The Relationship Between the State and Workers' Unions and Its Impacts in the Union-Based Health Coverage Regime in Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

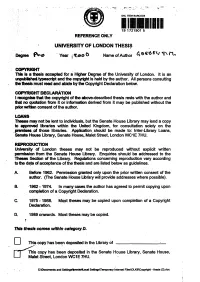

This Thesis Comes Within Category D

* SHL ITEM BARCODE 19 1721901 5 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year i ^Loo 0 Name of Author COPYRIGHT This Is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, it is an unpubfished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the .premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 -1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 -1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Victoria Basualdo∗∗

La participación de trabajadores y sindicalistas en la campaña internacional contra la última dictadura argentina∗ Victoria Basualdo∗∗ La historiografía sobre sindicatos y trabajadores durante la última dictadura argentina (1976-1983) realizó contribuciones valiosas, aunque ha dejado, sin embargo, un conjunto de temas importantes sin explorar1. Uno de ellos es el que se refiere a la acción de trabajadores y dirigentes sindicales en el exilio, que sólo ha comenzado a ser abordado muy recientemente2. Este trabajo tiene como objetivo analizar una trayectoria particularmente significativa del destierro de trabajadores y sindicalistas: la labor de denuncia internacional desarrollada por el dirigente gráfico Raimundo Ongaro durante su estadía en Perú, Francia y España entre 1975 y 1984, así como los orígenes, propósitos y contribuciones de dos organizaciones mediante las cuales este dirigente intentó dar forma orgánica a los esfuerzos de trabajadores y sindicalistas en el exilio: el Centro Sindical por los derechos de los trabajadores en Argentina y Latinoamérica (CS) y el colectivo de Trabajadores y Sindicalistas Argentinos en el Exilio (TYSAE). Raimundo Ongaro es recordado por su designación como Secretario General de la CGT de los Argentinos (CGTA) en 1968. El resto de su trayectoria sindical ha sido poco estudiada, y su figura escasamente reivindicada desde el campo de militancia sindical y de izquierda, a diferencia de lo sucedido con otros dirigentes, como Agustín Tosco, quien compartió con Ongaro posiciones de liderazgo en el campo del sindicalismo “combativo” desde fines de los años ‘60 a mediados de los ‘70. Nacido en 1925, Ongaro estudió artes gráficas y música en el Colegio “San Carlos de Don Bosco,” donde recibió además una formación cristiana que lo marcó profundamente durante toda su vida. -

Agustín Tosco En La Construcción De Un Nuevo

Agustín Tosco y la proyección de un nuevo modelo sindical: la polémica con José Rucci. Por Ana Elisa Arriaga “–Quiero insistir en algo: ¿quién fue, en los hechos concretos y a lo largo de su vida, su peor enemigo? Agustín Tosco –No podría citar a nadie porque yo tomo a la gente por lo que representa. Le explico: si uno considera un aspecto personal de un individuo, no está en una lucha social, política. Para mí, cada uno es representante de una actitud o posición de su clase. Si yo hubiera sido un hombre individualista hubiera tenido un enemigo personal. Pero yo no tengo enemigos personales; simplemente, hay gente que persigue intereses contrapuestos a los nuestros, que claudica, que traiciona… Y entonces pasan a ser nuestros enemigos”1. Hace un par de años, en pleno conflicto por las retenciones a las exportaciones de granos entre el gobierno de Cristina Fernández y las corporaciones agrícolas ganaderas, un juez federal reabría la causa que investigaba el asesinato de José Ignacio Rucci a partir de la publicación de un libro novelado en el que se afirmaba la responsabilidad de montoneros sobre dicho episodio2. Lo llamativo del suceso no fue el oportunismo editorial que buscaba instalar “la teoría del empate” al tiempo que cuestionaba la política de derechos humanos del gobierno en pleno proceso de realineamiento del campo opositor al Kircnerismo3, sino que el propio secretario general de la CGT, Hugo Moyano, apoyara la reapertura de la causa Rucci. Esto último vino acompañado de una suerte de reivindicación de la figura de Rucci en tanto líder sindical y fue en este marco que desde distintos sectores y con distintas intenciones se recordó su rivalidad pública con Agustín Tosco inmortalizada en aquel famoso debate televisivo en el programa “Las dos campanas” del viejo Canal 11, conducido por un joven Gerardo Sofovich4. -

