Skipaon River Restoration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices Appendix A

APPENDICES APPENDIX A HISTORY OF SKIPANON RIVER WATERSHED Prepared by Lisa Heigh and the Skipanon River Watershed Council Appendix A - Skipanon River Watershed History 2 APPENDIX A HISTORY Skipanon River Watershed Natural History TIMELINE · 45 million years ago - North American Continent begins collision with Pacific Ocean Seamounts (now the Coast Range) · 25 million years ago Oregon Coast began to emerge from the sea · 20 million years ago Coast Range becomes a firm part of the continent · 15 million years ago Columbia River Basalt lava flows stream down an ancestral Columbia River · 12,000 years ago last Ice Age floods scour the Columbia River · 10,000 years ago Native Americans inhabit the region (earliest documentation) - Clatsop Indians used three areas within the Skipanon drainage as main living, fishing and hunting sites: Clatsop Plains, Hammond and a site near the Skipanon River mouth, where later D.K. Warren (Warrenton founder) built a home. · 4,500 years ago Pacific Ocean shoreline at the eastern shore of what is now Cullaby Lake · 1700’s early part of the century last major earthquake · 1780 estimates of the Chinook population in the lower Columbia Region: 2,000 total – 300 of which were Clatsops who lived primarily in the Skipanon basin. · 1770’s-1790’s Robert Gray and other Europeans explore and settle Oregon and region, bringing with them disease/epidemic (smallpox, malaria, measles, etc.) to native populations · 1805-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition, camp at Fort Clatsop and travel frequently through the Skipanon Watershed -

Plate 5. Flood Hazard Map of Clatsop County, Oregon, Appendix E Map

Natural Hazard Risk Report for Clatsop County, Oregon G E O L O G Y F A N O D T N M I E N M E T R R A A L PLATE 5 P I E N Flood Hazard Map of D D U N S O T G R E I R E S O Clatsop County, Oregon WASHINGTON 1937 Flood Hazard Zone 100-Year Flood (1% annual chance) Columbia River sourcesThe �lood include hazard riverine. data show Areas areas are consistentexpected to with be inundated during a 100-year �lood event. Flooding Counties Digital Flood Insurance Rate Maps. the regulatory �lood zones depicted in Clatsop Astoria ¤£101 30 Warrenton «¬104 ¤£ Skipanon River Svensen-Knappa Disclaimer: This product is for informational purposes and may not have been prepared for or be suitable for John Day River Westport legal, engineering, or surveying purposes. Users of this information should review or consult the primary Wallooskee River Ra�o of Es�mated Loss to Flooding data and information sources to ascertain the usability Flood Scenarios of the information. This publication cannot substitute 10-Year 50-Year 100-Year 500-Year ¤£101 for site-speci�ic investigations by quali�ied Exposure Ratio differ from the results shown in the publication. See thepractitioners. accompanying Site-speci�ic text report data for may more give details results on that the ~ ~ «¬202 0% 0.5% 1% 4.5% limitations of the methods and data used to prepare Clatsop County this publication. (rural)* Y o Arch Cape* Gearhart u ng s Ri Svensen-Knappa* ver Seaside Lewis a This map is an overview map and not intended to nd Westport* C er provide details at the community scale. -

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resources Program Center Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/055 ON THE COVER Upper left, Fort Clatsop, NPS Photograph Upper right, Cape Disappointment, Photograph by Kristen Keteles Center left, Ecola, NPS Photograph Lower left, Corps at Ecola, NPS Photograph Lower right, Young’s Bay, Photograph by Kristen Keteles Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/055 Dr. Terrie Klinger School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Rachel M. Gregg School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Jessi Kershner School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Jill Coyle School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Dr. David Fluharty School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 This report was prepared under Task Order J9W88040014 of the Pacific Northwest Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit (agreement CA9088A0008) September 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resources Program Center Fort Collins, CO i The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. -

