Foma Q-Score 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Svwsge Bundesliga Matchday 34 / Sv Werder Bremen – Eintracht Frankfurt / Global Tv Channels and Timings

BUNDESLIGA MATCHDAY 34 / SV WERDER BREMEN – EINTRACHT FRANKFURT / GLOBAL TV CHANNELS AND TIMINGS COUNTRY CHANNEL LOCAL TIME PROGRAMME Albania Eurosport 2 15:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Albania SuperSport 2 HD 15:30 Werder-Frankfurt Austria Sky Bundesliga 3 15:15 Live Fußball: Bundesliga 34. Spieltag Belgium Play Sports HD2 15:25 Werder Bremen - Frankfurt (14 mei) Belgium Fox Sports 2 15:25 SV Werder Bremen-Eintracht Frankfurt Bosnia and Herzegovina Eurosport 2 15:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Brunei Fox Sports 3 21:00 Bundesliga 2015/16 Bulgaria Eurosport 2 16:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Cambodia Fox Sports 3 20:00 Bundesliga 2015/16 Canada Sportsnet World 09:30 Bundesliga: SV Werder Bremen v Eintracht Frankfurt Croatia Eurosport 2 15:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Cyprus Sports+ 3 16:30 SV WERDER BREMEN - EINTRACHT FRANKFURT Czech Republic Eurosport 2 15:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Denmark Eurosport 2 15:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Estonia Eurosport 2 16:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Faroe Islands Eurosport 2 14:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Finland Eurosport 2 16:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Hong Kong Fox Sports 3 21:00 Bundesliga 2015/16 Hungary Eurosport 2 15:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. round: Werder Bremen (Germany) - Frankfurt (Germany) (135min) Iceland Eurosport 2 13:15 FOOTBALL: Bundesliga - 34. -

21T1BL – Topps Tier One Bundesliga– Checklist Autograph Cards: TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS TO-SB Sebastiaan Bornauw 1. FC Köln TO

21T1BL – Topps Tier One Bundesliga– Checklist Autograph cards: TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS TO-SB Sebastiaan Bornauw 1. FC Köln TO-MT Marcus Thuram Borussia Mönchengladbach TO-JK Joshua Kimmich FC Bayern München TO-SS Suat Serdar FC Schalke 04 TO-KP Krzysztof Piątek Hertha Berlin TO-CN Christopher Nkunku RB Leipzig TO-MH Martin Hinteregger Eintracht Frankfurt BREAK OUT AUTOGRAPHS BO-IJ Ismail Jakobs 1. FC Köln BO-NK Noah Katterbach 1. FC Köln BO-JS Jeremiah St. Juste 1. FSV Mainz 05 BO-P Paulinho Bayer 04 Leverkusen BO-FW Florian Wirtz Bayer 04 Leverkusen BO-ET Edmond Tapsoba Bayer 04 Leverkusen BO-GR Giovanni Reyna Borussia Dortmund BO-EN Evan N'Dicka Eintracht Frankfurt BO-DS Djibril Sow Eintracht Frankfurt BO-FU Felix Uduokhai FC Augsburg BO-RO Reece Oxford FC Augsburg BO-AD Alphonso Davies FC Bayern München BO-PS Pascal Stenzel VfB Stuttgart BO-OM Orel Mangala VfB Stuttgart BO-MK Marc Oliver Kempf VfB Stuttgart BO-MG Mattéo Guendouzi Hertha Berlin BO-JT Jordan Torunarigha Hertha Berlin BO-NST Niklas Stark Hertha Berlin BO-JK Justin Kluivert RB Leipzig BO-DU Dayot Upamecano RB Leipzig BO-KL Konrad Laimer RB Leipzig BO-KS Keven Schlotterbeck Sport-Club Freiburg BO-CK Chang-hoon Kwon Sport-Club Freiburg BO-NS Nils Seufert DSC Arminia Bielefeld BO-SO Stefan Ortega Moreno DSC Arminia Bielefeld BO-MF Marco Friedl SV Werder Bremen BO-ME Maximilian Eggestein SV Werder Bremen BO-DG Dennis Geiger TSG Hoffenheim BO-DSA Diadie Samassékou TSG Hoffenheim BO-RK Robin Knoche 1. FC Union Berlin BO-NSC Nico Schlotterbeck 1. -

