Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Music :A Comprehensive Ilbrar

1wmm H?mi BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT or Hetirg W, Sage 1891 A36:66^a, ' ?>/m7^7 9306 Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V.9 The art of music :a comprehensive ilbrar 3 1924 022 385 342 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385342 THE ART OF MUSIC The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia UniveTsity Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modem Music Society of New Yoric In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Lillian Nordica as Briinnhilde After a pholo from life THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME NINE The Opera Department Editor: CESAR SAERCHINGER Secretary Modern Music Society of New York Author, 'The Opera Since Wagner,' etc. Introduction by ALFRED HERTZ Conductor San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Formerly Conductor Metropolitan Opera House, New York NEW YORK THE NASTIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC i\.3(ft(fliji Copyright, 1918. by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Bights Reserved] THE OPERA INTRODUCTION The opera is a problem—a problem to the composer • and to the audience. The composer's problem has been in the course of solution for over three centuries and the problem of the audience is fresh with every per- formance. -

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(S): Frederick Niecks Source: the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(s): Frederick Niecks Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 42, No. 696 (Feb. 1, 1901), pp. 96-97 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3366388 . Accessed: 21/12/2014 00:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 00:58:46 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions L - g6 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, I901. of any service is, of course, always undesirable. musical society as well as choir inspectorand con- But it is permissible to remind our young and ductor to the Church Choral Association for the enthusiastic present-day cathedral organists that the Archdeaconryof Coventry. In I898 he became rich store of music left to us by our old English church organistand masterof the choristersof Canterbury composers should not be passed by, even on Festival Cathedral,in succession to Dr. -

Mannheim Le 12 Nov:Bre Mon Trés Cher Pére!2 1778 I Arrived Here Well

0504.1 MOZART TO HIS FATHER, SALZBURG Mannheim le 12 Nov:bre Mon Trés cher Pére!2 1778 I arrived here well on the 6th and surprised all my good friends in a pleasant way; – praise and thanks be to God that I am once again in my beloved Mannheim! [5] I assure you that you would say the same if you were here; I am lodging with Mad:me Cannabich3 – who, along with her family and all good friends, was almost beside herself for joy when she saw me again; – we have not finished talking yet, for she is telling me all the stories and changes that have happened my absence; – [10] I have not yet eaten at home the whole time I have been here – for it is full-blooded, this fighting over me; in a word; as I love Mannheim, Mannheim loves me; – And I do not know for sure, I believe I will yet in the end be taken on4 here! – here, not in Munich; for the Elector5 would, I believe, <be very glad to have his residence in Manheim again>, [15] since he will not possibly be able <to put up> with the <crudities> of the <Bavarian gentlemen> for long! – You know that the Mannheim troupe6 is in Munich? – there they have already whistled the 2 leading actresses, Mad:me Toscani7 and Mad:me Urban,8 off the stage, and there was so much noise that <the Elector himself> leaned out of his <box> and said sh– – [20] but after no-one allowed themselves to be put off by that, he sent someone down, – but <Count Seau9>, after he said to some officers they should not make so much noise, <the Elector> didn’t like to see it, received this answer; – <it was with their good money that they got in> there and <they are not taking orders from anyone> – yet what a fool I am! [25] You will long since have heard this from our – ;10 Now here comes something; – perhaps I can earn 40 louis d’or11 here! – Admittedly I must stay here 6 weeks – or 2 months at the most; – Seiler’s troupe12 is here – who will already be known to you by renomè;13 – Herr von Dallberg14 is their director; – this man 1 This letter contains passages in "family code"; these are marked with angle brackets < >. -

