The Erno Television Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1262 Nd Meeting

Information documents SG-AS (2016) 06 4 July 2016 ———————————————— Communication by the Secretary General of the Parliamentary Assembly to the 1262nd meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies1 (6 July 2016) ———————————————— 1 This document covers past activities of the Assembly since the meeting of the Bureau on 24 June 2016 (Strasbourg) and future activities up to the meeting of the Bureau on 5 September 2016 in Paris. I. Third part-session of 2016 (20-24 June 2016) A. Personalities 1. The following personalities addressed the Assembly (in chronological order): - Mr Thorbjørn JAGLAND, Secretary General of the Council of Europe - Mr Ioannis MOUZALAS, Alternate Minister for Migration Policy of Greece - Ms Marina KALJURAND, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Estonia, Chairperson of the Committee of Ministers - Ms Maud de BOER-BUQUICCHIO, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography - Mr Taavi RÕIVAS, Prime Minister of Estonia - Mr Alexis TSIPRAS, Prime Minister of Greece 2. Their speeches can be found on the web site of the Assembly: http://assembly.coe.int. B. Current affairs debate 3. The Assembly held a current affairs debate on “Reaffirming the role of the Assembly as a pan- European forum for inter-parliamentary dialogue and co-operation”, introduced by Mr Axel Fischer (Germany, EPP/CD). 4. On the basis of a proposal by the Presidential Committee, the Bureau adopted a declaration on Reaffirming the role of the Assembly as a pan-European forum for inter-parliamentary dialogue and co- operation (Appendix 1). C. Election of a judge to the European Court of Human Rights 5. -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ENTERTAIN. INFORM. ENGAGE. KEY FIGURES SHARE PERFORMANCE 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019 +31.15 % MDAX +16.41 % SXMP –5.82 % RTL GROUP INDEX = 100 –10.55 % PROSIEBENSAT1 RTL Group share price development for January to December 2019 based on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (Xetra) against MDAX, Euro Stoxx 600 Media (SXMP) and ProSiebenSat1 Fremantle’s America’s Got Talent: The Champions is a prime-time hit on NBC. 2 RTL Group Annual Report 2019 Key figures REVENUE 2015 – 2019 (€ million) EBITA 2015 – 2019 (€ million) 19 6,651 19 1,139 18 6,505 18 1,171 17 6,373 17 1,248 16 6,237 16 1,205 15 6,029 15 1,167 PROFIT FOR THE YEAR 2015 – 2019 (€ million) EQUITY 2015 – 2019 (€ million) 19 864 19 3,825 18 785 18 3,553 17 837 17 3,432 16 816 16 3,552 15 863 15 3,409 MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2015 – 2019 (€ billion) TOTAL DIVIDEND / DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2015 – 2019 (€)(%) 19 6.8 19 NIL* – 18 7.2 18 4.00** 6.3 17 10.4 17 4.00*** 5.9 16 10.7 16 4.00**** 5.4 15 11.9 15 4.00***** 4.9 *As of 31 December * On 2 April 2020, RTL Group’s Board of Directors decided to withdraw its earlier proposal of a € 4.00 per share dividend in respect of the fiscal year 2019, due to the coronavirus outbreak. No dividend will now be proposed to the Annual Meeting of Shareholders on 30 June 2020. -

