Goliath Grouper Letter to Commissioners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mississippi River Find

The Journal of Diving History, Volume 23, Issue 1 (Number 82), 2015 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 04/10/2021 06:15:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32902 First Quarter 2015 • Volume 23 • Number 82 • 23 Quarter 2015 • Volume First Diving History The Journal of The Mississippi River Find Find River Mississippi The The Journal of Diving History First Quarter 2015, Volume 23, Number 82 THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER FIND This issue is dedicated to the memory of HDS Advisory Board member Lotte Hass 1928 - 2015 HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION PO BOX 2837, SANTA MARIA, CA 93457 USA TEL. 805-934-1660 FAX 805-934-3855 e-mail: [email protected] or on the web at www.hds.org PATRONS OF THE SOCIETY HDS USA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ernie Brooks II Carl Roessler Dan Orr, Chairman James Forte, Director Leslie Leaney Lee Selisky Sid Macken, President Janice Raber, Director Bev Morgan Greg Platt, Treasurer Ryan Spence, Director Steve Struble, Secretary Ed Uditis, Director ADVISORY BOARD Dan Vasey, Director Bob Barth Jack Lavanchy Dr. George Bass Clement Lee Tim Beaver Dick Long WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONTINUED Dr. Peter B. Bennett Krov Menuhin SUPPORT OF THE FOLLOWING: Dick Bonin Daniel Mercier FOUNDING CORPORATIONS Ernest H. Brooks II Joseph MacInnis, M.D. Texas, Inc. Jim Caldwell J. Thomas Millington, M.D. Best Publishing Mid Atlantic Dive & Swim Svcs James Cameron Bev Morgan DESCO Midwest Scuba Jean-Michel Cousteau Phil Newsum Kirby Morgan Diving Systems NJScuba.net David Doubilet Phil Nuytten Dr. -

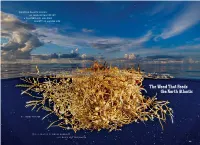

The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic

DRIFTING PLANTS KNOWN AS SARGASSUM SUPPORT A COMPLEX AND AMAZING VARIETY OF MARINE LIFE. The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic BY JAMES PROSEK PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID DOUBILET AND DAVID LIITTSCHWAGER 129 Hatchling sea turtles, like this juvenile log- gerhead, make their way from the sandy beaches where they were born toward mats of sargassum weed, finding food and refuge from predators during their first years of life. PREVIOUS PHOTO A clump of sargassum weed the size of a soccer ball drifts near Bermuda in the slow swirl of the Sargasso Sea, part of the North Atlantic gyre. A weed mass this small may shelter thousands of organisms, from larval fish to seahorses. DAVID DOUBILET (BOTH) 130 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC THE WEED THAT FEEDS THE NORTH ATLANTIC 131 ‘There’s nothing like it in any other ocean,’ says marine biologist Brian Lapointe. ‘There’s nowhere else on our blue planet that supports such diversity in the middle of the ocean—and it’s because of the weed.’ LAPOINTE IS TALKING about a floating seaweed known as sargassum in a region of the Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea. The boundaries of this sea are vague, defined not by landmasses but by five major currents that swirl in a clockwise embrace around Bermuda. Far from any main- land, its waters are nutrient poor and therefore exceptionally clear and stunningly blue. The Sargasso Sea, part of the vast whirlpool known as the North Atlantic gyre, often has been described as an oceanic desert—and it would appear to be, if it weren’t for the floating mats of sargassum. -

Phaidon Rights Catalogue/LBF 2021 Phaidon Rights Catalogue/LBF 2021

Phaidon Rights Catalogue/LBF 2021 Phaidon Rights Catalogue/LBF 2021 phaidon.com African Artists From 1882 to Now Phaidon Editors A groundbreaking A-to-Z appraisal of the work of 300 modern and contemporary artists born or based in Africa. In recent years Africa’s booming art scene has Created in collaboration with global experts, to ensure 290 x 250 mm ‘Collectors the world over are buying ‘Things are changing. The visibility of ‘Africa’s contemporary art scene is gained substantial global attention, with a growing engaging, accessible, and culturally sensitive texts 9 7/8 x 11 3/8 inches modern and contemporary art from art and artists from Africa is improving.’ characterized by a dynamic list of number of international exhibitions and a stronger- - 336 pp Africa [which]… has become one of the – Frieze Magazine exceptional artists whose aesthetic 300 col illus. than-ever presence on the art market worldwide. Part of the popular The Art Book family, A-Z books hottest art markets.’ – Economist innovation and conceptual profundity Here, for the first time, is the most substantial that document the work of the most important creators Hardback ‘Modern and contemporary African art has paved the way for the next ISBN: 978-1-83866-243-1 survey to date of modern and contemporary - 978 1 83866 243 1 ‘The meteoric rise of African art: the art began to enter the mainstream nearly generation.’ – The Culture Trip African-born or Africa-based artists. Working with Broad appeal for general art lovers, and an essential world has at last woken up to the power 10 years ago and … has maintained a panel of experts, this volume builds on the reference book for curators, gallerists, collectors, of African artists.’ – Evening Standard market momentum.’ – Financial Times ‘If you aren’t familiar with Africa’s success of Phaidon’s bestselling Great Women artists, and all students of arts and of African studies leading artistic forces, you best take Artists in re-writing a more inclusive and diverse £ 49.95 UK note.’ – The Huffington Post $ 69.95 US version of art history. -

Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society ®

our world-underwater scholarship society ® 47th Annual Awards Program – June 3 - 5, 2021 Welcome to the 47th anniversary celebration of the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society®. It has always been a great pleasure for me as president of the Society to bring the “family” together each year in New York City, so of course it is with great disappointment that for the second year we are unable to do so. A year ago, as the pandemic was beginning to spread throughout the world, the board of directors made the difficult decision to put all scholarship and internship activities on hold. 2020 was the first time in the Society’s history that we did not put Scholars or Interns in the field. But there is good news – the Society has new energy and is working with our hosts and sponsors to safely get our incoming 2021 Scholars and Interns started on their journeys. We bring three new Rolex Scholars and five new interns into our family for a total of 103 Rolex Scholars and 107 interns since the inception of the Society, and all of this has been accomplished by our all-volunteer organization. Forty-seven years of volunteers have been selfless in their efforts serving as directors, officers, committee members, coordinators, and technical advisors all motivated to support the Society’s mission “to promote educational activities associated with the underwater world.” None of this would have been possible without the incredible support by the Society’s many organizational partners and corporate sponsors throughout the years. The one constant in the Society’s evolution has been Rolex which continues to support the Society as part of its Perpetual Planet Initiative. -

2007 Dema Reaching out Award Nomination Form

2013 DEMA REACHING OUT AWARD NOMINATION FORM ABOUT THE AWARD: The Reaching Out Award was first presented in 1989. The original intent was to recognize individuals who have made a significant contribution to the sport of diving by “reaching out” in some special way to improve the sport for everyone. There are many ways to reach out and do something extraordinary for the sport. Most that have been recognized were pioneers who helped develop techniques related to their special areas of expertise. Their contributions have been made in such areas as photography, training, equipment design, publishing, travel, retailing, water safety, exploration and science. Since its inception, the Reaching Out Award has become more than just recognition of these individual achievements; it has become the industry’s HALL OF FAME. These are the leaders and heroes of our sport. They are the ones who have helped make diving what it is today. Some have greater name recognition than others, but each is, in their own way, as important to the development of diving as any other. To become a member of DEMA’s Hall Of Fame is an extraordinary achievement and is available only to those who truly deserve to be recognized for their outstanding efforts and contribution to the sport. There are many individuals whose works go unnoticed and unheralded. The form below is an opportunity for anyone in the industry to make an application either for themselves or for someone whom they believe honestly deserves to be so recognized. CRITERIA: There are only two criteria for an applicant to the DEMA Hall of Fame and recipient of the Reaching Out Award: 1. -

TPG Exhibition List

Exhibition History 1971 - present The following list is a record of exhibitions held at The Photographers' Gallery, London since its opening in January 1971. Exhibitions and a selection of other activities and events organised by the Print Sales, the Education Department and the Digital Programme (including the Media Wall) are listed. Please note: The archive collection is continually being catalogued and new material is discovered. This list will be updated intermittently to reflect this. It is for this reason that some exhibitions have more detail than others. Exhibitions listed as archival may contain uncredited worKs and artists. With this in mind, please be aware of the following when using the list for research purposes: – Foyer exhibitions were usually mounted last minute, and therefore there are no complete records of these brief exhibitions, where records exist they have been included in this list – The Bookstall Gallery was a small space in the bookshop, it went on to become the Print Room, and is also listed as Print Room Sales – VideoSpin was a brief series of worKs by video artists exhibited in the bookshop beginning in December 1999 – Gaps in exhibitions coincide with building and development worKs – Where beginning and end dates are the same, the exact dates have yet to be confirmed as the information is not currently available For complete accuracy, information should be verified against primary source documents in the Archive at the Photographers' Gallery. For more information, please contact the Archive at [email protected] -

