Volume 13, Issue 1 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices

centre for military studies university of copenhagen An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices 2012 This analysis is part of the research-based services for public authorities carried out at the Centre for Military Studies for the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. Its purpose is to analyse the conditions for Danish security policy in order to provide an objective background for a concrete discussion of current security and defence policy problems and for the long-term development of security and defence policy. The Centre for Military Studies is a research centre at the Department of —Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. At the centre research is done in the fields of security and defence policy and military strategy, and the research done at the centre forms the foundation for research-based services for public authorities for the Danish Ministry of Defence and the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. This analysis is based on research-related method and its conclusions can —therefore not be interpreted as an expression of the attitude of the Danish Government, of the Danish Armed Forces or of any other authorities. Please find more information about the centre and its activities at: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. References to the literature and other material used in the analysis can be found at http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. The original version of this analysis was published in Danish in April 2012. This version was translated to English by The project group: Major Esben Salling Larsen, Military Analyst Major Flemming Pradhan-Blach, MA, Military Analyst Professor Mikkel Vedby Rasmussen (Project Leader) Dr Lars Bangert Struwe, Researcher With contributions from: Dr Henrik Ø. -

Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers

January 2016 Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France, Daniele Fattibene Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France and Daniele Fattibene Contributors: Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, FOI Marie-Louise Chagnaud, SWP Olivier De France, IRIS Thanos Dokos, ELIAMEP Daniele Fattibene, IAI Niklas Granholm, FOI John Louth, RUSI Alessandro Marrone, IAI Jean-Pierre Maulny, IRIS Francesca Monaco, IAI Paola Sartori, IAI Torben Schütz, SWP Marcin Terlikowski, PISM 1 Index Executive summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 List of abbreviations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Chapter 1 - Defence spending in Europe in 2016 --------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.1 Bucking an old trend ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2 Three scenarios ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 1.3 National data and analysis ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.1 Central and Eastern Europe -------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.2 Nordic region -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Vs - Nur Für Den Dienstgebrauch

VS - NUR FÜR DEN DIENSTGEBRAUCH NATO UNCLASSIFIED NATO UNCLASSIFIED Foreword The term “counterinsurgency” (COIN) is an The document is divided into three parts: emotive subject in Germany. It is generally • Part A provides the basic conceptual accepted within military circles that COIN is an framework as needed to give a better interagency, long-term strategy to stabilise a crises understanding of the broader context. It region. In this context fighting against insurgents specifically describes the overall interagency is just a small part of the holistic approach of approach to COIN. COIN. Being aware that COIN can not be achieved successfully by military means alone, it • Part B shifts the focus to the military is a fundamental requirement to find a common component of the overall task described sense and a common use of terms with all civil previously. actors involved. • Part C contains some guiding principles to However, having acknowledged an Insurgency to stimulate discussions as well as a list of be a group or movement or as an irregular activity, abbreviations and important reference conducted by insurgents, most civil actors tend to documents. associate the term counterinsurgency with the combat operations against those groups. As a The key messages of the “Preliminary Basics for the Role of the Land Forces in COIN“ are: result they do not see themselves as being involved in this fight. For that, espescially in • An insurgency can not be countered by Germany, the term COIN has been the subject of military means alone. much controversy. • Establishing security and state order is a long- Germany has resolved this challenge with two term, interagency and usually multinational steps. -

Air Defence in Northern Europe

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES AIR DEFENCE IN NORTHERN EUROPE Heikki Nikunen National Defence College Helsinki 1997 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Pekka Sivonen, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Erkki Nordberg, Defence Staff Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 10 AIR DEFENCE IN NORTHERN EUROPE Heikki Nikunen National Defence College Helsinki 1997 ISBN 951-25-0873-7 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1997: National Defence College All rights reserved Oy Edita Ab Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1997 INTRODUCTION The historical progress of air power has shown a continuous rising trend. Military applications emerged fairly early in the infancy of aviation, in the form of first trials to establish the superiority of the third dimension over the battlefield. Well- known examples include the balloon reconnaissance efforts made in France even before the birth of the aircraft, and it was not long before the first generation of flimsy, underpowered aircraft were being tested in a military environment. The Italians used aircraft for reconnaissance missions at Tripoli in 1910-1912, and the Americans made their first attempts at taking air power to sea as early as 1910-1911. -