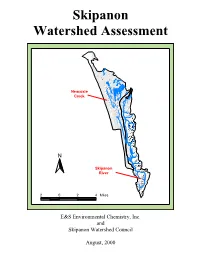

Skipanon Watershed Assessment

Skipanon Watershed Assessment Neacoxie Creek N Skipanon River 2 0 2 4 Miles E&S Environmental Chemistry, Inc. and Skipanon Watershed Council August, 2000 Skipanon River Watershed Assessment Final Report August, 2000 A report by: E&S Environmental Chemistry, Inc. and Skipanon River Watershed Council Joseph M. Bischoff Richard B. Raymond Kai U. Snyder Lisa Heigh and Susan K. Binder Skipanon River Watershed Assessment August, 2000 Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ............................................................ vi LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................... viii ADKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................... ix CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Scope ............................................... 1-1 1.1.1 The Decision Making Framework ............................. 1-1 1.1.2 Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Data Used in this Assessment ............................................... 1-2 1.1.3 Data Confidence ........................................... 1-7 1.2 Setting ........................................................ 1-8 1.3 Ecoregions .................................................... 1-11 1.4 Population .................................................... 1-11 1.5 Climate and Topography ......................................... 1-13 1.6 Geology ...................................................... 1-13 1.7 Vegetation .................................................... 1-13 1.7.1 Large Conifers -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Oregon Byway Highway # "Pacific Coast Scenic Byway - Oregon"

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Oregon Byway Highway # "Pacific Coast Scenic Byway - Oregon" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Brookings, Oregon Brookings, Oregon, located on the West coast of the USA, along the Pacific Ocean. Winter Art & Chocolate Festival, is a famous festival held in Brookings, Oregon on the second weekend of February, when local and regional artists and chocolatiers perform. The Brookings Harbor Festival of the Arts, takes place the third weekend in August on the Boardwalk at the Port of Brookings Harbor. This is where Pacific Coast Scenic Byway starts its northerly run on the south towards Astoria, Oregon. This byway provides amazing coastal scenery, passes through agricultural valleys and brushes against wind-sculpted dunes, clings to seaside cliffs, and winds by estuarine marshes. Along the route are small towns, historic bridges and lighthouses, museums, overlooks, and state parks. 1.2 Brookings Airport Parkview Drive, Beach Avenue, Brookings Airport, a public airport located northeast of the city of Brookings in Curry County, Oregon, Garvins Heliport, a private heliport located north of Brookings in Curry County, Oregon, 1.3 Harris Beach State Park, Harris Beach State Park, an Oregon State Park located on US Highway 101, north of Brookings. Harris Beach State Park is home to Bird Island (also known as Goat Island), which is reported to be the largest island off the Oregon Coast and is a National Wildlife Refuge. 2.2 Carpenterville Road Carpenterville Road, Forest Wayside State Park, 3.5 Samuel H. Board State Samuel H. Boardman State Scenic Corridor, a linear state park in Scenic Corridor southwestern Oregon, It is a twelve miles long and thickly forested along steep and rugged coastline with a few small sand beaches. -

City of Warrenton Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Addendum

City of Warrenton Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Addendum Prepared for City of Warrenton 225 S. Main Avenue Warrenton, Or 97146 In cooperation with Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce (CREST) 750 Commercial Street, Room 205 Astoria, OR 97103 Adopted by the Warrenton City Commission on January 26, 2010 Volume III: City Addendum City of Warrenton Overview The city of Warrenton developed this addendum to the Clatsop County Multi- jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan in an effort to increase the community’s resilience to natural hazards. The addendum focuses on the natural hazards that could affect Warrenton, Oregon, which include coastal erosion, drought, earthquake, flood, landslide, tsunami, volcano, wildfire, wind storm, and winter storm. It is impossible to predict exactly when disasters may occur, or the extent to which they will affect the city. However, with careful planning and collaboration among public agencies, private sector organizations, and citizens within the community, it is possible to minimize the losses that can result from natural hazards. The addendum provides a set of actions that aim to reduce the risks posed by natural hazards through education and outreach programs, the development of partnerships, and the implementation of preventative activities such as land use or watershed management programs. The actions described in the addendum are intended to be implemented through existing plans and programs within the city. The addendum is comprised of the following sections: 1) How was the Addendum Developed? 2) Community Profile; 3) Risk Assessment; 4) Mission, Goals, and Action Items; and 5) Plan Implementation and Maintenance. How was the Addendum Developed? In the fall of 2006, the Oregon Partnership for Disaster Resilience (OPDR) at the University of Oregon’s Community Service Center partnered with Oregon Emergency Management (OEM) and Clatsop and Lincoln Counties to develop a Pre- Disaster Mitigation Planning Grant proposal. -

