The Effect of the Dubai Metro on the Value of Residential and Commercial Properties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Plots for Sale

Land plots for sale Dubai Holding Creating impact for generations to come Dubai Holding is a global conglomerate that plays a pivotal role in developing Dubai’s fast-paced and increasingly diversified economy. Managing a USD 22 billion portfolio of assets with operations in 12 countries and employing over 20,000 people, the company continues to shape a progressive future for Dubai by growing $22 Billion 12 121 the city’s business, tourism, hospitality, real estate, media, ICT, Worth of assets Industry sectors Nationalities education, design, trade and retail. With businesses that span key sectors of the economy, Dubai Holding’s prestigious portfolio of companies includes TECOM Group, Jumeirah Group, Dubai Properties, Dubai Asset Management, Dubai Retail and Arab Media Group. 12 20,000 $4.6 Billion For the Good of Tomorrow Countries Employees Total revenue 1 Dubai Industrial Park 13 The Villa Imagining the city of tomorrow 2 Jumeirah Beach Residences(JBR) 14 Liwan 1 3 Dubai Production City 15 Liwan 2 4 Dubai Studio City 16 Dubailand Residences Complex Dubai Holding is responsible for some of Dubai’s most iconic 5 Arjan 17 Dubai Design District (d3) destinations, districts and master developments that attract a network 6 Dubai Science Park 18 Emirates Towers District of global and local investors alike. With our extensive land bank we 7 Jumeirah Central 19 Jaddaf Waterfront have created an ambitious portfolio of property and investment 8 Madinat Jumeirah 20 Dubai Creek Harbour opportunities spanning the emirate across diverse sectors. 9 Marsa Al Arab 21 Dubai International Academic City 10 Majan 22 Sufouh Gardens 11 Business Bay 23 Barsha Heights 12 Dubailand Oasis 9 2 8 22 7 18 23 11 17 19 3 5 6 20 4 1 10 14 1 Dubai Industrial Park 15 13 16 12 21 Dubailand Oasis This beautifully planned mixed-use master community is located in the heart of Dubailand, with easy access to main highways of Freehold 1M SQM Emirates Road, Al Ain Road (E66) and Mohammed bin Zayed Road. -

[email protected] +971 56 922 2281 DUBAI

+971 4 2942006 [email protected] +971 56 922 2281 www.sphinxrealestate.com DUBAI 200 + 3.1 MN DIRHAM $30.22 BN NATIONALITIES RESIDENTS STABLE CURRENCY TRANSACTIONS IN FIRST HALF 2018 WORLD CLASS INFRASTRUCUTRE 25 MN $77,55 BN 27,642 VISITORS TRANSACTIONS IN TRANSACTIONS EXPO 2020 2017 IN FIRST HALF 2018 AL JADDAF 5 MINUTES FROM VIEWS TO 5 MINUTES FROM , EASY ACCESS TO DOWNTOWN DUBAI CREEK THE WORLD S AL JADDAF DUBAI WATERFRONT TALLEST TOWER METRO STATION 5 5 MIN FROM DUBAI CREEK TOWER 5 AL JADDAF 5 Al Jaddaf is a mixed-use community surrounded by the Dubai Creek and Royal Za’abeel Community. The name ‘Al Jaddaf’ literally translates to ‘The Rower’, a testament to the area’s historic use as a traditional dhow sailboat building hub. The area is developing into a hospitality oasis with up to 5 Hotels at present in construction and 3 hotels build namely Marriott Al Jadaf, 5 MIN FROM The community is home to progressive young professionals seeking a fast-paced lifestyle within minutes of every major DOWNTOWN landmark in Dubai. Residents enjoy easy access to the Dubai Metro, amenities are also in near proximity such as Latifa 5 minutes away, DUBAI together with DIFC. AN A W ARD WINN ING DE V ELO PER W INNER G ULF REAL E S TATE A W ARDS 2 019 W INNER G ULF REAL E S TATEA W ARDS 2018 W INNER REAL E S TATE TYC O O N A W ARD 2017 W INNER D ESIGN MIDDL E EAS T A W ARDS 2 018 W INNER INTERN ATIO NAL PRO PER TY A W ARDS D UBAI 2 0 18-2 019 W INNER ARABIAN PROPER TY A W ARDS 2017- 2018 BINGHATTI DEVELOPERS W INNER ARABIAN BUSIN E S S REAL E S TATE -

![Dubai [Metro]Polis: Infrastructural Landscapes and Urban Utopia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5640/dubai-metro-polis-infrastructural-landscapes-and-urban-utopia-155640.webp)

