As a Fallible Narrator, Nelly Dean Alters the Course of the Story. Is She Completely Blameless in What Occurs?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Wuthering Heights (William Wyler, 1939; Robert Fuest, 1970; Jacques

1 Wuthering Heights (William Wyler, 1939; Robert Fuest, 1970; Jacques Rivette, 1985; Peter Kosminsky, 1992) Wyler’s ghastly sentimental version concedes nothing to the proletariat: with the exception of Leo G. Carroll, who discards his usual patrician demeanour and sports a convincing Yorkshire accent as Joseph, all the characters are as bourgeois as Sam Goldwyn could have wished. Not even Flora Robson as Ellen Dean – she should have known better – has the nerve to go vocally downmarket. Heathcliff may come from the streets of Liverpool, and may have been brought up in the dales, but Olivier’s moon-eyed Romeo-alternative version of him (now and again he looks slightly dishevelled, and slightly malicious) comes from RADA and nowhere else. Any thought that Heathcliff is diabolical, or that either he or Catherine come from a different dimension altogether was, it’s clear, too much for Hollywood to think about. Couple all this with Merle Oberon’s flat face, white makeup, too-straight nose and curtailed hairstyles, and you have a recipe for disaster. We’re alerted to something being wrong when, on the titles, the umlaut in Emily’s surname becomes an acute accent. Oberon announces that she “ is Heathcliff!” in some alarm, as if being Heathcliff is the last thing she’d want to be. When Heathcliff comes back, he can of course speak as high and mightily as one could wish – and does: and the returned Olivier has that puzzled way of looking straight through a person as if they weren’t there which was one of his trademarks (see left): for a moment the drama looks as if it might ratchet up a notch or two. -

Wuthering Heights

LEVEL 5 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Wuthering Heights Emily Brontë After old Mr Earnshaw’s death, Heathcliff is treated EASYSTARTS badly by Catherine’s brother, Hindley. Then, when he overhears Catherine say she will marry Edgar Linton, Heathcliff disappears, swearing to get his revenge on the two families. LEVEL 2 Three years later, now rich and respectable, Heathcliff sets about his destructive business. First, Hindley’s LEVEL 3 weakness for alcohol and gambling enables Heathcliff to gain control of the Earnshaw estate and Hindley’s son. Then, to her brother Edgar’s horror, he marries LEVEL 4 Isabella Linton. Catherine is also greatly upset by this; she becomes ill and dies after giving birth to her and Edgar’s daughter, a second Catherine, but not before Heathcliff About the author and she have sworn undying love for each other. Finally, LEVEL 5 Emily Brontë was born in 1818 into a clergyman’s family when Heathcliff’s own son comes to Wuthering Heights, of five girls and a boy. The family lived in Haworth, a Heathcliff sees how he can also acquire the Lintons’ moorland village in West Yorkshire, northern England. property. But revenge, after all, isn’t so sweet. Tortured LEVEL 6 Their mother died in 1821 and four of the sisters, by memories of Catherine, he is overcome by guilt and including Emily, aged 6, were sent away to a boarding madness. With his death, all ends happily. school, where conditions were so bad that two of them Chapters 1–4: Mr Lockwood is a new tenant at died. -

Des Hauts De Hurlevent À La Migration Des Coeurs : L'émergence D'une Identité Composite

Mémoire de Master Université de Limoges Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines Département d'études anglophones Littérature anglophone présenté et soutenu par Sultana NEZIRI le 22 septembre 2017 Des Hauts de Hurlevent à La Migration des Coeurs : l'émergence d'une identité composite Mémoire dirigé par Bertrand ROUBY Sultana NEZIRI | Mémoire de Master | Université de Limoges | 2017 2 Remerciements En premier lieu, j'aimerais remercier Bertrand Rouby, pour ses conseils en tant que directeur de recherche, mais surtout pour m'avoir permis de découvrir les œuvres de Jean Rhys et de Maryse Condé. Ces univers m'ont touchée par leur richesse et leurs spécificités, m'offrant la possibilité d'aborder des romans qui m'ont marquée, ceux des sœurs Brontë, sous un angle différent. Je remercie les amis dont le soutien m'a aidée, surtout au cours des dernières étapes: Mathilde, Anaïs, Marion et Louise. Merci à Garance d'avoir pris en charge un aspect qui est hors de ma portée : la mise en page de ce mémoire, ce qui me décharge d'un poids considérable. Enfin, avoir un frère qui soit en mesure de comprendre les petits maux et les grands tracas que peut engendrer la cécité au cours d'un processus de rédaction a été essentiel. Sultana NEZIRI | Mémoire de Master | Université de Limoges | 2017 3 Sultana NEZIRI | Mémoire de Master | Université de Limoges | 2017 4 Droits d'auteurs Cette création est mise à disposition selon le Contrat : « Attribution-Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale-Pas de modification 4.0 International » disponible en ligne : http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Sultana NEZIRI | Mémoire de Master | Université de Limoges | 2017 5 Sultana NEZIRI | Mémoire de Master | Université de Limoges | 2017 6 Table des matières Introduction......................................................................................................................................9 Partie I : Unité et fragmentation......................................................................................................13 I.1. -

