Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT OF

Case 1:99-cv-02496-PLF Document 6276 Filed 08/03/18 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Plaintiff, ) Civil Action No. 99-CV-2496 (PLF) ) and ) ) CAMPAIGN FOR TOBACCO-FREE ) KIDS, et al., ) Plaintiff-Intervenors, ) ) v. ) ) PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., et al., ) Defendants. ) ) and ) ) ITG BRANDS, LLC, et al., ) Post-Judgment Parties ) Regarding Remedies ) PLAINTIFFS’ 2018 SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF ON RETAIL POINT OF SALE REMEDY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 5 I. The Deal between Cigarette Manufacturers and Retailers ............................................... 5 II. Benefits to Participating Retailers .................................................................................... 6 III. Manufacturers’ Contractual Control over Space for Cigarette Marketing and Promotional Displays ....................................................................................................... 8 A. The types of retail advertising and marketing space ........................................8 B. The manufacturers’ contractual authority over participating retailers’ space 10 1. The -

South Carolina Tobacco Directory

South Carolina Tobacco Directory Updated: June 14, 2019 Office of the Attorney General South Carolina Tobacco Directory Alan Wilson Company Name Brand Name Original Certification Date Agreement type Status Cheyenne International LLC Decade 8/10/2005 NPM Compliant Aura 6/16/2014 NPM Compliant Cheyenne 8/10/2005 NPM Compliant Commonwealth Brands, Inc. USA Gold 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Crowns 3/16/2011 PM Compliant Rave 7/15/2009 PM Compliant Rave (RYO) 7/15/2009 PM Compliant Montclair 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Fortuna 9/15/2008 PM Compliant Sonoma 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Compania Tabacalera Internacional, S.A. Director 12/27/2017 NPM Compliant Dosal Tobacco Corporation 305 8/9/2010 NPM Compliant DTC 8/9/2010 NPM Compliant Firebird Manufacturing Cherokee 8/4/2010 NPM Compliant Palmetto 8/4/2010 NPM Compliant ITG Brands LLC Kool 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Winston 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Salem 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Maverick 8/11/2005 PM Compliant Japan Tobacco International U.S.A., Inc. Wave 8/10/2005 PM Compliant LD by L. Ducat 5/6/2016 PM Compliant Export A 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Kretek International Taj Mahal Bidis 10/18/2005 PM Compliant KT&G Corporation page: 0 of 1 Carnival 2/15/2012 NPM Compliant THIS 2/15/2018 NPM Compliant Timeless Time 2/15/2012 NPM Compliant Liggett Group Inc. Pyramid 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Liggett Select 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Eve 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Bronson 10/4/2011 PM Compliant Grand Prix 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Tourney 9/8/2005 PM Compliant Tourney Slims 8/9/2005 PM Compliant NASCO Products, LLC SF 1/5/2015 PM Compliant Native Trading Associates Mohawk 8/6/2013 NPM Compliant Native 6/14/2006 NPM Compliant Native (RYO) 12/10/2007 NPM Compliant Ohserase Manufacturing Signal 8/1/2011 NPM Compliant Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Turkish Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Danish Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant London Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Amsterdam Shag (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Stockholm Blend (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Norwegian Shag (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Philip Morris USA Inc. -

Tobacco Securitization

Memorandum Office of Jenine Windeshausen Treasurer-Tax Collector To: The Board of Supervisors From: Jenine Windeshausen, Treasurer-Tax Collector Date: October 27, 2020 Subject: Tobacco Securitization Action Requested a) Adopt a resolution consenting to the issuance and sale by the California County Tobacco Securitization Agency not to exceed $67,000,000 initial principal amount of tobacco settlement bonds (Gold Country Settlement Funding Corporation) Series 2020 Bonds in one or more series and other related matters; authorizing the execution and delivery by the county of a certificate of the county; and authorizing the execution and delivery of and approval of other related documents and actions in connection therewith. b) Direct that eligible proceeds from the Series 2020 Bonds be expended on infrastructure improvements at the Placer County Government Center, construction of the Health and Human Services Building and other Board approved capital facilities projects. Background October 6, 2020 Board of Supervisors Meeting Summary. Your Board received an update regarding the County’s prior tobacco securitizations and information on the potential to refund the Series 2006 Bonds to receive additional proceeds for capital projects. Based on that update, the Board requested the Treasurer to return to the Board on October 27, 2020 with a resolution approving documents and other matters to proceed with refunding the Series 2006 Bonds. In summary from the October 6, 2020 meeting, the County receives annual payments in perpetuity from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA). The MSA payments are derived from a percentage of cigarette sales. Placer County issued bonds in 2002 and 2006 to securitize a share of its MSA payments. -

