The Beginning of Byzantine Chronography: John Malalas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86543-2 - Economy and Society in the Age of Justinian Peter Sarris Excerpt More information Introduction In the year 565, in the imperial capital of Constantinople, the Emperor Justinian died, bringing to a close a reign that had lasted some forty-eight years. In death, as in life, Justinian left a deep impression on those around him. The Latin court poet Corippus declared that ‘the awesome death of the man showed by clear signs that he had conquered the world. He alone, amidst universal lamentations, seemed to rejoice in his pious coun- tenance.’1 The memory of Justinian was to loom large in the minds of subsequent generations of emperors, just as the physical monuments built in Constantinople during his reign were long to dominate the medieval city.2 The emperor had reformed the civil law of the empire, overhauled its administrative structures, and restored imperial rule to Africa, Italy, and part of Spain; he had engaged in long drawn-out warfare with the prestige enemy of Sasanian Persia and attempted to restore peace to the increasingly fissile imperial Church. In short, through his military exertions, Justinian had done much to restore the Roman Empire to a position of military and ideological dominance in the lands bordering the central and western Mediterranean, whilst at home he had sought to bolster the legal, admin- istrative, and religious authority of the imperial office.3 This attempted restoration of imperial fortunes had been accompanied by a concerted effort to propagandise on behalf of the emperor and his policies. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

Roman Empire Roman Empire

NON- FICTION UNABRIDGED Edward Gibbon THE Decline and Fall ––––––––––––– of the ––––––––––––– Roman Empire Read by David Timson Volum e I V CD 1 1 Chapter 37 10:00 2 Athanasius introduced into Rome... 10:06 3 Such rare and illustrious penitents were celebrated... 8:47 4 Pleasure and guilt are synonymous terms... 9:52 5 The lives of the primitive monks were consumed... 9:42 6 Among these heroes of the monastic life... 11:09 7 Their fiercer brethren, the formidable Visigoths... 10:35 8 The temper and understanding of the new proselytes... 8:33 Total time on CD 1: 78:49 CD 2 1 The passionate declarations of the Catholic... 9:40 2 VI. A new mode of conversion... 9:08 3 The example of fraud must excite suspicion... 9:14 4 His son and successor, Recared... 12:03 5 Chapter 38 10:07 6 The first exploit of Clovis was the defeat of Syagrius... 8:43 7 Till the thirtieth year of his age Clovis continued... 10:45 8 The kingdom of the Burgundians... 8:59 Total time on CD 2: 78:43 2 CD 3 1 A full chorus of perpetual psalmody... 11:18 2 Such is the empire of Fortune... 10:08 3 The Franks, or French, are the only people of Europe... 9:56 4 In the calm moments of legislation... 10:31 5 The silence of ancient and authentic testimony... 11:39 6 The general state and revolutions of France... 11:27 7 We are now qualified to despise the opposite... 13:38 Total time on CD 3: 78:42 CD 4 1 One of these legislative councils of Toledo.. -