The Vfl Wolfsburg Sustainability Report 2016

GEMEINSAM BEWEGEN THE VFL WOLFSBURG SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2016 WWW.VFL-WOLFSBURG.DE MOVING TOGEHTER 4 | CONCENTRATING ON WHAT IS CRUCIAL ABOUT THIS REPORT VfL Wolfsburg is traditionally very closely connected with soci- ment and the Lord Mayor of Wolfsburg are then followed by a ety, and in the same way as classic industrial companies, is also portrait of VfL Wolfsburg. The subsequent chapters in the re- responsible with respect to society (Corporate Social Respon- port focus on the club’s main CSR spheres of action: “Strategy sibility, CSR). The club is very aware of its responsibility for the and Management”, “Employees”, “Environment” and “Society”, consequences of its actions on people and the environment, as well as “Fans and Members”. and has therefore strongly anchored its commitment to CSR in its corporate philosophy. It wants to be seen as a responsible Within each chapter, the report presents how VfL strategi- player nationally and internationally, and to therefore occupy a cally tackles the main topics, the measures it implements to leading position in professional football. The central commu- achieve its targets, and the metrics it uses to control progress. nication instrument for this purpose is its sustainability or CSR VfL Wolfsburg collects those metrics which help improve its report. This is addressed in particular at fans, employees, part- measures in the football business. These are therefore differ- ners and VfL sponsors, as well as Volkswagen AG. Moreover, it ent in some cases to the metrics presented by classic business- is also aimed at non-governmental organisations and associa- es. Each chapter also includes an overview of the special mile- tions representing specific interests, as well as representatives stones achieved during the reporting period; and an outlook of politics, science and research. -

Bundesliga-Terminplan Des Fc Bayern München

General Terms and Conditions of FC Bayern München AG (FCB) and DO & CO München GmbH (DO & CO) concerning the purchase of entrance tickets for the FC Bayern Erlebniswelt/Arena Tours via internet and via the Service Team 1 Scope of these terms and conditions The following terms and conditions, provided here for reference with your confirmation email, apply exclusively to orders for FC Bayern Erlebniswelt or Arena Tours tickets (individual tickets and group bookings) placed via the internet (www.fcbayern.com/erlebniswelt, www.allianz-arena.com/erlebniswelt) and/or via the Service Team. 2 Conclusion and contents of contracts 2.1 FC Bayern Erlebniswelt An overview of ticketing options and prices for the FC Bayern Erlebniswelt (individual tickets and group bookings) is available at www.fcbayern.com/erlebniswelt. The contractual partner for ticket orders for the Erlebniswelt, including those sold as 'Combitickets', is FC Bayern München AG (FCB). Orders are placed via telephone, by completing the online booking form, or by completing and sending off the application form. The ticket will be supplied either as a Print@Home document or will be deposited at the ticket desk in the foyer of the FC Bayern Erlebniswelt upon request. Entrance tickets cannot be returned or refunded. Lost or damaged tickets cannot be replaced. 2.2 Birthdays at the FC Bayern Erlebniswelt The offers and prices for birthdays are listed at www.fcbayern.com/erlebniswelt and www.allianz-arena.com, and at the FCB KidsClub website (www.fcbayern.com/kidsclub) for FCB KidsClub children's birthday parties in the Erlebniswelt. The contractual partner for birthday ticket orders for the Erlebniswelt is FC Bayern München AG (FCB). -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2018/19 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Sarpsborg Stadium - Sarpsborg Thursday 29 November 2018 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Sarpsborg 08 FF Group I - Matchday 5 Beşiktaş JK Last updated 28/11/2018 04:44CET Match background 2 Legend 4 1 Sarpsborg 08 FF - Beşiktaş JK Thursday 29 November 2018 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Sarpsborg Stadium, Sarpsborg Match background European colts Sarpsborg are in the thick of the race for qualification from Group I and will eliminate continental thoroughbreds Beşiktaş with victory in Norway on matchday five. • Newcomers to Europe this season, Sarpsborg have already played 12 games in this UEFA Europa League campaign. Having gained their first group stage win at home to Genk on matchday two (3-1), they drew both Scandinavian derbies with Malmö 1-1 and are level on points (and goal difference) with the Swedish side – two behind the front-runners from Belgium. • Beşiktaş currently prop up the group table with four points, having collected just one from their past three fixtures – in a 1-1 draw on matchday four away to Genk, who had beaten them 4-2 in Istanbul a fortnight earlier, inflicting a second successive loss after they had gone down 2-0 at Malmö. A further defeat in Norway will knock out Beşiktaş. Previous meetings • Beşiktaş beat Sarpsborg 3-1 in Istanbul on the visitors' group stage bow, Dutchmen Ryan Babel and Jeremain Lens both finding the net. There had been no previous matches between the two clubs, nor between Sarpsborg and any other Turkish team. -

