GENDER and MILITARISATION in KASHMIR By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INSURGENCY in the INDIAN NORTHEAST: STUDENT VOICES from KOLKATA India's Disputed Borderland Regions Consist of Kashmir In

INSURGENCY IN THE INDIAN NORTHEAST: STUDENT VOICES FROM KOLKATA India’s disputed borderland regions consist of Kashmir in the extreme north western part of the subcontinent and the north-east, located on the other side of the subcontinent in the extreme eastern sector of the Himalayas. A disputed territory is an area over which two or more actors (states or ethnic groups) claim sovereignty (Wolff, 2003:3). Since independence in 1947, from British colonial rule, India has had very problematic relations with both Kashmir and the Northeast, both of which have been classified as ‘disturbed areas’ by the New Delhi political establishment. Both regions have experienced strong secessionist movements that have tried to break away from the Indian union. ‘Secession is a bid for independence through the redrawing of a state’s geographical boundaries in order to exclude the territory that the seceding group occupies from the state’s sovereignty’ (Webb, 2012:471). Insurgent groups from both regions, Kashmir and the Indian northeast, do not seem to have a sense of one-ness with the rest of India or India proper. Also, in both regions, external forces have been strongly involved since independence e.g. Pakistan in Kashmir and China and Burma in the Indian north-eastern states. Out of the two disputed borderland regions, this paper will be focussing only on the Indian northeast. It is the aim of this paper to look into the many facets of the conflict in the Indian northeast and to especially focus on student voices. One reason why students have been chosen for purposes of this paper is because throughout the contemporary history of the Indian northeast especially with regard to Assam, students have been very active in putting their demands forward to the national Indian government and have been active in organising protest movements and causing political agitation. -

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

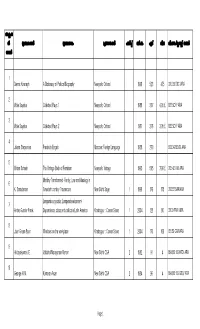

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

Use Bullets Against Stone-Pelters, Traitors: JK Minister

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com 3 FORECAST JAMMU Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 21-Apr 28.0 40.0 Partly cloudy sky in the morning hours becoming generally cloudy sky 22-Apr 26.0 38.0 hunderstorm with rain 23-Apr 24.0 37.0 Thunderstorm with rain 3 DAY'S FORECAST SRINAGAR Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 21-Apr 12.0 24.0 Thunderstorm with rain 22-Apr 11.0 22.0 Thunderstorm with rain 23-Apr 9.0 20.0 Thunderstorm with rain Minister asks for optimum utilization of northlinesPhoto exhibition on celebrating the JK Bank hires Delloitte as their Auqaf assets overhaul Consultants diversity inaugurated Minister of State for Hajj and Auqaf JK Bank today entered into an Speaker, J&K Legislative Assembly Syed Farooq Ahmad Andrabi today agreement with M/S Delloitte thereby Kavinder Gupta inaugurated a photo laid foundation for renovation and engaging them as their consultants for exhibition on the theme 'celebrating 3 repairs work of Qadeem Jamia providing consultancy services on diversity' organized by the Masjid Bahu Fort.... 4 Business Plan .... 5 INSIDE Department of ..... Vol No: XXII Issue No. 95 21.04.2017 (Friday) Daily Jammu Tawi Price ` 2/- Pages-12 Regd. No. JK|306|2014-16 What Azaadi? Use bullets against Officer 'saved lives' by tying man to Military cannot be subjected to jeep in Kashmir: Madhav FIR for its Operations: Army stone-pelters, traitors: JK minister NL CORRESPONDENT Kashmir or Manipur, we are said the current Kashmir boys. He also did not allow NEW DELHI, APR 20 facing the same local bias. -

Page-1Final.Qxd (Page 2)

