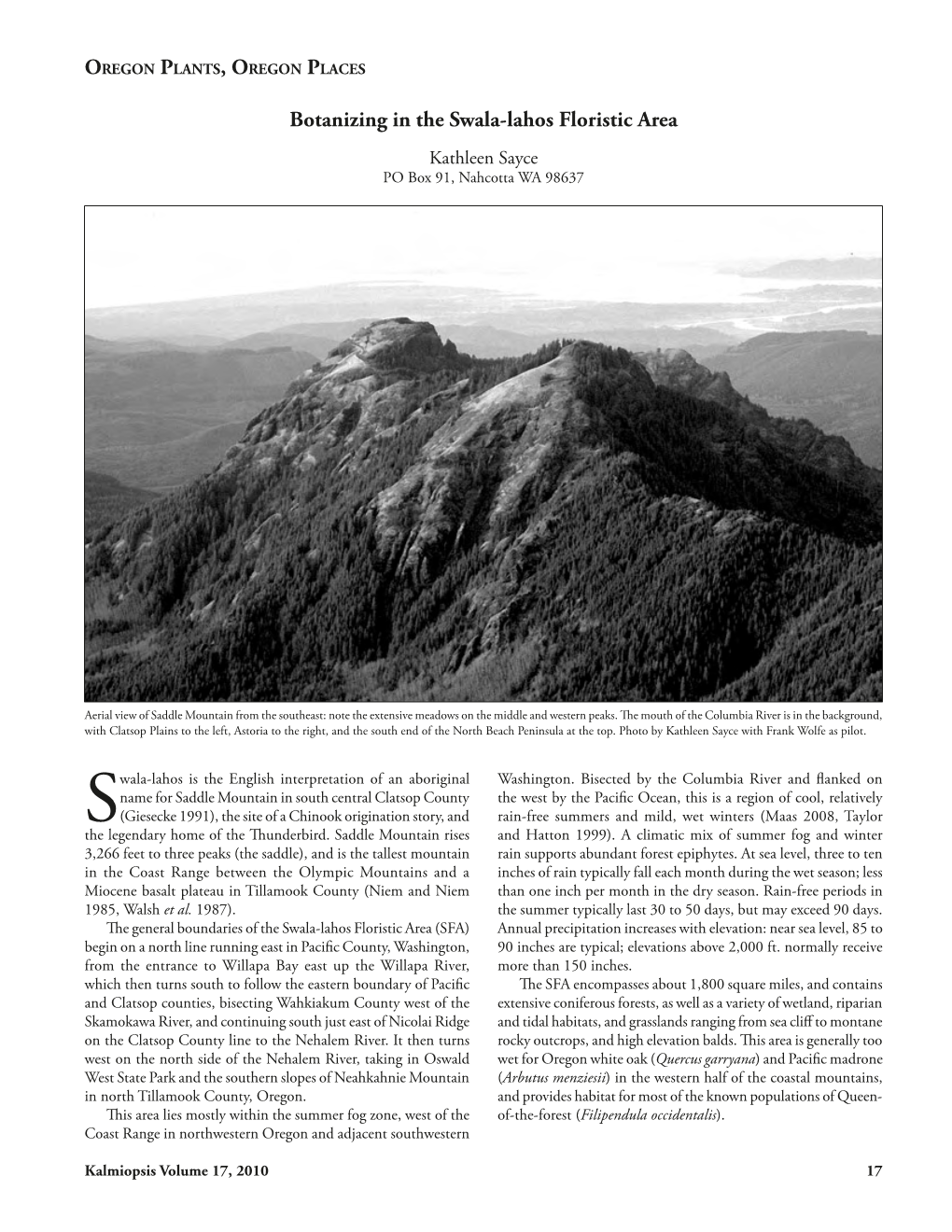

Botanizing in the Swala-Lahos Floristic Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioenergy Harvest, Climate Change, and Forest Carbon in the Oregon Coast Range