23. Baltic Perspectives on the European Security and Defence Policy

23. Baltic perspectives on the European Security and Defence Policy Elzbieta Tromer I. Introduction Given the choice between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Euro- pean Security and Defence Policy as providers of their national security, the Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—look to the USA. One reason is their perception of Russia as a source of instability. Another is their lack of con- fidence in the ability of the ESDP to deal with present-day threats. Although these three states are eager to be ‘normal’ members of the European Union and thus to join in its initiatives, their enthusiasm for the EU’s development of its own military muscle is lukewarm. An EU with some military capability but without the USA’s military strength and leadership holds little promise for them. Since the ESDP vehicle is already on the move, the Baltic states see their main function as ensuring coordination between the ESDP and NATO. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania want to be ‘Atlanticists from within the ESDP’.1 The Baltic states see themselves as exposed to challenges similar to those confronting the Nordic countries: notably the challenge of the new transatlantic dynamic, which makes it almost impossible to avoid taking sides between the US and Europe on an increasing range of global and specific issues. Being torn in this way is bound to be especially painful for Scandinavian [and Baltic] societies which have strong ties of history, culture and values with both sides of the Atlantic, and which in strategic terms are relatively dependent both on American military and European economic strength.2 The Nordic countries are seen by the Baltic states as allies in this context. -

Switzerland 4Th Periodical Report

Strasbourg, 15 December 2009 MIN-LANG/PR (2010) 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fourth Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter SWITZERLAND Periodical report relating to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages Fourth report by Switzerland 4 December 2009 SUMMARY OF THE REPORT Switzerland ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Charter) in 1997. The Charter came into force on 1 April 1998. Article 15 of the Charter requires states to present a report to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe on the policy and measures adopted by them to implement its provisions. Switzerland‘s first report was submitted to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in September 1999. Since then, Switzerland has submitted reports at three-yearly intervals (December 2002 and May 2006) on developments in the implementation of the Charter, with explanations relating to changes in the language situation in the country, new legal instruments and implementation of the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers and the Council of Europe committee of experts. This document is the fourth periodical report by Switzerland. The report is divided into a preliminary section and three main parts. The preliminary section presents the historical, economic, legal, political and demographic context as it affects the language situation in Switzerland. The main changes since the third report include the enactment of the federal law on national languages and understanding between linguistic communities (Languages Law) (FF 2007 6557) and the new model for teaching the national languages at school (—HarmoS“ intercantonal agreement). -

Switzerland1

YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW - VOLUME 14, 2011 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS SWITZERLAND1 Contents Multilateral Initiatives — Foreign Policy Priorities .................................................................. 1 Multilateral Initiatives — Human Security ................................................................................ 1 Multilateral Initiatives — Disarmament and Non-Proliferation ................................................ 2 Multilateral Initiatives — International Humanitarian Law ...................................................... 4 Multilateral Initiatives — Peace Support Operations ................................................................ 5 Multilateral Initiatives — International Criminal Law .............................................................. 6 Legislation — Implementation of the Rome Statute ................................................................. 6 Cases — International Crimes Trials (War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity, Genocide) .... 12 Cases — Extradition of Alleged War Criminal ....................................................................... 13 Multilateral Initiatives — Foreign Policy Priorities Swiss Federal Council, Foreign Policy Report (2011) <http://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/home/doc/publi/ppol.html> Pursuant to the 2011 Foreign Policy Report, one of Switzerland’s objectives at institutional level in 2011 was the improvement of the working methods of the UN Security Council (SC). As a member of the UN ‘Small 5’ group, on 28 March 2012, the Swiss -

An Unfinished Debate on NATO's Cold War Stay-Behind Armies

The British Secret Service in Neutral Switzerland: An Unfinished Debate on NATO’s Cold War Stay-behind Armies DANIELE GANSER In 1990, the existence of a secret anti-Communist stay-behind army in Italy, codenamed ‘Gladio’ and linked to NATO, was revealed. Subsequently, similar stay-behind armies were discovered in all NATO countries in Western Europe. Based on parliamentary and governmental reports, oral history, and investigative journalism, the essay argues that neutral Switzerland also operated a stay-behind army. It explores the role of the British secret service and the reactions of the British and the Swiss governments to the discovery of the network and investigates whether the Swiss stay-behind army, despite Swiss neutrality, was integrated into the International NATO stay-behind network. INTRODUCTION During the Cold War, secret anti-Communist stay-behind armies existed in all countries in Western Europe. Set up after World War II by the US foreign intelligence service CIA and the British foreign intelligence service MI6, the stay-behind network was coordinated by two unorthodox warfare centres of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the ‘Clandestine Planning Committee’ (CPC) and the ‘Allied Clandestine Committee’ (ACC). Hidden within the national military secret services, the stay-behind armies operated under numerous codenames such as ‘Gladio’ in Italy, ‘SDRA8’ in Belgium, ‘Counter-Guerrilla’ in Turkey, ‘Absalon’ in Denmark, and ‘P-26’ in Switzerland. These secret soldiers had orders to operate behind enemy lines in -