Cejoc Fall 2013.Indb

ORIGINAL ARTICLE The worlds of “the others”? Czech television’s agenda of world news coverage Tomáš Trampota CHARLES UNIVERSITY IN PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC Kateřina Kučerová CHARLES UNIVERSITY IN PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC ABSTRACT: World news coverage is an important source of information about the worlds of “the others” for television audiences. Its production is connected with the hidden logic in the selection of issues, geographical areas, and actors. International news fl ows are infl uenced by news values, cultural and geographical contexts, and historical backgrounds. Th is article presents a study of foreign aff airs coverage in Czech television news programs based on a quantitative content analysis. It deals with questions such as: which countries or continents are included in the television news agendas? What is the frequency of their coverage? How is the news fl ow aff ected by the news values? KEYWORDS: world news coverage, television news coverage, agenda INTRODUCTION News coverage, with its manifested function to inform, belongs to the type of media content, which the study of mass communication, from the start of its institutional- ized form in most Western democracies with the fi rst half of the 20th century, is intensively looked into. Th e research of news production was gradually broadened from research for the foundation of sociology of news coverage1 introduced in the 1950s in the USA, aft er an in-depth research of news report content. News content research presents a range from the simple quantifi cation of topical agenda coming later (particularly aft er the turning point of the 1960s and 1970s) from the logic that the media agenda infl uences which topics circulating will be important to the public, aft er qualitative analysis of the representation of various social groups, in- cluding minorities, social eff ects up till aft er the case study of the representation of concrete events in news coverage. -

Annual Report 2015 Entertain. Inform. Engage

Annual Report 2015 Entertain. Inform. Engage. Key fi gures SHARE PRICE PERFORMANCE 30/04/2013 – 31/12/2015* + 42.7 % )RTL GROUP + 54.5 % MDAX + 48.1 % DJ STOXX 600 INDEX = 100 * RTL Group shares have been listed in the Prime Standard of the Frankfurt Stock Exchange since 30 April 2013. RTL GROUP REVENUE SPLIT In 2015, TV advertising accounted for 49.4 per cent of RTL Group’s total revenue, making the Group one of the most diversified groups when it comes to revenue. Content represented 22 per cent of the total, while greater exposure to fast-growing digital revenue streams and higher margin platform revenue will further improve the mix. 11.8 % OTHER 8.4 % DIGITAL 49.4 % TV ADVERTISING 22.0 % CONTENT 4.1 % PLATFORM REVENUE 4.3 % RADIO ADVERTISING Key fi gures REVENUE 2011 – 2015 (€ million) EBITA 2011 – 2015 (€ million) 15 6,029 15 1,167 14 5,808 14 1,144* 13 5,824* 13 1,148** 12 5,998 12 1,078 11 5,765 11 1,134 * Restated for IFRS 11 * Restated for changes in purchase price allocation ** Restated for IFRS 11 NET PROFIT ATTRIBUTABLE TO RTL GROUP SHAREHOLDERS 2011 – 2015 (€ million) EQUITY 2011 – 2015 (€ million) 15 789 15 3,409 14 652* 14 3,275* 13 870 13 3,593 12 597 12 4,858 11 696 11 5,093 * Restated for changes in purchase price allocation * Restated for changes in purchase price allocation TOTAL DIVIDEND/ MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2011 – 2015 (€ billion) DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2011 – 2015 (€ )(%) 15 11.9 15 4.00* 4.9 14 12.2 14 5.50** 6.8 13 14.4 13 7.00*** 10.0 12 11.7 12 10.50 13.9 11 11.9 11 5.10 6.6 * As of 31 December * Including -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ENTERTAIN. INFORM. ENGAGE. KEY FIGURES SHARE PERFORMANCE 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019 +31.15 % MDAX +16.41 % SXMP –5.82 % RTL GROUP INDEX = 100 –10.55 % PROSIEBENSAT1 RTL Group share price development for January to December 2019 based on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (Xetra) against MDAX, Euro Stoxx 600 Media (SXMP) and ProSiebenSat1 Fremantle’s America’s Got Talent: The Champions is a prime-time hit on NBC. 2 RTL Group Annual Report 2019 Key figures REVENUE 2015 – 2019 (€ million) EBITA 2015 – 2019 (€ million) 19 6,651 19 1,139 18 6,505 18 1,171 17 6,373 17 1,248 16 6,237 16 1,205 15 6,029 15 1,167 PROFIT FOR THE YEAR 2015 – 2019 (€ million) EQUITY 2015 – 2019 (€ million) 19 864 19 3,825 18 785 18 3,553 17 837 17 3,432 16 816 16 3,552 15 863 15 3,409 MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2015 – 2019 (€ billion) TOTAL DIVIDEND / DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2015 – 2019 (€) (%) 19 6.8 19 NIL* – 18 7.2 18 4.00** 6.3 17 10.4 17 4.00*** 5.9 16 10.7 16 4.00**** 5.4 15 11.9 15 4.00*****4.9 *As of 31 December * On 2 April 2020, RTL Group’s Board of Directors decided to withdraw its earlier proposal of a € 4.00 per share dividend in respect of the fiscal year 2019, due to the coronavirus outbreak. No dividend will now be proposed to the Annual Meeting of Shareholders on 30 June 2020. -