Statutes for Ballspielverein 09 E.V. Dortmund GENERAL Section 1 The

Statutes for Ballspielverein 09 e.V. Dortmund GENERAL Section 1 The club’s name, place of Business and colours Ballspielverein Borussia 09 e.V. Dortmund, founded on 19 December 1909, is based in Dortmund and is listed under Dortmund District Court’s Register of Associations. The club’s colours are black and yellow. Section 2 Purpose and functions (1) The purpose and function of the club is to promote sport. In particular, it seeks to promote sporting exercise and endeavour among its members, especially among adolescents, whereby the team sport of football is accorded a pre-eminent position within the club as the primary form of sport. The club remains strictly neutral with respect to religion and politics and rests upon a democratic foundation in all of its concerns. (2) The club also operates the following divisions: a) The Handball Division b) The Table Tennis Division c) The Borussia Dortmund Supporters Association (3) The club promotes the function of sport as a unifying element between nationalities, cultures, religions and social classes. It provides children, young persons and adults with a sporting home regardless of gender, skin colour, background, beliefs, social position or sexual identity. (4) Furthermore, the club also aims to promote art and culture. It is expected that the promotion of art and culture as stipulated in these Statutes will be realised through the establishment and operation of cultural bodies for the purpose of cultivating and passing on traditions, such as a collection of historical artefacts and documents which attest to the sporting and cultural significance of the club for the city of Dortmund and the region. -

U12 Hussitencup No. 1, Gr. a 10:30 Vfl Wolfsburg SV Werder

U12 Hussitencup No. 1, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 2, Gr. B 10:30 10:43 VfL Wolfsburg : SV Werder Bremen Hamburger SV : Hertha BSC Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. 3, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 4, Gr. B 10:56 11:09 1.FC Union Berlin : SV Babelsberg Dynamo Dresden : FC Hansa Rostock Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. 5, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 6, Gr. B 11:22 11:35 FSV Bernau : VfL Wolfsburg RB Leipzig : Hamburger SV Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. 7, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 8, Gr. B 11:48 12:01 SV Werder Bremen : 1.FC Union Berlin Hertha BSC : Dynamo Dresden Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. 9, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 10, Gr. B 12:14 12:27 SV Babelsberg : FSV Bernau FC Hansa Rostock : RB Leipzig Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. 11, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 12, Gr. B 12:40 12:53 1.FC Union Berlin : VfL Wolfsburg Dynamo Dresden : Hamburger SV Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. 13, Gr. A U12 Hussitencup No. 14, Gr. B 13:06 13:19 SV Babelsberg : SV Werder Bremen FC Hansa Rostock : Hertha BSC Goalscorers Goalscorers Made with passion by tournej Made with passion by tournej U12 Hussitencup No. -