Del Semanario Al Libro. La Escritura Del Rosendo De Rodolfo Walsh Como Construcción Del Vandorismo En La Argentina Del Peronismo Fracturado*

Trabajo y Sociedad Sociología del trabajo – Estudios culturales – Narrativas sociológicas y literarias NB - Núcleo Básico de Revistas Científicas Argentinas del CONICET Nº 18, vol. XV, Verano 2012, Santiago del Estero, Argentina ISSN 1514-6871 (Caicyt-Conicet) - www.unse.edu.ar/trabajoysociedad Del semanario al libro. La escritura del Rosendo de Rodolfo Walsh como construcción del vandorismo en la Argentina del peronismo fracturado* From the weekly to the book. The writing of Rodolfo Walsh’s Rosendo as the construction of the vandorismo in the Argentina of broken Peronism Darío DAWYD** Recibido: 2.2.11 Recibido con modificaciones: 22.7.11 Aprobado Definitivamente: 23.8.11 RESUMEN En el presente artículo se reconstruye la investigación que Rodolfo Walsh realizó sobre el enfrentamiento que costó la vida de Rosendo García, Domingo Blajaquis y Juan Zalazar y que publicó en siete notas en el semanario CGT entre el 16 de mayo y el 27 de junio de 1968. Aquellas notas son contrastadas con su publicación posterior en formato de libro como ¿Quien mató a Rosendo? en mayo de 1969 y se busca destacar las diferencias entre ambos formatos y contextos. Estas diferencias permiten relevar el contexto político acelerado en que se produjeron y la gran distancia entre un momento y otro a pesar de que transcurrió solo un año entre ambos. Con ello se pretende revisitar una de las investigaciones menos abordadas de Walsh y ponerla en contexto al interior de una etapa político-sindical poco estudiada, especialmente los significados de la división de la CGT y el peronismo, en tanto Walsh había retomado su militancia política y estrechado sus primeros vínculos con una de las fracciones del peronismo en disputa. -

“Open Veins of Latin America” by Eduardo Galeano

OPEN VEINS OF LATIN AMERICA 1 also by EDUARDO GALEANO Days and Nights of Love and War Memory of Fire: Volume I, Genesis Volume II, Faces and Masks Volume III, Century of the Wind The Book of Embraces 2 Eduardo Galeano OPEN VEINS of LATIN AMERICA FIVE CENTURIES OF THE PILLAGE 0F A CONTINENT Translated by Cedric Belfrage 25TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION FOREWARD by Isabel Allende LATIN AMERICA BUREAU London 3 Copyright © 1973,1997 by Monthly Review Press All Rights Reserved Originally published as Las venas abiertas de America Latina by Siglo XXI Editores, Mexico, copyright © 1971 by Siglo XXI Editores Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publishing Data Galeano, Eduardo H., 1940- [Venas abiertas de America Latina, English] Open veins of Latin America : five centuries or the pillage of a continent / Eduardo Galeano ; translated by Cedric Belfrage. — 25th anniversary ed. / foreword by Isabel Allende. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-85345-991-6 (pbk.:alk.paper).— ISBN 0-85345-990-8 (cloth) 1. Latin America— Economic conditions. 1. Title. HC125.G25313 1997 330.98— dc21 97-44750 CIP Monthly Review Press 122 West 27th Street New York, NY 10001 Manufactured in the United States of America 4 “We have maintained a silence closely resembling stupidity”. --From the Revolutionary Proclamation of the Junta Tuitiva, La Paz, July 16, 1809 5 Contents FOREWORD BY ISABEL ALLENDE ..........................................................IX FROM IN DEFENSE OF THE WORD ........................................................XIV ACKNOWLEDGEMENT… … ..........................................................................X INTRODUCTION: 120 MILLION CHILDRENIN THE EYE OF THE HURRICANE .....................................................… ...........1 PART I: MANKIND'S POVERTY AS A CONSEQUENCE OF THE WEALTH OF THE LAND 1. -