2020 Financial Statements for Bertelsmann SE & Co. Kgaa

Financial Statements and Combined Management Report Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA, Gütersloh December 31, 2020 Contents Balance sheet Income statement Notes to the financial statements Combined Management Report Responsibility Statement Auditor’s report 1 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Assets as of December 31, 2020 in € millions Notes 12/31/2020 12/31/2019 Non-current assets Intangible assets Acquired industrial property rights and similar rights as well as licenses to such rights 1 9 8 9 8 Tangible assets Land, rights equivalent to land and buildings 1 306 311 Technical equipment and machinery 1 1 1 Other equipment, fixtures, furniture and office equipment 1 42 47 Advance payments and construction in progress 1 7 2 356 361 Financial assets Investments in affiliated companies 1 15,974 14,960 Loans to affiliated companies 1 230 712 Investments 1 - - Non-current securities 1 1,461 1,252 17,665 16,924 18,030 17,293 Current assets Receivables and other assets Accounts receivable from affiliated companies 2 4,893 4,392 Other assets 2 94 148 4,987 4,540 Securities Other securities - - Cash on hand and bank balances 3 2,476 513 7,463 5,053 Prepaid expenses and deferred charges 4 20 20 25,513 22,366 2 Equity and liabilities as of December 31, 2020 in € millions Notes 12/31/2020 12/31/2019 Equity Subscribed capital 5 1,000 1,000 Capital reserve 2,600 2,600 Retained earnings Legal reserve 100 100 Other retained earnings 6 5,685 5,485 5,785 5,585 Net retained profits 898 663 10,283 9,848 Provisions Provisions for pensions and similar obligations 7 377 357 Provision -

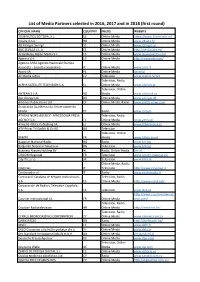

List of Media Partners Selected in 2016, 2017 and in 2018 (First Round)

List of Media Partners selected in 2016, 2017 and in 2018 (first round) OFFICIAL NAME COUNTRY FIELDS WEBSITE 20 MINUTOS EDITORA, S.L. ES Online Media https://www.20minutos.es/ 24sata d.o.o. HR Online Media www.24sata.hr AB Altinget Sverige SE Online Media www.altinget.se ABC SEVILLA S.L.U. ES Online Media http://sevilla.abc.es/ Actividades Digital Media S.L ES Online Media www.lavanguardia.com Agencia EFE ES Online Media http://www.efe.com/ Agenzia ANSA Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata - Società cooperativa IT Online Media www.ansa.it Agora SA PL Online Media agora.pl All Media Latvia LV Television www.skaties.lv/tv3 Television, Radio, ALPHA SATELLITE TELEVISION S.A. EL Online Media www.alphatv.gr Television, Online ANTENA 3 S.A. RO Media www.antena3.ro Aps Altinget.dk DK Online Media www.altinget.dk Arktinos Publications Ltd CY Online Media, Radio www.politis-news.com Associação Académica da Universidade do Minho PT Radio www.rum.pt ATHENS NEWS AGENCY - MACEDONIA PRESS Television, Radio, AGENCY S.A. EL Online Media www.amna.gr ATHENS VOICE Publishing SA EL Online Media www.athensvoice.gr ATV Privat TV GmbH & Co KG AU Television Television, Online BFMTV FR Media www.bfmtv.com/ Bugarian National Radio BG Radio www.bnr.bg Bulgarian National Television BG Television www.bnt.bg Business Nieuws Holding BV NL Radio, Online Media bnr.nl CIRCOM Regional FR Television www.circom-regional.eu City TV, s.r.o. SK Television www.tvba.sk Online Media, Radio, Citynews IT Television http://www.citynews.it Controradio srl IT Radio www.controradio.it Corporació Catalana de Mitjans Audiovisuals, Television, Radio, S.A. -