Tools of Horror: Servants in Gothic Novel Jacob Herrmann South Dakota State University

The Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 9 Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume Article 8 9: 2011 2011 Tools of Horror: Servants in Gothic Novel Jacob Herrmann South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/jur Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Herrmann, Jacob (2011) "Tools of Horror: Servants in Gothic Novel," The Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 9 , Article 8. Available at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Division of Research and Economic Development at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GS019 JUR11_GS JUR text 1/19/12 1:22 PM Page 57 TOOLS OF HORROR: SERVANTS IN GOTHIC NOVEL 57 Tools of Horror: Servants in Gothic Novel Author: Jacob Herrmann Faculty Advisor: Dr. Barst Department: English TOOLS OF HORROR: SERVANTS IN GOTHIC NOVEL The servants within 18th- and 19th-century English literature play an undoubtedly vital role within everyday life. Elizabeth Langland highlights this point in her discussion of the middle class: “Running the middle-class household, which by definition included at least one servant, was an exercise in class management, a process both inscribed and revealed in the Victorian novel” (291). In Victorian England, especially, class and rank were everything. -

Dalbertisdarknature

Chapter 3 // UNPUBLISHED PAPER NOT FOR CITATION OR DISTRIBUTION Dark Nature: A Critical Return to Brontë Country Deirdre d’Albertis This is certainly a beautiful country! In all England, I do not believe that I could have fixed on a situation so completely removed from the stir of society. A perfect misanthropist’s heaven—and Mr. Heathcliff and I are such a suitable pair to divide the desolation between us!1 Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights So begins the tale of one of literature’s most self-regarding, critically obtuse narrators: Emily Brontë’s Lockwood invites readers of Wuthering Heights to share in his metropolitan traveler’s gaze as he familiarizes himself with Yorkshire and its inhabitants, strange and wild as they turn out to be. An outsider’s view of Brontë country as both “completely removed” and a “misanthropist’s heaven” has been reflected in critical commentary ever since the novel’s original publication in 1847. In her Editor’s Preface to the 1850 edition, Charlotte Brontë characterizes Wuthering Heights as “moorish, and 1 Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights (ed. Dunn), 3. Further references will be cited parenthetically. wild, and knotty as a root of heath.”2 The book, she suggests, shares aspects of the land that are hard to appreciate: what Lockwood refers to as “a beautiful country” would not have seemed so to many of his contemporaries.3 As Lucasta Miller points out, the now iconic landscape of the Yorkshire moors came into view only as reception of Brontë’s novel changed over time” (154). Elizabeth Gaskell opens her Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) on a similar note: it was this hostile, nonhuman terrain that shaped the imaginative resources shared by the three Brontë sisters. -

Chapter Two: Heathcliff Connection

Chapter Two: Heathcliff Connection We would never have heard about Richard Sutton being a possible role model for Heathcliff had it not been for Kim Lyon and, subsequently, academic Christopher Heywood.i We first learn about Richard Sutton being linked to Heathcliff in an article entitled ‘Real-life story behind “Wuthering Heights,”’ published in The Observer, 30th September 1984 written by Robert Low and David Boulton. They conclude, The real-life model for Heathcliff, one of the most enigmatic and fascinating characters in English fiction, may have been uncovered, thanks to the diligent research of an amateur historian. If Mrs Kim Lyon’s theory is correct, Emily Bronte’s stormy creation in ‘Wuthering Heights’ was based on one Richard Sutton (1782-1851) whose life in the Cumbrian village of Dent mirrors that of Heathcliff to an uncanny degree….‘ Before we look at what Lyon and Heywood have to say it is worth noting the ‘uncanny’ similarities between Wuthering Heights, and to a lesser degree, Jane Eyre, and the Richard Sutton story. Both Heathcliff and Richard Sutton are taken in by wealthy farmers. They become rich and eventually own the isolated farm house on the hill top as well as the manor house in the valley below; both chose to live in the farm house whilst renting out the manor house. Whilst dressing like gentlemen, their manner and speech made it clear they were not. 1 Heathcliff, Richard Sutton (and Jane Eyre) are orphans.ii All three come into money: we do not know where Heathcliff gets his money from whilst Jane inherits hers from her uncle John in Madeira and Richard Sutton inherits his from Ann Sill who had inherited her wealth from her uncle John in Jamaica. -