Portland State University PDXScholar Environmental Science and Management Faculty Publications and Presentations Environmental Science and Management 3-2016 Bioenergy Harvest, Climate Change, and Forest Carbon in the Oregon Coast Range Megan K. Creutzburg Portland State University, [email protected] Robert M. Scheller Portland State University, [email protected] Melissa S. Lucash Portland State University, [email protected] Louisa B. Evers Bureau of Land Management Stephen D. LeDuc United States Environmental Protection Agency See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/esm_fac Part of the Forest Biology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Creutzburg, M. K., Scheller, R. M., Lucash, M. S., Evers, L. B., LeDuc, S. D., & Johnson, M. G. (2015). Bioenergy harvest, climate change, and forest carbon in the Oregon Coast Range. GCB Bioenergy. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Science and Management Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Megan K. Creutzburg, Robert M. Scheller, Melissa S. Lucash, Louisa B. Evers, Stephen D. LeDuc, and Mark G. Johnson This article is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/esm_fac/118 GCB Bioenergy (2016) 8, 357–370, doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12255 Bioenergy harvest, climate change, and forest carbon in the Oregon Coast Range MEGAN K. CREUTZBURG1 , ROBERT M. SCHELLER1 , MELISSA S. LUCASH1 , LOUISA B. EVERS2 , STEPHEN D. LEDUC3 and MARK G. -

The Oregon Coast Range- Considerations for Ecological Restoration Joe Means Tom Spies Shu-Huei Chen Jane Kertis Pete Teensma

Forests of the Oregon Coast Range- Considerations for Ecological Restoration Joe Means Tom Spies Shu-huei Chen Jane Kertis Pete Teensma The Oregon Coast Range supports some of the most dense Ocean, so they are warm and often highly productive, com- and productive forests in North America. In the pre-harvest- pared to the Cascade Range and central Oregon forests. ing period these forests arose as a result of large fires-the Isaac's (1949) site index map shows much more site class I largest covering 330,000 ha (Teensma and others 1991). and I1 land in the Coast Range than in the Cascades. In the These fires occurred mostly at intervals of 150 to 300 years. summers, humid maritime air creates a moisture gradient The natural disturbance regime supported a diverse fauna from the coastal western hemlock-Sitka spruce (Tsuga and large populations of anadromous salmonids (salmon heterophylla-Piceasitchensis) zone with periodic fog extend- and related fish). In contrast, the present disturbance re- ing 4 to 10 km inland, through Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga gime is dominated by patch clearcuts of about 10-30 ha menziesii var. rnenziesii)-western hemlock forests in the superimposed on most of the forest land with agriculture on central zone to the drier interior-valley foothill zone of the flats near rivers. Ages of most managed forests are less Douglas-fir, bigleaf maple (Acer rnacrophyllum)and Oregon than 60 years. This logging has coincided with significant oak (Quercus garryana). declines in suitable habitat and populations of some fish and wildlife species. Some of these species have been nearly extirpated. -

Mill Creek Watershed Assessment

Yamhill Basin Council Mill Watershed Assessment December 30, 1999 Funding for the Mill Assessment was provided by the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board and Resource Assistance for Rural Environments. Mill Assessment Project Manager: Robert J. Bower, Principal Author Co-authors: Chris Lupoli, Linfield College intern, for Riparian section and assisted with Wetlands Conditions section. Tamara Quandt, Linfield College intern, for Sensitive Species section. Editors: Melissa Leoni, Yamhill Basin Council, McMinnville, OR Alison Bower, Forest Ecologist, Corvallis, OR Contributors: Bill Ferber, Salem, Water Resources Department (WRD) Chester Novak, Salem, Bureau Land Management (BLM) Dan Upton, Dallas, Willamette Industries David Anderson, Monmouth, Boise Cascade Dean Anderson, Dallas, Polk County Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Dennis Ades, Salem, Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Gary Galovich, Corvallis, Oregon Department Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) Mark Koski, Salem, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Patrick Hawe, Salem, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Rob Tracey, McMinnville, Natural Resource and Conservation Service (NRCS) Stan Christensen, McMinnville, Yamhill Soil Water Conservation District Susan Maleki, Corvallis, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (OWEB) Warren Tausch, Tillamook Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Special Thanks: ! John Cruickshank, Gooseneck Creek resident for his assistance with the Historical, and Channel Modification sections and in the gathering of historical photographs. ! Gooseneck Creek Watershed Group for their support and guidance. ! John Caputo, Yamhill County GIS. ! BLM and Polk County GIS for providing some of the GIS base layers used to create the maps in this assessment. ! USDA Service Center, Natural Resource Conservation Service, McMinnville, for copying and office support. ! Polk and Yamhill Soil and Water Conservation Districts. ! Nick Varnum, PNG Environmental Inc., Tigard, for assisting with the Hydrology and Channel Habitat Typing sections. -

