Nothing Is As It Seems: Reading Deviance in Faulkner's Sanctuary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JMP Securities Elite 80 Report (Formerly Super 70)

Cybersecurity, Data Management & ,7 Infrastructure FEBRUARY 201 ELITE 80 THE HOTTEST PRIVATELY HELD &<%(5SECURITY, '$7$0$1$*(0(17 AND ,7,1)5$6758&785( COMPANIES &RS\ULJKWWLWLSRQJSZO6KXWWHUVWRFNFRP Erik Suppiger Patrick Walravens Michael Berg [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (415) 835-3918 (415) 835-8943 (415)-835-3914 FOR DISCLOSURE AND FOOTNOTE INFORMATION, REFER TO JMP FACTS AND DISCLOSURES SECTION. Cybersecurity, Data Management & IT Infrastructure TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 Top Trends and Technological Changes ............................................................................................ 5 Funding Trends ................................................................................................................................ 11 Index by Venture Capital Firm .......................................................................................................... 17 Actifio ................................................................................................................................................ 22 Alert Logic ......................................................................................................................................... 23 AlgoSec ............................................................................................................................................ 24 AnchorFree ...................................................................................................................................... -

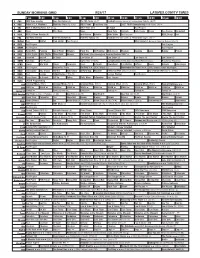

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Super! Drama TV November 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 11Th and the 24Th

Super! drama TV November 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 11th and the 24th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.11.01 Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 06:00 #2 「Witness」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 GENERATION Season 7 #5 07:30 07:30 「GAMBIT Part 2」 07:30 08:00 08:00 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 GENERATION Season 7 #6 08:30 08:30 「PHANTASMS」 08:30 09:00 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #19 「VICE」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 14 10:30 #12 「Hamelin」 11:00 11:00 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information[J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 12:00 #7 「Target Rich」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 13:00 #8 「Awake」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 14:00 #9 「Internal Affairs」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 15:00 #10 「Future Perfect」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 16:00 #11 「Entropy」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 17:00 #12 「Drive」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 18:00 #17 「BROTHERS」 18:30 18:30 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 MANIFEST Season 2 19:00 #2 「Grounded」 19:30 19:30 19:30 20:00 20:00 20:00 LOVE LIFE 20:00 #3 「Danny Two Phones」 20:30 20:30 20:30 20:45 information[J] 21:00 21:00 21:00 S.W.A.T. -

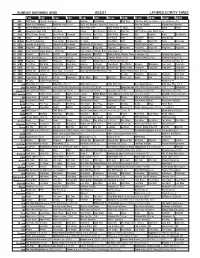

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

“I'm Looking for Jack Bauer at That Time”: 24, Torture

“I’M LOOKING FOR JACK BAUER AT THAT TIME”: 24, TORTURE, & GETTING YOUR HANDS DIRTY IN THE NAME OF IDEOLOGY By RYAN JAMES THOMAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY The Edward R. Murrow School of Communication MAY 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of RYAN JAMES THOMAS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ____________________________________ Chair ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank my committee chair, Dr. Elizabeth Blanks Hindman, for her advice, insight, dedication, and suggestions, all of which have helped shape this project into what it is today, not to mention keeping me on track with timely yet thorough feedback. I would also like to extend my sincere thanks to the rest of my committee, Dr. Susan Dente Ross, Dr. Michael Salvador, and Dr. Richard Taflinger. Each of them has offered interesting, considerate, and challenging feedback, and both this project and I are considerably richer as a result of their input. To my girlfriend, Alexandra Ford: thank you for your constant encouragement, support, and love. You have helped me meet deadlines, keep on track, stay focused, and remain positive. Perhaps most importantly, you make me smile. A lot. So thanks for that. You are an unending source of joy in my life. Finally, I wish also to thank my parents for all the encouragement they have given me from an early age to aspire to be all that I can be, instilling in me a love for books, education, and self-improvement that I have to this day. -

Maggie Siff Still Enjoys Handling 'Billions'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! May 1 - 7, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 S L P E I F W P S L Z A R V E Your Key 2 x 3" ad C Y K O Q Q U E N D O R E C N U B V C H U C K W L W Y N K A To Buying R N O L E N R C U E S A V I N and Selling! M D L B A W Y L H W N X T W J 2 x 3.5" ad B U K I B B E X L I C R H E T A C L L V Y W N M S K O I K S W L A S U A B O D U T M S E O A E P T W U D S B Y E Y I S G U N U O H C A P I T A L F K N C E V L B E G A B V U P F A E R M W L V K R B W G R F O W F “Billions” begins its G I A M A T T I R I V A L R Y fifth season Sunday D E Z E B I F A N R J K L F E on Showtime. -

