Social Negotiation & Drinking Spaces in Frontier Resource Extraction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malcolm Lowry: a Study of the Sea Metaphor in "Ultramarine" and "Under the Volcano"

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 Malcolm Lowry: A study of the sea metaphor in "Ultramarine" and "Under the Volcano". Bernadette Wild University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Wild, Bernadette, "Malcolm Lowry: A study of the sea metaphor in "Ultramarine" and "Under the Volcano"." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6505. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6505 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. MALCOLM LOWRY: A STUDY OF THE SEA METAPHOR IN ULTRAMARINE AND UNDER THE VOLCANO BY SISTER BERNADETTE WILD A T hesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of English in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

Download a Printable Version of Maine Heritage

COAST-WIDE EDITION COAST-WIDE FALL ‘20 FALL Maine Heritage MCHT Preserves See More Use Than Ever Before © Courtney Reichert Cousins from Brunswick and Freeport play on Whaleboat Island Preserve before enjoying their first overnight camping experience on an island. For Maine Coast Heritage “I’ve never seen so many people than ever before, including (to Trust land stewards, a nine-to- out on Casco Bay and using name just a couple) uncontrolled five workday isn’t a common our island preserves,” says dogs and left-behind waste. She occurrence during field season. Caitlin Gerber. “Just about seized the opportunity to educate Weather, tides, boat sharing, every available campsite was preserve users in an op-ed in the volunteer availability—there’s in use on any given night and local paper. Earlier in the year, lots of coordination involved, particularly on the weekends.” when COVID-19 hit, MCHT’s and flexibility is essential. That Caitlin would make the rounds on Land Trust Program Director said, it’s also not common for those Saturday nights, checking Warren Whitney gathered a group a land steward to fire up a boat in on campers, ensuring fires were from the conservation community below the high tide mark, and on a Saturday evening to go and state resource agencies to explaining to some that camping check on island preserves, create clear guidelines for safe is limited to designated sites. which is exactly what MCHT’s and responsible use of conserved Southern Maine Regional Land Thankfully, the vast majority lands, which were shared across Steward found herself doing of visitors were respectful. -

2019-2020 Year in Review

Table of Contents 3 Director’s Welcome 7 Objects in Space: A Conversation with Barry Bergdoll and Charlotte Vignon 17 Glorious Excess: Dr. Susan Weber on Victorian Majolica 23 Object Lessons: Inside the Lab for Teen Thinkers 33 Teaching 43 Faculty Year in Review 50 Internships, Admissions, and Student Travel and Research 55 Research and Exhibitions 69 Gallery 82 Publications 83 Digital Media Lab 85 Library 87 Public Programs 97 Fundraising and Special Events Eileen Gray. Transat chair owned by the Maharaja of Indore, from the Manik Bagh Palace, 1930. Lacquered wood, nickel-plated brass, leather, canvas. Private collection. Copyright 2014 Phillips Auctioneers LLC. All Rights Reserved. Director’s Welcome For me, Bard Graduate Center’s Quarter-Century Celebration this year was, at its heart, a tribute to our alumni. From our first, astonishing incoming class to our most recent one (which, in a first for BGC, I met over Zoom), our students are what I am most proud of. That first class put their trust in a fledgling institution that burst upon the academic art world to rectify an as-yet-undiagnosed need for a place to train the next generation of professional students of objects. Those beginning their journey this fall now put their trust in an established leader who they expect will prepare them to join a vital field of study, whether in the university, museum, or market. What a difference a generation makes! I am also intensely proud of how seriously BGC takes its obligation to develop next-generation scholarship in decorative arts, design his- tory, and material culture. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) MAINE STATE CULTURAL AFFAIRS COUNCIL 2012 Annual Report Maine Arts Commission Maine Historic Preservation Commission Maine Historical Society Maine Humanities Council Maine State Library Maine State Museum Submitted to the Joint Committee on Education and Cultural Affairs June 2013 Maine State Cultural Affairs Council Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 Maine State Cultural Affairs Council History and Purpose ............................................................... 3 MAINE STATE CULTURAL AFFAIRS COUNCIL .................................................................... 5 Purpose and Organization: .................................................................................................................... 5 Program / Acquisitions: ........................................................................................................................... 5 Accomplishments:.......................................................................................................................................5 Program Needs: ........................................................................................................................................6 -

