Concert Reviews (2011–2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Early Music Festival Announces 2013 Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 1, 2012 CONTACT: Kathleen Fay, Executive Director | Boston Early Music Festival 161 First Street, Suite 202 | Cambridge, MA 02142 617-661-1812 | [email protected] | www.bemf.org BOSTON EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2013 FESTIVAL OPERATIC CENTERPIECE , HANDEL ’S ALMIRA Cambridge, MA – April 1, 2012 – The Boston Early Music Festival has announced plans for the 2013 Festival fully-staged Operatic Centerpiece Almira, the first opera by the celebrated and beloved Baroque composer, George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), in its first modern-day historically-conceived production. Written when he was only 19, Almira tells a story of intrigue and romance in the court of the Queen of Castile, in a dazzling parade of entertainment and delight which Handel would often borrow from during his later career. One of the world’s leading Handel scholars, Professor Ellen T. Harris of MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), has said that BEMF is the “perfect and only” organization to take on Handel’s earliest operatic masterpiece, as it requires BEMF’s unique collection of artistic talents: the musical leadership, precision, and expertise of BEMF Artistic Directors Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs; the stimulating and informed stage direction and magnificent production designs of BEMF Stage Director in Residence Gilbert Blin; “the world’s finest continuo team, which you have”; the highly skilled BEMF Baroque Dance Ensemble to bring to life Almira ’s substantial dance sequences; the all-star BEMF Orchestra; and a wide range of superb voices. BEMF will offer five fully-staged performances of Handel’s Almira from June 9 to 16, 2013 at the Cutler Majestic Theatre at Emerson College (219 Tremont Street, Boston, MA, USA), followed by three performances at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center (14 Castle Street, Great Barrington, MA, USA) on June 21, 22, and 23, 2013 ; all performances will be sung in German with English subtitles. -

Swedish Folk Music

Ronström Owe 1998: Swedish folk music. Unpublished. Swedish folk music Originally written for Encyclopaedia of world music. By Owe Ronström 1. Concepts, terminology. In Sweden, the term " folkmusik " (folk music) usually refers to orally transmitted music of the rural classes in "the old peasant society", as the Swedish expression goes. " Populärmusik " ("popular music") usually refers to "modern" music created foremost for a city audience. As a result of the interchange between these two emerged what may be defined as a "city folklore", which around 1920 was coined "gammeldans " ("old time dance music"). During the last few decades the term " folklig musik " ("folkish music") has become used as an umbrella term for folk music, gammeldans and some other forms of popular music. In the 1990s "ethnic music", and "world music" have been introduced, most often for modernised forms of non-Swedish folk and popular music. 2. Construction of a national Swedish folk music. Swedish folk music is a composite of a large number of heterogeneous styles and genres, accumulated throughout the centuries. In retrospect, however, these diverse traditions, genres, forms and styles, may seem as a more or less homogenous mass, especially in comparison to today's musical diversity. But to a large extent this homogeneity is a result of powerful ideological filtering processes, by which the heterogeneity of the musical traditions of the rural classes has become seriously reduced. The homogenising of Swedish folk music started already in the late 1800th century, with the introduction of national-romantic ideas from German and French intellectuals, such as the notion of a "folk", with a specifically Swedish cultural tradition. -

Cash Transfers and Child Schooling

WPS6340 Policy Research Working Paper 6340 Public Disclosure Authorized Impact Evaluation Series No. 82 Cash Transfers and Child Schooling Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation Public Disclosure Authorized of the Role of Conditionality Richard Akresh Damien de Walque Harounan Kazianga Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Development Research Group Human Development and Public Services Team January 2013 Policy Research Working Paper 6340 Abstract The authors conduct a randomized experiment in rural children who are traditionally favored by parents for Burkina Faso to estimate the impact of alternative cash school participation, including boys, older children, and transfer delivery mechanisms on education. The two- higher ability children. However, the conditional transfers year pilot program randomly distributed cash transfers are significantly more effective than the unconditional that were either conditional or unconditional. Families transfers in improving the enrollment of “marginal under the conditional schemes were required to have children” who are initially less likely to go to school, such their children ages 7–15 enrolled in school and attending as girls, younger children, and lower ability children. classes regularly. There were no such requirements under Thus, conditionality plays a critical role in benefiting the unconditional programs. The results indicate that children who are less likely to receive investments from unconditional and conditional cash transfer programs their parents. have a similar impact increasing the enrollment of This paper is a product of the Human Development and Public Services Team, Development Research Group. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. -