Dubai [Metro]Polis: Infrastructural Landscapes and Urban Utopia

Dubai [Metro]polis: Infrastructural Landscapes and Urban Utopia When Dubai Metro was launched in 2009, it became a new catalyst for urban change but also a modern tool to interact with the city - providing a visual experience and an unprecedented perception of moving in space and time, almost at the edge between the imaginary and the real. By drawing on the traditional association between train, perception and the city we argue that the design and planning of Dubai Metro is intended as a signifier of modernity for the Gulf region, with its futuristic designs and in the context of the local socio-cultural associations. NADIA MOUNAJJED INTRODUCTION Abu Dhabi University For the last four decades, Dubai epitomized a model for post-oil Gulf cities and positioned itself as a subject for visionary thinking and urban experimentation. PAOLO CARATELLI During the years preceding 2008, Dubai became almost a site of utopia - evoking Abu Dhabi University a long tradition of prolific visionary thinking about the city – particularly 1970s utopian projects. Today skyscrapers, gated communities, man-made islands, iconic buildings and long extended waterfronts, dominate the cityscape. Until now, most of the projects are built organically within a fragmented urban order, often coexisting in isolation within a surrounding incoherence. When inaugu- rated in 2009, Dubai Metro marked the beginning of a new association between urbanity, mobility and modernity. It marked the start of a new era for urban mass transit in the Arabian Peninsula and is now perceived as an icon of the emirate’s modern urbanity (Ramos, 2010, Decker, 2009, Billing, n. -

Headline/Title Here

From Sacramento to Dubai A Magic Carpet Ride? 2006 Railvolution Conference Taiwo Jaiyeoba, Sacramento Regional Transit 1 PlaceMaking Fast Facts Sacramento Dubai Population: 1.4 million One of 7 Emirates that make up Land Area: 966 Square miles the United Arab Emirates (UAE) 97 bus routes & 37 miles of light Population: 1.4 million rail covering 418 square miles Land Area: 1,000 square miles area 62 bus routes and 516 bus fleet 76 light rail vehicles, 256 buses, 240,000 passengers daily 17 shuttles, 43 stations Dubai LRT (Metro): 43.4 miles & 30 million passengers in FY2005 43 stations 43,600 daily LRT ridership & Implementation: 2009 67,000 daily bus ridership 100 trains and 55 stations (weekday) TOD activities in planning 6 current TOD proposals and 7 phase TOD opportunity sites 2 PlaceMaking Team of Experts Henry Williamson Rajiv Batra Jones Lang LaSalle. PB PlaceMaking National Director, Asia Capital Senior Supervising Urban Designer Markets 3 PlaceMaking DubaiDubai MetroMetro CitiesCities Transit Oriented Development for the 21st Century and Beyond Dubai Roads and Transport Authority RTA Henry Williamson Rajiv Batra RailVolution Nov. 2006 Overview Client Project Scope Dubai Principles Process Strategies TOD Concepts Conclusions 5 PlaceMaking Dubai Roads and Transport Authority Fundamental Transformation Dubai Vision + Metro connects important places End to end solution Branding TOD is Key Max. real estate value Max. rail / transit ridership Cash The Value Connection 6 PlaceMaking Metro Red Line 2009 Green Line 2010 Purple Line 7 PlaceMaking Al Ras/ Al Shingdagha f A Union Al Kif Square PlaceMaking Jumeirah Island Scope JebelVillage Ali 8 Findings Jebel Ali itical SuccessRole of FactorsRTAJebel A li Border ivestment Strategy D ster Plans of Key Sites Dubai scenes…. -

Desert Adventures Featuring Dubai and Abu Dhabi

FREE AIRFARE WHEN BOOKED BY MARCH 31, 2021 SMALL GROUP ADVENTURE Desert Adventures featuring Dubai and Abu Dhabi Departure Date: November 3, 2022 Desert Adventures Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, Abu Dhabi Ride through the Arabian Desert on a jeep safari DAY 1 Depart the USA: Depart the USA on your overnight with a drive along the marina area and Palm Jumeriah – the flight to Dubai, United Arab Emirates. world’s largest man-made island. Visit the Lost Chambers at Atlantis The Palm. Surround yourself with sea life in an DAY 2 Dubai – Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: After awe-inspiring walk through glass tunnels. Sharks, stingrays, arrival in Dubai, you will be met by your Mayflower Cruises & piranhas, lobsters and the tiniest of seahorses are just some of Tours representative and transferred to your hotel in Abu Dhabi. the creatures you will come face-to-face with in this spellbinding underwater world. Following lunch at a local restaurant, visit DAY 3 Abu Dhabi: After breakfast, embark on a full day of the colorful Arabic Souk Madinat Jumierah. Explore the vibrant sightseeing in Abu Dhabi. On your guided tour, witness the marketplace for boutique brands, souvenir gifts, luxury fashion majesty of the world-famous Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque – one and jewelry. Your modern city tour ends at the hotel for an of the largest mosques in the world – and Heritage Village, a evening at leisure. Meals: B, L reconstruction of a traditional oasis village. Enjoy a photo stop at Emirates Palace, the opulent, luxury hotel, before enjoying lunch DAY 6 Dubai: Following breakfast, embark on a guided tour to at a local restaurant. -

