Are Uk Supermarkets Socially Responsible? a Case Study Analysis of Labour Codes of Conduct in a Global Banana Supply Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Change: a Consideration of the UK Food Retail Industry, 1950-2010. Phd Thesis, Middlesex University

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Clough, Roger (2002) Retail change: a consideration of the UK food retail industry, 1950-2010. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/8105/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

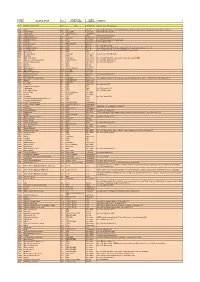

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

Blue Plaques Erected Since the Publication of This Book

Leeds Civic Trust Blue Plaques No Title Location Unveiler Date Sponsor 1 Burley Bar Stone Inside main entrance of Leeds Lord Marshall of Leeds, President of Leeds Civic 27 Nov ‘87 Leeds & Holbeck Building Society Building Society, The Headrow Trust, former Leader of Leeds City Council Leeds 1 2 Louis Le Prince British Waterways, Leeds Mr. William Le Prince Huettle, great-grandson 13 Oct ‘88 British Waterways Board Bridge, Lower Briggate, Leeds of Louis Le Prince (1st Plaque) 1 3 Louis Le Prince BBC Studios, Woodhouse Sir Richard Attenborough, Actor, Broadcaster 14 Oct ‘88 British Broadcasting Corporation Lane, Leeds 2 and Film Director (2nd Plaque) 4 Temple Mill Marshall Street, Leeds 11 Mr Bruce Taylor, Managing Director of Kay’s 14 Feb ‘89 Kay & Company Ltd 5 18 Park Place 18 Park Place, Leeds 1 Sir Christopher Benson, Chairman, MEPC plc 24 Feb ‘89 MEPC plc 6 The Victoria Hotel Great George Street, Leeds 1 Mr John Power MBE, Deputy Lord Lieutenant of 25 Apr ‘89 Joshua Tetley & Sons Ltd West Yorkshire 7 The Assembly Rooms Crown Street, Leeds 2 Mr Bettison (Senior) 27 Apr ‘89 Mr Bruce Bettison, then Owner of Waterloo Antiques 8 Kemplay’s Academy Nash’s Tudor Fish Restaurant, Mr. Lawrence Bellhouse, Proprietor, Nash’s May ‘89 Lawrence Bellhouse, Proprietor, Nash’s off New Briggate, Leeds 1 Tudor Fish Restaurant Tudor Fish Restaurant 9 Brodrick’s Buildings Cookridge Street, Leeds 2 Mr John M. Quinlan, Director, Trinity Services 20 Jul ‘89 Trinity Services (Developers) 10 The West Bar Bond Street Centre, Boar Councillor J.L. Carter, Lord Mayor of Leeds 19 Sept ‘89 Bond Street Shopping Centre Merchants’ Lane, Leeds 1 Association Page 1 of 14 No Title Location Unveiler Date Sponsor 11 Park Square 45 Park Square, Leeds 1 Mr. -

A STUDY of the EVOLUTION of CONCENTRATION in the FOOD DISTRIBUTION INDUSTRY for the UNITED KINGDOM October 1977

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF CONCENTRATION IN THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION INDUSTRY FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM October 1977 In 1970 the Commission initiated a research programme on the evolution of concen tration and com petition in several sectors and markets of manufacturing industries in the different Member States (textile, paper, pharmaceutical and photographic pro ducts, cycles and motorcycles, agricultural machinery, office machinery, textile machinery, civil engineering equipment, hoisting and handling equipment, electronic and audio equipment, radio and television receivers, domestic electrical appliances, food and drink manufacturing industries). The aims, criteria and principal results of this research are set out in the document "M ethodology of concentration analysis applied to the study o f industries and markets” , by Dr. Remo LINDA, (ref. 8756), September 1976. This particular volume constitutes a part of the second series of studies, the main aims of which is to present the results of the research on the evolution of concentration in the food distribution industry for the United Kingdom. Another volume, already published (vol. II: Price Surveys), outlines the results of the research on the distribution o f food products in the United Kingdom, w ith regard to the evolution of prices and mark-ups, based on a limited sample of food products and on a limited number of sales points in the Greater London area. Similar volumes concerning the structures of the distributive systems and the evolution of prices and mark ups have been established also fo r other Member States (Germany, France, Italy and Denmark). COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF CONCENTRATION IN THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION INDUSTRY FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM VOLUME I Industry structure and concentration by Development Analysts Ltd., 49 Lower Addiscombe Road, Croydon, CRO 6PQ, England. -