daily Vol No. 53 No. 282 JAMMU, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2017 REGD.NO.JK-71/15-17 14 Pages ` 5.00 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/65 Vohra meets Rajnath 2 cops, OGW held for supplying arms to HM NEW DELHI, Oct 11: Jammu and Kashmir Governor N N Vohra today met Home Minister Rajnath Singh 2 Garud commandos, 2 militants killed and discussed with him various issues, including the security situation in the state. Fayaz Bukhari while another identified as which two militants identified place in which two militants During the 20-minute meet- Surjeet Miulind Khairum was as Nasrullah Mir alias Anna were killed and two IAF com- ing, the Governor briefed the SRINAGAR, Oct 11: Two seriously injured. The injured son of Nazir Ahmad Mir resi- mandos were killed. Home Minister about the pre- militants and two Indian Air dent of Mir Mohalla Verdi said that the militants vailing situation along the bor- Force (IAF) commandos were Hajin and foreign were involved in many attacks der with Pakistan, which has killed in an encounter in militant Ali Bai alias including killing of BSF Jawan been violating ceasefire regu- Bandipora district of North Maaz alias Abu Mohammad Ramzan alias larly, official sources said. Kashmir early today while Bakker were killed. rameez at his home, with knives The constitution of a study Police arrested two cops and Two AK riles, one and then fired indiscriminately, in which he was killed and his (Contd on page 4 Col 5) an Over Ground Worker pistol, 19 pistol (OGW) of militants for sup- rounds, one grenade, old aged father Ghulam Ahmad Singh takes over plying arms and ammunition two pouches and Parray, two elder brothers to Hizbul Mujahideen in other ammunition Mohammad Afzal Parray, Javid as GOC 16 Corps Shopian district of South was recovered from Ahmad Parray and paternal aunt Excelsior Correspondent Kashmir. -

Historical Places

Where to Next? Explore Jammu Kashmir And Ladakh By :- Vastav Sharma&Nikhil Padha (co-editors) Magazine Description Category : Travel Language: English Frequency: Twice in a Year Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Unlimited is the perfect potrait of the most beautiful place of the world Jammu, Kashmir&Ladakh. It is for Travelers, Tourism Entrepreneurs, Proffessionals as well as those who dream to travel Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh and have mid full of doubts. This is a new kind of travel publication which trying to promoting the J&K as well as Ladakh tourism industry and remove the fake potrait from the minds of people which made by media for Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh. Jammu Kashmir and ladakh Unlimited is a masterpiece, Which is the hardwork of leading Travel writters, Travel Photographer and the team. This magazine has covered almost every tourist and pilgrimage sites of Jammu Kashmir & Ladakh ( their stories, history and facts.) Note:- This Magazine is only for knowledge based and fact based magazine which work as a tourist guide. For any kind of credits which we didn’t mentioned can claim for credits through the editors and we will provide credits with description of the relevent material in our next magazine and edit this one too if possible on our behalf. Reviews “Kashmir is a palce where not even words, even your emotions fail to describe its scenic beauty. (Name of Magazine) is a brilliant guide for travellers and explore to know more about the crown of India.” Moohammed Hatim Sadriwala(Poet, Storyteller, Youtuber) “A great magazine with a lot of information, facts and ideas to do at these beautiful places.” Izdihar Jamil(Bestselling Author Ted Speaker) “It is lovely and I wish you the very best for the initiative” Pritika Kumar(Advocate, Author) “Reading this magazine is a peace in itself. -

Kashmir a PARADISE on EARTH Description

Kashmir A PARADISE ON EARTH Description: Emerald green meadows, majestic mountains, bewitching lakes and valleys… Nestling in the lap of the dazzling, snow-capped Himalayas, the Kashmir Valley is undoubtedly a jewel in India’s crown. This paradise on earth is indeed a nature lover’s wonderland. Srinagar: The state capital is situated at an altitude of 1730 m. above sea level. The city of Srinagar stretches along the bank of the Jhelum River, which is spanned by nine old and several other new bridges. Canals intersect the city and link the Jhelum with the spring-fed Dal Lake, which is divided by causeways into four parts-Gagribal, Lokutdal, Boddal and Nagin. Pahalgam: At the confluence of the streams flowing from the river Lidder and Sheshnag lake, Pahalgam was once a humble shepherd’s village with pristine beauty and breathtaking views. At an altitude of 2130 m. and 96 km from Srinagar, Pahalgam is Kashmir’s premier resort; cool even during peak summer. Gulmarg: At an altitude of 2730 m. and 56 km from Srinagar, Gulmarg is a huge cup-shaped meadow, lush and green, with slopes where the silence is broken only by the tinkle of cow-bells. All around are snow-capped mountains, and on a clear day you can see all the way to Nanga Parbat in one direction and Srinagar in another. Information: Eligibility: no age bar. Food: Wholesome and hygienic vegetarian food would be served. Jain Food will be available on prior request at resort/hotel but the same cannot be guaranteed during journey. Medical Facilities: Essential medical facilities in the form of first aid would be available throughout the journey and at resort/hotel. -

India's Child Soldiers

India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child A shadow report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers Published by: Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058 INDIA Tel/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] First published March 2013 ©Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2013 No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN : 978-81-88987-31-3 Suggested contribution Rs. 295/- Acknowledgement: This report is being published as a part of the ACHR’s “National Campaign for Prevention of Violence Against Children in Conflict with the Law in India” - a project funded by the European Commission under the European Instrument for Human Rights and Democracy – the European Union’s programme that aims to promote and support human rights and democracy worldwide. The views expressed are of the Asian Centre for Human Rights, and not of the European Commission. Asian Centre for Human Rights would also like to thank Ms Gitika Talukdar of Guwahati, a photo journalist, for the permission to use the photographs of the child soldiers. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Arrested and Charged in Coordinated Raids Across India

