4 August 1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and the Constitutional Text John C

War and the Constitutional Text John C. Yoo∗ In a series of articles, I have criticized the view that the original under- standing of the Constitution requires that Congress provide its authorization before the United States can engage in military hostilities.1 This “pro- Congress” position ignores the constitutional text and structure, errs in in- terpreting the ratification history of the Constitution, and cannot account for the practice of the three branches of government. Instead of the rigid proc- ess advocated by scholars such as Louis Henkin, John Hart Ely, Louis Fisher, Michael Glennon, and Harold Koh,2 I have argued that the Constitu- tion creates a flexible system of war powers. That system provides the president with significant initiative as commander-in-chief, while reserving to Congress ample authority to check executive policy through its power of the purse. In this scheme, the Declare War Clause confers on Congress a ju- ridical power, one that both defines the state of international legal relations ∗ Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley School of Law (Boalt Hall) (on leave); Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, United States Department of Justice. The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of the Department of Justice. I express my deep appreciation for the advice and assistance of James C. Ho in preparing this response. Robert Delahunty, Jack Goldsmith, and Sai Prakash provided helpful comments on the draft. 1 See John C. Yoo, Kosovo, War Powers, and the Multilateral Future, 148 U Pa L Rev 1673, 1686–1704 (2000) (discussing the original understanding of war powers in the context of the Kosovo conflict); John C. -

Wwi 1914 - 1918

ABSTRACT This booklet will introduce you to the key events before and during the First World War. Taking place from 1914 – 1918, millions of people across the world lost their lives in what was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’. Fighting on this scale had never been seen before. The work in this booklet will help you understand why such a horrific conflict begun. Ms Marsh WWI 1914 - 1918 Year 8 History Why did the First World War begin? L.O: I can explain the causes of the First World War. 1. In what year did the war begin? 2. In what year did the war end? 3. How many years did it last? (Do now answers at end of booklet) The First World War begun in August 1914. It took the world by surprise, and seemed to happen overnight. In reality, tension between countries in Europe had been increasing for some years before. The final event that triggered war, the assassination of a young heir to the Austria – Hungary throne, demonstrates how this tension had been building. Europe in the early 20th century was a place where newly formed countries such as Italy started to challenge the dominance of countries with empires. An empire is when one country rules over others around the world. Some countries began to demand their independence and did not want to be ruled by an empire. The map opposite shows just how vast the empires of Europe were; Britain had control of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, East and South Africa and India. -

Timeline of Start Of

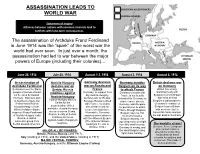

ASSASSINATION LEADS TO EUROPEAN ALLIED POWERS WORLD WAR CENTRAL POWERS Statement of Inquiry Alliances between nations with common interests lead to conflicts with long-term consequences. RUSSIA GERMANY GERMANY The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand FRANCE AUSTRIA- in June 1914 was the “spark” of the worst war the HUNGARY world had ever seen. In just over a month, the Bosnia assassination had led to war between the major OTTOMAN EMPIRE powers of Europe (including their colonies)… June 28, 1914 July 28, 1914 August 1-3, 1914 August 3, 1914 August 4, 1914 Assassination of Austria-Hungary Germany declares Germany invades Britain declares war Archduke Ferdinand declares war on war on Russia and Belgium on its way on Germany Serbia believes the Slavic Serbia; Russia France to attack France Britain has a long- people of Europe should mobilizes against Germany, to support their Germany’s border with standing treaty with Belgium in which Britain not be ruled by Austria- Austria-Hungary ally Austria-Hungary, France is too heavily Hungary. Bosnia is part declares war on Russia. defended for Germany to agreed to defend Austria-Hungary blames of Austria-Hungary, but Because Russia is allied attack France directly. Belgium’s independence. Serbia for the Serbia thinks Bosnia with France, Germany Germany asks Belgium Germany’s invasion of assassination of their should belong to them. also declares war on for permission to attack Belgium leaves Britain archduke. Austria-Hungary When Archduke (future France two days later. France through Belgium. with no choice but to declares war on Serbia. emperor) Franz-Ferdinand Meanwhile, Germany Belgium says no, but honor this treaty and join Russia, an ally of Serbia, of Austria-Hungary visits makes a secret alliance Germany invades the war against Germany. -