"Preserve Analysis : Saddle Mountain"

PRESERVE ANALYSIS: SADDLE MOUNTAIN Pre pare d by PAUL B. ALABACK ROB ERT E. FRENKE L OREGON NATURAL AREA PRESERVES ADVISORY COMMITTEE to the STATE LAND BOARD Salem. Oregon October, 1978 NATURAL AREA PRESERVES ADVISORY COMMITTEE to the STATE LAND BOARD Robert Straub Nonna Paul us Governor Clay Myers Secretary of State State Treasurer Members Robert Frenkel (Chairman), Corvallis Bill Burley (Vice Chainnan), Siletz Charles Collins, Roseburg Bruce Nolf, Bend Patricia Harris, Eugene Jean L. Siddall, Lake Oswego Ex-Officio Members Bob Maben Wi 11 i am S. Phe 1ps Department of Fish and Wildlife State Forestry Department Peter Bond J. Morris Johnson State Parks and Recreation Branch State System of Higher Education PRESERVE ANALYSIS: SADDLE MOUNTAIN prepared by Paul B. Alaback and Robert E. Frenkel Oregon Natural Area Preserves Advisory Committee to the State Land Board Salem, Oregon October, 1978 ----------- ------- iii PREFACE The purpose of this preserve analysis is to assemble and document the significant natural values of Saddle Mountain State Park to aid in deciding whether to recommend the dedication of a portion of Saddle r10untain State Park as a natural area preserve within the Oregon System of I~atural Areas. Preserve management, agency agreements, and manage ment planning are therefore not a function of this document. Because of the outstanding assemblage of wildflowers, many of which are rare, Saddle r·1ountain has long been a mecca for· botanists. It was from Oregon's botanists that the Committee initially received its first documentation of the natural area values of Saddle Mountain. Several Committee members and others contributed to the report through survey and documentation. -

Geologic History of Siletzia, a Large Igneous Province in the Oregon And

Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Wells, R., Bukry, D., Friedman, R., Pyle, D., Duncan, R., Haeussler, P., & Wooden, J. (2014). Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot. Geosphere, 10 (4), 692-719. doi:10.1130/GES01018.1 10.1130/GES01018.1 Geological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Downloaded from geosphere.gsapubs.org on September 10, 2014 Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Ray Wells1, David Bukry1, Richard Friedman2, Doug Pyle3, Robert Duncan4, Peter Haeussler5, and Joe Wooden6 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025-3561, USA 2Pacifi c Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, 6339 Stores Road, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1680 East West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, 104 CEOAS Administration Building, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-5503, USA 5U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4626, USA 6School of Earth Sciences, Stanford University, 397 Panama Mall Mitchell Building 101, Stanford, California 94305-2210, USA ABSTRACT frames, the Yellowstone hotspot (YHS) is on southern Vancouver Island (Canada) to Rose- or near an inferred northeast-striking Kula- burg, Oregon (Fig. -

Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwestern Oregon Coast Range (Neskowin, Nestucca Bay, Hebo, and Dolph 7.5 Minute Quadrangles)

(a-0g) R ago (na. 96-53 14. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR , U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Alatzi2/6 (Of (c,c) - R qo rite 6/6-53y Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwestern Oregon Coast Range (Neskowin, Nestucca Bay, Hebo, and Dolph 7.5 minute Quadrangles) by Parke D. Snavely, Jr.', Alan Niem 2 , Florence L. Wong', Norman S. MacLeod 3, and Tracy K. Calhoun 4 with major contributions by Diane L. Minasian' and Wendy Niem2 Open File Report 96-0534 1996 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American stratigraphic code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1/ U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA 94025 2/ Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97403 3/ Consultant, Vancouver, WA 98664 4/ U.S. Forest Service, Corvallis, OR 97339 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 GEOLOGIC SKETCH 2 DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS SURFICIAL DEPOSITS 7 BEDROCK UNITS Sedimentary and Volcanic Rocks 8 Intrusive Rocks 14 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 15 REFERENCES CITED 15 MAP SHEETS Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwestern Oregon Coast Range, scale 1:24,000, 2 sheets. Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwest Oregon Coast Range (Neskowin, Nestucca Bay, Hebo, and Dolph 7.5 minute Quadrangles) by Parke D. Snavely, Jr., Alan Niem, Florence L. Wong, Norman S. MacLeod, and Tracy K. Calhoun with major contributions by Diane L. Minasian and Wendy Niem INTRODUCTION The geology of the Cascade Head (W.W. -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