2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Selling the People's Game Football's transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor State Veth, Karl Manuel Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Selling the People’s Game: Football's Transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States K. -

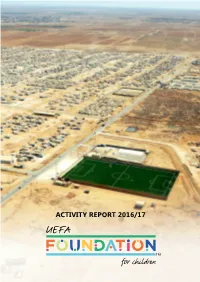

UEFA Foundation for Children Activity Report for 2016/17

ACTIVITY REPORT 2016/17 4 SOMMAIRE THE HEART OF THE FOUNDATION ÉDITORIAUX 6 2016 CALL FOR PROJECTS 12 2017 UEFA FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN AWARD le besoin, celui de convertir les valeurs Après une année de travail assidu EDITORIAL Tania Baima, Laure N’Singui-Lubanzadio, Cyril Pellevat, Pascal Torres 14 fondamentales de la civilisation euro- et d’objectifs ambitieux, un grand PHOTOS REFUGEES AND DISPLACED PEOPLE American Near East Refugee Aid péenne – la dignité humaine, la solidarité nombre de programmes humanitaires 03 20 27 Armenian Football Federation Barbara Čeferin EDITORIAL CAIS Associação de Solidariedade Social et l’espoir – en occasions d’améliorer et de développement sont aujourd’hui 20 Cancer Fund for Children Éditoriaux Billets de matches Chiffres clés Concordia la vie des enfants. menés par la Fondation dans le monde PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT Coopération Internationale pour les Équilibres Locaux Croatian Football Federation Diogenes entier. Nous continuerons à mobiliser Education for the Children 24 European Football for Development Network FC Barcelona Foundation L’UEFA, dont la Fondation est indépen- l’ensemble de la famille du football – les DISABILITY RESEARCH FedEx Football Federation of Ukraine dante, s’est engagée à lui verser une clubs, les associations nationales et les EDUCATION Football For All in Vietnam Football Union of Russia Another successful year of activities has come In May, the foundation’s board of trustees FundLife International to a close. It wascontribution a highly productive 12 monthsannuelle jusqu’en 2025. sponsorswelcomed four – new dans members, ce therebybut. inUn- simple ballon Icehearts of Finland for the UEFA Foundation for Children, a time creasing its representative nature and plu- 26 IMBEWU Instituto Fazer Acontecer in which we wereEn able outre, to continue des and capitaux de- importants ont peutrality. -

Dr. Robert Niemann

DR. ROBERT NIEMANN FOOTBALL-BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY, INVESTMENT Dr. Robert Niemann is an entrepreneur and media expert in international sports and entertainment. His complementary core competencies combine the areas of invest- ment and the worldwide marketing of TV, media and digital rights, personalities and advanced technology. The consulting and management of associations, leagues, clubs and athletes in international soccer belong to the special fields of Dr. Niemann. His professional career extends from C-level positions in large international media groups, tv-production companies and US film studios up to board and management positions at most renowned companies. Since 2010 Dr. Niemann is running his own company NIEMANN GmbH in Munich and also invests in selected projects. MARKETING PERSONALITY RIGHTS DIGITALIZATION OTT MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT FINANCING LECTURES SEMINARS / COACHING Sports Investment Personality Coaching • Digitization as growth driver for investments in • Personal individual coaching for athletes and individuals in sports and entertainment public life • Asset classes of sport investments: clubs, media rights, • Scientifically based personality analysis and review sponsoring, player transfers, stadiums, data, sports • Brand conception and definition of core attributes betting, merchandising • Design of a 360° brand around a personality • Various instruments of sport investment: shares, bonds, • Activation and marketing concept financing, private equity, mezzanine capital, SPAC, M&A, IPO Investment in Soccer • Identification -