10 Downing Street

10 DOWNING STREET 8th June, 1981 "ANYONE FOR DENIS?" - SUNDAY, 12TH JULY 1981 AT 7.30 P.M. Thank you so much for your letter of 29th May. I reply to your numbered questions as follows:- Five (the Prime Minister, Mr. Denis Thatcher, Mr. Mark Thatcher, Jane and me.) In addition, there will be two (or possibly three) Special Branch Officers. None of these will be paying for tickets. No. but of course any Cabinet Minister is at liberty . to buy a ticket that evening, like anyone else, if he wishes to do so. I would not feel inclined to include any Opposition Member on the mailing list. No. The Prime Minister wi.11 be glad to have a photocall at 10 Downing Street at 6.45 p.m., when she would hand over cheques to representatives of the N.S.P.C.C. and of Stoke Mandeville. Who will these representatives be, please? The Prime Minister does not agree that Angela Thorne should wear the same outfit. The Prime Minister will be pleased to give a small reception for say sixty people. Would you please submit a list of names? I do not understand in what role it is suggested that Mr. Paul Raymond should attend the reception after the performance. By all means let us have a word about this on the telephone. Ian Gow Michael Dobbs, Esq, 10 DOWNING STREET Q4 Is, i ki t « , s 71 i 1-F Al 4-) 41e. ASO C a lie 0 A-A SAATCHI & SAATCHI GARLAND-CONIPTON LTD , \\ r MD/sap 29th May 1981 I. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

French Press, Public Opinion and the Murder of Franz Ferdinand In

French press, public opinion and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand (28 June-3 August 1914) How French society entered the Great war? Unlocking sources • The aim of this communication is quite simple: how new ways of getting access to digital contents (through technical process such as OCR and NER) give us the opportunity to understand how French society entered the First World War in August 1914? • Regarding this topic, I have studied both private archives and French press issues made available through the project Europeana 14-18 (chronologically from the 29 of June, the day after the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand , heir of the austro-hungarian monarchy in Sarajevo to the 3rd of August, the day of the declaration of war of Germany on France) • I have used two different technologies I will come back later on: the optical recognition of characters and the named entities recognition, a process we have developped thanks to another European project, Europeana Newspapers Unlocking sources • One of the main concern for me was also to assess the impact of the use of these automated processes applied to historical sources • This question is quite important as I strongly believe that the use of such technical process modify deeply our access and our understanding of historical sources (in other words how automated process lead to a new way of writing history) Starting point Emile Spring 1914 Starting point Letter sent to his family in law 31st of July 1914 French historiography • J-J Becker, How French entered the war, 1977) • If we consider the succession of events from the assassination of the archduke Franz-Ferdinand the 28th of June in Sarajevo to the declaration of war on France the 3rd of August, the point of view promoted by J.J. -

When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

WHEN DIPLOMATS FAIL: AOSTRIAN AND ROSSIAN REPORTING FROM BELGRADE, 1914 Barbara Jelavich The mountain of books written on the origins of the First World War have produced no agreement on the basic causes of this European tragedy. Their division of opinion reflects the situation that existed in June and July 1914, when the principal statesmen involved judged the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, and its consequences from radically different perspectives. Their basic misunderstanding of the interests and viewpoints 'of the opposing sides contributed strongly to the initiation of hostilities. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the importance of diplomatic reporting, particularly in the century before 1914 when ambassadors were men of influence and when their dispatches were read by those who made the final decisions in foreign policy. European diplomats often held strong opinions and were sometimes influenced by passions and. prejudices, but nevertheless throughout the century their activities contributed to assuring that this period would, with obvious exceptions, be an era of peace in continental affairs. In major crises the crucial decisions are always made by a very limited number of people no matter what the political system. Usually a head of state -- whether king, emperor, dictator, or president, together with those whom he chooses to consult, or a strong political leader with his advisers- -decides on the course of action. Obviously, in times of international tension these men need accurate information not only from their military staffs on the state of their and their opponent's armed forces and the strategic position of the country, but also expert reporting from their representatives abroad on the exact issues at stake and the attitudes of the other governments, including their immediate concerns and their historical background. -

To Declare War

TO DECLARE WAR J. GREGORY SIDAK* INTRODUCTION ................................................ 29 I. DID AMERICA'S ENTRY INTO THE PERSIAN GULF WAR REQUIRE A PRIOR DECLARATION OF WAR?................ 36 A. Overture to War: Are the PoliticalBranches Willing to Say Ex Ante What a "War" Is? ...................... 37 B. Is It a Political Question for the Judiciary to Issue a DeclaratoryJudgment Saying Ex Ante What Is or Will Constitute a "War"? .................................. 39 C. The Iraq Resolution of January 12, 1991 .............. 43 D. Why Do We No Longer Declare War When We Wage War? ................................................ 48 E. The President's War-Making Duties as Commander in Chief ................................................ 50 F. The Specious Dichotomy Between "General War" and Undeclared "'Limited War"........................... 56 II. THE COASE THEOREM AND THE DECLARATION" OF WAR: POLITICAL ACCOUNTABILITY AS A NORMATIVE PRINCIPLE FOR IMPLEMENTING THE SEPARATION OF POWERS ........ 63 A. Coasean Trespasses and Bargains Between the Branches of Government ....................................... 64 B. PoliticalAccountability, Agency Costs, and War ........ 66 C. American Sovereignty and the United Nations .......... 71 III. THE ACCOUNTABLE FORMALISM OF DECLARING WAR: LESSONS FROM THE DECLARATION OF WAR ON JAPAN .... 73 A. Provocation and Culpability: Is America Initiating War or Is Pre-Existing War "Thrust Upon" It? ............. 75 B. The Objectives of War: The President'sLegislative Role as Recommender of War .............................. 79 * A.B. 1977, A.M., J.D. 1981, Stanford University. Member of the California and District of Columbia Bars. In writing this Article, I have benefitted from the comments and protests of Gary B. Born, L. Gordon Crovitz, John Hart Ely, Daniel A. Farber, John Ferejohn, Michael J. Glennon, Stanley Hauerwas, Geoffrey P. -