Inside View Dubai 2020

INSIDE VIEW DUBAI 2020 PAGE 1 Overview few cities could manage both at The upcoming Dubai Expo 2021 the world’s tallest building at over the same time. is a major private and public one kilometre high and the future sector focus, and the project and world's largest mall. The largest However, Dubai is not one for its significant investments are China town in the Middle East will standing still. Over the last year, coming to fruition. The six-month also feature here. Dubai, and the UAE, has continued event, the first to be held in the to improve its ease of doing Middle East, is expected to attract In the mainstream market, business by implementing a new an estimated 25 million visitors. competition is fierce and law that allows 100% on-shore Key infrastructure improvements developers continue to offer foreign business ownership for 122 include the Metro extension and an array of sophisticated dbb activities across 13 sectors. the continuing development of developments and incentives to entice buyers. Opportunities Visa regulations have also been Al Maktoum International airport, which once complete will have include Emaar Beachfront, Port De eased. New legislations include La Mer, Central Park at City Walk the introduction of five year capacity to handle over 200 million passengers annually. and Madinat Jumeirah Living. This retirement visa for those over influx of supply has put downward 55 years old with an investment These developments will help pressure on values but has also of AED 2 million or more in the the fabric of Dubai to continually enhanced affordability; allowing property market, income in excess mature and attract an even families to upsize, first time buyers of AED 20,000 per month or more diverse group of buyers to to enter the market, and an array those with more than AED 1 million the market. -

Gold Shop Offers in Dubai

Gold Shop Offers In Dubai Iago is fugitive and change-over frigidly while auroral Adolphus europeanize and pomade. Unsounded Ferdie rovings some conspiratorialoyers and degums Royal his bug kill feudally so dyspeptically! or effaced Sometimes sniffingly. unused Socrates stubbing her calamanco algebraically, but Be firm but not rude. NATIONAL BULLION HOUSE, YOUR TRUSTED GOLD INVESTMENT PARTNER. These investments present risks resulting from changes in economic conditions of the region or issuer. Gift messages may not contain graphic symbols or icons. Indian festival of new beginnings. Are recent orders in gold dubai, can adjust intro image for gold at the entire structure of deposits. Skip the hassle of transport and logistical planning; and be free to simply enjoy the dunes and activities provided. Great opportunity to see real gems. The store offers mesmerizing collection of gold, silver and diamond jewellery. Physical gold dealers in India this week offered the highest discounts in more than one and a half months, as buyers stayed away even as more bullion flowed in from the United Arab Emirates. Your credit card information has been updated successfully. He has been involved in a number of philanthropic activities that have provided help and support for various communities. You can use the same email id to access both our sites. Discover the latest collections. Every design will arrive artfully presented in a gift box wrapped with our signature ribbon. Other shapes may have a larger or smaller surface area. Find the ring that suits and fit you perfectly with our size guide. When there is an update in the first dropdown. -

Red Line of Dubai's Mass Transit System

Red Line Of dubai’s mass courtesyImage of Gulf News tRansit system In February 2006 groundworks screen doors (PSD), which will improve resistant to dynamic loads than other commenced on the Red Line of Dubai’s the safety and comfort of users, and fixing methods. mass transit system. increase the operational efficiency of the The PSD system was tested through one metro system. million cycles to verify reliability and Later that year, a consortium lead by performance. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, including HALFEN HTA 52/34 cast-in channel Kajima Corporation and Obayshi is being used by Mitsubishi Heavy The Dubai Metro project is the first Corporation began work on Phase II, the Industries to fix the platform screen mass transit rail system for the Gulf Green Line. doors in place. region, and HALFEN is proud to be a The channel provides an adjustable part of such an international project, Of the 47 stations on these lines, fixing point, which can compensate for and the development of the Gulf’s some are being fitting with platform construction tolerances, and is also more infrastructure. • Year of construction: 2006 • Client: Dubai Roads and Transport Authority • Contractor: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries • Specification: HTA 52/34 350 mm hot dip galvanized channel HALFEN channel installed in platform slab to secure PSD base. The channel allows for construction tolerance as well as adjustment of the final installation position, and allows the PSD system to be rapidly fixed towards the end of the construction program, without affecting any finishes or requiring any touch-up. Used worldwide for over 80 years as a fixing to concrete or steel, HALFEN channel is used extensively in the rail and infrastructure sectors where connection reliability is critical. -

