Reasons for Unsatisfactory Participation in the Army Reserve: a Socialization Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sergeant First Class V. Terrance Scott Senior Military Science Instructor

Sergeant First Class V. Terrance Scott Senior Military Science Instructor University of Louisiana at Lafayette Sergeant First Class Terrance Scott entered the U.S. Army in January 1998. He attended Infantry One Station Unit Training (OSUT) at Fort Benning, Georgia. Sergeant First Class Scott’s first duty station was at Fort Riley, KS where he served as an Infantryman. Sergeant First Class Scott has served in numerous Mechanized Infantry Units, including 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division; 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division; 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division and 172d Infantry Brigade. Sergeant First Class Scott has served in all leadership positions from Team leader to Platoon Sergeant. Sergeant First Class Scott is a graduate of all levels of the Noncommissioned Officer Education System from the Professional Leadership and Development Course to the Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course. Sergeant First Class Scott’s other military training includes the Joint Firepower Control Course, Equal Opportunity Leaders Course, Instructor Training Course, and Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle System Master Gunner Course. Sergeant First Class Scott’s notable awards include the Bronze Star Medal (2d oak leaf cluster), Meritorious Service medal, Army Commendation Medal (4th Oak Leaf Cluster), Army Achievement Medal (5th Oak Leaf Cluster), the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, and the Expert Infantryman’s Badge. He is also a recipient of the Order of St. Maurice Medal (Centurion). Sergeant First Class Scott has participated in three tours in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom, and one tour in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Sergeant First Class Scott is currently pursuing his Bachelor of Arts in Theology from Liberty University. -

America's Military Reserve in the All-Volunteer Era: from Strategic To

America’s Military Reserve in the All-Volunteer Era: From Strategic to Operational Adapted from remarks by Maj. Gen. Jeffrey E. Phillips, U.S. Army (Ret.), at the March 28 All- Volunteer Force Forum Conference 2019, Angelo State University, San Angelo, Texas Good afternoon and thank you for the invitation to once again be in my adopted Lone Star State, whose beloved name, as all who have lived here know, is spelled without an “A” – Tex-Iss. My friend Maj. Gen. Denny Laich [who had spoken earlier in the conference] has occupied a leading role in the All-Volunteer Force reality show; his work on the topic defines the argument that the AVF is inadequate for the nation’s future – and that now is the time to seriously explore what we should do about the situation. We owe him our thanks for his dedication to the continued security of our nation and the well- being of those who serve in our military. The Pentagon, in its November 2018 end-of-year report on recruiting and retention, disclosed some deficiencies that reinforce any perception that the all-volunteer force is in trouble. The U.S. Army’s accessions were nearly 7,000 under its already reduced annual goal. Neither the Army National Guard nor the Army Reserve made their recruiting goal – the Army Reserve missing by nearly 30 percent. None of the three made their number. The Air National Guard and the Navy Reserve also failed to make their recruiting goals. DoD officials on a budget conference call earlier this month explained that increased enlistment bonuses, more and better advertising, better coordination of marketing, and more and better recruiting would make the difference. -

Military Ranks

WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 ABSTRACT WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 Copyright by Lindsay P. Cohn 2007 Abstract Contemporary militaries depend on volunteer soldiers capable of dealing with advanced technology and complex missions. An important factor in the successful recruiting, retention, and employment of quality personnel is the set of personnel policies which a military has in place. It might be assumed that military policies on personnel derive solely from the functional necessities of the organization’s mission, given that the stakes of military effectiveness are generally very high. Unless the survival of the state is in jeopardy, however, it will seek to limit defense costs, which may entail cutting into effectiveness. How a state chooses to make the tradeoffs between effectiveness and economy will be subject to influences other than military necessity. -