The Bahamas and Florida Keys

THE MAGAZINE OF DIVERS ALERT NETWORK FALL 2014 A TASTE OF THE TROPICS – THE BAHAMAS AND FLORIDA KEYS THE UNDERWATER WILD OF CRISTIAN DIMITRIUS CULTURE OF DIVE SAFETY PROPELLER HAZARDS Alert_DS161.qxp_OG 8/29/14 11:44 AM Page 1 DS161 Lithium The Choice of Professionals Only a round flash tube and custom made powder-coated reflector can produce the even coverage and superior quality of light that professionals love. The first underwater strobe with a built-in LED video light and Lithium Ion battery technology, Ikelite's DS161 provides over 450 flashes per charge, instantaneous recycling, and neutral buoyancy for superior handling. The DS161 is a perfect match for any housing, any camera, anywhere there's water. Find an Authorized Ikelite Dealer at ikelite.com. alert ad layout.indd 1 9/4/14 8:29 AM THE MAGAZINE OF DIVERS ALERT NETWORK FALL 2014 Publisher Stephen Frink VISION Editorial Director Brian Harper Striving to make every dive accident- and Managing Editor Diana Palmer injury-free. DAN‘s vision is to be the most recognized and trusted organization worldwide Director of Manufacturing and Design Barry Berg in the fields of diver safety and emergency Art Director Kenny Boyer services, health, research and education by Art Associate Renee Rounds its members, instructors, supporters and the Graphic Designers Rick Melvin, Diana Palmer recreational diving community at large. Editor, AlertDiver.com Maureen Robbs Editorial Assistant Nicole Berland DAN Executive Team William M. Ziefle, President and CEO Panchabi Vaithiyanathan, COO and CIO DAN Department Managers Finance: Tammy Siegner MISSION Insurance: Robin Doles DAN helps divers in need of medical Marketing: Rachelle Deal emergency assistance and promotes dive Medical Services: Dan Nord safety through research, education, products Member Services: Jeff Johnson and services. -

Neaqar05.Pdf

((New England Aquarium)) Annual Report 2005 ((Letter to our Supporters )) Dear Friends of the New England Aquarium: In 2005, change was all around us at the New England Aquarium. One of us, Bud, took the helm as the Aquarium’s new President and CEO in September, ready and eager to lead the Aquarium forward. We welcomed three new trustees and eleven new overseers to our two boards, adding a great deal of experience and passion for the Aquarium’s mission to present, promote and protect the world of water. Down on Central Wharf, we introduced a terrific series of theme programs (Sharks: Tales and Truths and Turtle Trek) to give visitors a whole new way to experience our exhibits. We made significant progress in modernizing key structural components of the Aquarium, saw attendance increase three percent over 2004, and continued to strengthen our finances by finishing the year with an operating surplus. We also watched the Boston waterfront take on new life as the Rose Kennedy Greenway finally began to rise from the dust and clutter of the Big Dig. Equally important, we extended the reach of our pioneering marine conservation programs, continued our longstanding efforts to protect the North Atlantic right whale, Kemp’s ridley seaturtle and other endangered species, and forged exciting part- nerships with businesses to provide consumers with seafood harvested from well-managed stocks throughout the world. All of these developments give us great confi- dence in the Aquarium’s future, and have helped lay the groundwork for a new five-year Action Plan that will be completed by the end of 2006. -

English Reading Answer Booklet

En English tests KEY STAGE 2 LEVELS 3–5 English reading answer booklet First name Middle name Last name Date of birth Day Month Year School name DfE number These sample materials have been provided for illustrative purposes, as an indication of what future key stage 2 English reading tests that are not ‘themed’ will look like. They are not intended to be used as a practice test. The reading booklet, reading answer booklet and mark scheme have not been through the same rigorous test development process that a live test would go through. The materials have not been trialled in schools. SAMPLE [BLANK PAGE] Please do not write on this page. 02 Instructions Questions and answers You have one hour to complete this test. Read one text and answer the questions about that text before moving on to read the next text. In this booklet, there are different types of question for you to answer in different ways. The space for your answer shows you what type of writing is needed. • short answers Some questions are followed by a short line or box. This shows that you need only write a word or phrase in your answer. • several line answers Some questions are followed by a few lines. This gives you space to write more words or a sentence or two. • longer answers Some questions are followed by a large box. This shows that a longer, more detailed answer is needed to explain your opinion. You can write in full sentences if you want to. • other answers For some questions you do not need to write anything at all and you should tick, draw lines to, or put a ring around your answer. -

