An Introduction to Vertigo, in Zero Gravity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XXIX Congress Report XXIX Planetary Congress • Austria • 2016 Photos: OEWF

XXIX Congress Report XXIX Planetary Congress • Austria • 2016 Photos: OEWF 1 John-David Bartoe, 2 Alexander Ivanchenkov, 3 Ulrich Walter, 4 Gerhard Thiele, 5 Georgi Iva- nov, 6 Yuri Gidzenko, 7 Bertalan Farkas, 8 Kevin Ford, 9 Pavel Vinogradov, 10 Charlie Walker, 11 Kimiya Yui, 12 Anatoli Artsebarskii, 13 Shannon Lucid, 14 Reinhold Ewald, 15 Claudie Haigneré, 16 Joe Acaba, 17 Ernst Messerschmid, 18 Jan Davis, 19 Franz Viehbock, 20 Loren Shriver, 21 Miroslaw Hermaszewski. 22 Sultan bin Salman al-Saud, 23 Yang Liwei, 24 Richard Garriott, 25 Mark Brown, 26 Carl Walz, 27 Bill McArthur, 28 Owen Garriott, 29 Anna Fisher, 30 George Zam- ka, 31 Rick Hieb, 32 Jerry Ross, 33 Alexander Volkov, 34 André Kuipers, 35 Jean-Pierre Haign- eré, 36 Toktar Aubakirov, 37 Kay Hire, 38 Michael Fincke, 39 John Fabian, 40 Pedro Duque, 41 Michael Foreman, 42 Sergei Avdeev, 43 Vladimir Kovolyonok, 44 Alexandar Aleksandrov, 45 Alexander Alexandrov, 46 Drew Feustel, 47 Dumitru Prunariu, 48 Alexei Leonov, 49 Rusty Sch- weickart, 50 Klaus-Dietrich Flade, 51 Anton Shkaplerov, 52 Alexander Samokutyaev, 53 Sergei Krikalev, 54 Viktor Savinykh, 55 Soichi Noguchi, 56 Bonnie Dunbar, 57 Vladimir Aksyonov, 58 Scott Altman, 59 Yuri Baturin, 60 Susan Helms, 61 Ulf Merbold, 62 Stephanie Wilson, 63 Chiaki Mukai, 64 Charlie Camarda, 65 Julie Payette, 66 Dick Richards, 67 Yuri Usachev, 68 Michael Lo- pez-Alegria, 69 Jim Voss, 70 Rex Walheim, 71 Oleg Atkov, 72 Bobby Satcher, 73 Valeri Tokarev, 74 Sandy Magnus, 75 Bo Bobko, 76 Helen Sharman, 77 Susan Kilrain, 78 Pam Melroy, 79 Janet Kavandi, 80 Tony Antonelli, 81 Sergei Zalyotin, 82 Frank De Winne, 83 Alexander Balandin, 84 Sheikh Muszaphar, 85 Christer Fuglesang, 86 Nikolai Budarin, 87 Salizhan Sharipov, 88 Vladimir Titov, 89 Bill Readdy, 90 Bruce McCandless II, 91 Vyacheslav Zudov, 92 Brian Duffy, 93 Randy Bresnik, 94 Oleg Artemiev XXIX Planetary Congress • Austria • 2016 One hundred and four astronauts and cosmonauts from 21 nations gathered Oc- tober 3-7, 2016 in Vienna, Austria for the XXIX Planetary Congress of the Associa- tion of Space Explorers. -