Pêcheurs, Pâturages, Et Petit Jardins: a Nineteenth-Century Gardien Homestead in the Petit Nord, Newfoundland

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI* Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57435-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57435-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne sur la Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de la vie privee, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont ete enleves de thesis. -

Material Culture from the Wilson Farm Tenancy: Artifact Analysis

AT THE ROAD’S EDGE: FINAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE WILSON FARM TENANCY SITE 7 Material Culture from the Wilson Farm Tenancy: Artifact Analysis LABORATORY AND ANALYTICAL METHODS The URS laboratory in Burlington, New Jersey, processed the artifacts recovered from Site 7NC- F-94. All artifacts were initially cleaned, labeled, and bagged (throughout, technicians maintained the excavation provenience integrity of each artifact). Stable artifacts were washed in water with Orvis soap using a soft bristle brush, then air-dried; in some cases, on an individual basis, artifacts deemed too delicate to wash were dry brushed—this is often the case with badly deteriorated iron and bone objects considered noteworthy. Technicians then labeled items such as prehistoric lithics, historic ceramics, bone, glass, and some metal artifacts. Labeling was conducted using an acid free, conservation grade, .25mm Staedtler marking pen applied over a base coat of Acyloid B72 resin; once the ink dried, the label was sealed with a second layer of Acyloid B72. The information marked on the artifacts consisted of the provenience catalog number. Once the artifacts were processed, they were then inventoried in a Microsoft Access database. The artifacts were sorted according to functional groups and material composition in this inventory. Separate analyses were conducted on the artifacts and inventory data to answer site spatial and temporal questions. Outside consultants analyzed the floral and faunal materials. URS conducted soil flotation. In order to examine the spatial distributions of artifacts in the plowzone, we entered the data for certain artifact types into the Surfer 8.06.39 contouring and surface-mapping program. -

Ceramics Monthly Jun90 Cei069

William C. Hunt........................................Editor Ruth C. Buder.......................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager........................... Art Director Kim Schomburg....................Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley................... Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver.................Circulation Assistant Jayne Lx>hr.......................Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher.................Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.................................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $20, two years $36, three years $50. Add $8 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine address label and your new ad dress to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Of fices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustra tions, announcements and news releases about ceramics are welcome and will be considered for publication. A booklet de scribing standards and procedures for the preparation and submission of a manu script is available upon request. Mail sub missions to: The Editor, Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Infor mation may also be sent by fax: (614) 488- 4561; or submitted on 3.5-inch microdisk- ettes readable with an Apple Macintosh™ computer system. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Addition ally, articles in each issue ofCeramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index; on-line (com puter) indexing is available through Wilson- line, 950 University Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452. -

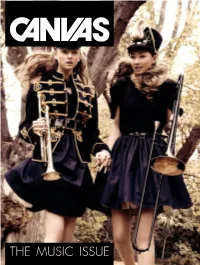

Canvas 06 Music.Pdf

THE MUSIC ISSUE ALTER I think I have a pretty cool job as and design, but we’ve bridged the editor of an online magazine but gap between the two by including PAGE 3 if I could choose my dream job some of our favourite bands and I’d be in a band. Can’t sing, can’t artists who are both musical and play any musical instrument, bar fashionable and creative. some basic work with a recorder, but it’s still a (pipe) dream of mine We have been very lucky to again DID I STEP ON YOUR TRUMPET? to be a front woman of some sort work with Nick Blair and Jason of pop/rock/indie group. Music is Henley for our editorials, and PAGE 7 important to me. Some of my best welcome contributing writer memories have been guided by a Seema Duggal to the Canvas song, a band, a concert. I team. I met my husband at Livid SHAKE THAT DEVIL Festival while watching Har Mar CATHERINE MCPHEE Superstar. We were recently EDITOR PAGE 13 married and are spending our honeymoon at the Meredith Music Festival. So it’s no surprise that sooner or later we put together a MUSIC issue for Canvas. THE HORRORS This issue’s theme is kind of a departure for us, considering we PAGE 21 tend to concentrate on fashion MISS FITZ PAGE 23 UNCOVERED PAGE 28 CREATIVE DIRECTOR/FOUNDER CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Catherine McPhee NICK BLAIR JASON HENLEY DESIGNER James Johnston COVER COPYRIGHT & DISCLAIMER EDITORIAL MANAGER PHOTOGRAPHY Nick Blair Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission by Canvas is strictly prohibited. -

