Potential Replacement for Peat in Horticulture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 30 Origins of Horticultural Science

Lecture 30 1 Lecture 30 Origins of Horticultural Science The origin of horticultural science derives from a confl uence of 3 events: the formation of scientifi c societies in the 17th century, the creation of agricultural and horticultural societies in the 18th century, and the establishment of state-supported agricultural research in the 19th century. Two seminal horticultural societies were involved: The Horticultural Society of London (later the Royal Horticulture Society) founded in 1804 and the Society for Horticultural Science (later the American Society for Horticultural Science) founded in 1903. Three horticulturists can be considered as the Fathers of Horticultural Science: Thomas Andrew Knight, John Lindley, and Liberty Hyde Bailey. Philip Miller (1691–1771) Miller was Gardener to the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries at their Botanic Garden in Chelsea and is known as the most important garden writer of the 18th century. The Gardener’s and Florist’s Diction- ary or a Complete System of Horticulture (1724) was followed by a greatly improved edition entitled, The Gardener’s Dictionary containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit and Flower Garden (1731). This book was translated into Dutch, French, German and became a standard reference for a century in both England and America. In the 7th edition (1759), he adopted the Linnaean system of classifi cation. The edition enlarged by Thomas Martyn (1735–1825), Professor of Botany at Cambridge University, has been considered the largest gardening manual to have ever existed. Miller is credited with introducing about 200 American plants. The 16th edition of one of his books, The Gardeners Kalendar (1775)—reprinted in facsimile edition in 1971 by the National Council of State Garden Clubs—gives direc- tions for gardeners month by month and contains an introduction to the science of botany. -

Tree Pruning: the Basics! Pruning Objectives!

1/12/15! Tree Pruning: The Basics! Pruning Objectives! Improve Plant Health! Safety! Aesthetics! Bess Bronstein! [email protected] Direct Growth! Pruning Trees Increase Flowers & Fruit! Remember-! Leaf, Bud & Branch Arrangement! ! Plants have a genetically predetermined size. Pruning cant solve all problems. So, plant the right plant in the right way in the right place.! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees 1! 1/12/15! One year old MADCap Horse, Ole!! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Internode Maple! Ash! Horsechestnut! Dogwood! Oleaceae! Node Caprifoliaceae! Most plants found in these genera and families have opposite leaf, bud and branch arrangement.! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees One year old Node & Internode! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Internode Node! • Buds, leaves and branches arise here! Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth Internode! and tree vigor! • Stem area between Node nodes! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees 2! 1/12/15! One year old Stem & Buds! Two years old Dormant Buds! Three years old Internode Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth and tree vigor! Node Latent bud - inactive lateral buds at nodes! Latent! Adventitious" Adventitious bud! - found in unexpected areas (roots, stems)! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees One year old Epicormic Growth! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Growth from dormant buds, either latent or adventitious. Internode These branches are weakly attached.! Axillary (lateral) bud - found along branches below tips! Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth and tree vigor! Node -

Introduction to Horticulture 3

1 Introduction to Horticu ltu re INTRODUCTION Horticulture is a science, as well as, an art of production, utilisation and improvement of horticultural crops, such as fruits and vegetables, spices and condiments, ornamental, plantation, medicinal and aromatic plants. Horticultural crops require intense care in planting, carrying out intercultural operations, manipulation of growth, harvesting, packaging, marketing, storage and processing. India is the second largest producer of fruits and vegetables in the world after China. In India, about 55–60 per cent of the total population depends on agriculture and allied activities. Horticultural crops constitute a significant portion of the total agricultural produce in India. They cover a wide cultivation area and contribute about 28 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). These crops account for 37 per cent of the total exports of agricultural commodities from India. SESSION 1: HORTICULTURE AND ITS IMPORTANCE The term horticulture is derived from two Latin words hortus, meaning ‘garden’, and cultura meaning ‘cultivation’. It refers to crops cultivated in an enclosure, i.e., garden cultivation. Chapter -1.indd 1 11-07-2018 11:33:32 NOTES Features and importance Horticulture crops perform a vital role in the Indian economy by generating employment, providing raw material to various food processing industries, and higher farm profitability due to higher production and export earnings from foreign exchange. (a) Horticulture crops are a source of variability in farm produce and diets. (b) They are a source of nutrients, vitamins, minerals, flavour, aroma, dietary fibres, etc. (c) They contain health benefiting compounds and medicines. (d) These crops have aesthetic value and protect the environment. -