Immigrants of a Different Religion: Jewish Argentines

IMMIGRANTS OF A DIFFERENT RELIGION: JEWISH ARGENTINES AND THE BOUNDARIES OF ARGENTINIDAD, 1919-2009 By JOHN DIZGUN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Samuel L. Baily and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2010 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Immigrants of a Different Religion: Jewish Argentines and the Boundaries of Argentinidad, 1919-2009 By JOHN DIZGUN Dissertation Director: Samuel L. Baily This study explores Jewish and non-Jewish Argentine reactions and responses to four pivotal events that unfolded in the twentieth century: the 1919 Semana Trágica, the Catholic education decrees of the 1940s, the 1962 Sirota Affair, and the 1976-1983 Dirty War. The methodological decision to focus on four physically and/or culturally violent acts is intentional: while the passionate and emotive reactions and responses to those events may not reflect everyday political, cultural, and social norms in twentieth-century Argentine society, they provide a compelling opportunity to test the ever-changing meaning, boundaries, and limitations of argentinidad over the past century. The four episodes help to reveal the challenges Argentines have faced in assimilating a religious minority and what those efforts suggest about how various groups have sought to define and control what it has meant to be “Argentine” over time. Scholars such as Samuel Baily, Fernando DeVoto, José Moya and others have done an excellent job highlighting how Italian and Spanish immigrants have negotiated and navigated the ii competing demands of ‘ethnic’ preservation and ‘national’ integration in Argentina. -

Cijada Peronista” (Páginas 176/177)

Poder Judicial de la Nación ///nos Aires, 10 de agosto de 2012. AUTOS Y VISTOS: Para resolver en la presente causa n° 13683/08 caratulada “N.N. s/ asociación ilícita” del registro de esta Secretaría n° 8 de este Juzgado a mi cargo; Y CONSIDERANDO: I. HECHO INVESTIGADO. El objeto de investigación de las presentes actuaciones está constituido por el homicidio de José Ignacio Rucci ocurrido el día 25 de septiembre de 1973, aproximadamente a las 12.10 horas en la avenida Avellaneda frente a la altura catastral n° 2953 de esta ciudad; oportunidad en la que el Secretario de la Confederación General del Trabajo recibió veinticinco disparos de armas de fuego en circunstancias en que fue atacado por un grupo de personas que detonaron explosivos y generaron un tiroteo que duró aproximadamente quince minutos. L A I Previo a efectuar un desarrollo de los características particulares del C I asesinato, resulta relevante destacar que desde su comisión hasta el año 2008, F transcurrieron treinta y cinco años en los que no se lograron reunir elementos O conducentes a su esclarecimiento lo que derivó en que la causa fuera archivada en tres O oportunidades hasta que, finalmente, el 25 de septiembre de ese año este Tribunal S U procedió a su reapertura en virtud de la presentación efectuada por los hijos de Rucci con motivo de la publicación del libro “Operación Traviata” de Ceferino Reato. Sentado ello, considero que la exposición del hecho debe partir de su planificación en la que se demuestra la sofisticación con la que fue llevado a cabo el operativo. -

