Illicit Tobacco in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Eleventh Scientific Symposium

FLIGHT ATTENDANT MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2002-2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents................................................................................................................ 2 2013..................................................................................................................................... 4 Publications 2013............................................................................................................ 4 Presentations and Abstracts 2013 ................................................................................... 8 Book Chapters, etc., 2013............................................................................................. 11 2012................................................................................................................................... 12 Publications 2012.......................................................................................................... 12 Presentations and Abstracts 2012 ................................................................................. 34 Book Chapters, etc., 2012............................................................................................. 45 2011................................................................................................................................... 46 Publications 2011.......................................................................................................... 46 Presentations and Abstracts 2011 ................................................................................ -

Family Structure, Education and Cigarette Smoking of the Adults in China: a Double-Hurdle Model

Family Structure, Education and Cigarette Smoking of the * Adults in China: a Double-Hurdle Model Xiaohua Yu Ph.D. Candidate Agricultural, Environmental & Regional Economics and Demography Penn State University 308 Armsby Building University Park, PA 16802 Phone: +1.814.863.8248 Email: [email protected] David Abler Professor Agricultural, Environmental & Regional Economics and Demography Penn State University 207 Armsby Building University Park, PA 16802 Email: [email protected] * The first draft of this paper was presented in the seminar of the School of Finance at Renmin University of China in July 2007, and many thanks go to the seminar attendees, particularly to Professor G. Zhao of Economics of Renmin University of China, for their constructive advice. 1 Abstract : This paper suggests that cigarette smoking process can be divided into two steps: participation decision and consumption decision. Only a person decides to participate in cigarette smoking, can a positive number of cigarette consumption be observed. Following this logic, a double-hurdle statistic model is suggested for estimating the cigarette consumption, which also gives an approach to dealing with the problem of zero observations for non-smokers. Using 2004 China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), this study rejects the independence of the two decisions. The main finding is that family members can affect the participation decision of smoking but can not affect the consumption. In particular, those residing with parents, particularly with single parents, and those divorced are more likely to participate in smoking. And educational level can affect both participation decision and consumption decision, and the relation between education and cigarette addiction is more likely to be an inverted-U shape rather than a negative or positive linear relation. -

Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons School of Public Policy Working Papers School of Public Policy 1-22-2019 Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California James Prieger Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sppworkingpapers Part of the Econometrics Commons, Health Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Prieger, James, "Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California" (2019). Pepperdine University, School of Public Policy Working Papers. Paper 75. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sppworkingpapers/75 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Policy at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Public Policy Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. PEPPERDINE UNIVERSITY Empty Discarded Pack Data and the Prevalence of Illicit Trade in Cigarettes in California January 22, 2019 Jonathan Kulick James E. Prieger JDK Analysis Professor 30 Regent #318 Pepperdine University Jersey City, NJ 07302 School of Public Policy 24255 Pacific Coast Highway [email protected] Malibu, CA 90263-7490 James.Prieger@ pepperdine.edu School of Public Policy 24255 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, CA 90263- 7490 Abstract Illicit trade in tobacco products (ITTP) creates many harms including reduced tax revenues; damages to the economic interests of legitimate actors; funding for organized-crime and terrorist groups; negative effects of participation in illicit markets, such as violence and incarceration; and reduced effectiveness of smoking-reduction policies, leading to increased damage to health. -

Download Our Tobacco-Free Resource Guide for Youth

educate. engage. empower. TOBACCO-FREE COMMUNITY FORUM TOBACCO-FREE RESOURCE GUIDE for Youth, Communities, Parents, and Schools TOBACCO-FREE COMMUNITY FORUM Educate. Engage. Empower. April 28, 2021 This event made possible by the Poe Center for Health Education in partnership with Wake County Human Services, Wake County Public Schools, and the American Heart Association . TOBACCO-FREE COMMUNITY FORUM AGENDA 9:15 a.m. - 9:30 a.m. - Log-In and Sign-On Slideshow of PhotoVoice Projects 9:30 a.m. - 9:40 a.m. - Welcome & Opening Remarks Honorable Sig Hutchinson, Wake County Commissioner Ann Rollins, Executive Director, Poe Center For Health Education Roxie Cash, Wake County Board of Education 9:40 a.m. - 9:45 a.m. - Recognition of Local Champions Presented by Youth Empowerment Team 9:45 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. - A Snapshot of Tobacco’s Impact on Youth In Wake County Sumedh Kotrannavar, Student at Carnage Middle School Teja Wasudev, Student at Cary Academy Nikhil Patel, Student at Enloe High School Gorja Yadav, Student at Enloe High School Lily Zahn, Student at Fuquay-Varina High School 10:00 a.m. - 10:20 a.m. - Latest Updates on Tobacco Impacts, Trends, and Statistics Jim Martin, Director of Policy and Programs with the N.C. Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch Division of Public Health, NC Department of Health and Human Services 10:20 a.m. - 10:45 a.m. - Youth Perspective on Local Tobacco Policy Needs Panel Moderator: Honorable Sig Hutchinson, Wake County Commissioner Panelists: Sumedh Kotrannavar, Student at Carnage Middle School Teja Wasudev, Student at Cary Academy Nikhil Patel, Student at Enloe High School Lily Zahn, Student at Fuquay-Varina High School 10:45 a.m. -