Botany and Horticulture

Voices from the Past Botany and Horticulture By Kim Black Tape #42 Oral interview conducted by Harold Forbush Transcribed by Theophilus E. Tandoh October 2004 Brigham Young University-Idaho 2 HF: Coming to his office here in the plant science building, for the purpose of making this early morning interview. It is about 7:00 am and Bishop Black with all of his other duties has agreed to share enough so with the interviewer Harold Forbush here on Ricks College campus. Dr. Black would you be so kind as to give me the place of the birth year, your background before you came to Ricks college. KB: I was born June 10th 1937 in Ricks Field, Utah in Southeastern Utah, grew up on a cattle range in Wayne County in Tory. Father has been a Range all his life and I am the youngest of six children. Graduated from Wayne High School, attended Dixie College in St. George for 2 years went on a mission for the Mormon Church to the Gulf State. Returned and went to Utah State where I got my bachelors degree in Agricultural Education. The conclusion of my Bachelors Degree, I was awarded a scholarship to go on to graduate work but I’d like to take a job in the Jordan School District teaching Vocational Agriculture and Botany. While there I continued my education got a Masters Degree at the University of South Dakota during the summers and 1967 came to Ricks College after being here three years took a leave of absence and went back for my doctorates at Oregon State University in Horticulture with emphasis on Physiology. -

Wood Ash in the Garden Page 1 of 2

Wood Ash in the Garden Page 1 of 2 Purdue University Consumer Horticulture Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Home / About / New / Wood Ash in the Garden Released 16 November 2000 by B. Rosie Lerner, Extension Consumer Horticulture Specialist Wood stoves and fireplaces are great for warming gardeners' chilly hands and feet, but what are we to do with the resulting ashes? Many gardening books advise throwing these ashes in the garden. Wood ash does have fertilizer value, the amount varying somewhat with the species of wood being used. Generally, wood ash contains less than 10 percent potash, 1 percent phosphate and trace amounts of micro-nutrients such as iron, manganese, boron, copper and zinc. Trace amounts of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, nickel and chromium also may be present. Wood ash does not contain nitrogen. The largest component of wood ash (about 25 percent) is calcium carbonate, a common liming material that increases soil alkalinity. Wood ash has a very fine particle size, so it reacts rapidly and completely in the soil. Although small amounts of nutrients are applied with wood ash, the main effect is that of a liming agent. Increasing the alkalinity of the soil does affect plant nutrition. Nutrients are most readily available to plants when the soil is slightly acidic. As soil alkalinity increases and the pH rises above 7.0, nutrients such as phosphorus, iron, boron, manganese, copper, zinc and potassium become chemically tied to the soil and less available for plant use. Applying small amounts of wood ash to most soils will not adversely affect your garden crops, and the ash does help replenish some nutrients. -

Agriculture, Forestry, Horticulture, Pre-Veterinarian Medicine Baccalaureate Transfer Program at Danville Area Community College

Agriculture, Forestry, Horticulture, Pre-Veterinarian Medicine Baccalaureate Transfer Program at Danville Area Community College. Students can complete the first two years (approximately 60 credit hours) of a bachelor’s degree at Danville Area Community College. Typically, the first two years of a bachelor’s degree consist of general education courses, the last two years are dedicated to major-specific coursework. Senior institutions do have various degree requirements. Therefore, it is necessary for transfer students to meet with an academic advisor or counselor when registering. Transfer students must also know their major and where they plan to transfer. Tuition Savings: Transfer students can save $10,000 or more by starting their bachelor’s degree at DACC. The estimated expenses for one year, including housing where applicable, is $2,900 at DACC and any- where from $12,000-$29,000 at other public and private colleges/ universities in Illinois. Job/Employment Information: Positions You are Trained for: Park Ranger, Landscaper (artist), Veterinarian, Vet Technician, Ag Marketing, Seed Salesman, Market Traders, to name a few. For the most current salary information visit www.ilworkinfo.com. STEPS TO REGISTER: 1. Application 2. Placement Test 3. Register WAYS TO PAY: 1. Pay in full with cash, check, Visa or MasterCard 2. Student Financial Aid. Eligibility must be determined by payment due date. 3. FACTS Payment Plan. (Interest Free!) 4. Apply for Athletic and/or Academic Scholarships. 5. Employer paid or other third party payment such as JTP, TAA, etc. PROGRAM SPECIFIC COURSES: Check out the DACC website under www.dacc.edu to find out what specific courses you will be taking for this pro- gram of study. -