Collector's Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage

Liberty Coin Service Collector’s Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage (49 BC - AD 518) The Twelve Caesars - The Julio-Claudians and the Flavians (49 BC - AD 96) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Julius Caesar (49-44 BC) Augustus (31 BC-AD 14) Tiberius (AD 14 - AD 37) Caligula (AD 37 - AD 41) Claudius (AD 41 - AD 54) Tiberius Nero (AD 54 - AD 68) Galba (AD 68 - AD 69) Otho (AD 69) Nero Vitellius (AD 69) Vespasian (AD 69 - AD 79) Otho Titus (AD 79 - AD 81) Domitian (AD 81 - AD 96) The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (AD 96 - AD 192) Nerva (AD 96-AD 98) Trajan (AD 98-AD 117) Hadrian (AD 117 - AD 138) Antoninus Pius (AD 138 - AD 161) Marcus Aurelius (AD 161 - AD 180) Hadrian Lucius Verus (AD 161 - AD 169) Commodus (AD 177 - AD 192) Marcus Aurelius Years of Transition (AD 193 - AD 195) Pertinax (AD 193) Didius Julianus (AD 193) Pescennius Niger (AD 193) Clodius Albinus (AD 193- AD 195) The Severans (AD 193 - AD 235) Clodius Albinus Septimus Severus (AD 193 - AD 211) Caracalla (AD 198 - AD 217) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Geta (AD 209 - AD 212) Macrinus (AD 217 - AD 218) Diadumedian as Caesar (AD 217 - AD 218) Elagabalus (AD 218 - AD 222) Severus Alexander (AD 222 - AD 235) Severus The Military Emperors (AD 235 - AD 284) Alexander Maximinus (AD 235 - AD 238) Maximus Caesar (AD 235 - AD 238) Balbinus (AD 238) Maximinus Pupienus (AD 238) Gordian I (AD 238) Gordian II (AD 238) Gordian III (AD 238 - AD 244) Philip I (AD 244 - AD 249) Philip II (AD 247 - AD 249) Gordian III Trajan Decius (AD 249 - AD 251) Herennius Etruscus -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40589-9 - Byzantine Style, Religion and Civilization: In Honour of Sir Steven Runciman Elizabeth Jeffreys Index More information Index Aaron 11, 13 Apion I, Flavius 419 Abbas Hierax, and Apion family 419, 422 Apion II, Flavius 418–19 Abgar of Edessa 192, 193 Apion III, Flavius 418, 420, 422–3 letter (in Constantinople) 198–9 Apion IV, Flavius 420–1 Acre, crusader scriptorium 165, 167 Apion papyri 419, 421; see also Oxyrhynchus Acta Davidis, Symeonis et Georgii 362, 364, and evidence for administration of 365 estates 421 chronology for pardon of and evidence for family involvement 421–2 Theophilos 366–70 architecture, military, Crusader and quality of as source 363–4 Byzantine 159–62 Symeon’s role in 366, 367, 368, 369 ark of the covenant 9, 14 Aetios, papias 182 armed pilgrimage 253–4 Agat‘angelos, ‘History of Armenia’ 185–6 and knights as small group leaders 253 Agios Ioannis, alternative names for 43 garrisons to guard communications 259–60 port of 41–3 Armenian traditions in 9th cent. routes from 44 Constantinople 186, 187 Alan princess, a hostage 150 Askalon, fortress and shrine 261–2 Alexander, emperor 341, 344 Asotˇ Bagratuni 181, 182, 209, 218 Alexios I Komnenos, letter to Robert of Attaleiates, Michael 244 Flanders 253, 260, 261 Attaleiates, Michael, Diataxis of 244–6; see also on armed pilgrimage 254 Monastery of the Hospice of Al-Idrisi, and Gulf of Dyers 58 All-Merciful Christ Alisan,ˇ L. M., and ‘Discovery of the Relics of the Holy Illuminator’ 177 B. L., Egerton 1139 165–7, 168 Amphilochia, date of first part 210 ‘Basilios’ 166 date of whole work 211 and Jerusalem 165 nature of 209, 210–11 miniatures 166 of Photios painters 166 real addressee of? 211–12 Queen Melisende’s Psalter? 165, 167 so-called, of Basil of Caesarea 212 Bagrat, son of king of Georgia 150 sources used 213–14 Bajezid I 74, 75, 76, 78 theology of 209–10 Balfour, A. -

Basiliscus the Boy-Emperor , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 24:1 (1983:Spring) P.81

CROKE, BRIAN, Basiliscus the Boy-Emperor , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 24:1 (1983:Spring) p.81 Basiliscus the Boy-Emperor Brian Croke OR THE FIFTH AND SIXTH centuries the Chronicle of Victor of F Tunnuna is a valuable source that deserves close inspection. What may not always be sufficiently appreciated, because Victor is most frequently referred to as an African bishop and because he wrote in Latin, is that he spent a good deal of his later life in Con stantinople. His Chronicle, which covers the years 444-567, was in fact written in Constantinople and is a generally well-informed source for events in the East during this period.1 Like so many other African bishops, Victor fell foul of his sover eign Justinian by defending the works condemned by the emperor in 543 in the so-called Three Chapters edict. This resulted in a trying period of internment for Victor in the Mandracion monastery near Carthage, then on the Balearic Islands, then Algimuritana, and finally with his episcopal colleague Theodore of Cebaruscitana in the prison of the Diocletianic fortress behind the governor's palace in Alexan dria (Chron. s.a. 555.2, p.204). In 556 after a twelve-day trial in the praetorium Victor and Theodore were transferred to the Tabennesiote monastery near Canopus, twelve miles east of Alexandria (556.2, p.204). Nine years later, at the request of Justinian himself, Victor and Theodore were summoned from Egypt. At the imperial court they stood their ground in the argument over the 'Three Chapters' with both Justinian and the patriarch Eutychius. -