Argentina Arde: Art As a Tool for Social Struggle

ARGENTINA ARDE: ART AS A TOOL FOR SOCIAL STRUGGLE Veronika Miralles B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2001 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Latin American Studies Program of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology O Veronika Miralles 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Approval Name: Verdnika Miralles Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Argentina Arde: Art as a Tool for Social Struggle Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Alexander Dawson Dr. Mdnica Escudero Senior Supervisor Senior Lecturer Latin American Studies Program Department of Sociology and Anthropology Simon Fraser University Dr. Rita De Grandis Member Associate Professor French, Hispanic and Italian Studies Program The University of British Columbia Dr. Jerald Zaslove External Examiner Emeritus Professor Departments of English and Humanities Simon Fraser University Date Approved: 20 May 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. -

La OIT Y Las Dictaduras Latinoamericanas: Una Aproximación Al Caso 842 Contra Argentina

DOSSIER Anuario del Instituto de Historia Argentina, vol. 17, nº 1, e037, junio 2017. ISSN 2314-257X Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Historia Argentina y Americana La OIT y las dictaduras latinoamericanas: una aproximación al Caso 842 contra Argentina The ILO and the Latin American dictatorships: an introductory approach to the study of the Case 842 against Argentina Luciana Zorzoli * * IdIHCS – Universidad Nacional de La Plata - CONICET, Argentina | [email protected] PALABRAS CLAVE RESUMEN Argentina (1976-1983) Este artículo realizará una aproximación al estudio del Caso 842 abierto en marzo de 1976 en las oficinas de la Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT), en Suiza, contra el gobierno militar Organización Internacional argentino por violaciones a la libertad sindical. Los materiales que lo componen, por su riqueza y del Trabajo (OIT) extrañez, lo convierten en una fuente inestimable para comprender tanto la acción internacional del autodenominado Proceso de Reorganización Nacional (PRN) como las relaciones del mismo con la Caso 842 dirigencia sindical argentina, con las oposiciones internas y externas y con el organismo en cuestión. Gabriel Osvaldo Martínez Centrándonos en las denuncias recibidas en el organismo, las respuestas argentinas y la estrategia desplegada por el PRN y sus aliados civiles y las acciones emprendidas por la OIT se revisará la Antonio Vitaic Jakasa dinámica del Caso y se dejarán planteados elementos para futuras indagaciones. KEYWORDS ABSTRACT Argentina (1976-1983) This article explores the Case 842 opened in March 1976 at the offices of the International Labour Organization (ILO), in Switzerland, against the Argentinean military government for freedom of International Labour association violations. -

CGT De Los Argentinos

RAIMUNDO ONGARO Secretario General de la CGT de los Argentinos El Programa del 1º de Mayo de la CGT de los Argentinos. Un resumen con algunos de los documen- tos y acciones protagonizadas por los trabajadores/as y el pueblo de nuestra Patria en el período Marzo de 1968 a Marzo de 1973. CGT de los ARGENTINOS Por una Patria Justa, Libre y Soberana, LA PATRIA SOCIALISTA Solo el Pueblo Salvará al Pueblo Introducción Consejo Directivo de la CGT de los Argentinos Prólogo de Rodolfo Walsh Palabras iniciales, por Ricardo Carpani Congreso Normalizador de la CGT: la hora de la verdad Carta de Perón Programa del 1º de Mayo Violentos con los Argentinos, complacientes con el extranjero Las calles son del Pueblo El salario de los monopolios Los monopolios en el poder Unirse desde abajo, organizarse combatiendo Salario real: ¿carteristas en el gobierno? La paz de Onganía Carta de Perón Viernes 28: Todos con Todo Azopardo medita, el pueblo lucha Liberación Nacional Coria: el hombre de la cara pintada La explotación de los obreros rurales CGT DE LOS ARGENTINOS 3 “Unirse desde abajo, organizarse combatiendo” Raimundo Ongaro 4 CGT DE LOS ARGENTINOS.. CGT DE LOS ARGENTINOS 5.. RAIMUNDO ONGARO Secretario General de la CGT de los Argentinos El Programa del 1º de Mayo de la CGT de los Argentinos. Un resumen con algunos de los documentos y acciones protagonizadas por los trabajadores/as y el pueblo de nuestra Patria en el período marzo de 1968 a marzo de 1973. C G T DE LOS ARGENTINOS Antes de la victoria del 11 de marzo de 1973, y mientras desde las organizaciones del pueblo poníamos las pala- bras y lo que hace falta respondiendo a la violencia de la dictadura militar y el sistema explotador, dijimos tam- bién lo siguiente: “La historia se repite, aunque nunca del mismo modo. -

