Exploration of Effective Communication Strategies to Encourage People to Eat Less Meat in Order to Address Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Sustainability: a Comparison of Case Studies in UK, USA and Australia

17th Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Gold Coast, 16-19 Jan 2011 Social Sustainability: A Comparison of Case Studies in UK, USA and Australia Michael Y MAK and Clinton J PEACOCK School of Architecture and Built Environment The University of Newcastle, Australia Abstract Traditionally, the sustainable development concept emphasizes on environmental areas such as waste and recycling, energy efficiency, water resource, building design, carbon emission, and aims to eliminate negative environmental impact while continuing to be completely ecologically sustainable through skilful and sensitive design. However, contemporarily sustainable development also implies an improvement in the quality of life through education, justice, community participation, and recreation. Recently social sustainability has gained an increased awareness as a fundamental component of sustainable development to encompass human rights, labour rights, and corporate governance. The goals of social sustainability are that future generations should have the same or greater access to social resources as the current generation. This paper aims to reveal the level of focus a development has in meeting social sustainable goals, success factors for a development, and planning a development now and into the future from a socially orientated perspective. This paper examines the characteristics of social sustainable developments through the comparison of three case studies: the Thames Gateway in east of London, UK, the Sonoma Mountain Village in north of San Francisco, -

Summary of the Report : Onboard Employment Socio-Economic Impact of a Sustainable Fisheries Model

Summary of the report : Onboard employment Socio-economic impact of a sustainable fisheries model. greenpeace.es Index Introduction 3 Methodology 5 Sustainable fisheries model 7 Supporting low scale sustainable fisheries Phasing out of destructive fishing technique Extending the network of marine reserves Moving towards converting deep sea fishing to sustainability Limiting aquaculture operations Developing measures to inform and raise awareness in consumers Complying with biological optimums Controlling pollution in coastal areas Main Results: 13 Global impact on the economy and jobs Impact of the model by sectors of activity Reversing the job loss trend of the current fisheries model Characteristics of employment in fishing communities and the rest of the economy. Type of jobs created in the economy as a whole Conclusions Greenpeace Demands 22 Glossary 24 2 ONBOARD EMPLOYMENT. Introduction European fisheries are facing an The new Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) The reportOnboard employment: unsustainable situation in which regulation approved in May 2013 and Socio-economic impact of a sustainable previously rich, diverse fish effective from January 1st 2014, offers fisheries model proposes a series of the chance to eliminate overfishing measures to be implemented between populations have been decimated and provide an economically viable and 2014 and 2024 and analyses the effects to a fraction of their original size, environmentally sustainable option for they would have on the economy and giving rise to an ecological, social fishermen -

Assessing the Social Sustainability of Supply Chains Using Best Worst Method

Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method Hadi Badri Ahmadi (Corresponding author) School of Management Science and Engineering Dalian University of Technology No. 2 Linggong Road, Ganjingzi District Dalian Liaoning Province (116023), P.R of China E-mail: [email protected] Simonov Kusi-Sarpong School of Management Science and Engineering Dalian University of Technology No. 2 Linggong Road, Ganjingzi District Dalian Liaoning Province (116023), P.R of China Eco-Engineering and Management Consult Limited 409 Abafum Avenue TI’s - Adentan, Accra-Ghana E-mail: [email protected] Jafar Rezaei Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management Delft University of Technology 2628 BX Delft, the Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] 1 Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method Abstract – A truly sustainable organization needs to take the economic, environmental and social dimensions of sustainability into account. Although the economic and environmental dimensions of sustainability have been examined by many scholars and practitioners, thus far, the social dimension has been received less attention in literature and in practice, in particular in developing countries. Social sustainability enables other sustainability initiatives and overlooking this dimension can have a serious adverse impact across supply chains. To address this issue, this study proposes a framework for investigating the social sustainability of supply chains in manufacturing companies. To show the applicability and efficiency of the proposed framework, a sample of 38 experts was used to evaluate and prioritize social sustainability criteria, using a multi-criteria decision-making method called the ‘best worst method’ (BWM). The criteria are ranked according to their average weight obtained through BWM. -

(ESG) Update Supporting Sustainable Growth April 2018 2 Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Update HSBC Holdings Plc