Vol . 37, No.2 Februory 1975 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES The Ore Bin Published Monthly By STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOlOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 Stote Office Bldg., Portland, Oregon - 97201 Telephone, [503) - 229-5580 FIELD OFFICES 2033 First Street 521 N. E. "E" Street Baker 97814 Grants Pass 97526 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Subscription Rate 1 year - $2.00; 3 years - $5.00 Available back issues - $.25 eoch Second closs postage paid at Portland, Oregon GOVERNI NG BOARD R. W . deWeese, Portland, Chairman Willian E. Miller, Bend H. lyle Van Gordon, Grants Pass STATE GEOLOGIST R. E. Corcoran GEOlOGISTS IN CHARGE OF FIELD OFFICES Howard C. Brooks, Baker len Ramp, Gronfl Pass Permiuion il gronted to reprint information contained h..... in. Credit given the State of Oregon D~hMnt of Geology and Min.ollndustries for compiling this information will be appreciated. Sio l e of Oregon The ORE BIN DeporlmentofGeology and Minerollndultries Volume 37, No.2 1069 Siole Office Bldg. February 1975 P«tlond Oregon 97201 GEOLOGY OF HUG POINT STATE PARK NORTHERN OREGON COAST Alan R. Niem Deparhnent of Geology, Oregon State University Hug Point State Park is a strikingly scenic beach and recreational area be tween Cannon Beach and Arch Cape on the northern coast of Oregon (Fig ure 1) . The park is situated just off U.S . Highway 101, 4 miles south of Cannon Beach (Figure 2). It can be reached from Portland via the Sunset Highway (U.S. 26) west toward Seaside, then south. 00 U.S . 101 at Cannon Beach Junction. -

Shipwreck Traditions and Treasure Hunting on Oregon's North Coast

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology Summer 2018 The Mountain of a Thousand Holes: Shipwreck Traditions and Treasure Hunting on Oregon's North Coast Cameron La Follette Oregon Coast Alliance Dennis Griffin Oregon State Historic Preservation Office Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Cameron La Follette, Dennis Griffin, & Douglas Deur. (2018). The Mountain of a Thousand Holes: Shipwreck Traditions and Treasure Hunting on Oregon's North Coast. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 119(2), 282-313. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Mountain of a Thousand Holes Shipwreck Traditions and Treasure Hunting on Oregon’s North Coast CAMERON LA FOLLETTE, DENNIS GRIFFIN, AND DOUGLAS DEUR EURO-AMERICANS in coastal communities conflated and amplified Native American oral traditions of shipwrecks in Tillamook County, increasingly focusing the stories on buried treasure. This focus led to a trickle, and then a procession, of treasure-seekers visiting the northern Oregon coast, reach- ing full crescendo by the mid to late twentieth century. The seekers’ theo- ries ranged from the fairly straightforward to the wildly carnivalesque, with many bizarre permutations. Neahkahnie Mountain and its beaches became the premier treasure-hunting sites in Oregon, based on the mountain’s prominence in popular lore, linked to unverified stories about the wreck of a Spanish ship. -

Drainage Basin Morphology in the Central Coast Range of Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WENDY ADAMS NIEM for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in GEOGRAPHY presented on July 21, 1976 Title: DRAINAGE BASIN MORPHOLOGY IN THE CENTRAL COAST RANGE OF OREGON Abstract approved: Redacted for privacy Dr. James F. Lahey / The four major streams of the central Coast Range of Oregon are: the westward-flowing Siletz and Yaquina Rivers and the eastward-flowing Luckiamute and Marys Rivers. These fifth- and sixth-order streams conform to the laws of drain- age composition of R. E. Horton. The drainage densities and texture ratios calculated for these streams indicate coarse to medium texture compa- rable to basins in the Carboniferous sandstones of the Appalachian Plateau in Pennsylvania. Little variation in the values of these parameters occurs between basins on igneous rook and basins on sedimentary rock. The length of overland flow ranges from approximately i mile to i mile. Two thousand eight hundred twenty-five to 6,140 square feet are necessary to support one foot of channel in the central Coast Range. Maximum elevation in the area is 4,097 feet at Marys Peak which is the highest point in the Oregon Coast Range. The average elevation of summits in the thesis area is ap- proximately 1500 feet. The calculated relief ratios for the Siletz, Yaquina, Marys, and Luckiamute Rivers are compara- ble to relief ratios of streams on the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains and on the Appalachian Piedmont. Coast Range streams respond quickly to increased rain- fall, and runoff is rapid. The Siletz has the largest an- nual discharge and the highest sustained discharge during the dry summer months. -