Annual Report 2019 CONTENT

中煙國際 (香港) 有限公司 China Tobacco International (HK) Company Limited (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) Stock code: 6055 Annual Report 2019 CONTENT Definitions 2 Company Information 4 Financial Highlights 5 Chairman’s Statement 6 Management Discussion and Analysis 7 Review of Continuing Connected Transactions 16 Directors and Senior Management 30 Report of the Directors 37 Corporate Governance Report 48 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 2019 60 Independent Auditor’s Report 86 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 91 Statement of Financial Position 92 Statement of Changes in Equity 94 Statement of Cash Flows 95 Notes to the Financial Statements 96 Financial Summary 140 2 China Tobacco International (HK) Company Limited Definitions In this annual report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall have the meanings set forth below. “AGM” annual general meeting of the Company; “Audit Committee” the audit committee of the Board; “Board” or “Board of Directors” the board of Directors of the Company; “China” or “PRC” the People’s Republic of China; for the purpose of this report only, references to “China” or the “PRC” do not include the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Macau Special Administrative Region and Taiwan; “CNTC” China National Tobacco Corporation* (中國煙草總公司), an enterprise incorporated in the PRC and the ultimate controlling shareholder of the Company; “CNTC Group” CNTC and its subsidiaries; “Company” or “we” China Tobacco International (HK) Company Limited -

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

Pyramid Cigarettes

** Pyramid Cigarettes ** Pyramid Red Box 10 Carton Pyramid Blue Box 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Gold Box 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Silver Box 10 Carton Pyramid Orange Box 10 Carton Pyramid Red Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Blue Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Gold Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Silver Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Orange Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Non Filter Box 10 Carton ** E Cigarettes ** Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Gold 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol High 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Platinum 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Sterling 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Zero 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Gold 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette High 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Sterling 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Platinum 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Zero 24 Box ** Premium Cigars ** Acid Krush Classic Blue 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Mad Morado 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Gold 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Red 5-10pk Tin Acid Kuba Kuba 24 Box Acid Blondie 40 Box Acid C-Note 20 Box Acid Kuba Maduro 24 Box Acid 1400cc 18 Box Acid Blondie Belicoso 24 Box Acid Kuba Deluxe 10 Box Acid Cold Infusion 24 Box Ambrosia Clove Tiki 10 Box Acid Larry 10-3pk Pack Acid Deep Dish 24 Box Acid Wafe 28 Box Acid Atom Maduro 24 Box Acid Nasty 24 Box Acid Roam 10 Box Antano Dark Corojo Azarosa 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo El Martillo 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo Pesadilla 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo Poderoso 20 Box Natural Dirt 24 Box Acid Liquid 24 Box Acid Blondie -

Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Marketing Orders for New Cigarettes Marketed by Commonwealth Brands, Inc

Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Marketing Orders for New Cigarettes Marketed by Commonwealth Brands, Inc. Prepared by Center for Tobacco Products U.S. Food and Drug Administration June 26, 2019 1 Table of Contents 1. Applicant and Manufacturing Facility Information ...................................................................... 3 2. Product Information ................................................................................................................... 3 3. The Need for the Proposed Actions ............................................................................................. 4 4. Alternatives to the Proposed Actions .......................................................................................... 4 5. Potential Environmental Impacts of the Proposed Actions and Alternatives – Manufacturing the New Products .......................................................................................................................... 4 5.1. Affected Environment ......................................................................................................... 5 5.2. Air Quality ........................................................................................................................... 6 5.3. Water Resources ................................................................................................................. 6 5.4. Soil, Land Use, and Zoning .................................................................................................. 6 5.5. Biological Resources -

Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nicotine Manuscript Author Tob Res. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 July 01. Published in final edited form as: Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 July ; 18(7): 1575–1580. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv162. Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes Jiu Ai, Ph.D.1, Kenneth M. Taylor, Ph.D.1, Joseph G. Lisko, M.S.2, Hang Tran, M.S.2, Clifford H. Watson, Ph.D.2, and Matthew R. Holman, Ph.D.1 1Office of Science, Center for Tobacco Products, United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD 20993 2Tobacco Products Laboratory, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA Abstract Introduction—In 2011 menthol cigarettes accounted for 32 percent of the market in the United States, but there are few literature reports that provide measured menthol data for commercial cigarettes. To assess current menthol application levels in the U.S. cigarette market, menthol levels in cigarettes labeled or not labeled to contain menthol was determined for a variety of contemporary domestic cigarette products. Method—We measured the menthol content of 45whole cigarettes using a validated gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method (GC/MS). Results—In 23 cigarette brands labeled as menthol products, the menthol levels of the whole cigarette ranged from 2.9 to 19.6 mg/cigarette, with three products having higher levels of menthol relative to the other menthol products. The menthol levels for 22 cigarette products not labeled to contain menthol ranged from 0.002 to 0.07 mg/cigarette. -