Changes in Columbia River Estuary Habitat Types Over the Past Century

'E STEVE, P, CHANGES IN COLUMBIA RIVER ESTUARY HABITAT TYPES OVER THE PAST CENTURY Duncan W. Thomas July 1983 COLUMBIA RIVER ESTUARY DATA DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce P.O. Box 175 Astoria, Oregon 97103 (503) 325-0435 The preparation of this report was financially aided through a grant from the Oregon State Department of Energy with funds obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and appropriated for Section 308(b) of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. Editing and publication funds were provided by the Columbia River Estuary Data Development Program. I I I I I I AUTHOR Duncan W. Thomas I I I I EDITOR I Stewart J. Bell I I I I I I iii FOREWORD Administrative Background This study was undertaken to meet certain regulatory requirements of the State of Oregon. On the Oregon side of the Columbia River Estuary, Clatsop County and the cities of Astoria, Warrenton and Hammond are using the resources of the Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce (CREST) to bring the estuary-related elements of their land and water use plans into compliance with Oregon Statewide Planning Goals and Guidelines. This is being accomplished through the incorporation of CREST's Columbia River Estuary Regional Management Plan (McColgin 1979) into the local plans. Oregon Statewide Planning Goal 16, Estuarine Resources, adopted by the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) in December 1976, requires that "when dredge or fill activities are permitted in inter-tidal or tidal marsh areas, their effects shall be mitigated by creation or restoration of another area of similar biological potential... -

Some Recent Physical Changes of the Oregon Coast

rOREGON STATE UNIVERS TY LIBRARIES IIIIII 111IIIII1 IIII III 12 0002098016 65458 .8 05 cop .3 FINAL RE PORT (Report on an investigation carried out under Contract Nonr-2771 (04), Project NR 388-062, between the University of Oregon and the Office of Naval Research, U. S. Department of the Navy.) Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted for any purpose of the United States Government. SOME RECENT PHYSICAL CHANGES OF THE OREGON COAST by Samuel N. Dicken assisted by Carl L. Johannessen and Bill Hanneson Department of Geography University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon November 15, 1961 Reprinted in the public interest by the EugeneRegister-Guard and the Lane County Geographical Society,Inc., April, 1976. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The subject of coastal changes is of interest to many people living on or near the Oregon coast and, as a result, numerous interviews, only a few of which can be acknowledged, furnished much information not otherwise available. Valuable assistance came from persons concerned professionally with some aspect of coastal change. The staff of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Portland District, was most helpful, especially H. A. Kidby of the Rivers and Harbors Section, Lloyd Ruff of the Geology Section, Mr. Charles Oros of the Photogrammetry Office and Dorothy McKean, Librarian. Mr. E. Olson of the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey located copies of old charts and other materials.Ralph Mason of the Oregon State Department of Geology and Mineral Industriescon- tributed notes on Ecola Park and other areas. Robert L. Brown and the staff of the U. S. Soil Conservation Service furnished photographs andspec- ific information on vegetation changes of the dunes.Park Snavely of the U. -

Douglas Deur Empires O the Turning Tide a History of Lewis and F Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region

A History of Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks and the Columbia-Pacific Region Douglas Deur Empires o the Turning Tide A History of Lewis and f Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region Douglas Deur 2016 With Contributions by Stephen R. Mark, Crater Lake National Park Deborah Confer, University of Washington Rachel Lahoff, Portland State University Members of the Wilkes Expedition, encountering the forests of the Astoria area in 1841. From Wilkes' Narrative (Wilkes 1845). Cover: "Lumbering," one of two murals depicting Oregon industries by artist Carl Morris; funded by the Work Projects Administration Federal Arts Project for the Eugene, Oregon Post Office, the mural was painted in 1942 and installed the following year. Back cover: Top: A ship rounds Cape Disappointment, in a watercolor by British spy Henry Warre in 1845. Image courtesy Oregon Historical Society. Middle: The view from Ecola State Park, looking south. Courtesy M.N. Pierce Photography. Bottom: A Joseph Hume Brand Salmon can label, showing a likeness of Joseph Hume, founder of the first Columbia-Pacific cannery in Knappton, Washington Territory. Image courtesy of Oregon State Archives, Historical Oregon Trademark #113. Cover and book design by Mary Williams Hyde. Fonts used in this book are old map fonts: Cabin, Merriweather and Cardo. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series Publication Number 2016-001 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior ISBN 978-0-692-42174-1 Table of Contents Foreword: Land and Life in the Columbia-Pacific -