![El Nacimiento De La CGT De Los Argentinos Y Algunas Líneas Para Pensar Su Desarrollo Posterior [1968-1969]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8061/el-nacimiento-de-la-cgt-de-los-argentinos-y-algunas-l%C3%ADneas-para-pensar-su-desarrollo-posterior-1968-1969-8598061.webp)

El Nacimiento De La CGT De Los Argentinos Y Algunas Líneas Para Pensar Su Desarrollo Posterior [1968-1969]

Sotelo, Luciana Más vale honra sin sindicatos que sindicatos sin honra: El nacimiento de la CGT de los Argentinos y algunas líneas para pensar su desarrollo posterior [1968-1969] Tesis presentada para la obtención del grado de Licenciada en Sociología Director: Tortti, María Cristina Este documento está disponible para su consulta y descarga en Memoria Académica, el repositorio institucional de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata, que procura la reunión, el registro, la difusión y la preservación de la producción científico-académica édita e inédita de los miembros de su comunidad académica. Para más información, visite el sitio www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta iniciativa está a cargo de BIBHUMA, la Biblioteca de la Facultad, que lleva adelante las tareas de gestión y coordinación para la concre- ción de los objetivos planteados. Para más información, visite el sitio www.bibhuma.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Cita sugerida Sotelo, L. (2007) Más vale honra sin sindicatos que sindicatos sin honra: El nacimiento de la CGT de los Argentinos y algunas líneas para pensar su desarrollo posterior [1968-1969] [en línea]. Tesis de grado. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Disponible en: http://www.memoria. fahce.unlp.edu.ar/tesis/te.485/te.485.pdf Licenciamiento Esta obra está bajo una licencia Atribución-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Argentina de Creative Commons. Para ver una copia breve de esta licencia, visite http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ar/. Para ver la licencia completa en código legal, visite http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ar/legalcode. -

Línea DE Tiempo

historia ubicación Av. Costanera Norte El Parque de la Memoria- Rafael Obligado 6745 POLÍTICA Y SOCIEDAD 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 (adyacente a ciudad universitaria) cp 1428-Ciudad Autónoma LÍNea Monumento a las Víctimas de Buenos Aires parque de la memoria 7 teléfonos: (+54) 11 4787-0999 / 6937 del Terrorismo de Estado, En esta línea de tiempo se desplie- [email protected] DE a través de su Consejo gan algunos hechos y procesos de la monumento a las víctimas historia de la Argentina entre 1969 del terrorismo de estado horarios Del 1 de marzo al 30 de noviembre de Gestión, conformado y 1983. Estas fechas remiten a im- sala pays Abierto todos los días de 10 a 18. portantes acontecimientos: en mayo río de la plata Del 1 de diciembre al 28 de febrero tieMpo Lunes a viernes de 10 a 19. por los organismos de de 1969 tuvo lugar el “cordobazo”, ciclovía Sábados, domingos y feriados de 10 a 20. una de las rebeliones populares más Sala PAyS: MONUMENto derechos humanos, la esculturas Lunes a viernes de 10 a 18. importantes de nuestra historia, y Sábados, domingos y feriados de 11 a 19. A las VictiMas Universidad de Buenos en 1983 finalizó la última dictadura acceso habilitado militar. estela d del teRRORISMO plaza seca cómo llegar Aires y el Gobierno de la tren: DE estado Desde la década de 1950 se habían Belgrano Norte – Estación desarrollado importantes experien- Agustín Tosco al frente de las columnas de trabajadores Pintada callejera de las organizaciones revolucionarias.