Mozart and the Young Beethoven

MOZART AND THE YOUNG BEETHOVEN By GEORGES DE ST. FOIX ^M/[AY it be permittedto me as an explorerof the wide reaches of the Land of Mozart to cast an inquiring glance over the edge of the great forest of the domain of Beethoven where it touches (perhaps I should say where it runs over into) the regions which have become familiar to me. For there is a whole period, a very important and, one might say, an almost unknown period of Beethoven's youth in which every work bears some re- lation to Mozart. Both composers use the same language, even if the proportions are not the same. The stamp of Mozart is discernible in all the works of the young dreamer of Bonn, though under all exterior resemblances we may observe a certain brusque- ness mitigated only by self-restraint, a certain already concentra- ted passion, and furthermore a tinge of thoroughly pianistic virtuosity, which manifests itself at times even in the parts en- trusted to other instruments. It is not without a measure of respectful awe that I venture to-day to study the growth, or rather one of the stages in the growth of a master who will always, through all the changes and chances of time, be numbered among the greatest of men, not only for the sake of his works, but, in my humble opinion, for the profoundly human spirit which dwelt in his heart. It must be freely confessed that the period in question, so important, decisive even, for the artistic growth of Beethoven, is wholly unknown. -

Sachgebiete Im Überblick 513

Sachgebiete im Überblick 513 Sachgebiete im Überblick Dramatik (bei Verweis-Stichwörtern steht in Klammern der Grund artikel) Allgemelnes: Aristotel. Dramatik(ep. Theater)· Comedia · Comedie · Commedia · Drama · Dramaturgie · Furcht Lyrik und Mitleid · Komödie · Libretto · Lustspiel · Pantragis mus · Schauspiel · Tetralogie · Tragik · Tragikomödie · Allgemein: Bilderlyrik · Gedankenlyrik · Gassenhauer· Tragödie · Trauerspiel · Trilogie · Verfremdung · Ver Gedicht · Genres objectifs · Hymne · Ideenballade · fremdungseffekt Kunstballade· Lied· Lyrik· Lyrisches Ich· Ode· Poem · Innere und äußere Strukturelemente: Akt · Anagnorisis Protestsong · Refrain · Rhapsodie · Rollenlyrik · Schlager · Aufzug · Botenbericht · Deus ex machina · Dreiakter · Formale Aspekte: Bildreihengedicht · Briefgedicht · Car Drei Einheiten · Dumb show · Einakter · Epitasis · Erre men figuratum (Figurengedicht) ·Cento· Chiffregedicht· gendes Moment · Exposition · Fallhöhe · Fünfakter · Göt• Echogedicht· Elegie · Figur(en)gedicht · Glosa · Klingge terapparat · Hamartia · Handlung · Hybris · Intrige · dicht . Lautgedicht . Sonett · Spaltverse · Vers rapportes . Kanevas · Katastasis · Katastrophe · Katharsis · Konflikt Wechselgesang · Krisis · Massenszenen · Nachspiel · Perioche · Peripetie Inhaltliche Aspekte: Bardendichtung · Barditus · Bildge · Plot · Protasis · Retardierendes Moment · Reyen · Spiel dicht · Butzenscheibenlyrik · Dinggedicht · Elegie · im Spiel · Ständeklausel · Szenarium · Szene · Teichosko Gemäldegedicht · Naturlyrik · Palinodie · Panegyrikus -

