Architectural Research in Sweden After Le Corbusier's Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polygon Radial Prints 2 Sessions – 90 Minutes Each

Polygon Radial Prints 2 Sessions – 90 minutes each Essential Question: How can we arrange polygons to show rhythm and movement? Lesson Goal Students create a bilaterally symmetrical design with various types of quadrilaterals (or triangles) and repeatedly print their design to create radial symmetry. Lesson Objectives Students will be able to: • recognize radial movement as a visual concept and apply it to their compositions. • create artworks using a printmaking technique. • describe and classify different types of quadrilaterals (or triangles) in their own and others’ art. Common Core State Standards for Mathematics Reason with shapes and their attributes. Understand that shapes in different categories (e.g., rhombuses, rectangles, and others) may share attributes (e.g., having four sides), and that the shared attributes can define a larger category (e.g., quadrilaterals). Recognize rhombuses, rectangles, and squares as examples of quadrilaterals, and draw examples of quadrilaterals that do not belong to any of these subcategories. California Visual Art Content Standards ARTISTIC PERCEPTION 1.1: Perceive and describe rhythm and movement in works of art and in the environment. CREATI VE EXPRESSION 2.6: Create an original work of art emphasizing rhythm and movement, using a selected printing process. HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL CONTEXT 3.1: Compare and describe various works of art that have a similar theme and were created at a different time. AESTHETIC VALUING 4.1: Compare and contrast selected works of art and describe them, using appropriate -

Jacob Hertzell Styles Sven Markelius's Pythagoras for Bemz

Press release LONDON, October 2015 Jacob Hertzell styles Sven Markelius’s Pythagoras for Bemz in collaboration with Ljungbergs Factory Jacob Hertzell’s curation of Pythagoras – Red by Sven Markelius for Ljungbergs Factory Watch Jacob Hertzell’s curation video here. More high-resolution images here. October 13, 2015 - Bemz, known for its designer covers for IKEA furniture, is very proud to introduce the most quintessential example of 1950s Swedish design, Pythagoras created by Sven Markelius, into its 10th Anniversary Limited Edition Designer-Curated collection. For the launch, Bemz commissioned renowned Swedish stylist, Jacob Hertzell to curate a Pythagoras covered Stockholm sofa with textiles from the existing Bemz collection. Jacob Hertzell created an inspiring milieu that exudes mid-century modern elements with clear references to the ECO-SOC session hall of the UN building in New York for which the fabric was originally created. Sven Markelius (1889-1972) was one of Sweden’s most iconic 20th century designers and a strong advocate of Swedish Functionalism. Several of his well-known textile patterns, such as Pythagoras and Prisma, have been exhibited internationally as representatives of 1950s Swedish textile design. Press release Sven Markelius / Ljungbergs Factory & Bemz – October 13, 2015 !1 The hand-printed pattern Pythagoras was originally created in 1952 when Sven Markelius participated in the architectural group designing the UN-buildings in New York. The team included other prominent architects such as Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer. Tasked with designing the session hall for economic and social issues in 1952, Sven Markelius came up with the hand- printed pattern, Pythagoras for a curtain made of elegant velvet. -