119-2014-04-09-Wuthering Heights.Pdf

1 CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XVI CHAPTER XVII CHAPTER XVIII CHAPTER XIX CHAPTER XX CHAPTER XXI CHAPTER XXII CHAPTER XXIII CHAPTER XXIV CHAPTER XXV CHAPTER XXVI CHAPTER XXVII CHAPTER XXVIII CHAPTER XXIX CHAPTER XXX CHAPTER XXXI Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte 2 CHAPTER XXXII CHAPTER XXXIII CHAPTER XXXIV Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte The Project Gutenberg Etext of Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte #2 in our series by the Bronte sisters [Anne and Charlotte, too] Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte December, 1996 [Etext #768] The Project Gutenberg Etext of Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte *****This file should be named wuthr10.txt or wuthr10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, wuthr11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, wuthr10a.txt. Scanned and proofed by David Price, email [email protected] We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. -

"Wuthering Heights" and "Shirley"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 Illness and Anger: Issues of Power in "Wuthering Heights" and "Shirley" Margaret Elise Jordan College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jordan, Margaret Elise, "Illness and Anger: Issues of Power in "Wuthering Heights" and "Shirley"" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625747. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-69d3-wb86 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ILLNESS AND ANGER: ISSUES OF POWER IN WUTHERING HEIGHTS AND SHIRLEY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Margaret Elise Jordan 1992 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, August 1992 Deborah Denenholz Morse Terry L. Meyers /$- ■ Christopher Bongie 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Deborah Denenholz Morse, under whose guidance this thesis was conducted, for her tireless and cheerful support. I am also indebted to Professors Terry L. Meyers and Christopher Bongie for their careful reading and criticism of the manuscript, and most especially for their willingness to read 79 pages at the last moment. -

Les Hauts De Hurle-Vent

Emily Brontë LLeess HHaauuttss ddee HHuurrllee--VVeenntt BeQ Emily Brontë LLeess HHaauuttss ddee HHuurrllee--VVeenntt (Wuthering Heights) Traduction de Frédéric Delebecque La Bibliothèque électronique du Québec Collection À tous les vents Volume 593 : version 1.0 2 Les Hauts de Hurle-Vent Édition de référence : Le Livre de Poche, no 105. Image de couverture : Caspar David Friedrich. 3 Avertissement du traducteur Le roman qu’on va lire occupe dans la littérature anglaise du XIXe siècle une place tout à fait à part. Ses personnages ne ressemblent en rien à ceux qui sortent de la boîte de poupées à laquelle, selon Stevenson, les auteurs anglais de l’ère victorienne, « muselés comme des chiens », étaient condamnés à emprunter les héros de leurs récits. Ce livre est l’œuvre d’une jeune fille qui n’avait pas encore atteint sa trentième année quand elle le composa et dont c’était, à l’exception de quelques pièces de vers, la première œuvre littéraire. Elle ne connaissait guère le monde, ayant toujours vécu au fond d’une province reculée et dans une réclusion presque absolue. Fille d’un pasteur irlandais et d’une mère anglaise qu’elle perdit en bas âge, sa courte vie s’écoula presque entière dans un village du Yorkshire, avec ses deux sœurs et un 4 frère, triste sire qui s’enivrait régulièrement tous les soirs. Les trois sœurs Brontë trouvèrent dans la littérature un adoucissement à la rigueur d’une existence toujours austère et souvent très pénible. Après avoir publié un recueil de vers en commun, sans grand succès, elles s’essayèrent au roman. -