The Return of the Lama

Historical Diver, Volume 9, Issue 1 [Number 26], 2001 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 09/10/2021 02:39:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30868 The Official Publication of The Historical Diving Societies of South East Asia & Pacific, Canada, Germany, Mexico and the U.S.A. Volume 9 Issue 1 Winter 2001 The Return of the Lama • Hugh Bradner's Wet Suit • Kenny Knott • Lowell Thomas Awards • • Antibes Diving History Seminar • Divair Regulator • E.R. Cross Files • • Anderson's Tales • ADCI, NOGI and DEMA Awards • Bud Swain • HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION 340 S KELLOGG AVE STE E, GOLETACA 93117, U.S.A. PHONE: 805-692-0072 FAX: 805-692-0042 e-mail: [email protected] or HTTP:I/www.hds.org/ ADVISORY BOARD FOUNDING BENEFACTORS Dr. Sylvia Earle Prof. Hans Hass Art Bachrach, Ph.D. Leslie Leaney Dr. Peter B. Bennett Lotte Hass Antonio Badias-Alonso Robert & Caroline Leaney Dick Bonin Dick Long Roger Bankston Andy Lentz Ernest H. Brooks II J. Thomas Millington, M.D. Ernie Brooks II A.L. "Scrap" Lundy Scott Carpenter Bob & Bill Meistrell Ken & Susan Brown Jim Mabry Wayne Brusate Andrew R. Mrozinski Jean-Michel Cousteau Bev Morgan P.K. Chandran Dr. Phil Nuytten E.R. Cross (1913-2000) Phil Nuytten Steve Chaparro Ronald E. Owen Henri Delauze Sir John Rawlins John Rice Churchill Torrance Parker Andre Galerne Andreas B. Rechnitzer, Ph.D. Raymond I. Dawson, Jr. Alese & Morton Pechter Lad Handelman Robert Stenuit Jesse & Brenda Dean Bob Ratcliffe Les Ashton Smith Diving Systems International Lee Selisky Skip & Jane Dunham Robert D. -

Blood ^ Relations

.S5 BLOOD ^ RELATIONS at« *-^ % ^m^ ^> 4F OYSTER PERPETUAL SUBMARINER DATE ARE FOR AN OFFICIAL ROLEX JEWELER CALL I -800-367-6539. ROLEX * OYSTER PERPETUAL AND SUBMARINER TRADEMARKS NEW YORK DAVID DOUBILET .Underwater photographer. Explorer. Artist. Marine naturalist and protector of the ocean habitat. Author of a dozen books on the sea. For 50 years, his passion has illuminated the hidden depths of the earth. \ ROLEX. ACROWN FOR EVERY ACHIEVEMENT. They'll remember this year forever Why not give them a gift that will last that long? THE 2008 UNITED STATES MINT SILVER PROOF SET" IS HERE — $44.95 No doubt someone in your life is celebrating something special this year. Mark the occasion with a timeless silver proof set, featuring great Americans in sharp detail. Seven coins are struck in 90% silver, and all are encased in special display lenses. These extraordinarily brilliant coins are a perfect way to commemorate a birthday or other milestone. It's a gift they'll appreciate for years to come. FOR GENUINE UNITED STATES MINT PRODUCTS, VISIT WWW.USMINT.GOV OR CALL 1.800. USA. MINT. GENUINELY WORTHWHILE ) UNITED STATES MINT ©2008 United States Mint r .i\ i www.naturamistorymaq.com NOVEMBER 2008 VOLUME 117 NUMBER 9 FE ATU R ES COVER STORY 22 THE CURIOUS, BLOODY LIVES OF VAMPIRE BATS Some of the most highly specialized mammals on the planet have adapted in fascinating ways to a blood diet. BY BILL SCHUTT 28 ICE ON THE EDGE The fate of West Antarctica's ice shelves may determine how far sea level rises around the world. -

2018 Impact Report

EDUCATION + REHABILITATION + RESEARCH + CONSERVATION 2018 Impact Report 2018 From blue-green algae to red tide, our campus Letter from the CEO took evasive action to keep our most important Contents residents, LMC’s sea turtle patients, safe from Introduction 1 and Board Chair our evolving environment. Conservation 3 35 Years of Impact: The year 2018 was very special Juno Beach Pier 6 “The sea turtle tells us the health of the ocean, and in Loggerhead Marinelife Center’s (LMC) history. the ocean tells us the health of our planet.” We th Education 7 In 2018 we celebrated our 35 birthday and share our planet with wildlife, and we know that Research 9 reached record levels of impact. we have one Earth. There is no Plan(et) B. These Rehabilitation 11 Record Awareness and Action: two statements fuel our passion for progress and Marketing & Communications 13 The year 2018 also brought with it a monumental help to unify us all. Blue Friends/Go Blue Awards 15 shift in the global ocean conservation conversation with the following key inflection points: Over 35 years ago, LMC’s founder Eleanor Fletcher Retail Operations 16 • April, Earth Day, dedicated to reducing plastics set us on a course to create an indelible legacy. Capital Expansion Campaign 17 in our world’s ocean Today as we move forward with our Waves of Progress expansion campaign, we have the Signature Events 21 • June, National Geographic’s iconic “Planet or opportunity to significantly amplify and accelerate Circle of 100 22 Plastic” issue is published • July, Plastic drinking straws serve as the icon our conservation and education impact.