Moloch! Moloch! Robot Apartments!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT OF

Case 1:99-cv-02496-PLF Document 6276 Filed 08/03/18 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Plaintiff, ) Civil Action No. 99-CV-2496 (PLF) ) and ) ) CAMPAIGN FOR TOBACCO-FREE ) KIDS, et al., ) Plaintiff-Intervenors, ) ) v. ) ) PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., et al., ) Defendants. ) ) and ) ) ITG BRANDS, LLC, et al., ) Post-Judgment Parties ) Regarding Remedies ) PLAINTIFFS’ 2018 SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF ON RETAIL POINT OF SALE REMEDY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 5 I. The Deal between Cigarette Manufacturers and Retailers ............................................... 5 II. Benefits to Participating Retailers .................................................................................... 6 III. Manufacturers’ Contractual Control over Space for Cigarette Marketing and Promotional Displays ....................................................................................................... 8 A. The types of retail advertising and marketing space ........................................8 B. The manufacturers’ contractual authority over participating retailers’ space 10 1. The -

South Carolina Tobacco Directory

South Carolina Tobacco Directory Updated: June 14, 2019 Office of the Attorney General South Carolina Tobacco Directory Alan Wilson Company Name Brand Name Original Certification Date Agreement type Status Cheyenne International LLC Decade 8/10/2005 NPM Compliant Aura 6/16/2014 NPM Compliant Cheyenne 8/10/2005 NPM Compliant Commonwealth Brands, Inc. USA Gold 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Crowns 3/16/2011 PM Compliant Rave 7/15/2009 PM Compliant Rave (RYO) 7/15/2009 PM Compliant Montclair 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Fortuna 9/15/2008 PM Compliant Sonoma 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Compania Tabacalera Internacional, S.A. Director 12/27/2017 NPM Compliant Dosal Tobacco Corporation 305 8/9/2010 NPM Compliant DTC 8/9/2010 NPM Compliant Firebird Manufacturing Cherokee 8/4/2010 NPM Compliant Palmetto 8/4/2010 NPM Compliant ITG Brands LLC Kool 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Winston 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Salem 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Maverick 8/11/2005 PM Compliant Japan Tobacco International U.S.A., Inc. Wave 8/10/2005 PM Compliant LD by L. Ducat 5/6/2016 PM Compliant Export A 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Kretek International Taj Mahal Bidis 10/18/2005 PM Compliant KT&G Corporation page: 0 of 1 Carnival 2/15/2012 NPM Compliant THIS 2/15/2018 NPM Compliant Timeless Time 2/15/2012 NPM Compliant Liggett Group Inc. Pyramid 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Liggett Select 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Eve 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Bronson 10/4/2011 PM Compliant Grand Prix 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Tourney 9/8/2005 PM Compliant Tourney Slims 8/9/2005 PM Compliant NASCO Products, LLC SF 1/5/2015 PM Compliant Native Trading Associates Mohawk 8/6/2013 NPM Compliant Native 6/14/2006 NPM Compliant Native (RYO) 12/10/2007 NPM Compliant Ohserase Manufacturing Signal 8/1/2011 NPM Compliant Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Turkish Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Danish Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant London Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Amsterdam Shag (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Stockholm Blend (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Norwegian Shag (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Philip Morris USA Inc. -

Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons School of Public Policy Working Papers School of Public Policy 1-22-2019 Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California James Prieger Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sppworkingpapers Part of the Econometrics Commons, Health Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Prieger, James, "Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California" (2019). Pepperdine University, School of Public Policy Working Papers. Paper 75. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sppworkingpapers/75 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Policy at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Public Policy Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. PEPPERDINE UNIVERSITY Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California January 22, 2019 Jonathan Kulick James E. Prieger JDK Analysis Professor 30 Regent #318 Pepperdine University Jersey City, NJ 07302 School of Public Policy 24255 Pacific Coast Highway [email protected] Malibu, CA 90263-7490 James.Prieger@ pepperdine.edu School of Public Policy 24255 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, CA 90263- 7490 Abstract Illicit trade in tobacco products (ITTP) creates many harms including reduced tax revenues; damages to the economic interests of legitimate actors; funding for organized-crime and terrorist groups; negative effects of participation in illicit markets, such as violence and incarceration; and reduced effectiveness of smoking-reduction policies, leading to increased damage to health. -