Proquest Dissertations

FRONTIERS, OCEANS AND COASTAL CULTURES: A PRELIMINARY RECONNAISSANCE by David R. Jones A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary's University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Atlantic Canada Studues December, 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright David R. Jones Approved: Dr. M. Brook Taylor External Examiner Dr. Peter Twohig Reader Dr. John G. Reid Supervisor September 10, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46160-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46160-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Antiques-February-1990-Victorian-Majolica.Pdf

if It1ud!!&/ ';"(* ./J1!11L. /,0t£~ltldtiJlR~~~rf;t;t r{/'~dff;z, f!71/#/~i' 4 . !(Jf~f{ltiJ(/dwc.e. dJ /¥ C\-Cit!Ja? /Hc a4 ~- t1 . I. le/. {./ ,...."".. //,; J.(f)':J{"&Tf ,4.~'.£1//,/1;"~._L~ • ~. ~~f tn.~! .....•. ... PL IL Baseball and Soccer pitcher made by Griffen, Smith and Company, PllOeni;'Cville,Pennsylvania. c.1884. Impressed "GSH "in nlOnogram on the bottom. Height 8 inches. The Wedgwood pattern book illustration of the same design is shown in PL Ila. Karmason/Stacke collection; White photograph. PL /la. Design from one of the pattern books of Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent, England. Wedgwood Museum, Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent, England. and Company, Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, and majolica.! New designs for majolica ceased to be made George Jones and Sons. From these books one be• in the early 1890's, and production of majolica ceased comes familiar with the style of the maker and comes early in this century. to appreciate the deliberate choice of details that gives The Minton shape books are valuable not only be• each piece its unity. cause they help date the first production of a piece but By 1836 Herbert Minton (1792- 1858) had succeed• also because they show the development of the eclectic ed his father, Thomas (1765-1836), the founder of the and revivalist styles used by Minton artists. The earli• prestigious Minton firm. In 1848 Joseph Leon Fran• est style used by the firm was inspired by Renaissance ~ois Arnoux (1816-1902) became Minton's art direc• majolica wares.Z Large cache pots, urns, and platters tor, chief chemist, and Herbert Minton's close col• were decorated with flower festoons, oak leaves, car• league. -

Culture Collide (LA) Corona Capital

o1*A *Añ ño1 1 *A ño ñ A o * 1 1 * A o ñ ñ o A 1 * * 1 A o ñ ñ o A 1 * * 1 A o ñ ñ o A 1 * * 1 A #o ñ ñ o A 1 1* Coberturas Especiales Culture Collide (L.A.) Corona Capital (D.F.) Editorial ™ Bienvenidos… La música forma parte fundamental del ser humano gracias al papel que ha jugado y juega en todas las culturas del mundo. Es una constante en la historia de la humanidad. Los instrumentos y sonidos podrán cambiar, pero en esencia siempre será expresión de emociones y sentimientos. México es el punto de enlace entre la música latinoamericana y la estadounidense; somos un país con un gran interés y pasión por la música de todas partes del continente y del orbe. Esa pasión se refleja en las bandas que crean canciones, remixes, covers, en los medios y sobre todo en la audiencia: que asiste a conciertos, busca lo más nuevo, pero que también celebra encontrarse en todo momento con las grandes bandas del pasado. Hoy, y tras una década de existencia, Filter Magazine, la publicación originaria de Estados Unidos, llega a México para compartir lo más actual y relevante, pero también para impulsar a las bandas referentes cuyo legado siempre está allí… esperando ser descubierto. Así que, es un honor presentarles el trabajo que después de varios meses de planeación se consagra en este primer número de Filter México, que cabe resaltar, será la primera publicación musical gratuita de nuestro país, porque sabemos que el modelo editorial tradicional no es viable para un melómano nómada.