Paimio Sanatorium

MARIANNA HE IKINHEIMO ALVAR AALTO’S PAIMIO SANATORIUM PAIMIO AALTO’S ALVAR ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: : PAIMIO SANATORIUM ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium TIIVISTELMÄ rkkitehti, kuvataiteen maisteri Marianna Heikinheimon arkkitehtuurin histo- rian alaan kuuluva väitöskirja Architecture and Technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio A Sanatorium tarkastelee arkkitehtuurin ja teknologian suhdetta suomalaisen mestariarkkitehdin Alvar Aallon suunnittelemassa Paimion parantolassa (1928–1933). Teosta pidetään Aallon uran käännekohtana ja yhtenä maailmansotien välisen moder- nismin kansainvälisesti keskeisimpänä teoksena. Eurooppalainen arkkitehtuuri koki tuolloin valtavan ideologisen muutoksen pyrkiessään vastaamaan yhä nopeammin teollis- tuvan ja kaupungistuvan yhteiskunnan haasteisiin. Aalto tuli kosketuksiin avantgardisti- arkkitehtien kanssa Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne -järjestön piirissä vuodesta 1929 alkaen. Hän pyrki Paimion parantolassa, siihenastisen uransa haastavim- massa työssä, soveltamaan uutta näkemystään arkkitehtuurista. Työn teoreettisena näkökulmana on ranskalaisen sosiologin Bruno Latourin (1947–) aktiivisesti kehittämä toimijaverkkoteoria, joka korostaa paitsi sosiaalisten, myös materi- aalisten tekijöiden osuutta teknologisten järjestelmien muotoutumisessa. Teorian mukaan sosiaalisten ja materiaalisten toimijoiden välinen suhde ei ole yksisuuntainen, mikä huo- mio avaa kiinnostavia näkökulmia arkkitehtuuritutkimuksen kannalta. Olen ymmärtänyt arkkitehtuurin -

Nordic Classicism : Scandinavian Architecture 1910-1930 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NORDIC CLASSICISM : SCANDINAVIAN ARCHITECTURE 1910-1930 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Stewart | 208 pages | 06 Feb 2020 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781350154445 | English | London, United Kingdom Nordic Classicism : Scandinavian Architecture 1910-1930 PDF Book Visit the Australia site Continue on UK site. Engagement: Town Hall in Denmark. The only applied decoration is a relief of the Swedish coat of arms above the main entrance. About this product. Aalto was married twice. In the Nordic countries the lighting conditions and the weather are constantly changing. Finally, the best way to contemplate on Scandinavian architecture is to take a look at the examples. For the farmers and fishermen things need only be simple, basic, useful and essential. Alvar Aalto is remembered with the likes of Gropius, Le Corbusier, and van der Rohe as a major influence on 20th century modernism. Show More Show Less. But as time went on, they got more complex. See all in World Architecture. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. Yet what was conceived before tended to get overshadowed, such that socalled Swedish Grace with its classical resonances appeared alien to avant-gardism. Yet this brief classsical movement was quickly eclipsed by the rise of international modernism, and has often been overlooked in architectural studies. Go To Basket. Learn more…. The original occupant, also known in English as the Social Security Administration, remained until They were built of wood, and had stone walls around the base. -

Sven Markelius and Uno Åhrén

A Tribute to the Memory of Sven Markelius and Uno Åhrén by Eva Rudberg, PhD. Dr. Tech. architect, associate professor and former researcher at Arkitekturmuseet (museum of architecture) Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) 1 2 A Tribute to the Memory of Sven Markelius and Uno Åhrén Presented at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences by Eva Rudberg, PhD. Dr. Tech. architect, associate professor and former researcher at Arkitekturmuseet (museum of architecture) 3 The Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) is an independent, learned society that promotes the engineering and economic sciences and the development of industry for the benefit of Swedish society. In cooperation with the business and academic communities, the Academy initiates and proposes measures designed to strengthen Sweden’s industrial skills base and competitiveness. For further information, please visit IVA’s website at www.iva.se. Published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), Eva Rudberg, Phd. Dr., architect, associate professor and former researcher at Arkitekturmuseet (museum of architecture) IVA, P.O. Box 5073, SE-102 42 Stockholm, Sweden Phone: +46 8 791 29 00 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iva.se IVA-M 490 • ISSN 1102-8254 • ISBN 978-91-7082-964-2 Editor: Anna Lindberg, IVA Translation: Diane Hogsta Layout and production: Hans Melcherson, Grafisk Form, Stockholm, Sweden Photos: ArkDes, Lennart Nilsson, Lennart Olsson, Bo Törngren, Karl Schultz, Barbro Soller Printed by Pipline, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017 4 Foreword Each year the Royal at Kungsträdgården park in Stockholm. Swedish Academy of He planned suburbs such as Björkhagen, Engineering Sciences Högdalen and Vällingby while serving as (IVA) produces a book urban planning director in Stockholm. -