HSBC Holdings plc Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Update Supporting sustainable growth April 2018 2 Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Update HSBC Holdings plc Hong Kong Stock Code: 5 HSBC Holdings plc Incorporated in England on 1 January 1959 with limited liability under the UK Companies Act Registered in England: number 617987 Our cover image The Singapore Supertrees are a cluster of large tree-like structures constructed in the heart of Singapore. Many of the Supertrees are embedded with environmentally sustainable functions – including generating solar energy, collecting rainwater, and acting as vertical gardens with more than 150,000 plants. These innovative structures create a green respite in the centre of the urban centre. Our photo competition winners The cover of this report showcases one of the images taken by one of our employees. The image was selected from more than 2,100 submissions to a Group-wide photography competition. Launched in June 2017, HSBC NOW Photo is an ongoing project that encourages our people to capture and share the diverse world around them with a camera. Contents 3 Contents 1 Group Chief Executive’s statement 5 2 Customers 8 3 Employees 21 4 Supporting sustainable growth 28 5 Governance 37 6 Links and information 41 4 Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Update HSBC Holdings plc About The information set out in this document, taken together with the information relating to ESG issues detailed in our HSBC Holdings plc Annual Report and Accounts 2017 and the information available in the links below, aims to provide you with key ESG information and data relevant to our operations for the year ended 31 December 2017 and in order to comply with the Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting Guide contained in Appendix 27 to The Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (‘ESG Guide’). -

Assessing the Role of Carbon Dioxide Removal in Companies' Climate

Net Expectations Assessing the role of carbon dioxide removal in companies’ climate plans. Briefing by Greenpeace UK January 2021 ~ While a few companies plan to deliver CDR Executive in specific projects, many plan to simply purchase credits on carbon markets, summary which have been beset with integrity problems and dubious accounting, even where certified. To stabilise global temperatures at any level – whether 1.5˚C, 2˚C, 3˚C or 5˚C Limits and uncertainties – carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions must The IPCC warns that reliance on CDR is a major reach net zero at some point, because risk to humanity’s ability to achieve the Paris goals. of CO2’s long-term, cumulative effect. The uncertainties are not whether mechanisms to remove CO2 “work”: they all work in a laboratory According to the Intergovernmental at least. Rather, it is whether they can be delivered Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), at scale, with sufficient funding and regulation, to store CO2 over the long term without unacceptable limiting warming to 1.5˚C requires net- social and environmental impacts. zero CO2 to be reached by about 2050. To illustrate the need for regulation, the carbon A small proportion of emissions is likely to be dioxide captured by forests is highly dependent on unavoidable and must be offset by carbon dioxide their specific circumstances, including their removal (CDR), such as by tree-planting (afforestation/ species diversity, the prior land use, and future reforestation) or by technological approaches like risks to the forest (such as fires or pests). In some bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) cases, forests and BECCS can increase rather than or direct air carbon capture with storage (DACCS). -

Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability

Eleventh International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability 21–23 JANUARY 2015 | SCANDIC HOTEL COPENHAGEN COPENHAGEN, DENMARK | ONSUSTAINABILITY.COM Sustainability Conference 1 Dear Delegate, The Sustainability knowledge community is an international conference, a cross-disciplinary scholarly journal, a book imprint, and an online knowledge community which, together, set out to describe, analyze and interpret the role of Sustainability. These media are intended to provide spaces for careful, scholarly reflection and open dialogue. The bases of this endeavour are cross- disciplinary. The community is brought together by a common concern for sustainability in an holistic perspective, where environmental, cultural, economic and, social concerns intersect. In addition to organizing the Sustainability Conference, Common Ground publishes papers from the conference at http://onsustainability.com/publications/journal. We do encourage all conference participants to submit an article based on their conference presentation for peer review and possible publication in the journal. We also publish books at http://onsustainability.com/publications/books, in both print and electronic formats. We would like to invite conference participants to develop publishing proposals for original works or for edited collections of papers drawn from the journal which address an identified theme. Finally, please join our online conversation by subscribing to our monthly email newsletter, and subscribe to our Facebook, RSS, or Twitter feeds at http://onsustainability.com. Common Ground also organizes conferences and publishes journals in other areas of critical intellectual human concern, including diversity, museums, technology, humanities and the arts, to name several (see http://commongroundpublishing.com). Our aim is to create new forms of knowledge community, where people meet in person and also remain connected virtually, making the most of the potentials for access using digital media. -

HRM's Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability

EPG SHRM Foundation’s Effective Practice Guidelines Series HRM’s Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability Produced in partnership with the World Federation of People Management Associations (WFPMA) and the North American Human Resource Management Association (NAHRMA) HRM’s Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM®). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2012 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. Selection of report topics, treatment of issues, interpretation and other editorial decisions for the Effective Practice Guidelines series are handled by SHRM Foundation staff and the report authors. -

Ecovillages and Permaculture: a Reference Model for Sustainable Consumption?