Creating a Forest Garden Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops

Creating a Forest Garden Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops Martin Crawford Contents Foreword by Rob Hopkins 15. Ground cover and herbaceous perennial species Introduction 16. Designing the ground cover / perennial layer 17. Annuals, biennials and climbers Part 1: How forest gardens work 18. Designing with annuals, biennials and climbers 1. Forest gardens Part 3: Extra design elements and maintenance 2. Forest garden features and products 3. The effects of climate change 19. Clearings 4. Natives and exotics 20. Paths 5. Emulating forest conditions 21. Fungi in forest gardens 6. Fertility in forest gardens 22. Harvesting and preserving 23. Maintenance Part 2: Designing your forest garden 24. Ongoing tasks 7. Ground preparation and planting Glossary 8. Growing your own plants 9. First design steps Appendix 1: Propagation tables 10. Designing wind protection Appendix 2: Species for windbreak hedges 11. Canopy species Appendix 3: Plants to attract beneficial insects and bees 12. Designing the canopy layer Appendix 4: Edible crops calendar 13. Shrub species 14. Designing the shrub layer Resources: Useful organisations, suppliers & publications Foreword In 1992, in the middle of my Permaculture Design Course, about 12 of us hopped on a bus for a day trip to Robert Hart’s forest garden, at Wenlock Edge in Shropshire. A forest garden tour with Robert Hart was like a tour of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory with Mr Wonka himself. “Look at this!”, “Try one of these!”. There was something extraordinary about this garden. As you walked around it, an awareness dawned that what surrounded you was more than just a garden – it was like the garden that Alice in Alice in Wonderland can only see through the door she is too small to get through: a tangible taste of something altogether new and wonderful yet also instinctively familiar. -

FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES

FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2010 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2010 iii Contents Foreword iv Contributors vi Acronyms ix Part 1. THE SCIENCE OF GENETIC MODIFICATION IN FOREST TREES 1. Genetic modification as a component of forest biotechnology 3 C. -

Major Diseases of Horticultural Crops and Their Management

Major Diseases of Horticultural Crops and this Management Dr.G. Thiribhuvanamala, Dr.S.Nakkeeran and Dr. K.Eraivan Arutkani Aiyanathan Department of Plant Pathology Centre for Plant Protection Studies Tamil Nadu Agricultural University Coimbatore – 641 003 Introduction: The Horticulture (fruits including nuts, vegetables including potato, tuber crops, mushroom, ornamental plants including cut flowers, spices, plantation crops and medicinal and aromatic plants) has become a key drivers for economic development in many of the states in the country and it contributes 30.4 per cent to GDP of agriculture, which calls for knowledge and technical backstopping. Intensive cultivation of the high valued horticultural crops, resulted in the outbreak of several diseases of National importance. In recent days, stakeholders import planting materials from North American Countries. Introduction of planting materials also impose threat in the introduction of new diseases not known to be present earlier. However, the diseases, if not managed on a war foot, it will result in drrastic yield reduction and quality of the produces. Hence adoption of suitable management measures with low residue levels in the final produces becomes as a need of the hour. In this regard, this paper gives emphasis on the diagnosis of plant diseases and their management. 293 Diseases of Mango and their management 1. Anthracnose :Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Anthracnose symptoms occur on leaves, twigs, petioles, flower clusters (panicles), and fruits. The incidence of this disease can reach almost 100% in fruit produced under wet or very humid conditions. On leaves, lesions start as small, angular, brown to black spots and later enlarge to form extensive dead areas. -

Horticulture Crop Plant Physiology Syllabus

Horticulture Crop Plant Physiology Syllabus This course provides students with a background into the physiological processes of plants with an emphasis on horticultural crops and how the processes relate to horticultural crop production practices. Among the topics covered are photosynthesis, respiration, water relations and morphogenesis. This course is an ACCEPtS course offered online to students at the University of Arkansas, Louisiana State University, Mississippi State University and Oklahoma State University. This course is available through any of the participating universities. Primary Instructors: Dr. Jeff Kuehny 225 J.C. Miller Hall Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, LA 70803 E-mail: [email protected] Phone:225-578-1043 Dr. Don LaBonte 131 J.C. Miller Hall Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, LA 70803 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 225-578-1024 Office Hours: Drs. Kuehny and La Bonte are available by appointment. Appointments should be scheduled via telephone or email as listed above. Prerequisites: Principles of Horticulture and first semester college chemistry (or equivalents) Credits: You will receive 3 semester credits for this course. Course Objectives: Upon completion of this course, students should have: 1. Developed an understanding the basic principles of plant cells and cellular metabolism. 2. Developed an understanding of water relations, mineral nutrition, ion transport, phloem transport, and how these physiological factors interact with the environment and the related crop response. 3. Developed an understanding of respiratory pathways and photosynthetic processes in relation to crop yield and the manipulation of plant growth regulators, herbicides and environmental factors affecting these processes. 4. Developed knowledge of plant growth and development to the production and scheduling of agricultural crops. -