Musikalische Belustigungen

MUSIKALISCHE BELUSTIGUNGEN ____________________ KATALOG NR. 473 Inhaltsverzeichnis Nr. 1-388 Musicalia Nr. 389-537 Kammermusik Nr. 538-609 Klaviermusik MUSIKANTIQUARIAT HANS SCHNEIDER D 82327 TUTZING Es gelten die gesetzlichen Regelungen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Alle Angebote sind freibleibend. Preise einschließlich Mehrwertsteuer in Euro (€). Meine Rechnungen sind nach Erhalt ohne Abzug zahlbar. Falls Zahlungen nicht in Euro lauten, bitte ich, die Bankspesen in Höhe von € 15.– dem Rechnungsbetrag hinzuzufügen. Versandkosten zu Lasten des Empfängers. Begründete Reklamationen bitte ich innerhalb von 8 Tagen nach Empfang der Ware geltend zu machen. (Keine Ersatzleistungspflicht). Gerichtsstand und Erfüllungsort für beide Teile Sitz der Lieferfirma. Eigentumsvorbehalt gemäß § 455 BGB. Die angebotenen Werke befinden sich in gutem Erhaltungszustand, soweit nicht anders vermerkt. Unwesentliche Mängel (z. B. Namenseintrag) sind nicht immer angezeigt, sondern durch Preisherabsetzung berücksichtigt. Über bereits verkaufte, nicht mehr lieferbare Titel erfolgt keine separate Benachrichtigung. Mit der Aufgabe einer Bestellung werden meine Lieferbedingungen anerkannt. Format der Bücher, soweit nicht anders angegeben, 8°, das der Noten fol., Einband, falls nicht vermerkt, kartoniert oder broschiert. ABKÜRZUNGEN: S. = Seiten Pp. = Pappband Bl. (Bll.) = Blatt Kart. = Kartoniert Aufl. = Auflage Brosch. = Broschiert Bd. (Bde.) = Band (Bände) d. Zt. = der Zeit Diss. = Dissertation besch. = beschädigt PN = Platten-Nummer verm. = vermehrt VN = Verlags-Nummer hg. = herausgegeben Abb. = Abbildung bearb. = bearbeitet Taf. = Tafel Lpz. = Leipzig Ungeb. = Ungebunden Mchn. = München o. U. = ohne Umschlag Stgt. = Stuttgart O = Originaleinband Bln. = Berlin des Verlegers Ffm. = Frankfurt/Main Pgt. (Hpgt.) = (Halb-)Pergament o. O. = ohne Verlagsort Ldr. (Hldr.) = (Halb-)Leder o. V. = ohne Verlagsangabe Ln. (Hln.) = (Halb-)Leinen BD = Bibliotheksdublette Köchel6 = Köchel 6. Aufl. Sdr. = Sonderdruck Eigh. = Eigenhändig B&B = Bote & Bock m. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

ISBN: 9780143126065 Author: Paul Johnson Mozart A

ISBN: 9780143126065 Author: Paul Johnson Mozart A Life Excerpt Chapter Four MOZART’S OPERATIC MAGIC There are many extraordinary things about Mozart, but the most extraordinary thing of all is his work in opera. There was nothing in his background to prepare him for the stage. His father knew everything about the violin and was familiar with every aspect of church music, but opera was foreign territory to him. It is true that during their three visits to Italy, they had the opportunity to see opera, and Mozart (not his father) successfully absorbed various forms of Italian musical idiom. But until he began to grow up, Mozart rarely went to the theater, especially the opera. He seems to have acquired the instinct to make music dramatic, to animate people on stage, entirely from his own personality. Yet his impact on the form was fundamental. He found opera, so called, in rudimentary shape and transformed it into a great, many-faceted art. He is the first composer of operas who has never been out of the repertoire, but is an indispensable part of it, a central fact in the history of opera. He forms, along with Verdi and Wagner, the great tripod on which the genus of opera rests, but whereas they devoted their lives to the business, opera is for Mozart only one part of his musical career; not necessarily the most important part, either. Mozart composed twenty operas, by one computation, twenty-two by another. Opera was evolving fast in the eighteenth century, and definition is difficult. To begin with, it was composed in four main languages, Italian, French, German, and English. -

Concert Reviews (2011–2017) from 2011 Through 2017 I Occasionally Reviewed Concerts for the Online Boston Musical Intelligence

Concert Reviews (2011–2017) From 2011 through 2017 I occasionally reviewed concerts for the online Boston Musical Intelligencer, imagining that by offering commentary on local performances I might provide information about the music for listeners and helpful suggestions for performers and presenters. But of course this was quixotic, not to say presumptuous, and on the rare occasions when my reviews solicited comments these were usually to complain about their length, or about my criticisms of anachronistic performance practices and inaccurate claims in program notes. I discovered, too, that as a performer myself, and one who knew and has worked with and even taught some of those I found myself reviewing, it could be difficult to preserve my objectivity or to avoid offending people. An additional frustration was that many of my reviews appeared with editorial changes that introduced not only grammatical errors and misspellings but sometimes misstatements of fact, even altering the views I had expressed. I know that few things are as stale as old reviews, but for the record I include below all these reviews as I wrote them, arranged by date of publication from the most recent to the earliest. At some point I learned that it was preferable to invent a cute-sounding headline than to have one foisted on my review, and where I did this I’ve placed it within quotation marks in the heading or on a separate line (followed by my byline). A few of these reviews are accompanied by photos that I took, although the only one of these that ran originally was that of the Resistance protest in Copley Square in January 2017. -