State Defense Force Times

State Defense Force Times and rescue efforts, provided medical services, and distributed food and water to hurricane victims. SGAUS is composed of over 3,000 soldiers throughout the 50 states and several territories, and over 570 attended the largest SGAUS Conference in its history. The annual conference provides opportunities for soldiers to obtain training in best practices in their specialties including communications, engineering, law, chaplain services, search and rescue, public affairs, and coordination with the United States Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Organized as a military force, each SDF reports to the state’s governor through the adjutant general, and best practices and training are developed through SGAUS and disseminated through the conference. SFC Patricia Isenberg of the South Carolina State Guard leads the way at the Hurricane Hike at the 2017 SGAUS Annual Conference in Myrtle Beach, SouthSpring Carolina. (Photo: – Summer Ms. Ronnie Berndt of2018 Hickory, North Carolina) The SGAUS Conference concluded on 23 September 2017 with its annual banquet. The South Carolina State Guard hosted the annual Keynoting the conference was former South conference of the State Guard Association of the Carolina Congressman Jim DeMint. United States (SGAUS) from September 21 – 23, 2017. SGAUS, the professional association of A Message from the Editor… State Defense Forces (SDF), provides organizational and training information for the Articles and images for the SDF Times are state militias organized under Title 10 of the welcome. Please send all articles to CPT (TN) United States Federal Code. Under Title 10 each Steven Estes at: state may organize a military force to respond to emergencies such as the recent Harvey and Irma [email protected]. -

Army Abbreviations

Army Abbreviations Abbreviation Rank Descripiton 1LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1SG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST BGLR FIRST BUGLER 1ST COOK FIRST COOK 1ST CORP FIRST CORPORAL 1ST LEADER FIRST LEADER 1ST LIEUT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST LIEUT ADC FIRST LIEUTENANT AIDE-DE-CAMP 1ST LIEUT ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT ASST SURG FIRST LIEUTENANT ASSISTANT SURGEON 1ST LIEUT BN ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT BATTALION ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT REGTL QTR FIRST LIEUTENANT REGIMENTAL QUARTERMASTER 1ST LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST MUS FIRST MUSICIAN 1ST OFFICER FIRST OFFICER 1ST SERG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST SGT FIRST SERGEANT 2 CL PVT SECOND CLASS PRIVATE 2 CL SPEC SECOND CLASS SPECIALIST 2D CORP SECOND CORPORAL 2D LIEUT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2D SERG SECOND SERGEANT 2LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2ND LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 3 CL SPEC THIRD CLASS SPECIALIST 3D CORP THIRD CORPORAL 3D LIEUT THIRD LIEUTENANT 3D SERG THIRD SERGEANT 3RD OFFICER THIRD OFFICER 4 CL SPEC FOURTH CLASS SPECIALIST 4 CORP FOURTH CORPORAL 5 CL SPEC FIFTH CLASS SPECIALIST 6 CL SPEC SIXTH CLASS SPECIALIST ACTG HOSP STEW ACTING HOSPITAL STEWARD ADC AIDE-DE-CAMP ADJT ADJUTANT ARMORER ARMORER ART ARTIF ARTILLERY ARTIFICER ARTIF ARTIFICER ASST BAND LDR ASSISTANT BAND LEADER ASST ENGR CAC ASSISTANT ENGINEER ASST QTR MR ASSISTANT QUARTERMASTER ASST STEWARD ASSISTANT STEWARD ASST SURG ASSISTANT SURGEON AUX 1 CL SPEC AUXILARY 1ST CLASS SPECIALIST AVN CADET AVIATION CADET BAND CORP BAND CORPORAL BAND LDR BAND LEADER BAND SERG BAND SERGEANT BG BRIGADIER GENERAL BGLR BUGLER BGLR 1 CL BUGLER 1ST CLASS BLKSMITH BLACKSMITH BN COOK BATTALION COOK BN -

Strength Management UNITED STATES CORPS of CADETS

Strength Management UNITED STATES CORPS OF CADETS TACTICAL NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICER PROGRAM Duty Description The Tactical Non-Commissioned Officer is the senior NCO and an essential developer of leaders for a company of cadets at the United States Military Academy. They will exemplify the high standards that are expected of the NCO Corps. The Tactical NCO is the first senior NCO that will have great influence over cadets; he/she must be in the top 10% of the NCO Corps. Daily duties and scope; First Sergeant for cadet company, United States Corps of Cadets; responsible for the health, welfare, and discipline of 125 future officers; counsels, trains, and develops cadet Corporals and Sergeants on all aspects of Army operations from company to brigade level; teaches and supervises Drill and Ceremony; monitors and conducts military training and the inspection of company areas and formations; assists in the overall development of the cadets to assume the position of Platoon Leader upon graduation from the United States Military Academy. He or she will work in a Tactical team with a Captain or Major to establish a proper command climate within their respective companies; also assist each cadet in balancing and integrating the requirements of physical, military, academic and moral-ethical programs. Qualifications The basic criteria for this assignment are: • Have a strong desire to serve in a critical position at USMA and a strong desire to prepare young individuals to assume leadership roles as officers in the United States military • Sergeant -