Department of Plant and Soil Science Major: Horticulture - Floriculture & Ornamentals (FLOR) - 122

Department of Plant and Soil Science Major: Horticulture - Floriculture & Ornamentals (FLOR) - 122 Freshman Year Fall Semester (16 hours) Spring Semester (16 hours) AEC 2713 Intro to Food & Res Econ OR 3 BIO 1134 Biology I 4 EC 2113 Prin Macroeconomics OR CH 1053 Survey of Chemistry II OR 3 EC 2123 Prin Microeconomics CH 1223 Chemistry II CH 1043 Survey of Chemistry OR 3 CH 1051 Experimental Chemistry OR 1 CH 1213 Chemistry I CH 1121 Invst in Chemistry EN 1103 English Comp I 3 EN 1113 English Comp II 3 MA 1313 College Algebra 3 ST 2113 Intro to Stats OR 3 PSS 2343 Floral Design OR 3 MA 2113 Intro to Stats LA 1803 Landsc Arch Apprec PSS 1313 Plant Science 3 15 17 Sophomore Year Fall Semester (16 hours) Spring Semester (17 hours) BIO 1144 Biology II or 3 PSS 3301 Soils Laboratory 1 BIO 2113 Plant Biology PSS 3303 Soils 3 PSS 2423 Plant Materials I 3 PSS 3473 Plant Materials II 3 EPP 4113 Princ of Plant Pathology 3 FLS 1123 Spanish II 3 FLS 1113 Spanish I 3 CH 2501 Elem Organic Chemistry Lab 1 CO 1003 Fund of Public Speaking OR 3 CH 2503 Elem Organic Chemistry 3 CO 1013 Intro to Communications TKT 1273 Computer Applications OR 2 BIS 1012 Intro Bus Info Sys OR AIS 4203 Appl Comp Tec AIS ED 15 16 Summer Semester PSS 3433 Horticulture Internship 3 Junior Year Fall Semester (13 hours) Spring Semeste (13 hours) PSS 4341 Controlled Environ Ag Lab 1 PSS 3923 Plant Propagation 3 PSS 4343 Controlled Environ Ag 3 ACC 2213 Princ of Financial Acct 3 PO 3103 Genetics 3 PSS 3313 Interior PlantDes&Maint 3 EPP 3423 Ornamental Turf Insects OR 3 PSS 4363 -

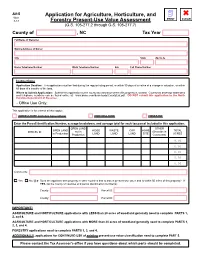

Application for Agriculture, Horticulture, and Forestry Present-Use Value

AV-5 Application for Agriculture, Horticulture, and Web 3-13 Forestry Present-Use Value Assessment (G.S. 105-277.2 through G.S. 105-277.7) County of , NC Tax Year Full Name of Owner(s) Mailing Address of Owner City State Zip Code Home Telephone Number Work Telephone Number Ext. Cell Phone Number Instructions Application Deadline: This application must be filed during the regular listing period, or within 30 days of a notice of a change in valuation, or within 60 days of a transfer of the land. Where to Submit Application: Submit this application to the county tax assessor where this property is located. County tax assessor addresses and telephone numbers can be found online at: www.dornc.com/downloads/CountyList.pdf. DO NOT submit this application to the North Carolina Department of Revenue. - Office Use Only: This application is for: (check all that apply) AGRICULTURE (includes Aquaculture) HORTICULTURE FORESTRY Enter the Parcel Identification Number, acreage breakdown, and acreage total for each tax parcel included in this application: OPEN LAND OTHER OPEN LAND WOOD WASTE CRP HOME TOTAL PARCEL ID not in (Describe in in Production Production LAND LAND LAND SITE Comments) ACRES Comments: Yes No ► Does the applicant own property in other counties that is also in present-use value and is within 50 miles of this property? If YES, list the county or counties and parcel identification number(s): County: Parcel ID: County: Parcel ID: IMPORTANT! AGRICULTURE and HORTICULTURE applications with LESS than 20 acres of woodland generally need to complete PARTS 1, 2, and 4.