Ecovillages and Permaculture: a Reference Model for Sustainable Consumption? Autoria: Paulo Ricardo Zilio Abdala, Gabriel de Macedo Pereyron Mocellin Abstract Ecovillages are intentional ecological communities based on the harmless integration of human activities into the environment (Van Schyndel Kasper, 2008). The inspiration for this lifestyle comes from a concept called Permaculture, a term coined in 1978 by Bill Mollison, an Australian ecologist, and one of his students, David Holmgren, as a contraction of "permanent agriculture" or "permanent culture” (Mollison & Holmgren, 1978). In this research, we approach the theme of permaculture and ecovillages, focusing on ecovillagers ideas regarding sustainable consumption. Our intention is to present how people immersed in sustainable communities lifestyle deal with consumption issues by using different strategies and behaviors that are less harmful for the environment and the future generations. To accomplish this research, the sample was constituted of two ecovillages located in the south of Brazil. Both places were visited for a weekend each, during which we participated in the communities activities. Hence, the research has a qualitative methodology, best described as a short participant observation. Data collection includes field notes of the researchers, institutions website contents, as well as 4 hours of filmed interviews with a total of 7 subjects. The complexity of the phenomenon presents itself in the richness of the raw data collected. We consider this article a kind of working paper in broad terms, in the sense that new studies with more triangulation and further data collection are needed to extend the comprehension of the topic and to answer the additional questions this study brought. -

![Social Sustainability 2018]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3291/social-sustainability-2018-1733291.webp)

Social Sustainability 2018]

Social and Sustainability Science in ASEAN International Conference 2018 Agri-Food Systems, Rural Sustainability and Socioeconomic Transformations in South-east Asia 23-25 January 2018 Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, THAILAND #SocialSustainability #Chula100 #GreenAg Editor Sue Vize Editorial Staffs Andrew Noble Wayne Nelles Cholnapa Anukul Sayamol Charoenratana Sarinya Kitticharoenkan Cover Photo Siriporn Charoenratana Cover Design Waratrat LimJakkapob Copyright © 2018 Social and Sustainability Science in ASEAN International Conference 2018 Table of Contents Introduction Welcome Messages Surichai Wun’gaeo Chulalongkorn University 6 Sue Vize, UNESCO Bangkok 7 Program Committee 8 Introduction 9 Program Structure Schedule Day By Day 12 Sessions Details Keynotes 14 Plenary Policy Dialogue Sessions 15 Parallel Sessions 20 Post-Conference 31 Abstracts 33 General Information Registration 57 Venue 57 Local Information 60 Maps and Transportation 62 23-25 January 2018 [SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY 2018] Welcome address Surichai Wun’gaeo, Chulalongkorn University The first 18 years of the 21st century has been exceptionally remarkable as we, as humanity, have been faced with increasingly difficult and complex challenges. The solutions and alternatives are ways ahead, but collaboration and most importantly, shared values and vision are needed. The most significant shared value now is concerns on “sustainability”. As the oldest higher education institute in Thailand, Chulalongkorn University has brought the agenda of sustainability into our research, -

Anti-Consumption and Consumer Wellbeing

International Centre for Anti-consumption Research (ICAR) ANTI-CONSUMPTION AND CONSUMER WELLBEING July 4-5, 2014 Kiel, Germany ICAR Proceedings Organisers: Michael SW Lee, Stefan Hoffmann Published by Kiel University Christian-Albrechts-Platz 4, 24118 Kiel, Germany ISBN: 978-0-473-28933-1 Table of Contents Anti-Consumption in the Sailing City ....................................................................................................... 2 The History of Boycott Movements in Germany: Restrictions and Promotion of Consumer Well-being............................................................................. 4 The Multi-Facets of Sustainable Consumption, Anti-Consumption, Emotional Attachment and Consumer Well-Being: The Case of the Egyptian Food Industry ........................................................... 10 Applying Rhetorical Analysis to Investigating Counter-Ideological Resistance to Environmentalism .. 15 The Curious Case of Innovators Who Simultaneously Resist Giving Up Paper Bills .............................. 21 Navigating Between Folk Models of Consumer Well-Being: The Nutella Palm Oil Case ..................... 26 The Informational and Psychological Challenges of Converting to a Frugal Life .................................. 31 Motivations, Values, and Feelings behind Resistance to Consumption and Veganism ........................ 37 Shelving a Dominating Myth: A Study on Social Nudism and Material Absence ................................. 42 Education for Sustainable (Non-) Consumption through Mindfulness Training? -