Download (11Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/98784 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 2 o Strategic Groups, Industry Structure and Firms ’ Strategies: Theory and Evidence from the UK Grocery Retailing Industry Francesco Fortunato Curto Thesis Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Warwick Business School University of Warwick England May 1998 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1.0 The Research P- 1 1.1 Structure of the Research P- 5 Chapter 2 The Theoretical Foundations of Strategic Groups: the Harvard Approach 2.0 Introduction P- 9 2.1 The Research Context: Industrial Organisation and the Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) Paradigm p. 10 2.1.1 Firms’ Strategies and the Industry Structure in the SCP Paradigm P- 15 2.2 The Theory of Strategic Groups and Mobility Barriers p. 16 2.2.1 Structural and Endogenous Barriers to Entry P- 18 2.2.2 Barriers to Mobility and Strategic Groups P- 20 2.2.3 The Origins of Strategic Groups and Firms’ Strategic Behaviour P- 21 2.2.4 Intergroup Mobility, New Entry and Mobility Dynamics p. 22 2.3 The Characteristics of Strategic Groups Theory P- 25 2.4 Further Theoretical Development: Porter’s (1979) Theory of a Firm’s Profitability P- 28 2.4.1 Oligopolistic Rivalry and Firms’ Performance p. -

A Case-Study of Kwik Save Group P.L.C

Spatial-Structural Relationships in Retail corporate Growth: A Case-Study of Kwik Save Group P.L.C. by Leigh Sparks* Retail companies develop and expand by combining both struc- tural attributes and spatial awareness. The spatial-structural development and growth of individual retail companies has been neglected in the growing retail literature. Through examin- ing in detail the growth and development of retail companies, concentrating on both the spatial and structural dimensions of development ad using the concepts and ideas emerging in cognate fields such as entrepreneurship, competitive strategy and innovation diffusion, it is postulated that a better under- standing of the complexities of retail growth will be produced. A case-study of Kwik Save Group P.L.C. is used here to explore these concepts, to build a spatial-structural theory of retail change and to demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of detailed study of individual firm. INTRODUCTION 'Every marketing strategy leaves a spatial imprint' [Jones and Simmons, 1987: 331.1. Retail companies operate in both a business and a spatial environment. It has often been claimed that location is crucial to retailing,, but it is equally true that the retail offering and operation has to fit both the marketing and the wider competitive environment. Retail businesses develop by considering both the spatial and the structural elements of the company and the environment. Retailers have to determine what and how they are going to retail, where outlets are to be located in respect of the market and the competition and how the retail operations are going to be organised. -

The Effect of Organizational Processes on the Strategy to Introduce New Technology Into Retailing

The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL PROCESSES ON THE STRATEGY TO INTRODUCE NEW TECHNOLOGY INTO RETAILING Submitted By CATHERINE J. CROMBLEHOLME in fulfilment of the requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy DURHAM UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL JULY 1988 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without her prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. .- 6 JUL 1989 ABSTRACT THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL PROCESSES ON THE STRATEGY TO INTRODUCE NEW TECHNOLOGY INTO RETAILING Despite the widespread changes that are taking place in retail technology, it is an area which 'has been subjected to relatively little research. In particular, there has been a neglect of the process of introducing new technology. Based on a comparative study of two supermarket chains, this thesis examines the way in which technology is introduced into retail companies and the problems they encounter. The technology in question consisted of the computerisation of all head office and warehouse systems and the introduction of Electronic Point of Sale (EPOS) and Portable Data Capture Units (PDCs) into the branches. Research methods included participant observation, interviews and analysis of documents. The study found that the introduction of new technology was not the result of a rational, pre-determined strategy, but that it evolved from a series of ad hoc decisions. Organizational processes played an important part in forming this emerging strategy and also influenced its successful implementation. -

Bejam LAST MONTH a Look Was Taken at Frozen Amazing—There Were Only 50,000 Domestic Their Local Sainsbury's