'Mau Mau' and Colonialism in Kenya

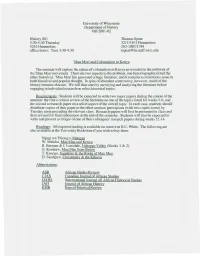

University of Wisconsin Department of History Fall2001-02 History 861 Thomas Spear 3:30-5:30 Thursday 3211/5101 Humanities 5245 Humanities 263-1807/1784 office hours: Tues 3:30-4:30 tspear@facstaff. wisc.edu 'Mau Mau' and Colonialism in Kenya The seminar will explore the nature of colonialism in Kenya as revealed in the outbreak of the 'Mau Mau' movement. There are two aspects to the problem: one historiographical and the other historical. 'Mau Mau' has generated a huge literature, and it remains a contentious issue in both historical and popular thought. In spite of abundant controversy, however, much of the history remains obscure. We will thus start by surveying and analyzing the literature before engaging in individual research on select historical topics. Requirements: Students will be expected to write two major papers during the course of the seminar: the first a critical review of the literature on one of the topics listed for weeks 2-9, and the second a research paper on a select aspect of the overall topic. In each case, students should distribute copies oftheir paper to the other seminar participants (with two copies to me) by Tuesday noon preceding the relevant class. Research papers will first be presented in class and then revised for final submission at the end of the semester. Students will also be expected to write and present a critique of one of their colleagues' research papers during weeks 12-14. Readings: All required reading is available on reserve at H. C. White. The following are also available at the University Bookstore if you wish to buy them: Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Matigari W. -

Contributors

CONTRIBUTORS ANTS AAVER (1953). Education: 1972–1978 University of Tartu, Diploma of higher education equal to MA in English Language and Literature. Professional career: 1978–1994 University of Tartu, lecturer and senior lecturer of English at the Departments of Foreign Languages. From 1994 instructor of aviation English and vice rector for studies at the Tartu Aviation College (since 2008 the Estonian Aviation Academy). M.A. MARGUS ABEL (1967). Education: 2007–2010 Tallinn Pedagogical College, Youth Work specialization studies (professional higher education); 2010–2013 Tallinn University, Master’s studies and Master of Arts in educational sciences at the Institute of Educational Sciences. Professional career: Starting from 2010 assistant (lecturer) of youth work specialization at the Tallinn University Pedagogical College. Dr. PAUL BEAUDOIN (1960). Education: 1983 University of Miami in Coral Gables (Bachelor of Music.); 1987 New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, M.A. (Master of Music); 2002 Brandeis University, Ph.D. in Music Theory and Composition. Professional career: Dr. Beaudoin has taught music theory, music history, music composition and clarinet at Norteastern University, the New England Conservatory of Music, and online courses in music history and jazz at Somerset Community College. He is currently Assistant Professor of Humanities at Fitchburg State University, and a lecturer at Rhode Island College in Providence. For 2015, Dr. Beaudoin is a Fulbright Scholar for the music department at Tallinn University, in Tallinn, Estonia. MAIA BOLTOVSKY (1972). Education: 1990–1995 Tallinn Teacher Training University (since 2005 University of Tallinn), diploma of higher education equal to MA in teacher of English and German. Professional career: 1996–1998 EDF Officer Course, senior teacher of English; since 2000 to present ENDC, English teacher. -

Finnish Defence Forces International Centre the Many Faces of Military

Finnish Defence Forces International Finnish Defence Forces Centre 2 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Edited by Mikaeli Langinvainio Finnish Defence Forces FINCENT Publication Series International Centre 1:2011 1 FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FINCENT PUBLICATION SERIES 1:2011 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field EDITED BY MIKAELI LANGINVAINIO FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE TUUSULA 2011 2 Mikaeli Langinvainio (ed.): The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Finnish Defence Forces International Centre FINCENT Publication Series 1:2011 Cover design: Harri Larinen Layout: Heidi Paananen/TKKK Copyright: Puolustusvoimat, Puolustusvoimien Kansainvälinen Keskus ISBN 978–951–25–2257–6 ISBN 978–951–25–2258–3 (PDF) ISSN 1797–8629 Printed in Finland Juvenens Print Oy Tampere 2011 3 Contents Jukka Tuononen Preface .............................................................................................5 Mikaeli Langinvainio Introduction .....................................................................................8 Mikko Laakkonen Military Crisis Management in the Next Decade (2020–2030) ..............................................................12 Antti Häikiö New Military and Civilian Training - What can they learn from each other? What should they learn together? And what must both learn? .....................................................................................20 Petteri Kurkinen Concept for the PfP Training