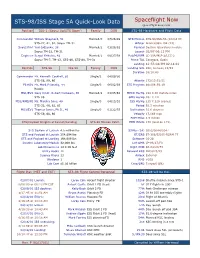

Spaceflight Now STS-98/ISS Stage 5A Quick-Look Data

STS-98/ISS Stage 5A Quick-Look Data Spaceflight Now spaceflightnow.com Position ISS-1 (Soyuz Up/STS Down) Family DOB STS-98 Hardware and Flight Data Commander William Shepherd, 51 Married/0 07/26/49 STS Mission STS-98/ISS-5A (102nd flt) STS-27, 41, 52, Soyuz TM-31 Orbiter Atlantis/OV-104 (23) Soyuz Pilot Yuri Gidzenko, 38 Married/2 03/26/62 Payload Destiny laboratory module Soyuz TM-22, TM-31 Launch 02/07 06:13 PM Engineer Sergei Krikalev, 42 Married/1 08/27/58 Pad/MLP/FR LC-39A/MLP-2/LCC-2 Soyuz TM-7, TM-12, STS-60, STS-88, TM-31 Prime TAL Zaragoza, Spain Landing 12:53:08 PM 02.18.01 Position STS-98 ISS-5A Family DOB Landing Site KSC, Runway 15/33 Duration 10/18:40 Commander Mr. Kenneth Cockrell, 50 Single/2 04/09/50 STS-56, 69, 80 Atlantis 172/13:51:51 Pilot/IV Mr. Mark Polansky, 44 Single/0 06/02/56 STS Program 881/06:59:19 Rookie MS1/EV2 Navy Cmdr. Robert Curbeam, 38 Married/2 03/05/62 MECO Ha/Hp 194 X 46 statute miles STS-85 OMS Ha/Hp 201 X 121 MS2/RMS/FE Ms. Marsha Ivins, 49 Single/0 04/15/51 ISS Ha/Hp 235 X 229 (varies) STS-32, 46, 62, 81 Period 92.3 minutes MS3/EV1 Thomas Jones, Ph.D., 46 Single/0 01/22/55 Inclination 51.6 degrees STS-59, 68, 80 Velocity 17,169 mph EOM Miles 4.5 million STS/Payload Weights at Launch/Landing STS-98 Mission Patch EOM Orbits 170 (land on 171) STS System at Launch 4.5 million lbs SSMEs (2A) 2052/2044/2047 STS and Payload at Launch 254,694 lbs ET/SRB ET-106/BI105-RSRM 77 STS and Payload at Landing 198,909 lbs Software OI-28 Destiny Laboratory Module 32,000 lbs Left OMS LP-03/27/F3 Lab Dimensions 14 -

Agent Based Modeling of Collaboration and Work Practices Onboard the International Space Station

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20020063473 2020-07-22T18:34:32+00:00Z Agent Based Modeling of Collaboration and Work Practices Onboard the International Space Station Alessandro A cquisti School of Information Management and Systems, UC Berkeley 102 South Hall Berkeley, CA 94720 510-823-5008 [email protected] Maarten Sierhuis RIACS, NASA Ames Research Center T35B-1 Moffett Field, CA 94035 650-604-4917 msierhuis @mail. arc. nasa. gov William J. Clancev NASA Ames Research Center & Institute for Human and Machine Cognition, University of West Florida MS 269-3 Moffett Field, CA 94035 650-604-2526 [email protected] Jeffrey M. Bradshaw Institute for Human and Machine Cognition, University of West Florida 40 S. Alcaniz Pensacola, FL 32501 850-202-4422 [email protected] Keywords: Agent-Based Social Simulations, International Space Station, Human-Computer Interaction. ABSTRACT: The International Space Station is one the most complex projects ever, with numerous interdependent constraints affecting productivity and crew safety. This requires planning years before crew expeditions, and the use of sophisticated scheduling tools. Human work practices, however, are difficult to study and represent within traditional planning tools. We present an agent-based model and simulation of the activities and work practices of astronauts onboard the ISS based on an agent-oriented approach. The model represents "a day in the life" of the ISS crew and is developed in Brahms--an agent-oriented, activity-based language used to model knowledge in situated action and learning in human activities. 1. Introduction ship logs highlight recurring discrepancies between planned crew activities and the reality of onboard life. -

Unit 5 Space Exploration

TOPIC 8 People in Space There are many reasons why all types of technology are developed. In Unit 5, you’ve seen that some technology is developed out of curiosity. Galileo built his telescope because he was curious about the stars and planets. You’ve also learned that some technologies are built to help countries fight an enemy in war. The German V-2 rocket is one example of this. You may have learned in social stud- ies class about the cold war between the United States and the for- mer Soviet Union. There was no fighting with guns or bombs. However, these countries deeply mistrusted each other and became very competitive. They tried to outdo and intimidate each other. This competition thrust these countries into a space race, which was a race to be the first to put satellites and humans into space. Figure 5.57 Space shuttle Atlantis Topic 8 looks at how the desire to go into space drove people to blasts off in 1997 on its way to dock produce technologies that could make space travel a reality. with the Soviet space station Mir. Breaking Free of Earth’s Gravity Although space is only a hundred or so kilometres “up there,” it takes a huge amount of energy to go up and stay up there. The problem is gravity. Imagine throwing a ball as high as you can. Now imagine how hard it would be to throw the ball twice as high or to throw a ball twice as heavy. Gravity always pulls the ball back to Earth. -