Annual Report 2019 CONTENT

中煙國際 (香港) 有限公司 China Tobacco International (HK) Company Limited (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) Stock code: 6055 Annual Report 2019 CONTENT Definitions 2 Company Information 4 Financial Highlights 5 Chairman’s Statement 6 Management Discussion and Analysis 7 Review of Continuing Connected Transactions 16 Directors and Senior Management 30 Report of the Directors 37 Corporate Governance Report 48 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 2019 60 Independent Auditor’s Report 86 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 91 Statement of Financial Position 92 Statement of Changes in Equity 94 Statement of Cash Flows 95 Notes to the Financial Statements 96 Financial Summary 140 2 China Tobacco International (HK) Company Limited Definitions In this annual report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall have the meanings set forth below. “AGM” annual general meeting of the Company; “Audit Committee” the audit committee of the Board; “Board” or “Board of Directors” the board of Directors of the Company; “China” or “PRC” the People’s Republic of China; for the purpose of this report only, references to “China” or the “PRC” do not include the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Macau Special Administrative Region and Taiwan; “CNTC” China National Tobacco Corporation* (中國煙草總公司), an enterprise incorporated in the PRC and the ultimate controlling shareholder of the Company; “CNTC Group” CNTC and its subsidiaries; “Company” or “we” China Tobacco International (HK) Company Limited -

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary Technical Report June 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH TEAM ................................................................................................................... iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY PROTOCOL ........................................................................................................... 1 2.1 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 1 2.2 SAMPLE AND RECRUITMENT ................................................................................. 2 3.0 STUDY CONTENT ............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 STUDY 1: HEALTH WARNING MESSAGES ............................................................... 3 3.2 STUDY 2: CIGARETTE PACKAGING ......................................................................... 4 4.0 MEASURES...................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................... 6 4.2 QUESTIONNAIRE CONTENT ................................................................................... 6 5.0 SAMPLE INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 9 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................ -

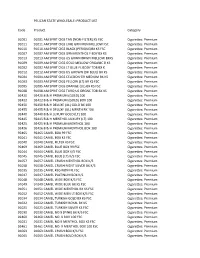

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

Supplementary Files Supplemental Table 1: Tar And

Supplementary Files Supplemental Table 1: Tar and Ventilation Levels of Chinese Cigarette Brands in 2009 and 2012 2009 2012 Tar Tar UPC Brand Name (mg) Ventilated (mg) Ventilated 6901028000642 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028000987 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028001465 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028001618 Shuang Xi 11 Yes 10 Yes 6901028002097 Cocopalm 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028002752 Cocopalm 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028011075 Jiatianxia 13 Yes 13 Yes 6901028015417 Zhenlong 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028024969 The X Catena Pride 8 Yes 8 No 6901028024990 Pride 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028025812 Pride 6 Yes 8 Yes 6901028028356 Tianxiaxiu 14 Yes 14 Yes 6901028036672 Huang Guoshu 13 Yes 13 Yes 6901028036795 Huang Guo Shu 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028037891 Huangguoshu 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028045483 Camellia 13 Yes 12 No 6901028048231 Hongtashan 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028055055 Honghe 12 Yes 13 Yes 6901028055086 Honghe 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028055208 Honghe 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028065078 Lan zhou 13 Yes 8 Yes 6901028065399 Lan zhou 13 Yes 8 Yes 6901028065580 Lan zhou 11 Yes 8 Yes 6901028071468 Zhongnanhai 5 Yes 5 Yes 6901028071499 Zhongnanhai 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028071529 Zhongnanhai 5 No 5 No 6901028071765 Zhongnanhai 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028072458 Beijing 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028072601 Zhongnanhai 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075763 Chunghwa 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075770 Chunghwa 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075831 Double Happiness 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028075992 Double Happiness 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028076333 Memphis Blue 9 Yes 9 Yes 6901028090902 Renmin Dahuitang Ben Xiang 10 No 10 Yes 6901028092944 Renmin Dahuitang 13 Yes 12 Yes -