The Gender of Money: Byzantine Empresses on Coins (324–802)’ Gender & History, Vol.12 No

Gender & History ISSN 0953–5233 Leslie Brubaker and Helen Tobler, ‘The Gender of Money: Byzantine Empresses on Coins (324–802)’ Gender & History, Vol.12 No. 3 November 2000, pp. 572–594. The Gender of Money: Byzantine Empresses on Coins (324–802) Leslie Brubaker and Helen Tobler Coins played different roles in the ancient and medieval worlds from those that they play in the economy today. In the late antique and early Byzantine world – that is, roughly between 300 and 800 – there were in a sense two currencies: gold coins and base metal (copper) coins. Both were minted and distributed by the state, but the gold solidi (in Latin) or nomismata (in Greek), introduced in 309, were by the end of the fifth century in practice used above all for the payment of tax and for major transactions such as land sales, while the copper coins (nummi, replaced in 498 by folles) were broadly the currency of market transactions.1 Another striking difference is that late antique and Byzantine coin types changed with great frequency: as an extreme example, Maria Alföldi catalogued over seven hundred different types for a single emperor, Constantine I the Great (306–37, sole ruler from 324).2 There are many reasons for this, but one of the most import- ant has to do with communication: centuries before the advent of the press, images on coins were a means to circulate information about the state. This is particularly true of the first three and a half centuries covered by this article. While the extent to which coins were used in daily exchange transactions is still uncertain, and was very variable, the frequency with which they appear in archaeological excavations of urban sites throughout the former eastern Roman empire until 658 indicates their wide diffusion. -

Brian Croke Tradition and Originality in Photius' Historical Reading

Brian Croke Tradition and Originality in Photius' Historical Reading 1. Approaching Byzantine Historiography Byzantine historiography remains an under-developed field. There is no dedicated and comprehensive modern study, certainly nothing to match the several substantial surveys of western medieval historiography. What we do have, however, is the two-volume compilation by Karpozilos 1 (a pioneering work in itselt) and an assortment of instructive articles by Jacob Ljubarskij, Riccardo Maisano, Athanasios Markopoulos, Ruth Macrides and others. 2 The task is by no means as difficult as it was twenty-five to thirty years ago. In the interim, there have appeared editions and/or English translations of a raft of crucial texts: Malalas, Agathias, Menander, Evagrius, Chronicon Paschale, Theophylact, Nicephorus, Synkellos, Theophanes, Genesios, Kinnamos, Eustathius and Niketas Choniates. Others are pending, notably Skylitzes, Leo the Deacon, Acropolites, Nikephoros Bryennios (the Younger) and Kedrenos, white several others have appeared in other languages: Pachymeres, Skylitzes and Nikephoros Bryennios in French, with Nikephoros Gregoras, Acropolites, Skylitzes (but incomplete) and Genesios in German. In addition, recent translations of several Armenian and Syriac histories and chronicles will also be important in improving understanding of the nature and role of historiography in the Byzantine world, particularly their connection with the writing of histories 1. A. Karpozilos, Bv(al'Tu,oi 'knoptKoi rni Xpovoypá<j>ot (2 vols Athens 1997- 2002). 2. J.N. Ljubarskij, 'Neue Tendenzen in der Erforschung der byzantinischen Historiographie' Klio 69 (1987) 560-6; J.N. Ljubarskij, 'Man in Byzantine Historiography from John Malalas to Michael Psellus' DOP 46 (1992) 177-86; J.N. Ljubarskij, "New Trends in the Study of Byzantine Historiography' DOP 47 ( 1993) 131-8; R. -