JQ JOURNAL ^J f^J April 1983 Page 4 «J3IJ'» ti.A Page 6 LI 'lillllillUlllHMJIIIilHHyil im HOMEBASE OPENINGS EWS NEWS NEWS 1 AN ADDITION to the Journal team this month is Yvonne Burke, who joins as assistant editor. „ Yvonne, 24, has moved to Blackfriars from the West End of London, where she was assistant editor of Selfridges' house magazine— The Key. Talented and vivacious, her interests, apart from writing, include aerobics, the theatre and travel. In case the name rings a bell, Yvonne already has a sister at JS—Colette, who is a buyer in the grocery division. Yvonne Burke JSJOURNAL Executive Club is published every month for employees of A TALK FROM Minister of Agriculture, nature, neither too detailed nor too J Sainsbury pic Fisheries and Food, the Rt Hon Peter specialised, and calls for decision making Stamford House Walker, brought the latest season of on such matters as size of production, Stamford Street Sainsbury's Executive Club to a successful product quality, pricing and marketing. London SE1 9LL close. Played in ten rounds, the winners will be Telephone: 01-921 6660 Peter Walker spoke of his experience the leading team at the end of the last Associate editor representing Britain in Common Market round, probably sometime in June. John Fielder discussions on agriculture and his views Assistant editor on the development of the Community's Competition Yvonne Burke food policy. Journal secretary Members of the club are also taking The competition was open to all Ann Grain part in a business game competition, with grades of management from JS Streat- Design a first prize of a case of JS champagne! ham and Blackfriars offices and Home- Alex Evans The competition takes the form of a base head office. -

ANMW Retail Multiple Classifications

ANMW ANMW RETAIL ANMW MULTIPLE GROUP Status COMMENTS CODE CLASSIFICATIONS CATEGORY AFS Amazon Fresh Stores Live CON Convenience Code live from 16th Jul 2021 ALD Aldi Live SUP Grocery Live 21st November 2011 - from 13th April 2015 - Class from MIS to SUP, Category from Other RMG to Grocery ALE Aleef Garages Live CFC / SER Forecourts Revived 7th February 2011 AFJ Alfred Jones Live CON/CCC/CFC Convenience AAS Alpha Airports Live ITP Travel Revived 28th August 2009 APW Appleby Westwood Live CON/CCC Convenience Live 1st February 2010 APL Applegreen Stores Live CFC Forecourts Live 29th November 2010 - Ireland Only ARA Aramark Live CAP Convenience Live 31st March 2008 ASP Asda Forecourts Live PFC/CFC/SER Grocery ASL Asda Living Live CAP Grocery Live 1st February 2010 ASN Asda Supermarkets Live CCC Grocery Live 29th November 2010 : Name updated from 7th Jan, previously ASDA - NETTO ASD Asda Superstores Live SUP Grocery Name updated from 7th Jan, previously ASDA - Supermarkets BAN Bailey News Live CTN CTN BES Bestways Retail Live CON/CCC Convenience Code live from 16th Mar 2020 BLK Blackwells Live MSN Other RMG TAT Blakemore Retail Live CON/CCC Convenience Live from 28th May 2012 - Just a name change previously TATES BRI Blakemore Retail Independents Live CON/CFC/PFC Convenience Live from 20th October 2014 BGC Blooms Garden Centres Live MIS Other RMG Live from 13th March 2017 BTH Booths Live SUP Grocery BOO Boots Plc Live MSN High Street BOU Bourne Leisure Live Refer to class list Other RMG BPC BP Connect Live CFC/SER Forecourts BPS BP M&S Simply -