Geologic Formations of Western Oregon

BULLETIN 70 GEOLOGIC fORMATION§ OF WESTERN OREGON WEST OF LONGITUDE 121° 30' STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1971 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1069 Stal·e Office Building Portland, Oregon 97201 BULLETIN 70 GEOLOGIC FORMATIONS OF WESTERN OREGON (WEST OF LONGITUDE 12 1 °30') By John D. Beaulieu 1971 GOVERNING BOARD Fayette I. Bristol, Rogue River, Chairman R. W. deWeese, Portland Harold Banta, Baker STATE GEOLOGIST R. E. Corcoran CONTENTS Introduction . Acknowledgements 2 Geologic formations 3 Quadrang I es. 53 Corre I ation charts. 60 Bibliography. 63 ii GE OLOGIC FORMA T IONS OF WESTERN OR EGON (W E ST OF LONG ITUD E 12 1°30') By John D. Beaulieu* INTRODUCTION It is the purpose of th is publi cation to provide a concise , yet comprehensive discussion of the for mations of western Oregon. It is the further aim that the data for each of the formations be as current as possi ble. Consequently, the emphasis has been placed on th e recent literature . Although this paper should not be viewed as a discussion of the historical development of each of the fo rmations, the original reference for each of the units is given . Also, in cases where the historical development of the formation has a direct bearing on present-day problems it is included in the discussion . A wide variety of published literature and unpublished reports , theses, and dissertations was con sul ted and several professional opin ions regarding specific problems were so licited . In recent years re search has been concentrated in the Klamath Mountains and the southern Coast Range and for these regions literature was volumi nous. -

Skipaon River Restoration

Skipanon River Restoration Action Plan Adopted May, 2006 Background of Project The Skipanon Watershed Council formed in 1997 as a community-based organization to identify and proactively address watershed restoration. In 2004, the council was given funds from a civil penalty suit against a local fish processing plant. The funds are to be used for restoration in the Skipanon Watershed. Before using funds for any restoration projects, the council felt it was important to revise its Action Plan to identify the most ecological significant restoration projects within the watershed. Goal of Project The goals of this document are to identify, analyze and priotizes, to the extent possible, potential site-specific conservation projects within the Skipanon Watershed. The Council hopes to create a document based in sound ecological principles, yet understandable by the lay reader. Additionally, the Council hopes to highlight partnership opportunities, monitoring efforts and educational opportunities. Ultimately, the Council and other watershed related organizations can utilize this document to help guide restoration, conservation and acquisition activities, monitoring and education within watershed. Lastly, the Council hopes the numerical prioritization methodology is transferable to the estuarine portions of the Youngs Bay and Nicolai-Wickiup Watersheds. Methods Summary of Methods The methods to achieve the goals of the project were to 1) involve the public and 2) review and utilize other prioritization criteria. As a community-based organization, it was imperative to involve as many community members, landowners, interested citizens, municipalities and agencies in the process of identifying restoration activities as possible. To identify potential restoration projects, the Council relied on the expertise of local community members, landowners, interested citizens, representatives from local municipalities and agencies. -

Geophysical and Geochemical Analyses of Selected Miocene Coastal Basalt Features, Clatsop County, Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1980 Geophysical and geochemical analyses of selected Miocene coastal basalt features, Clatsop County, Oregon Virginia Josette Pfaff Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geochemistry Commons, Geophysics and Seismology Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Pfaff, Virginia Josette, "Geophysical and geochemical analyses of selected Miocene coastal basalt features, Clatsop County, Oregon" (1980). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3184. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Virginia Josette Pfaff for the Master of Science in Geology presented December 16, 1980. Title: Geophysical and Geochemical Analyses of Selected Miocene Coastal Basalt Features, Clatsop County, Oregon. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Chairman Gi lTfiert-T. Benson The proximity of Miocene Columbia River basalt flows to "locally erupted" coastal Miocene basalts in northwestern Oregon, and the compelling similarities between the two groups, suggest that the coastal basalts, rather than being locally erupted, may be the westward extension of plateau