Zur Kritik Des Johannes Von Antiocha, by Georgios Sotiriadis

The Classical Review http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR Additional services for The Classical Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Zur Kritik des Johannes von Antiocha, by Georgios Sotiriadis. Leipzig, 1887. 3 Mk. 20. John B. Bury The Classical Review / Volume 2 / Issue 07 / July 1888, pp 208 - 209 DOI: 10.1017/S0009840X00192972, Published online: 27 October 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009840X00192972 How to cite this article: John B. Bury (1888). The Classical Review, 2, pp 208-209 doi:10.1017/S0009840X00192972 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR, IP address: 138.251.14.35 on 09 Apr 2015 208 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. Theoricon. On Olynth. i. 19 we read 'After Apollo- again Dr. Holden has undertaken the work of dorus' condemnation Eubulus got a law passed enact- editor, giving us a companion volume to the Lives of ing capital punishment for any one proposing this the Gracchi and of Sulla. All students of Plutarch, in future (i.e. proposing to apply the surplus to war).' an increasing number as they bid fair to be under the The scholiast on Olynth. i. 1 is quoted as the authority stimulus of the Cambridge Board of Classical Studies, for this fact, but the editors embody the scholiast's will find all, more than all perhaps, that they require ; statement in their own summary of the case. On the besides the notes which are of course very full and other hand on Olyntk. iii. -

Byzantion, Zeuxippos, and Constantinople: the Emergence of an Imperial City

Constantinople as Center and Crossroad Edited by Olof Heilo and Ingela Nilsson SWEDISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE IN ISTANBUL TRANSACTIONS, VOL. 23 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................... 7 OLOF HEILO & INGELA NILSSON WITH RAGNAR HEDLUND Constantinople as Crossroad: Some introductory remarks ........................................................... 9 RAGNAR HEDLUND Byzantion, Zeuxippos, and Constantinople: The emergence of an imperial city .............................................. 20 GRIGORI SIMEONOV Crossing the Straits in the Search for a Cure: Travelling to Constantinople in the Miracles of its healer saints .......................................................... 34 FEDIR ANDROSHCHUK When and How Were Byzantine Miliaresia Brought to Scandinavia? Constantinople and the dissemination of silver coinage outside the empire ............................................. 55 ANNALINDEN WELLER Mediating the Eastern Frontier: Classical models of warfare in the work of Nikephoros Ouranos ............................................ 89 CLAUDIA RAPP A Medieval Cosmopolis: Constantinople and its foreigners .............................................. 100 MABI ANGAR Disturbed Orders: Architectural representations in Saint Mary Peribleptos as seen by Ruy González de Clavijo ........................................... 116 ISABEL KIMMELFIELD Argyropolis: A diachronic approach to the study of Constantinople’s suburbs ................................... 142 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS MILOŠ -

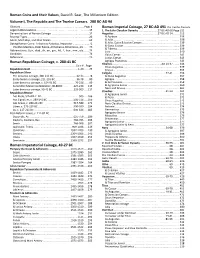

Roman Coins and Their Values, David R. Sear, the Millenium

Roman Coins and their Values , David R. Sear, The Millenium Edition Volume I, The Republic and The Twelve Caesars. 280 BC-AD 96 Glossary ........................................................................ ............ Page 8 Roman Imperial Coinage, 27 BC-AD 491 The Twelve Caesars Legend Abbreviations ................................................... ................... 15 1. The Julio-Claudian Dynasty .........................27 BC-AD 68 . Page 311 Denominations of Roman Coinage .............................. ................... 17 Augustus ...........................................................27 BC-AD 14 ......... 312 Reverse Types ............................................................... ................... 26 & Agrippa ......................................................................... ......... 336 Mints, Mint Map, and Mint Marks................................ ................... 65 & Julia ............................................................................... ......... 338 Dating Roman Coins: Tribunicia Potestas, Imperator .. ................... 72 & Julia, Gaius & Lucius Caesars ........................................ ......... 339 Pontifex Maximus, Pater Patrae, Armeniacus, Britannicus, etc. ....... 73 & Gaius Caesar ................................................................. ......... 339 & Tiberius ......................................................................... ......... 339 Abbreviations: Cuir., diad., dr., ex., gm., hd., l., laur., mm., etc ........ 74 Livia .................................................................................