Concert Season 34

Concert Season 34 REVISED CALENDAR 2020 2021 Note from the Maestro eAfter an abbreviated Season 33, VoxAmaDeus returns for its 34th year with a renewed dedication to bringing you a diverse array of extraordinary concerts. It is with real pleasure that we look forward, once again, to returning to the stage and regaling our audiences with the fabulous programs that have been prepared for our three VoxAmaDeus performing groups. (Note that all fall concerts will be of shortened duration in light of current guidelines.) In this year of necessary breaks from tradition, our season opener in mid- September will be an intimate Maestro & Guests concert, September Soirée, featuring delightful solo works for piano, violin and oboe, in the spacious and acoustically superb St. Katharine of Siena Church in Wayne. Vox Renaissance Consort will continue with its trio of traditional Renaissance Noël concerts (including return to St. Katharine of Siena Church) that bring you back in time to the glory of Old Europe, with lavish costumes and period instruments, and heavenly music of Italian, English and German masters. Ama Deus Ensemble will perform five fascinating concerts. First is the traditional December Handel Messiah on Baroque instruments, but for this year shortened to 80 minutes and consisting of highlights from all three parts. Then, for our Good Friday concert in April, a program of sublime music, Bach Easter Oratorio & Rossini Stabat Mater; in May, two glorious Beethoven works, the Fifth Symphony and the Missa solemnis; and, lastly, two programs in June: Bach & Vivaldi Festival, as well as our Season 34 Grand Finale Gershwin & More (transplanted from January to June, as a temporary break from tradition), an exhilarating concert featuring favorite works by Gershwin, with the amazing Peter Donohoe as piano soloist, and also including rousing movie themes by Hans Zimmer and John Williams. -

From English to Code-Switching: Transfer Learning with Strong Morphological Clues

From English to Code-Switching: Transfer Learning with Strong Morphological Clues Gustavo Aguilar and Thamar Solorio Department of Computer Science University of Houston Houston, TX 77204-3010 fgaguilaralas, [email protected] Abstract Hindi-English Tweet Original: Keep calm and keep kaam se kaam !!!other #office Linguistic Code-switching (CS) is still an un- #tgif #nametag #buddhane #SouvenirFromManali #keepcalm derstudied phenomenon in natural language English: Keep calm and mind your own business !!! processing. The NLP community has mostly focused on monolingual and multi-lingual sce- Nepali-English Tweet narios, but little attention has been given to CS Original: Youtubene ma live re ,other chalcha ki vanni aash in particular. This is partly because of the lack garam !other Optimistic .other of resources and annotated data, despite its in- English: They said Youtube live, let’s hope it works! Optimistic. creasing occurrence in social media platforms. Spanish-English Tweet In this paper, we aim at adapting monolin- Original: @MROlvera06 @T11gRe go too gual models to code-switched text in various other other cavenders y tambien ve a @ElToroBoots tasks. Specifically, we transfer English knowl- ne ne other English: @MROlvera06 @T11gRe go to cavenders and edge from a pre-trained ELMo model to differ- also go to @ElToroBoots ent code-switched language pairs (i.e., Nepali- English, Spanish-English, and Hindi-English) Figure 1: Examples of code-switched tweets and using the task of language identification. Our their translations from the CS LID corpora for Hindi- method, CS-ELMo, is an extension of ELMo English, Nepali-English and Spanish-English. The LID with a simple yet effective position-aware at- labels ne and other in subscripts refer to named enti- tention mechanism inside its character convo- ties and punctuation, emojis or usernames, respectively lutions. -

Breathtaking-Program-Notes

PROGRAM NOTES In the 16th and 17th centuries, the cornetto was fabled for its remarkable ability to imitate the human voice. This concert is a celebration of the affinity of the cornetto and the human voice—an exploration of how they combine, converse, and complement each other, whether responding in the manner of a dialogue, or entwining as two equal partners in a musical texture. The cornetto’s bright timbre, its agility, expressive range, dynamic flexibility, and its affinity for crisp articulation seem to mimic a player speaking through his instrument. Our program, which puts voice and cornetto center stage, is called “breathtaking” because both of them make music with the breath, and because we hope the uncanny imitation will take the listener’s breath away. The Bolognese organist Maurizio Cazzati was an important, though controversial and sometimes polemical, figure in the musical life of his city. When he was appointed to the post of maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Petronio in the 1650s, he undertook a sweeping and brutal reform of the chapel, firing en masse all of the cornettists and trombonists, many of whom had given thirty or forty years of faithful service, and replacing them with violinists and cellists. He was able, however, to attract excellent singers as well as string players to the basilica. His Regina coeli, from a collection of Marian antiphons published in 1667, alternates arioso-like sections with expressive accompanied recitatives, and demonstrates a virtuosity of vocal writing that is nearly instrumental in character. We could almost say that the imitation of the voice by the cornetto and the violin alternates with an imitation of instruments by the voice. -