Supplementary Files Supplemental Table 1: Tar And

Supplementary Files Supplemental Table 1: Tar and Ventilation Levels of Chinese Cigarette Brands in 2009 and 2012 2009 2012 Tar Tar UPC Brand Name (mg) Ventilated (mg) Ventilated 6901028000642 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028000987 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028001465 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028001618 Shuang Xi 11 Yes 10 Yes 6901028002097 Cocopalm 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028002752 Cocopalm 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028011075 Jiatianxia 13 Yes 13 Yes 6901028015417 Zhenlong 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028024969 The X Catena Pride 8 Yes 8 No 6901028024990 Pride 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028025812 Pride 6 Yes 8 Yes 6901028028356 Tianxiaxiu 14 Yes 14 Yes 6901028036672 Huang Guoshu 13 Yes 13 Yes 6901028036795 Huang Guo Shu 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028037891 Huangguoshu 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028045483 Camellia 13 Yes 12 No 6901028048231 Hongtashan 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028055055 Honghe 12 Yes 13 Yes 6901028055086 Honghe 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028055208 Honghe 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028065078 Lan zhou 13 Yes 8 Yes 6901028065399 Lan zhou 13 Yes 8 Yes 6901028065580 Lan zhou 11 Yes 8 Yes 6901028071468 Zhongnanhai 5 Yes 5 Yes 6901028071499 Zhongnanhai 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028071529 Zhongnanhai 5 No 5 No 6901028071765 Zhongnanhai 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028072458 Beijing 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028072601 Zhongnanhai 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075763 Chunghwa 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075770 Chunghwa 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075831 Double Happiness 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028075992 Double Happiness 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028076333 Memphis Blue 9 Yes 9 Yes 6901028090902 Renmin Dahuitang Ben Xiang 10 No 10 Yes 6901028092944 Renmin Dahuitang 13 Yes 12 Yes -

Fire Standard Compliant Cigarette Brands & Styles

THE STATE OF UTAH Fire Standard Compliant Cigarette Brands and Styles Master Approval List List Design: First Section - Deletions to the list in the last 30 Days Second Section - Additions/Re-Certifications in the last 30 Days Third Section - Main List - Reflects Current Status Updated October 15, 2018 FIRE STANDARD COMPLIANT CIGARETTE BRANDS & STYLES MASTER APPROVAL LIST Page 1 BRANDS NOT RENEWED OR DELETED MANUFACTURER FLAVOR PACKAGE EXPIRATION DATE THIS REPORT NONE BRANDS ADDED OR RECERTIFIED THIS MANUFACTURER FLAVOR PACKAGE CERTIFICATION DATE REPORT Montego Red King Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/6/2019 Montegi Red 100's Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/5/2019 Montego Blue 100's Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/12/2019 Montego Blue Kings Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/11/2019 Montego Orange 100's Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/10/2019 Montego Menthol Gold King Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/6/2019 Montego Menthol Gold 100's Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/5/2019 Montego Menthol Silver King Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/11/2019 Montego Menthol Silver 100's Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/12/2019 Teton #18 Blue Kings Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 8/25/2017 Teton #18 Green Menthol Kings Wind River Tobacco., LLC Menthol Filter Hard Pack 11/30/2017 Teton #18 Yellow Kings Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 9/1/2017 Teton #18 Red 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 11/27/2017 Teton #6 Gold 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 11/28/2017 Teton #6 Green Menthol 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC Menthol Filter Hard Pack 11/29/2017 Teton #6 Black Menthol 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC Menthol Filter Hard Pack 11/29/2017 Vantage Classic Menthol 100's Soft Pack R.J. -

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

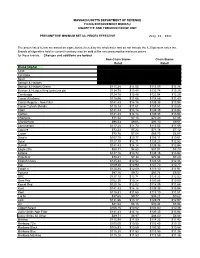

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Moloch! Moloch! Robot Apartments!

MOLOCH! MOLOCH! ROBOT APARTMENTS! __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Literature (MA) __________________ By Janet Whitson Burns December 2014 MOLOCH! MOLOCH! ROBOT APARTMENTS! . By Janet Whitson Bums Approved: Date: E. J. Murphy, Ph.D. 1 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Carry On ………………………………………………………………....……..... 1 A ShortTerm Collaboration …………………………………………..……….… 17 On My Side ………………………………………………………….…………... 20 Aloha ………………………………………………………………….………..... 24 Sufficient unto the Day Is the Evil Thereof ……………………………..….......... 30 The Fungus Amongus ………………………………………………………......... 42 All Aboard ……………………………………………………………………....... 59 It’s What’s Inside …………………………………………………………..…....... 72 My Living Room is Dead to Me …………………………………………..…........ 76 iii 1 Carry On Soothing, persistent chimes accompanied the sudden glow of tiny pictograms above each passenger’s seat. An angular brunette wafted down the central aisle, touching sleeping men and women gently on the shoulder. Blearyeyed, they stared at her beaming face and followed her long fingers as they seamlessly wove the international gestures for seatbelt, please! Nigel had buckled himself in within milliseconds of hearing the first chime, tightening the belt an extra half inch past comfort for good measure. He grinned up at the stewardess as she swept by, making the international face for Rules, am I right? Gotta have ‘em. Love me? As always, his eagerness went willfully unnoticed. He frowned down at the hemisphere of his gut, watching it rise and fall and hang over the taut gray safety strap. Flying always made him especially constipated, but it seemed that his mother might have been right: he was getting rather rolypoly.