The International Space Station: Legal Framework and Current Status, 64 J

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 64 | Issue 4 Article 3 1999 The nI ternational Space Station: Legal Framework and Current Status Rochus Moenter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Rochus Moenter, The International Space Station: Legal Framework and Current Status, 64 J. Air L. & Com. 1033 (1999) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol64/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION: LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND CURRENT STATUS ROCHUS MOENTER I. THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION A. BACKGROUND AND CURRENT STATUS HE DEVELOPMENT and construction of an International Space Station (ISS) began with President Reagan's an- nouncement in 1984 that the United States of America intended to build a permanently inhabited civil space station in the earth's orbit, later labeled "Space Station Freedom."' In con- nection with the announcement, President Reagan invited other countries, in particular Canada, Europe and Japan, to partici- pate in the project. This invitation was subsequently accepted by several countries, including the members of the European Space Agency (ESA).2 Some of the countries accepting were Belgium, the Federal Republic of Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, the United Kingdom, Canada through the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) and the Govern- ment of Japan (GOJ). Many years of negotiations followed, mainly between NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) and the re- spective national space agencies, regarding the construction, de- velopment and operation of an ISS. -

Spaceport News John F

Nov. 12, 2010 Vol. 50, No. 23 Spaceport News John F. Kennedy Space Center - America’s gateway to the universe www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/snews/spnews_toc.html NASA marks decade on ISS By Linda Herridge Spaceport News hat a difference a decade makes. On the 10-year Wanniversary of continuous human presence aboard the Interna- tional Space Station, Nov. 2, NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden com- memorated the milestone by calling the six Expedition 25 crew members Discovery, STS-133 currently living and working on the NET Nov. 30 launch orbiting laboratory. ASA has postponed Bolden spoke to Commander the launch of space Doug Wheelock and his fellow shuttle Discovery to astronauts Scott Kelly and Shannon N no earlier than 4:02 a.m. EST Walker, and Russian cosmonauts on Nov. 30. The delay will al- Fyodor Yurchikhin, Alexander Kaleri low engineers and technicians and Oleg Skripochka, during a news time to diagnose and repair conference that was broadcast live a hydrogen gas leak detected on NASA TV. while filling the external fuel “This global milestone is tank Nov. 5. They also will fix tremendously significant, both for a foam crack on the external NASA and our partners,” Bolden NASA fuel tank’s liquid oxygen said. “It recognizes the success of an intertank flange. The crack was amazing feat of engineering and a NASA astronauts Doug Wheelock (background), Expedition 25 commander; and Scott Kelly, flight engi- neer, are pictured near fresh fruit floating freely in the Unity node of the International Space Station. discovered during de-tanking magnificent leap forward in the story operations. -

Genes in Space 2020 Finalists: Contributing Ideas to Advance Space Biology

Article Genes in Space 2020 Finalists: Contributing Ideas to Advance Space Biology Katy Martin1 1 Genes in Space Porgram Lead INTRODUCTION October 30, 2000 was the last day all humans lived alongside one another on the surface of the Earth. The next day, American astronaut William Shepherd and Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev were launched to the International Space Station (ISS) where they would live for 136 days. While humans had visited space before, this mission was different. It kicked off the era of a continuous human presence in space, an era that has continued unbroken to this day. When we celebrate the upcoming anniversary of this milestone, we will be celebrating the ISS as humanity’s home away from home for the past twenty years. A hub for scientific research of all kinds, the ISS stands as a monument to what is possible when a massive and diverse group of people work together on a global scale to tackle science and engineering challenges previously considered to be insurmountable. Thanks to the efforts of this global team, the ISS is available as a one-of-a-kind research platform for scientists interested in the unique opportunities that microgravity offers. But aspiring scientists need not earn their PhDs before they can get involved in research on the ISS. In 2015, the Genes in Space program was established to grant students access to this extraordinary resource. Genes in Space is a competition for middle and high school students who are interested in becoming space biology pioneers. Contestants submit proposals for DNA science experiments that would expand our understanding of how the conditions of space – e.g., microgravity and cosmic radiation – affect biology. -