DOLCI MIEI SOSPIRI Tra Ferrara E Venezia Fall 2016

DOLCI MIEI SOSPIRI Tra Ferrara e Venezia Fall 2016 Monday, 17 October 6.00pm Italian Madrigals of the Late Cinquecento Performers: Concerto di Margherita Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra Dolci miei sospiri tra Ferrara e Venezia Concerto di Margherita Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra We express our gratitude to Pedro Memelsdorff (VIT'04, ESMUC Barcelona, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice, Utrecht University) for his assistance in planning this concert. Program Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger (1580-1651), Toccata seconda arpeggiata da: Libro primo d'intavolatura di chitarone, Venezia: Antonio Pfender, 1604 Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Voi partite mio sole da: Primo libro d'arie musicali, Firenze: Landini, 1630 Claudio Monteverdi Ecco mormorar l'onde da: Il secondo libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Gardane, 1590 Concerto di Margherita Giovanni de Macque (1550-1614), Seconde Stravaganze, ca. 1610. Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Luzzasco Luzzaschi (ca. 1545-1607), Aura soave; Stral pungente d'amore; T'amo mia vita Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba da: Madrigali per cantare et sonare a uno, e due e tre soprani, Roma: Verovio, 1601 Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1463), T'amo mia vita da: Il quinto libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Amadino, 1605 Luzzasco Luzzaschi Canzon decima a 4 da: AAVV, Canzoni per sonare con ogni sorte di stromenti, Venezia: Raveri, 1608 We express our gratitude to Pedro Memelsdorff Giaches de Wert (1535-1596), O Primavera gioventù dell'anno (VIT'04, ESMUC Barcelona, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice, Utrecht University) da: L'undecimo libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Gardano, 1595 for his assistance in planning this concert. -

The Art of Music :A Comprehensive Ilbrar

1wmm H?mi BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT or Hetirg W, Sage 1891 A36:66^a, ' ?>/m7^7 9306 Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V.9 The art of music :a comprehensive ilbrar 3 1924 022 385 342 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385342 THE ART OF MUSIC The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia UniveTsity Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modem Music Society of New Yoric In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Lillian Nordica as Briinnhilde After a pholo from life THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME NINE The Opera Department Editor: CESAR SAERCHINGER Secretary Modern Music Society of New York Author, 'The Opera Since Wagner,' etc. Introduction by ALFRED HERTZ Conductor San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Formerly Conductor Metropolitan Opera House, New York NEW YORK THE NASTIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC i\.3(ft(fliji Copyright, 1918. by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Bights Reserved] THE OPERA INTRODUCTION The opera is a problem—a problem to the composer • and to the audience. The composer's problem has been in the course of solution for over three centuries and the problem of the audience is fresh with every per- formance. -

Bach Festival the First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation

Bach Festival The First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 1921, 2013 THE 2013 BACH FESTIVAL IS MADE POSSIBLE BY: e Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil DEDICATION ELINORE LOUISE BARBER 1919-2013 e Eighty-rst Annual Bach Festival is respectfully dedicated to Elinore Barber, Director of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 1969-1998 and Editor of the journal BACH—both of which she helped to found. She served from 1969-1984 as Professor of Music History and Literature at what was then called Baldwin-Wallace College and as head of that department from 1980-1984. Before coming to Baldwin Wallace she was from 1944-1969 a Professor of Music at Hastings College, Coordinator of the Hastings College-wide Honors Program, and Curator of the Rinderspacher Rare Score and Instrument Collection located at that institution. Dr. Barber held a Ph.D. degree in Musicology from the University of Michigan. She also completed a Master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music and received a Bachelor’s degree with High Honors in Music and English Literature from Kansas Wesleyan University in 1941. In the fall of 1951 and again during the summer of 1954, she studied Bach’s works as a guest in the home of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Since 1978, her Schweitzer research brought Dr. Barber to the Schweitzer House archives (Gunsbach, France) many times. In 1953 the collection of Dr. Albert Riemenschneider was donated to the University by his wife, Selma. Sixteen years later, Dr. Warren Scharf, then director of the Conservatory, and Dr. -