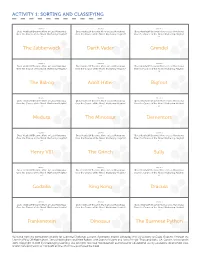

The Jabberwock Darth Vader Grendel the Balrog Adolf Hitler Bigfoot

ACTIVITY 1: SORTING AND CLASSIFYING LESSON 4 LESSON 4 LESSON 4 Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? 1-1 1-2 1-3 The Jabberwock Darth Vader Grendel LESSON 4 LESSON 4 LESSON 4 Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? 1-4 1-5 1-6 The Balrog Adolf Hitler Bigfoot LESSON 4 LESSON 4 LESSON 4 Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? 1-7 1-8 1-9 Medusa The Minotaur Dementors LESSON 4 LESSON 4 LESSON 4 Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? Over the Course of the Novel Wuthering Heights? 1-10 1-11 1-12 Henry VIII The Grinch Sully LESSON 4 LESSON 4 LESSON 4 Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous Does Heathcliff Become More or Less Monstrous -

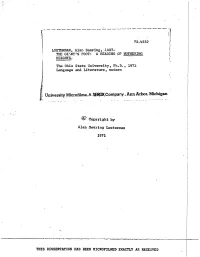

I, University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72-t*552 LOXTERMAN, Alan Searing, 1937- THE GIANT'S FOOT: A READING OF WUTHERING HEIGHTS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern I, University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan ® Copyright by Alan Searing Loxterman 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE GIANT' S FOOTs A READING OK WUTHERING HEIGHTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University! ! By Alan Searing Loxterman, A.B., H,A, i * * * * w i The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by AdJviser * Department of English PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have indistinct p rin t. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS ” • . there [Wutherlncj Heights! stands colossal, dark, and frowning, half statue, half rocks in the former sense, terrible and goblin-like; in the latter, almost beautiful, for its colouring is of mellow grey, and moorland moss clothes it; and heath, with its blooming bells and balmy fragrance, grows faithfully close to the giant's foot," CHARLOTTE BRONTE Editor's Preface To the New Edition (1850) of Wutherinq Heights ii In fond dedication to ray wife and ray parents for their support and encouragement iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My greatest debt is to my adviser. Professor Arnold Shapiro. His critical instincts were so unerring that, from him, praise was doubly welcome. I would also like to thank Professors Daniel R. Barnes, Ford T. Swetnam, Jr., and Charles W. Hoffmann for their valuable comments and useful suggestions for improvement. iv VITA May 21, 1937 • • ■ Born-Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1959 «••••• • A, B. -

Les Hauts De Hurlevent

Fiche pédagogique Les Hauts de Hurlevent Sortie en salles 9 janvier 2013 (Suisse romande) 5 décembre 2012 (France) Titre original : Wuthering Heights et Hindley, son fils majeur, Résumé devient le propriétaire du Film long métrage, Royaume- ème Uni, 2012 Une nuit, à la fin du 18 siècle, domaine de Hurlevent. Il oblige dans la campagne britannique, Heathcliff à prendre une Réalisation et scénario : Mr. Earnshaw, père de famille décision : soit il part, soit il Andrea Arnold catholique, ramène chez lui un devient son esclave. Heathcliff jeune orphelin noir, lui offrant reste, en vivant dans l'écurie Interprètes : accueil et éducation. avec les animaux, dans le seul Kaya Scodelario, James espoir de pouvoir un jour Howson, Solomon Glave, Ses enfants, Hindley et conquérir Catherine. Shannon Beer, Steve Evets Catherine, ne réagissent pas Mais Catherine laisse peu à très bien. Ils ont l’impression Distribution en Suisse: que le jeune orphelin, baptisé peu Heathcliff à la merci de Frenetic films AG Heathcliff, reçoit toute l’attention son frère, se mariant avec le du père qui se bat pour son voisin Edgar Linton, raffiné et Version originale anglaise, intégration dans la famille de belles manières. Heathcliff sous-titrée français « comme un frère ». Hindley le quitte Hurlevent sous la pluie. bat violemment, Catherine Durée : 2h08 change d’attitude et en a pitié. Quelques années plus tard, il y retourne, incapable de faire le Elle s'efforce de le protéger. Public concerné : Heathcliff s'efforce d'instaurer deuil de son grand amour de âge légal : 16 ans une relation d’affection et de jeunesse. Il veut reconquérir âge suggéré : 16 ans complicité avec Catherine mais Catherine, et se venger de leurs jours heureux durent peu Hindley… Décision de la commission de temps.