Sustainability Transitions in Local Communities 1

Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation No. S 11/2018 Köhler, J.; Hohmann, C.; Dütschke, E. Sustainability transitions in local commu- nities: district heating, water systems and communal housing projects Werkstattbericht Nr. 9 in the TRANSNIK project With the support of Ulrike Hacke, Norman Laws, Kornelia Müller, Jutta Niederste-Hollenberg, Ina Renz, Elna Schirrmeister, Julius Wesche and Rubina Zern Acknowledgements This work was funded by the BMBF (German Federal Ministry of Education and Research) through the TRANSNIK project (funding reference 01UT1417A-C). Abstract Sustainability transitions take place across geographical and political levels. Ser- vices such as energy supply, water supply and wastewater management or hous- ing are part of daily life have to be provided at the district level within larger urban governance structures or by smaller rural administrations. However, relatively lit- tle attention has been given to the analysis of these local structures. This paper reviews case studies of niches in the areas of district heat networks, communal housing projects for the elderly and sustainable water/wastewater management. The paper addresses the following research questions: 1. What are the similarities and differences in the case study's drivers and barriers that have arisen between the fields of action and what conclusions can be drawn from these insights in order to maximize success factors or to minimize obstacles in advance? 2. What are the key factors for transition, also with regard to the synergies of the three fields of action? 3. What is the stage of development of the niches? Are they in a transition process or not? District heat networks are established as a niche, but given the current policy and financial environment are developing very slowly. -

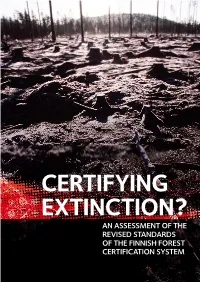

An Assessment of the Revised Standards of the Finnish Forest Certification System 2

CERTIFYING EXTINCTION ? AN ASSESSMENT OF THE REVISED STANDARDS OF THE FINNISH FOREST CERTIFICATION SYSTEM 2 CopyrightCopyright © GrGreenpeaceeenpeace SeptSeptemberember 20020044 ISBN: 1 903 90709 8 WWrittenritten by Sini HarHarkkikki PhoPhotographictographic crcreditsedits FFrontront ccoverover ©W©Weiner/Greenpeaceeiner/Greenpeace This page ©Liimat©Liimatainen/ainen/Greenpeace PPageage ii ©Liimatainen/Greenpeace PPageage 1 ©W©Weckenmann/Greenpeaceeckenmann/Greenpeace PagePage 2 ©Leinonen/Greenpeace©Leinonen/Greenpeace PagePage 4–5 ©Harkki/Greenpeace©Harkki/Greenpeace PagePage 7 ©Snellman/Greenpeace PagePage 8 ©Leinonen/Greenpeace©Leinonen/Greenpeace PagePage 10 ©Leinonen/Greenpeace©Leinonen/Greenpeace PagePage 13 ©Tuomela/Greenpeace PagePage 1155 ©Hölttä/Greenpeace PagePage 16 ©Leinonen/Greenpeace PagePage 1717 ©Liimatainen/Greenpeace PagePage 18 ©Leinonen/Greenpeace©Leinonen/Greenpeace PagePage 1919 ©Weckenmann/Greenpeace PagePage 20 ©Leinonen/Greenpeace©Leinonen/Greenpeace This used to be an important reindeer PagePage 2121 ©L©Leinonen/Greenpeaceeinonen/Greenpeace grazing forest. Areas of old-growth forest, Inside back ©Leinonen/Greenpeace©Leinonen/Greenpeace like this one in Inari (Sámi region), have been Back covercover ©L©Leinonen/Greenpeaceeinonen/Greenpeace logged by the Finnish Government’s logging arm, Metsähallitus, under the Finnish Forest Designed by PPaulaul HamiltonHamilton and PPetereter MMauderauder @ oneoneanotheranother Certification System. CERTIFYING EXTINCTION? AN ASSESSMENT OF THE REVISED STANDARDS OF THE FINNISH FOREST CERTIFICATION SYSTEM i FOREWORD Finland’s forests are among the most intensively managed in the world. Over 50 million cubic metres of wood are harvested every year from the country’s 20 million hectares of commercial forests. The Finnish forest management model has resulted in the rapid conversion of natural forests into monotonous industrial forests that lack many key features of boreal forest ecosystems. Forestry is the most serious threat to species survival in Finland.