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract mostly from FM 3-21.8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad , but it also includes references from other FMs. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-TC. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. CHAPTER 1 - DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................... 2 CHAPTER 2 - COMMAND AND CONTROL.............................................................. 6 SECTION I – TROOP LEADING PROCEDURES .................................................. 6 SECTION II – RISK MANAGEMENT ..................................................................... 9 SECTION III - ORDERS ........................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 3 – OPERATIONS ..................................................................................... 14 SECTION I – FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION ....................................... 14 SECTION II – RANGE CARDS AND SECTOR SKETCHES ............................. 16 SECTION III - MOVEMENT ................................................................................... 25 SECTION IV - COMMUNICATION ....................................................................... 27 SECTION V - REPORTS ......................................................................................... -

The Noncommissioned Officer Corps on Leadership, the Army, and America; and the Noncommissioned Officer Corps on Training, Cohesion, and Combat (1998 )

2016 Reprint, with Minor Changes IMCEN Books Available Electronically, as of September 2001 (Before the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks on New York and the Pentagon, September 11, 2001) The Chiefs of Staff, United States Army: On Leadership and The Profession of Arms (2000). Thoughts on many aspects of the Army from the Chiefs of Staff from 1979–1999: General Edward C. Meyer, 1979–1983; General John A. Wickham, 1983–1987; General Carl E. Vuono, 1987–1991; General Gordon R. Sullivan, 1991–1995; and General Dennis J. Reimer, 1995–1999. Subjects include leadership, training, combat, the Army, junior officers, noncommissioned officers, and more. Material is primarily from each CSA’s Collected Works, a compilation of the Chief of Staff’s written and spoken words including major addresses to military and civilian audiences, articles, letters, Congressional testimony, and edited White Papers. [This book also includes the 1995 IMCEN books General John A. Wickham, Jr.: On Leadership and The Profession of Arms, and General Edward C. Meyer: Quotations for Today’s Army.] Useful to all members of the Total Army for professional development, understanding the Army, and for inspiration. 120 pages. The Sergeants Major of the Army: On Leadership and The Profession of Arms (1996, 1998). Thoughts from the first ten Sergeants Major of the Army from 1966–1996. Subjects include leadership, training, combat, the Army, junior officers, noncommissioned officers, and more. Useful to all officers and NCOs for professional development, understanding the Army, and for inspiration. Note: This book was also printed in 1996 by the AUSA Institute of Land Warfare. 46 pages. -

AR 600-20. Army Command Policy

Army Regulation 600 – 20 Personnel-General Army Command Policy Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 24 July 2020 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 600 – 20 Army Command Policy This administrative revision, dated 4 February 2021— o References DODD 1350.2 (para 6–9). o Removes appendix (app Q). This administrative revision, dated 1 September 2020— o Updates information (table 1–1). This administrative revision, dated 30 July 2020— o Updates information (fig 2–5). This major revision, dated 24 July 2020— o Adds reference to DoDI 1342.22 which now serves as the primary source of Family readiness policy guidance (title page). o Adds and/or updates responsibilities for the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Installations, Environment and Energy); Deputy Chief of Staff, G–9; Commanding General, U.S. Army Materiel Command; and the Commanding General, U.S. Army Installation Management Command (paras 1–4b, 1–4f, 2–5b, 5–2b, 7–5d). o Requires command leadership to treat Soldiers and Department of the Army Civilians with dignity and respect at all times (para 1–6c). o Clarifies the written abbreviation for the grade of “Specialist” (table 1 – 1, note 5). o Updates roles and responsibilities for command of installations (para 2–5b). o Clarifies policy on assumptions of command during the temporary absence of the commander (paras 2–9a(3), 2– 9d, 2 – 10, and 2 – 12). o Adds policy for command of installations, activities, and units on Joint bases (para 2 – 6). o Clarifies policy on the role of the reviewing commander regarding designation of junior in the same grade to command (para 2–8c). -