On Competition Policy

EUROPEAN COAL AND STEEL COMMUNITY EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNIry EUROPEAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMUNITY coMMtsstoN Seventh Report on Competition Policy (Published in conjunction with the 'Eleventh General Report on the Activities of the European Communities') LUXEMBOURG April 1978 This publication is also available in the foliowing languages: DA |SBN 92-825-0031-4 DE ISBN 92-825-0032-2 FR |SBN 92-825-003F9 lT tsBN 92-825-0035-7 NL |SBN 92-825-0036-5 A bibliographical slip can be found at the end of this volume @ Copyright ECSC/EEC/EAEC, Brussels and Luxembourg, 1978 Pilnted in Belgium Reproduction authorized, in whole or in part, provided the sourco ls acknowledged ISBN 92-825-0033-0 Catalogue No: CB-24-77-237-EN-C Contents lnlroduc{lon PART ONE _ COMPETITION POLTCY TOWARDS ENTERPRISES 15 Chapter I : Maln devetopmenls In Communlty pollcy 17 S 1 - Price disparitie$ in the Community 17 g 2 - Information agreements 18 S 3 - Exclusive purchasing agreements 21 S 4 - Community-wide guarantee service 24 S 5 - Measures to assist small business 26 S 6 - Supply obligatlons ol undertakings in a dominant position 30 S 7 - Horizontal groups and economic entities 31 policy dumplng u S I - The Commission's on intra-Community S I Findings of the inquiry into the market for naphtha for petrochemical use and - into the behaviour of the oil companies 38 Cbapler tl : General rules applylng to flrms 53 S 1 - Amendment of existing regulations and notices 53 'f . Extension and amendment of Regulation (EEC) No 2779/72 (speclalization agreements) 53 2. Amendment of Regulation No 6/6/EEC (exclusive dealing agreements) 54 3. -

Value Travels – Tesco Is About Creating Value for Customers to Earn Their Lifetime Loyalty

www.tesco.com/annualreport09 Tesco PLC Tesco PLC Tesco House Delamare Road Cheshunt Hertfordshire EN8 9SL Value Annual Report and Financial Statements 2009 travels Annual Report and Financial Statements 2009 Introduction Financial highlights 2 Chairman’s statement 3 Printed on Revive, a 100% recycled Tesco at a glance 4 paper with FSC certification. Printed by CTD using an alcohol- Chief Executive’s Q&A 5 free process. The printing inks are made with non-hazardous vegetable oil from renewable Report of the Directors 6 sources. Over 90% of solvents and developers are recycled for further Business Review 6 use and recycling initiatives are in Long-term strategy 6 place for all other waste associated Markets served and business model 7 with this production. CTD are FSC International 8 and ISO 14001 certified with strict Core UK 12 procedures in place to safeguard the Non-food 16 environment through all processes. Retailing Services 20 Designed and produced by Community 24 35 Communications. People 28 Resources and relationships 30 Group performance 32 Key Performance Indicators 36 Risks and uncertainties 38 Financial review 40 General information 41 Our Board of Directors 42 Corporate governance 44 Directors’ remuneration report 50 Financial statements 65 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 66 Independent auditors’ report to the members of Tesco PLC 67 Group income statement 68 Group statement of recognised income and expense 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group cash flow statement 71 Reconciliation of net cash flow to movement in net debt note 71 Notes to the Group financial statements 72 Five year record 124 Tesco PLC – Parent Company financial statements 126 Independent auditors’ report to the members of Tesco PLC 136 Go online Go online Every year, more and more Every year, more and more information is available for information is available for our shareholders, staff and our shareholders, staff and customers online. -

A Consideratici! of the UK Food Retail Industry, 1950-2010. © Roger Clough 2002 Ph.D Middlesex University

Retail Change: a consideratici! of the UK food retail industry, 1950-2010. © Roger Clough 2002 Ph.D Middlesex University Abstract The immense changes to have taken place in UK food retailing during the second half of the 20th ccntury are detailed, explained and analysed, with constant référence to théories of retail change. The resuit is not just a history of UK food retail change post-1950, but a comprehensive évaluation and extension of retail change theory, with new driving forces and ideas elaborated, and a forecast of likely key developments to 2010. The thesis is based largely on the testimonies of key industry actors of the period, including past and présent executives of leading food retali organisations, and followed an un-structured interview approach, allowing stories to be told without unnecessary constraint. The development of the industry is detailed and explained, drawing heavily on thèse testìmonies, and this change is explained with référence to major factors with a direct hearing on the industry, such as government policy and socio-economie change. Because of the emphasis on witness accounts, the théories of retail change are analysed with a heavy focus on the people driving change, a refreshing change in a field where the historical nature of the subject tends to drive research towards secondary sources of data. The thesis contributes a better understanding of the forces driving the théories of retail change, and proposes an extension to the domain of application. The relevant éléments of the théories of retail change are implemented to forecast likely developments in the UK food retail industry to 2010, which is complemented by an 'expert' Delphi forecast and a projection of current socio-economie trends.