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Advisory Board Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska, Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Published within the Project HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area) – JRP (Joint Research Programme) Music Migrations in the Early Modern Age: The Meeting of the European East, West, and South (MusMig) Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska, Eds. Warsaw 2016 Liber Pro Arte English Language Editor Shane McMahon Cover and Layout Design Wojciech Markiewicz Typesetting Katarzyna Płońska Studio Perfectsoft ISBN 978-83-65631-06-0 Copyright by Liber Pro Arte Editor Liber Pro Arte ul. Długa 26/28 00-950 Warsaw CONTENTS Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska Preface 7 Reinhard Strohm The Wanderings of Music through Space and Time 17 Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Eighteenth-Century Warsaw: Periphery, Keystone, (and) Centre of European Musical Culture 33 Harry White ‘Attending His Majesty’s State in Ireland’: English, German and Italian Musicians in Dublin, 1700–1762 53 Berthold Over Düsseldorf – Zweibrücken – Munich. Musicians’ Migrations in the Wittelsbach Dynasty 65 Gesa zur Nieden Music and the Establishment of French Huguenots in Northern Germany during the Eighteenth Century 87 Szymon Paczkowski Christoph August von Wackerbarth (1662–1734) and His ‘Cammer-Musique’ 109 Vjera Katalinić Giovanni Giornovichi / Ivan Jarnović in Stockholm: A Centre or a Periphery? 127 Katarina Trček Marušič Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Migration Flows in the Territory of Today’s Slovenia 139 Maja Milošević From the Periphery to the Centre and Back: The Case of Giuseppe Raffaelli (1767–1843) from Hvar 151 Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska Music Repertory in the Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania. -

Mozart's Compositional Processes and Creative Complexity

David P. Schroeder Mozart's Compositional Processes and Creative Complexity Various of the nineteenth-century myths about Mozart have been slow to die. Some of the more spectacular ones, such as the alleged "involve ment" of Salieri in Mozart's death, the "mysterious" circumstances surrounding the commission for the Requiem, and the notion of Mozart as a frivolous rake who happened to be a genius, have been kept alive in recent literary, theatrical or cinematic representations. There are other myths as well, concerning his compositional processes, which have left us with a thoroughly distorted impression of the composer. Foremost among these is the assertion that composition was completely effortless for Mozart, that he could simply write down fully conceived works. His life was short, a mere thirty-five years, but in that time he produced a prodigious number of works. In the minds of some, he was more of a clairvoyant than a craftsman, happily transmitting perfect creations sent to him from another world. With respect to the notion that composition came easy for Mozart, the evidence points to something quite different. In the first instance, it should be noted that at the time of his death Mozart left a large number of fragments or unfinished works, well over 150 in fact (Wolff 191), not because he ran out of time as he did with the Requiem, but because he simply abandoned the projects, not knowing how to proceed or how to draw to a conclusion. Some of these fragments are only a few bars long, while others are hundreds of bars, and they reveal no consistent manner in breaking off. -

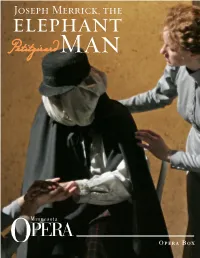

Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man Opera Box Lesson Plan Unit Overview with Related Academic Standards

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis . .22 Laurent Petitgirard – a biography ............................25 Background Notes . .27 History of Opera ........................................31 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .42 The Standard Repertory ...................................46 Elements of Opera .......................................47 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................51 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................57 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .60 Acknowledgements . .62 GIACOMO PUCCINI NOVEMBER 5 – 13, 2005 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART MARCH 4 – 12, 2006 mnopera.org SAVERIO MERCADANTE APRIL 8 – 15, 2006 LAURENT PETITGIRARD MAY 13 – 21, 2006 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. In addition, you are encouraged to include any original lesson plans.