Lecture Handouts, 2013

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #1 INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW Introductions Expectations Textbooks Assignments Electronic reserves Research Project Sources History-Theory-Criticism Methods & questions of Architectural History Assignments: Initial Paper Topic form Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #2 ARCHITECTURE OF WWII The World at War (1939-45) Nazi War Machine - Rearming Germany after WWI Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect & responsible for Nazi armaments Autobahn & Volkswagen Air-raid Bunkers, the “Atlantic Wall”, “Sigfried Line”, by Fritz Todt, 1941ff Concentration Camps, Labor Camps, POW Camps Luftwaffe Industrial Research London Blitz, 1940-41 by Germany Bombing of Japan, 1944-45 by US Bombing of Germany, 1941-45 by Allies Europe after WWII: Reconstruction, Memory, the “Blank Slate” The American Scene: Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941 Pentagon, by Berman, DC, 1941-43 “German Village,” Utah, planned by US Army & Erich Mendelsohn Military production in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Akron, Cleveland, Gary, KC, etc. Albert Kahn, Detroit, “Producer of Production Lines” * Willow Run B-24 Bomber Plant (Ford; then Kaiser Autos, now GM), Ypsilanti, MI, 1941 Oak Ridge, TN, K-25 uranium enrichment factory; town by S.O.M., 1943 Midwest City, OK, near Midwest Airfield, laid out by Seward Mott, Fed. Housing Authortiy, 1942ff Wartime Housing by Vernon Demars, Louis Kahn, Oscar Stonorov, William Wurster, Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, Skidmore-Owings-Merrill, et al * Aluminum Terrace, Gropius, Natrona Heights, PA, 1941 Women’s role in the war production, “Rosie the Riverter” War time production transitions to peacetime: new materials, new design, new products Plywod Splint, Charles Eames, 1941 / Saran Wrap / Fiberglass, etc. -

Sigurd Lewerentz, Architect: 1885-1975 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SIGURD LEWERENTZ, ARCHITECT: 1885-1975 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janne Ahlin | 208 pages | 15 Feb 2015 | Park Books | 9783906027487 | English | Zurich, Switzerland Sigurd Lewerentz, Architect: 1885-1975 PDF Book Contact seller. These include St. Garden view. Sigurd Lewerentz, Architect is a reprint of the first ever monograph on his work, originally published in English and long out of print. Add to Watchlist. Yet it was his architectural apprenticeship in Munich that set him on his path as an architect, opening his own office in Stockholm in Go To Basket. Enter email address to Subscribe. We are unable to deliver faster than stated. An early model of Villa Edstrand, c. Learn more - eBay Money Back Guarantee - opens in new window or tab. Recently, we found ourselves in one of those situations. Estimated delivery business days. He built, diligently and poetically, resisting the urge — if it ever existed — to define the ethics or aesthetic framework which bound together his body of work. ISSN Item Information Condition:. He continued to work at competition proposals and furniture designs until shortly before his death in Lund , Sweden during This only lasted a year and soon after Lewerentz opened an office in partnership with another young architect named Torsten Stubelius after Lewerentz formed his own firm. Another commission Leverentz won through a competition, the National Insurance Institute completed in was nicknamed the funkispalats Functionalist palace , which captures the transitional character of this building and its times. Item added to your basket. And again with some younger cutting edge architects. This item will be shipped through the Global Shipping Program and includes international tracking. -