Plate 6. Landslide Susceptibility Map of Clatsop County, Oregon

Natural Hazard Risk Report for Clatsop County, Oregon G E O L O G Y F A N O D T N M I E N M E T R R A A L PLATE 6 P I E N Landslide Susceptibility Map of D D U N S O T G R E I R E S O Clatsop County, Oregon WASHINGTON 1937 Landslide Suscep�bility Landslide susceptibility is categorized as Low, Moderate, High, and Very High which describes the Low general level of susceptibility to landslide hazard. The Columbia River Moderate dataset is an aggregation of three primary sources: landslide inventory (SLIDO), generalized geology, and High slope. Very High Astoria ¤£101 30 Warrenton «¬104 ¤£ Skipanon River Svensen-Knappa Disclaimer: This product is for informational purposes and may not have been prepared for or be suitable for John Day River Westport legal, engineering, or surveying purposes. Users of this information should review or consult the primary Wallooskee River Ra�o of Building Value Exposed to Landslide data and information sources to ascertain the usability Landslide Suscep�bility of the information. This publication cannot substitute Low Moderate High Very High ¤£101 for site-speci�ic investigations by quali�ied Exposure percentage differ from the results shown in the publication. See thepractitioners. accompanying Site-speci�ic text report data for may more give details results on that the «¬202 0% 40% 80% limitations of the methods and data used to prepare Clatsop County this publication. (rural)* Y o Arch Cape* Gearhart u ng s Ri Svensen-Knappa* ver Seaside Lewis a This map is an overview map and not intended to nd Westport* C er provide details at the community scale. -

Landforms Along the Lower Columbia River and the Influence of Humans

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 4-10-2015 Landforms along the Lower Columbia River and the Influence of Humans Charles Matthew Cannon Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geomorphology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cannon, Charles Matthew, "Landforms along the Lower Columbia River and the Influence of Humans" (2015). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2231. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2228 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Landforms along the Lower Columbia River and the Influence of Humans by Charles Matthew Cannon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology Thesis Committee: Andrew G. Fountain, Chair Jim E. O’Connor Scott F. Burns Portland State University 2015 Abstract River systems, such as the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest, USA have been influenced by human activities, resulting in changes to the physical processes that drive landform evolution. This work describes an inventory of landforms along the Columbia River estuary between the Pacific Ocean and Bonneville Dam in Oregon and Washington. Groupings of landforms are assigned to formative process regimes that are used to assess historical changes to floodplain features. The estuary was historically a complex system of channels with a floodplain dominated by extensive tidal wetlands in the lower reaches and backswamp lakes and wetlands in upper reaches. -

Lower Columbia River Guide

B OATING G UIDE TO THE Lower Columbia & Willamette Rivers The Oregon State Marine Board is Oregon’s recreational boating agency. The Marine Board is dedicated to safety, education and access in an enhanced environment. The Extension Sea Grant Program, a component of the Oregon State University Extension Service, provides education, training, and technical assistance to people with ocean-related needs and interests. As part of the National Sea Grant Program, the Washington Sea Grant Marine Advisory Services is dedicated to encouraging the understanding, wise use, development, and con- servation of our ocean and coastal resources. The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission acquires, operates, enhances and protects a diverse system of recreational, cultural, historical and natural sites. The Commission fosters outdoor recreation and education statewide to provide enjoyment and enrichment for all and a valued legacy for future generations. SMB 250-424-2/99 OSU Extension Publication SG 86 First Printing May, 1992 Second Printing November, 1993 Third Printing October, 1995 Fourth Printing February, 1999 Fifth Printing September, 2003 Sixth Printing June, 2007 Extension Service, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Lyla Houglum, director. This publication was produced and distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress of May 8 and June 30, 1914. Extension work is a cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Oregon counties. The Extension Sea Grant Program is supported in part by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materials - without regard to race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability - as required by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of Education Amendments of 1972, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.