Sunday Morning, March 31

SUNDAY MORNING, MARCH 31 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Easter Worship at the United Meth- This Week With George Stepha- Your Voice, Your Paid 2/KATU 2 2 odist Church nopoulos (N) (cc) (TVG) Vote CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) ATP Tennis Sony Open, Men’s Final. (N) (Live) (cc) 2013 NCAA Basketball Tournament 6/KOIN 6 6 Regional Final. NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) NHL Hockey Chicago at Detroit Red Wings. (N) (Live) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature River of No Return. Frank Oregon Experience Modoc War. 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Church River of No Return. (TVG) (TVG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Paid Paid Paid Paid Wicker Park ★★ (‘04) Josh Hart- 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) nett, Rose Byrne. ‘PG-13’ (1:54) Paid Paid David Jeremiah Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- David Jeremiah Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With Time for a 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (cc) Hagin (TVG) (cc) (TVG) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

Television Listings WHAS $ + at 6PM (N) News Tonight (N) Tion (N) Demons

B13 / T V LISTINGS The Oldham Era / Thursday, May 17, 2012 THURSDAY EVENING MAY 17, 2012 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 Wave 3 News NBC Nightly WAVE 3 News WAVE 3 News Community 30 Rock (Sea- Community Community (In Awake “Two Birds” Britten WAVE 3 News Tonight Show WAVE ^ # at 6 (N) News (N) at 7 (N) at 7:30 (N) son Finale) (N) (N) Stereo) learns the truth. (N) at 11 w/Jay Leno WHAS-11 Live ABC World Entertainment Inside Edi- Missing Becca faces her inner Grey’s Anatomy The doctors (:01) Scandal Quinn finds her- WHAS11 (:35) Nightline Television Listings WHAS $ + at 6PM (N) News Tonight (N) tion (N) demons. (In Stereo) face a dangerous situation. self in a bad situation. News at 11 (N) WLKY News CBS Evening Wheel of For- Jeopardy! (N) The Big Bang (:31) Rules of Person of Interest Reese be- The Mentalist Jane fails to WLKY News Late Show W/ May 17th - May 23rd, 2012 WLKY % @ at 6:00PM (N) News/Pelley tune (N) Theory Engagement comes trapped with his POI. defeat Red John. at 11:00PM Letterman TMZ (N) (In Cheaters (In The People’s Court (N) Perez Hilton All Access “Katy The Vampire Diaries Damon News on (:35) Inside It’s Always (:35) American THURSDAY, MAY 17, 2012 WBKI _ B Stereo) Stereo) Perry” (N) and Elena search for Stefan. WBKI Edition (N) Sunny Dad Judge Judy WDRB Local Two and a The Big Bang American Idol The finalists are Touch Martin gets involved WDRB News (:45) WDRB Two and a 30 Rock MORNING WDRB ) I Evening News Half Men Theory revealed. -

Word Search 'Hillary' – Her Side of the Story

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 28 - March 5, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H I M L E X Z V W Y N F M Your Key 2 x 3" ad O L J B F R E P S I M O N E I S P A G E R L O E J I A L R P To Buying I L N R N W I N J T J A B X O and Selling! M W I A J V Y E A S E G E L A 2 x 3.5" ad U U C N A C F R N A Y R N N C M J E T D S O U Q D A X J N S A Z C X D L J T H V S C A U M Hillary Clinton is the F O F R P F E J D E X H M Y O subject of “Hillary,” premiering next G E I X V R J Y A N I U I C E Friday on Hulu. U J E J U N E L K T D J N P V E S L Q W P R E D U I G E L S Y V D E F X J Y X R T Z A X O O F R E D W Y N N E A P J M N R D P Y M I U S E B E Y S N E “Dispatches from Elsewhere” on AMC Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Peter (Jason) Segel (Self) Exploration Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Janice (Sally) Field Game ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Simone (Eve) Lindley Jejune (Institute) Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Octavio (Coleman) (Richard E.) Grant Adventure County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Fredwynn (André) Benjamin (New) Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week ‘Hillary’ – Her side of the story 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