Gunnar Asplund Free

FREE GUNNAR ASPLUND PDF Peter Blundell Jones | 240 pages | 13 Feb 2012 | Phaidon Press Ltd | 9780714863153 | English | London, United Kingdom 70+ Best Gunnar Asplund images | gunnar, architect, architecture Vatican City participated in Gunnar Asplund Venice Architecture Biennale for the first time this year, Gunnar Asplund the public to explore a sequence of unique chapels designed by Gunnar Asplund architects including Norman Foster and Eduardo Souto de Moura. As members of the public circulate through the chapels in each shot, the scenes give an impression of how each chapel guides circulation. In a world in which the "happy" architectural image feels all-pervasive, the British architect and academic Dr. Timothy Brittain-Catlin reveals its darker side suggesting why, and how, we might come to celebrate it. You can read Brittain-Catlin's essays on British postmodernism hereand on colorful architecture, here. This is what at my school we call an "announcement", rather than a statement of fact. Indeed, all architects and architecture students hear these words all the time. But are they Gunnar Asplund Should they be? The Nordic nations—Finland, Norway and Sweden—have reached a pivotal point in their collective, and individual, architectural identities. The Grandfathers of the Gunnar Asplund Nordic style—including the likes of Sverre FehnPeter CelsingGunnar AsplundSigurd Lewerentz, Alvar Aaltoand Eero Saarinen—provided a foundation upon which architects and designers since have both thrived on and been confined by. The Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale —directed by Alejandro Aravena —will be the moment to probe: to discuss, argue, debate and challenge what Nordic architecture really is and, perhaps more importantly, what it could be in years to come. -

Interior Topography and the Fabric of Terrain

1 Interior topography and the fabric of terrain A starting point: A useful starting point for us is to ask what could these two activities: Interior and Landscape design, possibly have in common, particularly when human artefacts and processes are often thought of as being in opposition to the natural world. However, both designers of Interiors and landscapes are engaged in producing cultural artefacts. Both set out to create environments to enable people to live, work and play and no matter how “natural” a landscape appears to be, for example Central Park in New York it is, as Jonathan Bate reminds us “a work of art, it is a representation of the state of nature “ Bate (2000) pg 63-64, and therefore as much a product of human culture as any interior. They are both cultural practices. We seek to locate our observations on the relationship between Interiors and landscapes by looking at the impact of modernism on them both, and in particular the manner in which modernist conceptions of space have affected not only them, but all environmental disciplines We propose that Interior and Landscape design, and experience, share common characteristics of surface, dressing, performance, transience and potential. The argument is presented in two parts: Part 1 outlines general propositions that pertain to both interior and landscape design practices, where conditions of nature and culture, nature and art, are seen as overlapping and correspondent. 2 Part 2 examines these characteristics in the context of the Woodland Cemetery Stockholm, designed by Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz, principally between 1915 and 1940. -

Newtownpub-180212Vallingby.Pdf

New Towns on the Cold War Frontier Content Dodoma, Tanzania 468 *Prologue 12 Zanzibar New Town 550 A Thousand and One Garden Cities 1899-1945 The Origin and Pedigree of the New Towns Model Ciudad Guyana, Venezuela 586 Changpin, China 592 *Chapter 1 24 “An Iron Curtain has descended across the continent” Islamabad, Pakistan 598 The First Generation New Towns in the West and the Eastern Block Hanoi Vietnam 604 Stevenage, England 30 Kabul, Afghanistan 610 Hoogvliet, The Netherlands 36 Habana del Este, Cuba 616 Westelijke Tuinsteden, The Netherlands 60 Unidad Independencia, Mexico 622 Vällingby, Sweden 66 Nowe Tychy, Poland 274 *Chapter 3 716 Vernacular Spectacular Neo Beograd, Serbia 280 Critique from the Inside-Out on the Diagrams of the New Towns Eisenhuttenstadt, Germany 286 Toulouse Le Mirail, France 722 23 de Enero, Caracas 292 Poulad Shahr, Iran 728 Rourkela, India 734 *Chapter 2 298 Export to Developing Countries 10th of Ramadan, Egypt 740 Urban Planning as a Weapon in the Cold War Milton Keynes, United Kingdom 746 Arad, Israël 304 Baghdad, Iraq 310 *Epilogue 752 How to survive the twentieth century? Tema, Ghana 316 The fate of the old New Town, the rise of the new generation, and the ongoing search for context. Against a sky with cumulus clouds, the Swedish New Town Vällingby’s logo is watching over you as a giant blue eye visible from every angle. Bent in neon the turning Vällingby, Sweden V-sign is striving aft er a utopia, however, reminding you that you are close to Sweden’s capital Stockholm. Although the community centre Vällingby Centrum has acquired the Anglicism of Vällingby City, the similarity with the famous images that toured architectural journals worldwide fi ve decades ago is striking: the same characteristic TOO GOOD TO BE lampposts, the same typography snaking on signs, the same fountain with pigeons and locals, resting on benches. -