Fire Standard Compliant Cigarette Brands & Styles

THE STATE OF UTAH Fire Standard Compliant Cigarette Brands and Styles Master Approval List List Design: First Section - Deletions to the list in the last 30 Days Second Section - Additions/Re-Certifications in the last 30 Days Third Section - Main List - Reflects Current Status Updated October 15, 2018 FIRE STANDARD COMPLIANT CIGARETTE BRANDS & STYLES MASTER APPROVAL LIST Page 1 BRANDS NOT RENEWED OR DELETED MANUFACTURER FLAVOR PACKAGE EXPIRATION DATE THIS REPORT NONE BRANDS ADDED OR RECERTIFIED THIS MANUFACTURER FLAVOR PACKAGE CERTIFICATION DATE REPORT Montego Red King Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/6/2019 Montegi Red 100's Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/5/2019 Montego Blue 100's Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/12/2019 Montego Blue Kings Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/11/2019 Montego Orange 100's Box Liggett Group Inc. Non-Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/10/2019 Montego Menthol Gold King Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/6/2019 Montego Menthol Gold 100's Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/5/2019 Montego Menthol Silver King Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/11/2019 Montego Menthol Silver 100's Liggett Group Inc. Menthol Filter Hard Pack 9/12/2019 Teton #18 Blue Kings Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 8/25/2017 Teton #18 Green Menthol Kings Wind River Tobacco., LLC Menthol Filter Hard Pack 11/30/2017 Teton #18 Yellow Kings Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 9/1/2017 Teton #18 Red 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 11/27/2017 Teton #6 Gold 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC NS Filter Hard Pack 11/28/2017 Teton #6 Green Menthol 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC Menthol Filter Hard Pack 11/29/2017 Teton #6 Black Menthol 100's Wind River Tobacco., LLC Menthol Filter Hard Pack 11/29/2017 Vantage Classic Menthol 100's Soft Pack R.J. -

Policy Statement—Tobacco Use: a Pediatric Disease Abstract

Organizational Principles to Guide and Define the Child Health Care System and/or Improve the Health of all Children Policy Statement—Tobacco Use: A Pediatric Disease COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH, COMMITTEE ON abstract SUBSTANCE ABUSE, COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE, AND COMMITTEE ON NATIVE AMERICAN CHILD HEALTH Tobacco use and secondhand tobacco-smoke (SHS) exposure are ma- jor national and international health concerns. Pediatricians and other KEY WORDS tobacco, smoke, cigarette, environmental tobacco, nicotine, clinicians who care for children are uniquely positioned to assist pa- secondhand, smoke free, cigar, smokeless tients and families with tobacco-use prevention and treatment. Under- ABBREVIATIONS standing the nature and extent of tobacco use and SHS exposure is an SHS—secondhand tobacco smoke essential first step toward the goal of eliminating tobacco use and its AAP—American Academy of Pediatrics DoD—Department of Defense consequences in the pediatric population. The next steps include coun- This document is copyrighted and is property of the American seling patients and family members to avoid SHS exposures or cease Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors tobacco use; advocacy for policies that protect children from SHS ex- have filed conflict of interest statements with the American posure; and elimination of tobacco use in the media, public places, and Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American homes. Three overarching principles of this policy can be identified: (1) Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any there is no safe way to use tobacco; (2) there is no safe level or dura- commercial involvement in the development of the content of tion of exposure to SHS; and (3) the financial and political power of this publication. -

Uk Standardised Packaging Consultation

UK STANDARDISED PACKAGING CONSULTATION RESPONSE OF BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO UK LIMITED 08 August 2012 Table of Contents Page ABOUT BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO UK LIMITED .............................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................2 1. QUESTION 1 ................................................................................................................. 10 1.1 Plain Packaging would not work and would have serious unintended consequences .................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Smoking prevalence is reducing without the need for risky additional measures ........................................................................................................... 11 1.3 The FCTC does not require Plain Packaging ..................................................... 11 1.4 Effective alternative measures ........................................................................... 12 2. QUESTION 2 ................................................................................................................. 15 3. QUESTION 3 ................................................................................................................. 16 3.1 The studies relied on in the PHRC Review are flawed and irrelevant ................. 17 3.2 Plain Packaging would not discourage young people from taking up smoking ... 20 3.3 Plain Packaging would not increase -

Download Full Curriculum Vitae

Pollay CV (Feb 2013)...1 of 45 Sauder School of Business THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 2053 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 CURRICULUM VITAE (as of February 2013) RICHARD W. POLLAY Home Address Professor Emeritus, Marketing Division 4506 West 8th Avenue Curator, History of Advertising Archives Vancouver, BC V6R 2A5 (604) 224-7322 Office Phone: (604) 822-8338 e-mail: [email protected] I. BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Place of Birth: New Britain, CT (USA) Sex: Male Date of Birth: June 28, 1940 Marital Status: Married Citizenship: Canadian & US Children: None II. EDUCATION a) Undergraduate 1958-1962: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, B. Management Engineering b) Graduate 1962-1963: University of Chicago, Masters of Business Administration 1964-1966: University of Chicago, Ph.D. (awarded, 1970) c) Graduate Theses Titles Ph.D.: "A Theoretical and Experimental Investigation into the Factors Affecting Decision Completion Time" d) Academic Awards Prior to Final Degree Ford Foundation Research Fellowship, Summer 1968 Sears and Roebuck Doctoral Fellowship, 1965 American Marketing Association, Certificate of Merit, 1962 Degree cum laude, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1962 Tau Beta Pi (Engineering Honorary) Epsilon Delta Sigma (Business Honorary) III. PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT RECORD a) Teaching or Research Positions Held Prior to UBC Appointment 1966-1970: Assistant Professor, University of Kansas b) Date of First UBC Appointment: July 1, 1970 Pollay CV (Feb 2013)...2 of 45 c) Rank of First Appointment: Associate Professor d) Subsequent Ranks