31 August 2018 India: Five human rights defenders arrested and charged in coordinated raids across India On 28 August 2018, five human rights defenders were arrested and several others’ residences, including Father Stan Swamy’s, were raided in a coordinated crackdown by Pune police in different parts of India. Sudha Bhadwaj, Vernon Gonsalves, Varavara Rao, Gautam Navlakha and Arun Ferreira were all arrested in different cities under a host of charges, including terrorism-related charges. Sudha Bhardwaj is a human rights lawyer, with a focus on protecting the rights of adivasi (indigenous) people in the state of Chattisgarh. She has acted as legal representation in several cases of extrajudicial executions of adivasis and has represented adivasis and activists before the National Human Rights Commission of India. She also serves as the General Secretary of the Chattisgarh People’s Union for Civil Liberties. Vernon Gonsalves is an academic and writer, who writes extensively on Dalit and adivasi rights, the conditions of prisons in India and the rights of prisoners. He has also advocated for scrapping the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, a draconian piece of anti-terror legislation with a wide ambit and vague concepts, which allows its misuse against academics, lawyers and human rights defenders. In recent times, it has been used repeatedly to target people expressing dissent. Varavara Rao is an acclaimed academic, well known for his progressive writings. He regularly takes part in various social activism activities and often speaks publicly on human rights issues. Gautam Navlakha is a human rights defender and journalist. He was the Secretary of the People’s Union for Democratic Rights, a non-governmental organisation committed to legally defending civil liberties and democratic rights by protecting, extending and helping implement fundamental rights as guaranteed in the Indian constitution. -

Better Economic Alternative for Rural Kashmir :By Mr. Riyaz Ahmed Wani

Better economic alternative for rural Kashmir :by Mr. Riyaz Ahmed Wani GENESIS OF ECONOMIC CRISIS IN J&K Post 1947, Kashmir economy had a cataclysmic start. The state embarked upon its development process by the enactment of Big Landed Estates Act 1949-50, a radical land redistribution measure which abolished as many as nine thousand Jagirs and Muafis. The 4.5 lac acres of land so expropriated was redistributed to tenants and landless. Land ceiling was fixed at 22.75 acres. This was nothing short of a revolutionary departure from a repressive feudal past. And significantly enough, it was preceded or followed by little or negligible social disturbance. This despite the fact that no compensation was paid to landlords. More than anything else, it is this measure which set the stage for new J&K economy. In the given circumstances, the land reforms proved sufficient to turn around the economic condition of the countryside with the hitherto tenants in a position to own land and cultivate it for themselves. However, the reforms though unprecedented in their nature and scale were not only pursued for their own sake but were also underpinned by an ambitious economic vision. Naya Kashmir, a vision statement of Shiekh Muhammad Abdullah, laid down more or less a comprehensive plan for a wholesome economic development of the state. But the dismissal of Shiekh Abdullah’s legitimately elected government in 1953 by the centre changed all that. The consequent uncertainty which lingers even now created an adhocist political culture animated more by vested interest than a commitment to the development of the state. -

'Growing up Under the Shadow of the Gun'

‘Growing up under the shadow of the gun’ Research on the lives of women who grew up with the realities of the Armed Force Special Powers Act in Kashmir. Name of student: D.S.C. Boerema Student number: 5710685 Date of Submission: 18-07-2018 University of Utrecht A Thesis submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Studies & Human Rights. Supervisor: prof. dr. ir. Georg Frerks Date of Submission: 18-07-2018 Programme trajectory: Research and thesis Writing (30ECT) Word count: 26000 Abstract Implemented in 1990, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act gives the Indian army blanket immunity to arrest, interrogate, kill and rape Kashmiri’s if they are considered a safety threat. At this moment seventy per cent of Kashmir’s population is under the age of thirty-five. This means that most of them have grown up knowing no other reality than that of living in a heavily securitized zone. This thesis is written based on the memories and experiences of thirty women who all come from Kashmir. Some of them were born just before 1990, most of them after this defining year in Kashmir history. Women’s voices are the most misunderstood and underreported in a conflict. This thesis aims to find an answer to how the securitization of Kashmir, through the AFSPA, has mobilized women to use public space as a tool for resistance in Srinagar. It finds that women mobilize to claim a space for their own identity as Kashmiri women, within a larger society that experiences an attack on its identity in the form of Indian occupation.