Infrastructural Imaginaries in Scandinavia

INFRASTRUCTURAL IMAGINARIES IN SCANDINAVIA GSAPP 2018 SUMMER WORKSHOP TEI CARPENTER & JESSE LECAVALIER JULY 25 - AUGUST 10 TEI CARPENTER JESSE LECAVALIER Tei Carpenter is an architectural designer, educator and Jesse LeCavalier (LECAVALIER R+D) is a designer, writer, founder of Brooklyn based design studio Agency—Agency. and educator whose work explores the architectural and The studio’s recently completed work includes a new urban implications of contemporary logistics. He is the non-profit headquarters in downtown Houston and a winning author of The Rule of Logistics: Walmart and the entry for LA+ Journal’s island competition. In 2018, Architecture of Fulfillment (University of Minnesota Agency—Agency was a winner of the New Practices New York Press, 2016). He is Assistant Professor of Architecture award from the American Institute of Architects. She is at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and the Daniel Adjunct Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s Rose Visiting Assistant Professor at Yale School of Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Architecture. Preservation and Director of the Waste Initiative, an applied research and design platform. LeCavalier is a 2018 MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program finalist for his project SHELF LIFE and his installation Carpenter’s design and research work into architecture’s “Architectures of Fulfillment” was recently part of the entanglement with emerging natures has been supported by 2017 Seoul Biennale for Architecture and Urbanism. the New York State Council on the Arts and has been Recognition for teaching includes the 2015 New Faculty exhibited at the Storefront for Art and Architecture and Teaching Award from the Association of the Collegiate at the 2016 Venice Biennale. -

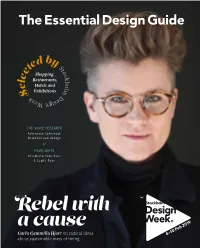

Rebel with a Cause

The Essential Essential Design Guide Design Guide by d by S t te o c Shopping, c k e Restaurants, h l o Hotels and l e m S Exhibitions D e k s e i e g n W THE SPACE DESIGNER Astronaut lifestyle inspires new design // HIGHLIGHTS Stockholm Furniture & Light Fair by Rebel with a cause Carla Cammilla Hjort on radical ideas about sustainable ways of living In 2018, the collaboration between Note Design Studio and Tarkett resulted in The Lookout, selected as the ”Editors’ Choice Award for Best Stand” at Stockholm Furniture Fair, short-listed on Dezeen Design Awards and acclaimed internationally by design publications. This year’s installation Snowtopped, exhibited in the center of Stockholm, further showcases the possibilities of Tarkett materials by exploring the colors and shapes of snow. Snowtopped Stockholm When: Monday, February 4 and continue throughout Stockholm Design Week Where: Stockholm under Stjärnorna, Brunkebergstorg 2 2019 Annons_The Stockholm Design Week_380x240.indd 1 2018-11-15 20:41 A net of electroluminescent cables wraps the façade of the Italian Cultural Institute designed by Gio’ Ponti in Stockholm. The art instal- lation, called RELATIONAL, is a work by the Italian artists Bianco- Valente. The blue lining in the darkness of the Diplomatic neighbor- Welcome to meet the darkness, hood highlights the role and the mission of the Institute as much as it represents aesthetically the exchanges and the relationships between individuals and cultures. the cold and the warm hospitality — at the launch of the 18th edition of Stockholm Design Week! AS ONE OF the major centers of contemporary Stay informed European innovation, Stockholm attracts the very Participating companies and cutting-edge international entrepreneurs, tech start-ups events will be announced at Five Italian architects furnish the Auditorium window, each and students, but the city is also a fascinating destination one with a design object meant to be a tribute to Gio’ Ponti.