The Newsletter of the Directorate of Manned Spaceflight and Microgravity

number 7, december 2001 on station The Newsletter of the Directorate of Manned Spaceflight and Microgravity http://www.esa.int/export/esaHS/ 2001: A Good Year - But Hard Work Lies Ahead Jörg Feustel-Büechl ESA Director of Manned Spaceflight and Microgravity We have had a really excellent 2001 in technical terms. Since the first launch, of Zarya in November 1998, we have had 24 launches either to build up the International Space Station with new equipment and facilities, or to service it – a remarkable achievement. Indeed, there have been 12 launches in 2001 alone! Altogether, we have seen some remarkable hardware progress in the programme and – even better – there have been no major in-orbit problems. So we have created an operational Station with a permanent 3-man crew and we have already seen the first experiments (including European experiments) completed. All in all, the Station is working really well, both in terms of its technical realisation and of the international cooperation between the five Partners. Unfortunately, the rest of the picture is not so rosy.We heard from NASA earlier in 2001 of the likelihood of major cost overruns on their part. So far, overall US costs have been around $25 billion and NASA has announced increases of some $4.8 billion to take Station assembly to completion.The Bush Administration declared this to be unacceptable and initiated a review by the NASA Advisory Council.This Review, chaired by Thomas Young, was tasked to investigate what kind of management, cost and technical changes must be implemented in order to contain the costs within the original funding plan.The outcome includes a number of drastic recommendations not only in management and cost control, but also in the Station’s configuration. -

Icons on the International Space Station

religions Article Eternity in Low Earth Orbit: Icons on the International Space Station Wendy Salmond 1, Justin Walsh 1 and Alice Gorman 2,* 1 Department of Art, Chapman University, Orange, CA 92866, USA; [email protected] (W.S.); [email protected] (J.W.) 2 Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA 5042, Australia * Correspondence: alice.gorman@flinders.edu.au Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 10 November 2020; Published: 17 November 2020 Abstract: This paper investigates the material culture of icons on the International Space Station as part of a complex web of interactions between cosmonauts and the Russian Orthodox Church, reflecting contemporary terrestrial political and social affairs. An analysis of photographs from the International Space Station (ISS) demonstrated that a particular area of the Zvezda module is used for the display of icons, both Orthodox and secular, including the Mother of God of Kazan and Yuri Gagarin. The Orthodox icons are frequently sent to space and returned to Earth at the request of church clerics. In this process, the icons become part of an economy of belief that spans Earth and space. This practice stands in contrast to the prohibition against displaying political/religious imagery in the U.S.-controlled modules of ISS. The icons mark certain areas of ISS as bounded sacred spaces or hierotopies, separated from the limitless outer space beyond the space station walls. Keywords: International Space Station; iconography; hierotopy; material culture; sacred space; cosmonaut 1. Introduction How the perspective of being outside the world—that is, in space—changes personal approaches to spirituality among space travelers has been the subject of numerous studies (e.g., Suedfeld 2006; Weibel 2016, 2020; Weibel and Swanson 2006). -

Spaceflight Now STS-102/ISS-5A.1 Quick-Look Data

STS-102/ISS-5A.1 Quick-Look Data Spaceflight Now spaceflightnow.com Position STS-102 ISS-5A.1 Family DOB STS-102 Hardware and Flight Data Commander Navy. Capt. James Wetherbee, 48 Married/2 11/27/52 STS Mission STS-102/ISS-5A.1 STS-32, 52, 63, 86 Orbiter Discovery/OV-103 (29) Pilot/IV Air Force Lt. Col. James Kelly, 36 Married/4 05/14/64 Payload Crew ferry; MPLM Rookie Launch 06:42:09 AM 03.08.01 MS1/EV3 Andrew Thomas, Ph.D., 49 Single/0 12/18/51 Pad/MLP/FR 39B/MLP-3/FR 2-1 STS-77, 89/Mir7/91 Prime TAL Zaragoza, Spain MS2/FE/EV4 Paul Richards, 36 Married/3 05/20/64 Landing 02:02:00 AM 03.20.01 Rookie Landing Site KSC, Runway 15/33 STS UP ISS Expedition 2 (shuttle up/shuttle down) Duration 11/19:20 ISS-2 CDR Yury Usachev, 43 Married/1 10/09/57 Soyuz TM-18, TM-23, STS-101 Discovery 217/06:17:38 ISS-2/EV1 Mr. James Voss, 52 Married/1 03/03/49 STS Program 894/04:19:22 STS-44, 53, 69, 101 ISS-2/EV2 Air Force Col. Susan Helms, 43 Single/0 02/26/58 MECO Ha/Hp 137 X 36 sm STS-54, 64, 78, 101 OMS Ha/Hp 143 X 121 sm STS DOWN ISS Expedition 1 (Soyuz up/shuttle down) ISS Ha/Hp 235 X 229 (varies) ISS-1 CDR William Shepherd, 51 Married/0 07/26/49 Period 92.3 minutes STS-27, 41, 52, TM-31/ISS-1 Inclination 51.6 degrees ISS-1 Yuri Gidzenko, 38 Married/2 03/26/62 Velocity 17,169 mph Soyuz TM-22, TM-31/ISS-1 EOM Miles 4.86 million ISS-1 Sergei Krikalev, 42 Married/1 08/27/58 EOM Orbits 184 (land on 185) Soyuz TM-7, TM-12, STS-60, STS-88, TM-31/ISS-1 SSMEs (2A) 2056, 2053, 2045 STS-102 Cargo/Element Weights STS-102 Patch ET/SRB 107/BI106-RSRM 78 Software -