2013 Informe De Gestión Desempeño General De Los Canales Total Día Participación De Audiencias (Share% Personas) Meses – Franja Total Días 06:00 a 30:00 (L-D)

2013 Informe de Gestión Desempeño general de los canales Total Día Participación de Audiencias (Share% personas) Meses – Franja total días 06:00 a 30:00 (L-D) 30 25.4 25.5 23.9 24.6 25 23.5 23.4 21.9 20 21.7 21.2 20.4 20.9 19.6 15 Share % 10 4.9 4.9 4.5 4.6 4.8 4.6 5 0 ene-13 feb-13 mar-13 abr-13 may-13 jun-13 Canal UNO Institucional Canal Caracol Canal RCN Regionales Fuente datos: Ibope Colombia Markdata Media Workstation SHARE% / Total Colombia / Total día 06:00 a 30:00 / Lunes a Domingo 30 25.0 25.0 25.5 25.5 25 23.3 23.3 20 20.8 20.3 19.9 19.9 19.1 17.9 15 Share % 10 5.7 5.1 4.7 4.8 4.6 4.6 5 0 jul-13 ago-13 sep-13 oct-13 nov-13 dic-13 Canal UNO Institucional Canal Caracol Canal RCN Regionales TD LMMJVSD 6 / Informe de Gestión 2013 Tabla de Contenido 1 Junta Directiva 9 2 Carta del presidente 13 3 Informe de gestión 17 4 Dictamen del revisor fiscal 55 5 Estados financieros 59 6 Notas a los estados financieros 69 Certificación a los estados 109 7 financieros Proyecto de distribución 113 8 de utilidades 9 Informe del revisor fiscal 115 10 Estados financieros consolidados 119 Notas de los estados financieros 129 11 consolidados 1Junta Directiva Junta Directiva JUNTA DIRECTIVA PRINCIPALES Alejandro Santo Domingo Dávila Carlos Alejandro Pérez Dávila Alberto Preciado Arbeláez Alberto Lleras Puga Carlos Arturo Londoño Gutiérrez Alvaro Villegas Villegas Gonzalo Córdoba Mallarino REVISOR FISCAL KPMG Ltda. -

Sourcebook with Marie's Help

AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009-10 EDITION WELCOME | SOURCEBOOK AIB Global WELCOME Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009 EDITION In the people-centric world of broadcasting, accurate information is one of the pillars that the industry is built on. Information on the information providers themselves – broadcasters as well as the myriad other delivery platforms – is to a certain extent available in the public domain. But it is disparate, not necessarily correct or complete, and the context is missing. The AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook fills this gap by providing an intelligent framework based on expert research. It is a tool that gets you quickly to what you are looking for. This media directory builds on the AIB's heritage of more than 16 years of close involvement in international broadcasting. As the global knowledge The Global Broadcasting MIDDLE EAST/AFRICA network on the international broadcasting Sourcebook is the Richie Ebrahim directory of T +971 4 391 4718 industry, the AIB has over the years international TV and M +971 50 849 0169 developed an extensive contacts database radio broadcasters, E [email protected] together with leading EUROPE and is regarded as a unique centre of cable, satellite, IPTV information on TV, radio and emerging and mobile operators, Emmanuel researched by AIB, the Archambeaud platforms. We are in constant contact -