2021 / BRAND AMBASSADORS Sabrina Filzmoser

2021 / BRAND AMBASSADORS Sabrina Filzmoser Country: Austria Profession: Judo Team: Austrian National Team Accomplishments: 3rd PLACE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP – 2010, 2005 1st PLACE EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP – 2011, 2008 2nd PLACE EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP – 2013, 2010 3rd PLACE EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP – 2013, 2007, 2006, 2005, 2003 Dominik Frodl Country: Czech Republic Profession: Ice Hockey Team: HC Škoda Plzeň Accomplishments: CZECH U18 BEST GAA (1.67) – 2013-2014 CZECH U20 BEST SVS% (.930) – 2015-2016 CZECH EXTRA LIGA BEST GAA (1.89) – 2018-2019 CZECH EXTRA LIGA MOST SHUTOUTS (7) – 2019-2020 CZECH EXTRA LIGA MOST WINS (29) – 2019-2020 Lukas Osladil Country: Czech Republic Profession: Bodybuilder Accomplishments: 4 TIMES NOMINEE FOR MR OLYMPIA 8th PLACE MR OLYMPIA – 2019 1st PLACE IN ARNOLD CLASSIC BRAZIL – 2017 Lukas Osladil Website Dmitri Kruglov Country: Estonia Profession: Soccer Team: FCI Levadia and the Estonian National Team Accomplishments: 1st PLACE ESTONIA NATIONAL LEAGUE (FCI TALLINN) – 2016 1st PLACE ESTONIA NATIONAL LEAGUE (LEVADIA TALLIN) – 2004, 2013, 2014 1st PLACE RUSSIAN NATIONAL LEAGUE (LOKOMOTIV MOSKVA) – 2005 Gerd Kanter Country: Estonia Profession: Discus Thrower Accomplishments: 1st PLACE IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE – 2012, 2013 3rd PLACE OLYMPIC GAME – 2012 1st PLACE OLYMPIC GAMES – 2008 1st PLACE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP – 2007 First BalanceTest Score: 7.8:1 Second BalanceTest Score: 2.8:1 Rain Josh Brandt Country: Estonia Profession: Pro Fighter First BalanceTest Score: 9.9:1 Second BalanceTest Score: 2.4:1 Read more about Rain Josh on our -

DIRECT-LIVE...Bundesliga Augsburg Vs Bayer Leverkusen En

bundesliga augsburg vs bayer leverkusen : liveStream, time GO LIVE http://nufilm.live/event/bundesliga-augsburg-vs-bayer-leverkusen CLICK HERE GO LIVE http://nufilm.live/event/bundesliga-augsburg-vs-bayer-leverkusen Bayer Leverkusen have never lost to Augsburg in 19 Bundesliga encounters. No match-up in the league has been played so many times without both teams recording at least one win. The latest updates for FC Augsburg - Bayer 04 Leverkusen on Matchday 3 in the 2021/2022 Bundesliga season - plus a complete list of all fixtures. FC Augsburg is going head to head with Bayer 04 Leverkusen starting on 28 Aug 2021 at 13:30 UTC at WWK ARENA stadium, Augsburg city, Germany. The match is a part of the Bundesliga. FC Augsburg played against Bayer 04 Leverkusen in 2 matches this season. Currently, FC Augsburg rank 8th, while Bayer 04 Leverkusen hold 3rd position. Bundesliga Augsburg vs Bayer Leverkusen match preview on 28.08.2021: team stats, match H2H, last results, lineups, injuries, standings, pre- match odds, over/under trend, BTTS trend Augsburg vs Bayer Leverkusen Odds - Saturday August 28 2021. Live betting odds and lines, betting trends, against the spread and over/under trends, injury reports and matchup stats for bettors. Odds/Point Spread: FC Augsburg (+290) Bayer Leverkusen (-118) Moussa Diaby and Bayer Leverkusen (1-1-0, 3rd in Bundesliga) travel to WWK Arena on Saturday where they'll take on FC Augsburg (0-1-1 Augsburg vs Leverkusen: FC Augsburg will be up against Bayer Leverkusen in the Matchday 3 of the Bundesliga 2021/22 season.