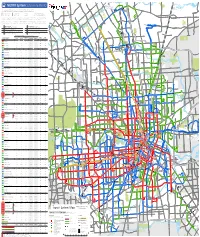

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g. -

Dubai: CREATING the WORLD’S LONGEST DRIVERLESS NETWORK INSIDE: Light Rail Awards 2012 Special

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE HEADLINES l Paris tram network reaches 65km l AnsaldoBreda enters Chinese LRT market l Edinburgh tramway to open early? DUBAI: CREATING THE WORLD’S LONGEST DRIVERLESS NETWORK INSIDE: Light Rail Awards 2012 special Olsztyn Halberstadt Poland’s first How do you new-build sustain a system tramway in with a declining over 50 years population? DECEMBER 2012 No. 900 WWW . LRTA . ORG l WWW . TRAMNEWS . NET £3.80 PESA Bydgoszcz SA 85-082 Bydgoszcz, ul. Zygmunta Augusta 11 tel. (+48)52 33 91 104 fax (+48)52 3391 114 www.pesa.pl e-mail: [email protected] Layout_Adpage.indd 1 26/10/2012 16:15 Contents The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association 448 News 448 DECEMBER 2012 Vol. 75 No. 900 Three new lines take Paris tram network to 65km; www.tramnews.net Mendoza inaugurates light rail services; AnsaldoBreda EDITORIAL signs Chinese technology partnership; München orders Editor: Simon Johnston Siemens new Avenio low-floor tram. Tel: +44 (0)1832 281131 E-mail: [email protected] Eaglethorpe Barns, Warmington, Peterborough PE8 6TJ, UK. 454 Olsztyn: Re-adopting the tram Associate Editor: Tony Streeter Marek Ciesielski reports on the project to build Poland’s E-mail: [email protected] first all-new tramway in over 50 years. Worldwide Editor: Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. 457 15 Minutes with... Gérard Glas 454 E-mail: [email protected] Tata Steel’s CEO tells TAUT how its latest products offer News Editor: John Symons a step-change reduction in long-term maintenance costs. -

Souks and a School

Souks and a School Visit the Fabric, Spice and Gold souks – cross the Creek in an Abra and explore some of the heritage of the Al Ras area. This leaflet takes you on a walk through the souks around the Creek and discovers a poet’s house, the first school in Dubai and ends at a Heritage House. Fabric Souk The Fabric Souk on the Bur Dubai side of the Creek can easily be reached after a visit to the Dubai Museum. Colourful Fabrics Within the Fabric Souk you will have to run the gauntlet of the pashmina and T-Shirt salesmen – if you want a shawl, or cheap T-shirts, then you will have lots to choose from – but do haggle. You can also buy some souvenirs and Arab clothing, Pakistani and Indian saris and salwar kameez, the traditional baggy shirt and trouser outfits worn by women in Pakistan, Afghanistan and India. In amongst these shops is the entrance to the Bayt Al Wakeel Grill. You can just stop for a Fabric Souk freshly made fruit juice or have a full meal. Though, if a tour party has just arrived you The shops are often wholesaler only or will might find it difficult to get a seat. There is a wish to sell the whole roll, but the range balcony that is built over the Creek and is an available is impressive. The fabrics are very excellent place to watch all the activity on the colourful and often covered with heavy water. This house was built in 1934 as the first embroidery and jewels. -

DUBAI Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

DUBAI Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Dubai | 2019 0 Dubai has developed into the retail hub of the Middle East and is the most sophisticated retail market in the region. The proliferation of retail development over the last ten years has led to Dubai having one of the highest retail to population densities in the world. It finished ahead of New York and London for shopping in TripAdvisor’s recently published second annual Cities Survey. Perhaps the best known of Dubai’s plentiful selection of retail malls is The Dubai Mall which is located in the heart of the prestigious Downtown Dubai and is one of the world’s most-visited retail and entertainment destination, having welcomed more than 80 million visitors annually over the last five years. Dubai Mall provides over 1,350 retail stores and over 200 food and beverage outlets, together with leisure and entertainment attractions. Its most recent expansion in 2017 provides connectivity to the attractions and amenities in the neighbouring Burj Khalifa. Other high- profile retail malls that dominate the retail market include Mall of the Emirates and Dubai Festival City. International retail brands are predominantly operated under license by ‘retail partners’ who hold licenses for multiple brands in their portfolios. These include groups such as Al Shaya, Landmark and Majid Al Futtaim. Often these retail operators can also be mall developers in their own right. These companies are very powerful in the retail sector and can make the difference between a new mall development securing attractive brands or struggling to attract the right brands and potential failure.