Central European Media Enterprises Ltd

CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTERPRISES LTD FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 3/15/2001 For Period Ending 12/31/2000 C/O CME DEVELOPEMENT CORP 8TH FLOOR ALDWYCH HOUSE Address 71-91 ALDWYCH LONDON, WC2B 4HN Telephone 011442074305430 CIK 0000925645 Industry Broadcasting & Cable TV Sector Services Fiscal 12/31 Year SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10 -K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2000 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER: 0-24796 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTERPRISES LTD. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) BERMUDA NOT APPLICABLE (STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF INCORPORATION) (IRS EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NO.) CLARENDON HOUSE CHURCH STREET HAMILTON HM CX BERMUDA (ADDRESS OF PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) (441) 296-1431 (REGISTRANT'S TELEPHONE NUMBER) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: NONE SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: CLASS A COMMON STOCK, $0.08 PAR VALUE 9.375% NOTES DUE 2004 8.125% NOTES DUE 2004 Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for each shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. YES X NO Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant's knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

How Enex Is Transforming from Technical Service Into Content Provider

week 14 / 4 April 2013 “A TRULY GLOBAL NEWS PROVIDER” How Enex is transforming from technical service into content provider Luxembourg Germany United States The Netherlands Bertelsmann RTL Now app Married to Medicine RTL Nieuws wins to reduce its now offers kicks off well Tegel awards shareholding live TV feed in RTL Group week 14 / 4 April 2013 “A TRULY GLOBAL NEWS PROVIDER” How Enex is transforming from technical service into content provider Luxembourg Germany United States The Netherlands Berteslmann RTL Now app Married to Medicine RTL Nieuws wins to reduce its now offers kicks off well Tegel awards shareholding live TV feed in RTL Group Cover Montage with Vincent Regnier, Henning Tewes and Uwe Böhler in London (from left to right) Publisher RTL Group 45, Bd Pierre Frieden L-1543 Luxembourg Editor, Design, Production RTL Group Corporate Communications & Marketing k before y hin ou T p r in t backstage.rtlgroup.com backstage.rtlgroup.fr backstage.rtlgroup.de QUICK VIEW Bertelsmann confi rms its intention to reduce its shareholding in RTL Group by way of a secondary public offering RTL Group p. 7–8 “RTL anytime and anywhere, in a single app” RTL Interactive p. 9 Atlanta’s medical society FremantleMedia North America p. 10 The synergy vehicle for news Enex p. 4–6 The Voice Kids now on tour RTL 4 p. 11 RTL Nieuws wins two Tegel awards Big Picture RTL Nederland p.13 p. 12 SHORT NEWS PEOPLE p. 14 p.15 THE SYNERGY Backstage met with Henning Tewes, Uwe Böhler and Vincent Regnier at the VEHICLE FOR Enex Executive Committee meeting in London to talk about how Enex is transforming from technical NEWS service to content provider and becoming a global player in the news field. -

Directors' Report

DIRECTORS’ REPORT, CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND AUDIT REPORT 52 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 56 Corporate profile 68 Financial review 74 Capital markets and share 79 General management statement on the fiscal year 2017 performance 80 Review by segments 101 Non-financial information 118 Outlook 119 MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY STATEMENT 120 CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENT 121 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 122 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 123 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 124 CONSOLIDATED CASH FLOW STATEMENT 125 NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 125 Significant accounting policies 139 Accounting estimates and judgements 141 Key performance indicators 144 Financial risk management 156 Segment reporting 160 Acquisitions and disposals 170 Details on consolidated income statement 175 Details on consolidated statement of financial position 204 Commitments and contingencies 205 Related parties 208 Subsequent events 209 Group undertakings 215 AUDIT REPORT 221 GLOSSARY 226 CREDITS 227 FIVE-YEAR SUMMARY RTL Group Annual Report 2017 51 Directors’ report GERMAN TV BUSINESS DRIVES RTL GROUP’S RECORD RESULTS IN 2017 Full-year revenue up 2.2 per cent to € 6,373 million; EBITDA up 3.8 per cent to € 1,464 million Digital revenue1 continues to grow dynamically, up by 23.3 per cent to € 826 million Attractive shareholder returns: final dividend of € 3.00 per share in addition to the interim dividend of € 1.00 per share already paid in September 2017, representing a dividend yield of 5.9 per cent for the