Tobacco Securitization

Memorandum Office of Jenine Windeshausen Treasurer-Tax Collector To: The Board of Supervisors From: Jenine Windeshausen, Treasurer-Tax Collector Date: October 27, 2020 Subject: Tobacco Securitization Action Requested a) Adopt a resolution consenting to the issuance and sale by the California County Tobacco Securitization Agency not to exceed $67,000,000 initial principal amount of tobacco settlement bonds (Gold Country Settlement Funding Corporation) Series 2020 Bonds in one or more series and other related matters; authorizing the execution and delivery by the county of a certificate of the county; and authorizing the execution and delivery of and approval of other related documents and actions in connection therewith. b) Direct that eligible proceeds from the Series 2020 Bonds be expended on infrastructure improvements at the Placer County Government Center, construction of the Health and Human Services Building and other Board approved capital facilities projects. Background October 6, 2020 Board of Supervisors Meeting Summary. Your Board received an update regarding the County’s prior tobacco securitizations and information on the potential to refund the Series 2006 Bonds to receive additional proceeds for capital projects. Based on that update, the Board requested the Treasurer to return to the Board on October 27, 2020 with a resolution approving documents and other matters to proceed with refunding the Series 2006 Bonds. In summary from the October 6, 2020 meeting, the County receives annual payments in perpetuity from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA). The MSA payments are derived from a percentage of cigarette sales. Placer County issued bonds in 2002 and 2006 to securitize a share of its MSA payments. -

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

Pyramid Cigarettes

** Pyramid Cigarettes ** Pyramid Red Box 10 Carton Pyramid Blue Box 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Gold Box 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Silver Box 10 Carton Pyramid Orange Box 10 Carton Pyramid Red Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Blue Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Gold Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Silver Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Orange Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Non Filter Box 10 Carton ** E Cigarettes ** Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Gold 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol High 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Platinum 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Sterling 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Zero 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Gold 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette High 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Sterling 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Platinum 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Zero 24 Box ** Premium Cigars ** Acid Krush Classic Blue 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Mad Morado 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Gold 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Red 5-10pk Tin Acid Kuba Kuba 24 Box Acid Blondie 40 Box Acid C-Note 20 Box Acid Kuba Maduro 24 Box Acid 1400cc 18 Box Acid Blondie Belicoso 24 Box Acid Kuba Deluxe 10 Box Acid Cold Infusion 24 Box Ambrosia Clove Tiki 10 Box Acid Larry 10-3pk Pack Acid Deep Dish 24 Box Acid Wafe 28 Box Acid Atom Maduro 24 Box Acid Nasty 24 Box Acid Roam 10 Box Antano Dark Corojo Azarosa 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo El Martillo 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo Pesadilla 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo Poderoso 20 Box Natural Dirt 24 Box Acid Liquid 24 Box Acid Blondie -

Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Marketing Orders for New Cigarettes Marketed by Commonwealth Brands, Inc

Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Marketing Orders for New Cigarettes Marketed by Commonwealth Brands, Inc. Prepared by Center for Tobacco Products U.S. Food and Drug Administration June 26, 2019 1 Table of Contents 1. Applicant and Manufacturing Facility Information ...................................................................... 3 2. Product Information ................................................................................................................... 3 3. The Need for the Proposed Actions ............................................................................................. 4 4. Alternatives to the Proposed Actions .......................................................................................... 4 5. Potential Environmental Impacts of the Proposed Actions and Alternatives – Manufacturing the New Products .......................................................................................................................... 4 5.1. Affected Environment ......................................................................................................... 5 5.2. Air Quality ........................................................................................................................... 6 5.3. Water Resources ................................................................................................................. 6 5.4. Soil, Land Use, and Zoning .................................................................................................. 6 5.5. Biological Resources -

Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nicotine Manuscript Author Tob Res. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 July 01. Published in final edited form as: Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 July ; 18(7): 1575–1580. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv162. Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes Jiu Ai, Ph.D.1, Kenneth M. Taylor, Ph.D.1, Joseph G. Lisko, M.S.2, Hang Tran, M.S.2, Clifford H. Watson, Ph.D.2, and Matthew R. Holman, Ph.D.1 1Office of Science, Center for Tobacco Products, United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD 20993 2Tobacco Products Laboratory, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA Abstract Introduction—In 2011 menthol cigarettes accounted for 32 percent of the market in the United States, but there are few literature reports that provide measured menthol data for commercial cigarettes. To assess current menthol application levels in the U.S. cigarette market, menthol levels in cigarettes labeled or not labeled to contain menthol was determined for a variety of contemporary domestic cigarette products. Method—We measured the menthol content of 45whole cigarettes using a validated gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method (GC/MS). Results—In 23 cigarette brands labeled as menthol products, the menthol levels of the whole cigarette ranged from 2.9 to 19.6 mg/cigarette, with three products having higher levels of menthol relative to the other menthol products. The menthol levels for 22 cigarette products not labeled to contain menthol ranged from 0.002 to 0.07 mg/cigarette. -