Partnership – the Way of the Future for the International Space Station by TARA S

Partnership – The Way of the Future for The International Space Station BY TARA S. MILLER, CPPM, SHUTTLE CHAPTER PHOTO CREDIT: NASA PHOTO CREDIT: Backdropped by the blackness of space and a blue and white Earth, the International Space Station (ISS) is now separated from the Space Shuttle Endeavour following the undocking of the two spacecraft over western Kazakhstan on June 15, 2002. he International Space Station (ISS) is being built by The Reagan Administration, in 1984, first introduced sixteen nations, which includes the United States, the space station program. Since then, the station has been TCanada, Russia, Japan, Brazil, and 11 European redesigned several times to control cost overruns and over- nations (Halvorson). Through the use of Memorandum’s of come technical flaws. The original international partners Understanding (MOUs) / bartering agreements, these coun- involved in this program were the European Space Agency tries have agreed to cooperate and work together to build a (ESA), the National Space Development Agency of Japan permanent science institute in space. The agreements estab- (NASDA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) (Aug. lished the framework for cooperation among the Interna- 1998). tional Partners (IPs) on the design, development, operation, MOUs between the National Aeronautics and Space and utilization of the Space Station. The ISS is a very large, Administration (NASA) of the United States of America complex international cooperative science and engineering and the Russian Space Agency, the Canadian Space program. Each participating country is contributing its Agency, the European Space Agency, and the Japanese expertise to the space station. Astronauts from around the Government are the mechanism for establishing the Inter- world will work together to connect the different sections of national Space Station. -

EUROMIR 20Th Anniversary

EUROMIR95 20th Anniversary The significance of the EUROMIR95 Mission for Columbus Operations and for the Columbus Control Center (Col-CC) at DLR-GSOC Oberpfaffenhofen The 179-day flight (launched 3rd September 1995) of ESA astronaut Thomas Reiter onboard the Russian Space Station Mir came to a successful end on 29 February 1996 with the safe landing of the Soyuz TM-22 capsule near Arkalyk in Kazakhstan. The Euromir 95 crew consisted of the Russian cosmonauts Commander Yuri Gidzenko and Engineer Sergei Avdeev, and ESA Astronaut Thomas Reiter. This mission, referred to as EUROMIR 95, was part of ESA's precursor flight program and followed the EUROMIR94 mission (3 Oct - 4 Nov, 1994).The overall preparations to implement these two missions were started in spring of 1993, when first negotiations with the responsible Russian space company, RSC Energia of Moscow, were initiated. One of the major objectives reflected in the Resolutions adopted at the ESA Council meeting at ministerial level in Granada on 10 November 1992 was to widen and strengthen international cooperation, hereby taking into account the evolution of the geopolitical context. Particular emphasis was given to an intensification of the cooperation with the Russian Federation (ESNCM/ CIV/Res.3 (Final)). Consequently, ESA and the Russian Space Agency signed an agreement to cooperate on manned space infrastructure and space transportation systems in the 1993-95 timeframe. Two major space station elements (European Robotics Arm-ERA and a new MIR Data Management System -DMS-R) were developed in the framework of this intensified cooperation. EUROMIR 94 and EUROMIR 95, the two missions of ESA astronauts on board the Russian space station Mir, were also a result of this cooperation.