of liability stretching. Extending a proposed account of the tort based on the theory of abuse of rights, this paper develops the idea of a “right to trade” that is founded on the conception of rights, remedies, and the systematicity of the legal order underlying corrective justice. -

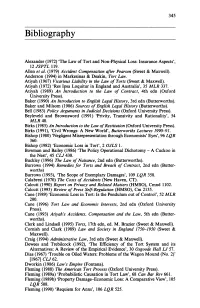

Bibliography

345 Bibliography Alexander (1972) 'The Law of Tort and Non-Physical Loss: Insurance Aspects', 12 JSPTL 119. Allen et al. (1979) Accident Compensation after Pearson (Sweet & Maxwell). Anderson (1994) in Markesinas & Deakin, Tort Law. Atiyah (1967) Vicarious Liability in the Law of Torts (Sweet & Maxwell). Atiyah (1972) 'Res Ipsa Loquitur in England and Australia', 35 MLR 337. Atiyah (1989) An Introduction to the Law of Contract, 4th edn (Oxford University Press). Baker (1990) An Introduction to English Legal History, 3rd edn (Butterworths). Baker and Milsom (1986) Sources of English Legal History (Butterworths). Bell (1983) Policy Arguments in Judicial Decisions (Oxford University Press). Beyleveld and Brownsword (1991) 'Privity, Transivity and Rationality', 54 MLR48. Birks (1985) An Introduction to the Law of Restitution (Oxford University Press). Birks (1991), 'Civil Wrongs: A New World', Butterworths Lectures 1990-91. Bishop (1980) 'Negligent Misrepresentation through Economists' Eyes', 96 LQR 360. Bishop (1982) 'Economic Loss in Tort', 2 OJLS 1. Bowman and Bailey (1986) 'The Policy Operational Dichotomy - A Cuckoo in the Nest', 45 CLJ 430. Buckley (1996) The Law of Nuisance, 2nd edn (Butterworths). Burrows (1994) Remedies for Torts and Breach of Contract, 2nd edn (Butter- worths) Burrows (1993), 'The Scope of Exemplary Damages', 109 LQR 358. Calabresi (1970) The Costs of Accidents (New Haven, CT). Calcutt (1990) Report on Privacy and Related Matters (HMSO), Cmnd 1102. Calcutt (1993) Review of Press Self-Regulation (HMSO), Cm 2135. Cane (1989) 'Economic Loss in Tort: Is the Pendulum out of Control', 52 MLR 200. Cane (1996) Tort Law and Economic Interests, 2nd edn (Oxford University Press). Cane (1993) Atiyah's Accidents, Compensation and the Law, 5th edn (Butter worths). -

Reference Guide on Estimation of Economic Damages, 425 Mark A

Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence Third Edition Committee on the Development of the Third Edition of the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence Committee on Science, Technology, and Law Policy and Global Affairs FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 The Federal Judicial Center contributed to this publication in furtherance of the Center’s statutory mission to develop and conduct educational programs for judicial branch employ- ees. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Judicial Center. NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. The development of the third edition of the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence was sup- ported by Contract No. B5727.R02 between the National Academy of Sciences and the Carnegie Corporation of New York and a grant from the Starr Foundation. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Academies or the organizations that provided support for the project. International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-21421-6 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-21421-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reference manual on scientific evidence. — 3rd ed. -

The Modern Law of Torts

The Modern Law of Torts Donoho_6pp.indb 1 6/9/20 8:41 AM Donoho_6pp.indb 2 6/9/20 8:41 AM The Modern Law of Torts A Contemporary Approach Douglas Lee Donoho Professor of Law Nova Southeastern University Shepard Broad College of Law Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina Donoho_6pp.indb 3 6/9/20 8:41 AM Copyright © 2020 Douglas Lee Donoho All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-5310-1294-6 e-ISBN 978-1-5310-1295-3 LCCN 2020933840 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, NC 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www . caplaw . com Printed in the United States of Amer i ca Donoho_6pp.indb 4 6/9/20 8:41 AM To Melissa and our amazing progeny, Madison, Quinn and Ailish. You make me happy and keep me in the real world. You are, in fact, the best. Thank you. Donoho_6pp.indb 5 6/9/20 8:41 AM Donoho_6pp.indb 6 6/9/20 8:41 AM Contents Table of Cases xxix About This Book and How to Use It xxxiii Chapter 1 • Introduction to Tort Law 3 A. General Background: What Is a Tort? 3 B. Elements, Causes of Action and Legal Method 6 Assignment 1.1 8 C. Introduction to Practice and Procedure 8 D. Context: The Policy Backdrop 10 PART ONE • INTENTIONAL TORTS Chapter 2 • The Intent Element 19 I. Black Letter Foundations 19 A. Introduction and Overview 19 B. Basic Definition of Intent 20 Assignment 2.1 23 C. Simple Applications of the Intent Definition 23 D. -

Q&A Series Torts Law, Fifth Edition

Q&A Series Torts Law FIFTH EDITION Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney • Portland, Oregon Q&A Series Torts Law FIFTH EDITION Dr David Green Barrister Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney • Portland, Oregon Fifth edition first published in Great Britain 2003 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: + 44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com Published in the United States by Cavendish Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services, 5804 NE Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213–3644, USA Published in Australia by Cavendish Publishing (Australia) Pty Ltd 3/303 Barrenjoey Road, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia © Green, D 2003 First edition 1993 Second edition 1995 Third edition 1998 Fourth edition 2001 Fifth edition 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Cavendish Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Cavendish Publishing Limited, at the address above. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Green, David, 1935– Tort – 5th ed – (Q&A series) 1 Torts—England—Miscellanea 2 Torts—Wales—Miscellanea I Title 346.4'2'03 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available ISBN 1-85941-629-2 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Printed and bound in Great Britain PREFACE The many changes that have occurred in the law of tort since the earlier editions of this work were published have necessitated a thorough revision throughout the book. -

MLL217 – Misleading Conduct and Economic Torts Notes

MLL217 – Misleading Conduct and Economic Torts Notes MLL217 – Misleading Conduct and Economic Torts Notes ........................................................................ i Defamation ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Libel and Slander (s 7 Defamation Act) ............................................................................................. 1 Restrictions on Bringing Action ........................................................................................................ 1 Deceased Persons (s 10 Defamation Act) ..................................................................................... 1 Corporations (s 9 Defamation Act) ............................................................................................... 1 Public Bodies ............................................................................................................................... 2 Establishing Defamation .................................................................................................................. 2 Elements of Defamation .............................................................................................................. 2 Subject matter conveys a defamatory meaning or imputation .................................................. 2 Establish if the imputations are in fact defamatory ................................................................... 4 Defamatory matter was published ..........................................................................................