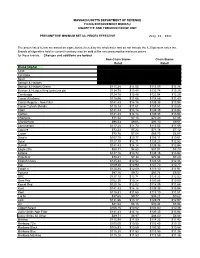

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

Forum Vormärz Forschung, Jahrbuch 2017, 23. Jahrgang

Kuratorium: Michael Ansel (Wuppertal), Olaf Briese (Berlin), Birgit Bublies-Godau (Dortmund), Norbert Otto Eke (Paderborn), Philipp Erbentraut (Frank- furt a. M.), Jürgen Fohrmann (Bonn), Bernd Füllner (Düsseldorf ), Katharina Gather (Paderborn), Katharina Grabbe (Münster), Detlev Kopp (Bielefeld), Hans-Martin Kruckis (Bielefeld), Sandra Markewitz (Vechta), Anne-Rose Meyer (Wuppertal), Maria Porrmann (Köln). Florian Vaßen (Hannover) FVF Forum Vormärz Forschung Jahrbuch 2017 23. Jahrgang Deutschland und die USA im Vor- und Nachmärz Politik – Literatur – Wissenschaft herausgegeben von Birgit Bublies-Godau und Anne Meyer-Eisenhut AISTHESIS VERLAG Das FVF im Internet: www.vormaerz.de Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Das FVF ist vom Finanzamt Bielefeld nach § 5 Abs. 1 mit Steuer-Nr. 305/0071/1500 als gemeinnützig anerkannt. Spenden sind steuerlich absetzbar. Namentlich gekennzeichnete Beiträge müssen nicht mit der Meinung der Redaktion übereinstimmen. Redaktion: Detlev Kopp © Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2018 Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 Bielefeld Satz: Germano Wallmann, geisterwort.de Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion gmbh, Wetzlar Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-8498-1298-0 www.aisthesis.de Inhalt I. Schwerpunktthema: Die USA im Vor- und Nachmärz Birgit Bublies-Godau (Bochum)/Anne Meyer-Eisenhut (Wuppertal) Verfassung, Recht, Demokratie und Freiheit. Die Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika als Modell, Ideal, Bild und Vorstellung. Einleitung ...................................................................... 11 I.1 Die Auseinandersetzung mit Amerika in Politik, Gesellschaft, Wissenschaft und Kultur und die Folgen Willi Kulke (Lage/Detmold) Aus Lippe und Westfalen nach Amerika ................................................ 65 Harald Lönnecker (Koblenz/Chemnitz) „Überall, wohin ich ging, fand ich stets auch gute alte Freunde …“. -

To Download the Oregon Product Guide

Oregon Updated on 9 - 29 - 2021 How to use index. To use the index in back of book find the proper category you want to search. Listed under each category is each book heading in alphabetical order. Find the section you wish to look under and look to the right, the format is page # - column. So if your item resides on 48-B you would find it on page 48 on the right hand column. Item # Qty. Description Pack A&S Marketing Sold To:_______________________________________________________________ Cust No.____________________ Date: ____/____/____ ------- 0001 ------- MARLBORO (PHILIP MORRIS) ------- | 016187 N AMER SPIRIT MELLOW YELLOW BOX 10 010074 N MARLBORO 83'S BOX 10 | 016193 N AMER SPIRIT MENTHOL FULL BODIED BOX 10 010139 N MARLBORO BLACK SPECIAL BLEND BX 100 10 | 016195 N AMER SPIRIT NON-FILTER BOX BROWN 10 010140 N MARLBORO BLACK SPECIAL BLEND BX KNG 10 | 016199 N AMER SPIRIT ORGANIC GOLD MELLOW BOX 10 010076 N MARLBORO BLEND #27 BOX 100 10 | 016198 N AMER SPIRIT ORGANIC TURQUOISE FB BX 10 010077 N MARLBORO BLEND #27 BOX KING 10 | 016189 N AMER SPIRIT PERIQUE BLEND BLACK BOX 10 111180 N MARLBORO BOLD ICE RESEAL PK BOX KG 10 | 017210 N AMER SPIRIT PERIQUE TOB BLND GRAYBX 10 010502 N MARLBORO BOX 100 10 | 017213 N AMER SPIRIT SKY KING MED BOX 10 010085 N MARLBORO BOX KING 10 | 016196 N AMER SPIRIT SMOOTH MELLOW ORANGE BX 10 111019 N MARLBORO EDGE BOX KING 10 | 017211 N AMER SPIRIT US GROWN FULL BODIED BX 10 010092 N MARLBORO GOLD 72'S BOX 10 | 111099 N AMER SPIRIT US GROWN MELLOW TST BX 10 010514 N MARLBORO GOLD LABEL BOX 100 10 | -------