RED BANK Today "JW

Weather Distribution / F* tatfiy, (*** Mi tfr RED BANK Today "JW. ">H« «*•* ••, Urn toolgW, «. High tomorrow, mi<i-60s. see tides and weather 1 Independent Daily f 16,800 page 2. I MONDAY THKXJGHFRIDAY-EST. UTS I BY CARRIER VOL, 83, NO. 100 Issued Dally, Monday through Friday, entered ai Second Clisi Mattel RED BANK, N. J., MONDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 1960 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE at the Post Otflca at Red Bank. N. J.. under the Act of March 3. 1S79. 35c PER WEEK Pro-U.S. BuildLily-Tulip Group Plant in Spring Elected HOLMDEL — Construction o( a multi-million-dollar Lily-Tulip TOKYO (AP) - Japans pro- School Cup Corp. plant on Rt. 35 hers I. S. ruling conservatives rolled is scheduled to start in the iack to control of parliament to sprint;. ay but failed to get the all-out Walter J. Bergman, company lacking they had asked of the na- Quiet president, announced Saturday ion's voters. that grading and site preparation The conservatives claimed their work will start within two or 'ictory was a broad endorsement three weeks. if the U. S.-Japan security pact Prevails The company made a tentative and other close ties with the NEW ORLEANS (AP) — An announcement concerning its con- West. uncertain quiet prevailed ir. this struction plans Sept. 29. Their leftist opponents claimed rnuhled Deep South city today At that time, however, Mr. eftist gains proved just the op as it waited for a three-judge Bergman declined to give any posite. federal court to rule on school details, saying only that an of- - Same General Pattern integration. -

Super! Drama TV July 2020

Super! drama TV July 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance late at night on the 22th from 3:55 to 4:00 and the 29th from 3:55 to 4:00. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese (ET) Wed.1 Thu,2 Fri.3 Sat.4 Sun.5 (ET) 6:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 6:00 Season 4 Season 4 Season 4 Season 4 Season 4 #5 #6 #7 #8 #9 6:30 「INDISCRETION」 「REJOINED」 「LITTLE GREEN MEN」 「STARSHIP DOWN」 「THE SWORD OF KAHLESS」 6:30 7:00 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 THE CROSSING 7:00 #9 「SLINGSHOT」 #11 「SKYHOOK」 #13 「HEAVY METAL」 MYSTERONS #9 #15 「SEEK AND DESTROY」 「Hope Smiles from the Threshold」 7:30 07:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:30 JOE 90 7:30 #10 「TUNNELS OF TIME」 #12 「UNDER PRESSURE」 #14 「FALLING SKIES」 #15 「PROJECT 90」 8:00 08:00 SCORPION Season 4 08:00 SCORPION Season 4 08:00 SCORPION Season 4 08:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 08:00 THE CROSSING 8:00 #6 #7 #8 #15 「The Mystery of the Alluring Au Pair」 #10 「Queen Scary」 「Go With the Flo(Rence)」 「Faire Is Foul」 「The Androcles Option」 8:30 8:30 9:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 9:00 9:30 09:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 2 09:30 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 09:30 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. -

Entertainment &

CALENDAR DININGPUZZLES ENTERTAINMENT & June 6 -12, 2020 TV CARDINAL HEART AND VASCULAR PLLC Suriya Jayawardena MD. FACC. FSCAI Boards Certified Physician Heart Disease, Leg Pain due to poor circulation, Varicose Veins, Obesity, Erectile Dysfunction and Allergy clinic. All insurances accepted. Same week appointments. Friendly Staff. Testing done in the same office. Plan for Healthy Life Style 4380 Fayetteville Rd. • Lumberton, NC 28358 Tele: 919-718-0414 • Fax: 919-718-0280 • Hours of Operation: 8am-5pm Monday-Friday 2 Entertainment • TV Saturday, June 6, 2020 | Robesonian Page 2 — Saturday, June 6, 2020 — The Robesonian Rekindle the romance: ‘The Bachelor: The Greatest Seasons - Ever’ premieres on ABC By Kyla Brewer Bachelorette,” reliving memorable Each week, the host steps back unique premise. The show revolves Bachelor” and “The Bachelorette,” In the meantime, longtime TV Media moments, both good and bad. in time to look at one of his favorite around a single bachelor, and later Harrison treats fans to some virtual “Bachelor” host Harrison is offer- The first trailer for the new ABC seasons. It might be almost like bachelorette in “The Bachelorette,” check-ins with favorite alumni to ing viewers a walk down memory hen tensions are high, program dropped on May 11, and watching an entire “Bachelor” sea- which premiered in 2003. He or she find out how they’re doing after the lane. For those who may not be fa- Wthere’s nothing like indulg- it included some big promises for son in one night. The new ABC meets a variety of single women or final rose. miliar with the popular franchise, ing in some guilty pleasures, from the show’s 10-episode run.