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(S): Frederick Niecks Source: the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(s): Frederick Niecks Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 42, No. 696 (Feb. 1, 1901), pp. 96-97 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3366388 . Accessed: 21/12/2014 00:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 00:58:46 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions L - g6 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, I901. of any service is, of course, always undesirable. musical society as well as choir inspectorand con- But it is permissible to remind our young and ductor to the Church Choral Association for the enthusiastic present-day cathedral organists that the Archdeaconryof Coventry. In I898 he became rich store of music left to us by our old English church organistand masterof the choristersof Canterbury composers should not be passed by, even on Festival Cathedral,in succession to Dr. -

Takte 1-09.Pmd

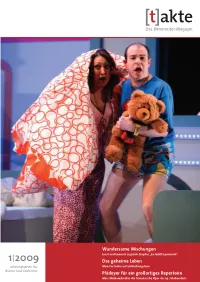

[t]akte Das Bärenreiter-Magazin Wundersame Mischungen Ernst und komisch zugleich: Haydns „La fedeltà premiata” 1I2009 Das geheime Leben Informationen für Miroslav Srnka auf Entdeckungstour Bühne und Orchester Plädoyer für ein großartiges Repertoire Marc Minkowski über die französische Oper des 19. Jahrhunderts [t]akte 481018 „Unheilvolle Aktualität“ Abendzauber Das geheime Leben Telemann in Hamburg Ján Cikkers Opernschaffen Neue Werke von Thomas Miroslav Srnka begibt sich auf Zwei geschichtsträchtige Daniel Schlee Entdeckungstour Richtung Opern in Neueditionen Die Werke des slowakischen Stimme Komponisten J n Cikker (1911– Für Konstanz, Wien und Stutt- Am Hamburger Gänsemarkt 1989) wurden diesseits und gart komponiert Thomas Miroslav Srnka ist Förderpreis- feierte Telemann mit „Der Sieg jenseits des Eisernen Vorhangs Daniel Schlee drei gewichtige träger der Ernst von Siemens der Schönheit“ seinen erfolg- aufgeführt. Der 20. Todestag neue Werke: ein Klavierkon- Musikstiftung 2009. Bei der reichen Einstand, an den er bietet den Anlass zu einer neu- zert, das Ensemblestück „En- Preisverleihung im Mai wird wenig später mit seiner en Betrachtung seines um- chantement vespéral“ und eine Komposition für Blechblä- Händel-Adaption „Richardus I.“ fangreichen Opernschaffens. schließlich „Spes unica“ für ser und Schlagzeug uraufge- anknüpfen konnte. Verwickelte großes Orchester. Ein Inter- führt. Darüber hinaus arbeitet Liebesgeschichten waren view mit dem Komponisten. er an einer Kammeroper nach damals beliebt, egal ob sie im Isabel Coixets Film -

Programma Di Sala

VENITE PASTORES 2006 Milano - Napoli - Roma CURIA GENERALIZIA E PROVINCIA ITALIANA DEI CHIERICI REGOLARI LE COLONNE DEL DECUMANO MUSICAIMMAGINE in collaborazione con Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali ∙ FEC (Fondo Edifici Culto) Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación ∙ Govern de les Illes Balears Regione Abruzzo ∙ Regione Lazio ∙ Provincia di Chieti ∙ Provincia di Napoli Comune di Lanciano ∙ Comune di Napoli Associazione Musicale Euterpe ∙ Basilica di San Giacomo in Augusta Camerata Anxanum ∙ Cappella Musicale di San Giacomo Comitato Presepe Vivente del Centro Antico di Napoli Conservatorio “Nino Rota” di Monopoli ∙ Conservatorio “San Pietro a Majella” di Napoli Croce Rossa Italiana ∙ Ensemble Seicentonovecento ∙ Federculture Feste Musicali Jacopee ∙ Forum Austriaco di Cultura a Milano Forum Austriaco di Cultura a Roma ∙ IMAIE Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum, Salzburg Pontificia Insigne Accademia di Belle Arti e Lettere dei Virtuosi al Pantheon Radio Vaticana ∙ Real Academia de España en Roma Real Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro Rettoria della Chiesa di Sant’Antonio Abate, Milano/Fondazione Ambrosiana Attività Pastorali nell’ambito del progetto multimediale Giacomo Carissimi Maestro dell’Europa Musicale sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica Italiana e del Pontificium Consilium de Cultura GOVERN DE LES REGIONE REGIONE PROVINCIA PROVINCIA COMUNE COMUNE ILLES BALEARS ABRUZZO LAZIO DI CHIETI DI NAPOLI DI NAPOLI DI LANCIANO Venite Pastores 2006 MILANO · napoli · Roma Le Colonne del Decumano ideazione,