Chapter 23: War and Revolution, 1914-1919

The Twentieth- Century Crisis 1914–1945 The eriod in Perspective The period between 1914 and 1945 was one of the most destructive in the history of humankind. As many as 60 million people died as a result of World Wars I and II, the global conflicts that began and ended this era. As World War I was followed by revolutions, the Great Depression, totalitarian regimes, and the horrors of World War II, it appeared to many that European civilization had become a nightmare. By 1945, the era of European domination over world affairs had been severely shaken. With the decline of Western power, a new era of world history was about to begin. Primary Sources Library See pages 998–999 for primary source readings to accompany Unit 5. ᮡ Gate, Dachau Memorial Use The World History Primary Source Document Library CD-ROM to find additional primary sources about The Twentieth-Century Crisis. ᮣ Former Russian pris- oners of war honor the American troops who freed them. 710 “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” —Winston Churchill International ➊ ➋ Peacekeeping Until the 1900s, with the exception of the Seven Years’ War, never ➌ in history had there been a conflict that literally spanned the globe. The twentieth century witnessed two world wars and numerous regional conflicts. As the scope of war grew, so did international commitment to collective security, where a group of nations join together to promote peace and protect human life. 1914–1918 1919 1939–1945 World War I League of Nations World War II is fought created to prevent wars is fought ➊ Europe The League of Nations At the end of World War I, the victorious nations set up a “general associa- tion of nations” called the League of Nations, which would settle interna- tional disputes and avoid war. -

The Diplomatic Battle for the United States, 1914-1917

ACQUIRING AMERICA: THE DIPLOMATIC BATTLE FOR THE UNITED STATES, 1914-1917 Presented to The Division of History The University of Sheffield Fulfilment of the requirements for PhD by Justin Quinn Olmstead January 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1: Pre-War Diplomacy 29 A Latent Animosity: German-American Relations 33 Britain and the U.S.: The Intimacy of Attraction and Repulsion 38 Rapprochement a la Kaiser Wilhelm 11 45 The Set Up 52 Advancing British Interests 55 Conclusion 59 2: The United States and Britain's Blockade 63 Neutrality and the Declaration of London 65 The Order in Council of 20 August 1914 73 Freedom of the Seas 83 Conclusion 92 3: The Diplomacy of U-Boat Warfare 94 The Chancellor's Challenge 96 The Chancellor's Decision 99 The President's Protest 111 The Belligerent's Responses 116 First Contact: The Impact of U-Boat Warfare 119 Conclusion 134 4: Diplomatic Acquisition via Mexico 137 Entering the Fray 140 Punitive Measures 145 Zimmerman's Gamble 155 Conclusion 159 5: The Peace Option 163 Posturing for Peace: 1914-1915 169 The House-Grey Memorandum 183 The German Peace Offer of 1916 193 Conclusion 197 6: Conclusion 200 Bibliography 227 Introduction Shortly after war was declared in August 1914 the undisputed leaders of each alliance, Great Britain and Gennany, found they were unable to win the war outright and began searching for further means to secure victory; the fonnation of a blockade, the use of submarines, attacking the flanks (Allied attacks in the Balkans and Baltic), Gennan Zeppelin bombardment of British coastal towns, and the diplomatic search for additional allies in an attempt to break the stalemate that had ensued soon after fighting had commenced. -

How Did the First World War Start?

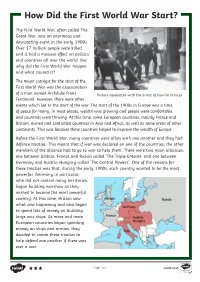

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

Decisions for War, 1914–1917

P1: JZZ 0521836794pre CB775-Hamilton-v1 September 22, 2004 9:57 Decisions for War, 1914–1917 Richard F. Hamilton The Ohio State University Holger H. Herwig University of Calgary v P1: JZZ 0521836794pre CB775-Hamilton-v1 September 22, 2004 9:57 PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Richard F. Hamilton & Holger H. Herwig 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typefaces Plantin 10/13 pt. and Hiroshige System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Decisions for War, 1914–1917 / Richard F. Hamilton, Holger H. Herwig. p. cm. Abridgment of: The origins of World War I / edited by Richard F. Hamilton, Holger H. Herwig. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-521-83679-4 – ISBN 0-521-54530-7 (pbk.) 1. World War, 1914–1918 – Causes. 2. World War, 1914–1918 – Diplomatic history. I. Hamilton, Richard F. II. Herwig, Holger H. III. Origins of World War I.