Guidance Concerning Selecting Duty Positions for SY 2020-21

Guidance Concerning Selecting Duty Positions for SY 2020-21 - We are starting the leadership selection process in preparation for next school year. The paragraphs below outline how students will inform the instructors of the duty positions in which they are interested for School Year 2020-21. - All returning cadets will complete the Cadet Leadership Application Form. The form is due to your primary Instructor electronically NLT 17 April (Friday). - Cadets who are interested in the most senior positions in the battalion will also complete the Senior Leadership Position Application and sign up for a Leadership Board time. The senior leader packets will be sent to COL Kardos by 24 April. Leadership boards will be held during 30 Apr- May 5. - Review what positions fall into each category on the third page of this document. - The Battalion Command Group and Primary Staff Officers will be selected and announced following the senior leader boards. We will tentatively fill other positions and finalize those in the fall. Most will not be announced until then. - Due to the lockdown, we will not be able to give volunteers the opportunity to serve as assistants in the staff sections before the end of the school year. However, we may be able to get cadets experience in this work during the summer, if the lockdown is lifted by then. Therefore, cadets should indicate if they are interested in helping on the staff by circling those positions on their application form. This could give you a better chance of getting one of those positions and moving up in rank. -

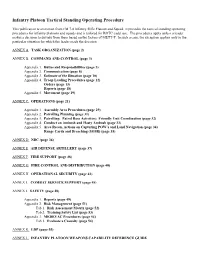

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract from FM 7-8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-T. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. ANNEX A. TASK ORGANIZATION (page 2) ANNEX B. COMMAND AND CONTROL (page 3) Appendix 1. Duties and Responsibilities (page 5) Appendix 2. Communication (page 8) Appendix 3. Estimate of the Situation (page 10) Appendix 4. Troop Leading Procedures (page 12) Orders (page 13) Reports (page 18) Appendix 5. Movement (page 19) ANNEX C. OPERATIONS (page 21) Appendix 1. Assembly Area Procedures (page 29) Appendix 2. Patrolling Planning (page 31) Appendix 3. Patrolling: Patrol Base Activities; Friendly Unit Coordination (page 32) Appendix 4. Conduct an Ambush and Hasty Ambush (page 33) Appendix 5. Area Recon, Actions on Capturing POW’s and Land Navigation (page 34) Range Cards and Breaching (SOSR) (page 35) ANNEX D. NBC (page 36) ANNEX E. AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY (page 37) ANNEX F. FIRE SUPPORT (page 38) ANNEX G. FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION (page 40) ANNEX H OPERATIONAL SECURITY (page 43) ANNEX I. COMBAT SERVICE SUPPORT (page 45) ANNEX J. SAFETY (page 48) Appendix 1. Reports (page 49) Appendix 2. Risk Management (page 51) Tab 1. Risk Assessment Matrix (page 52) Tab 2. Training Safety List (page 53) Appendix 3. -

Combat Engineer of the Wehrmacht Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GERMAN PIONIER 1939-45 : COMBAT ENGINEER OF THE WEHRMACHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gordon L. Rottman | 64 pages | 01 Jun 2010 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781846035784 | English | New York, United Kingdom German Pionier 1939-45 : Combat Engineer of the Wehrmacht PDF Book French- and Italian-made canned meat was also issued. Prussia and in Westphalia. The title is somehow misleading--most of equipment and weapons are described in text only very briefly and not illustrated properly with photos or drawings, apart from maybe artillery pieces. In both German and English, this book is one of the "classics" and also a good reference work on the unit. Stock photo. Back to home page. Pioneer training battalions Pioneer troops Railway pioneer training companies Railway pioneer troops Reconnaissance mounted troops Reconnaissance motorized troops Security troops Signals training regiment Signals troops Smoke training units Smoke troops Nebeltruppen Specialist officers Staff military Authority of the Reichsprotektor Supply officers Technical officers Transport supply officer Transport training units Transport troops Veterinary officers and NCOs Veterinary troops Kriegsakademie War academy War college. Power saws were essential as local forests were the main source of construction materials. About this Product. The effects would colour postwar European history for the next 50 years. Advertise Here. In no other country has camouflaged clothing been so extensively used, and in such great diversity of patterns and styles, as in Germany. The Pioniere are carrying their equipment over their shoulders, which was the only solution possible at this early stage of the river crossing. When hostilities commenced, the operational or fighting sections of the high command accompanied the Field Army, leaving behind in Germany the officers and the organization of the Replacement Army.