Aspen Health Journalism Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit?

The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner Ph.D., Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Leah Robbins May 2020 Copyright by Leah Robbins 2020 Acknowledgements This thesis was made possible by the generous and thoughtful guidance of my two advisors, Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner. Their content expertise, ongoing encouragement, and loving pushback were invaluable to the work. This research topic is complex for the Jewish community and often wrought with pain. My advisors never once questioned my intentions, my integrity as a researcher, or my clear and undeniable commitment to the Jewish people of the past, present, and future. I do not take for granted this gift of trust, which bolstered the work I’m so proud to share. I am also grateful to the entire Hornstein community for making room for me to show up in my fullness, and for saying “yes” to authentically wrestle with my ideas along the way. It’s been a great privilege to stretch and grow alongside you, and I look forward to continuing to shape one another in the years to come. iii ABSTRACT The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Leah Robbins Fascination with the famed “Black-Jewish coalition” in the United States, whether real or imaginary, is hardly a new phenomenon of academic interest. -

California Directory of Radio Tehachapi Templeton Thousand Oaks

California Directory of Radio Taft Format: Classic Hits. Nancy Leichter, gen mgr & gen sls mgr; Marty Torrance Scala, opns dir; Drew Ross, progmg dir; Rick Martel, news dir; Tom Hughes, chief of engrg. KBDS(FM)- June 1986: 103.9 mhz; 8 kw. 328 ft. TL: N35 07 04 KFOX(AM)- January 1998: 1650 khz; 10 kw -D, 490 w -N. TL: N33 53 W119 27 33. Stereo. 6313 Schirra Ct., Bakersfield 93313. Phone: 30 W118 11 03 (D), N33 53 30 W118 11 03 (N). 4525 Wilshire Blvd., (661) 837 -0745. Fax: (661)837-1612. E-mail: network @campesina.com. Thousand Oaks 3rd Fl., Los Angeles 90010. Phone: (323) 935-0606. Fax: (323) Web Site: www.campesina.com. Licensee: Radio Campesina Bakersfield 935 -8885. Web Site: www.koreatimes.com. Licensee: Chagal Inc. (acq 1994; $135,000 plus assumption of debt valued at $283,000. Communications Inc. (acq 5- 25 -00; $30 million). Format: Adult 'KCLU(FM)- Oct 20, 1994: 88.3 mhz; 3.2 kw. Ant 518 ft. TL: N34 13 with AM). Borsari & Paxson. Format: Mexican. Target aud: contemp, Korean. Grant Chang, gen mgr; Yowag Soo Choi, sls dir; co-located 05 W118 56 42. Stereo. 60 W. Olsen Rd., Suite 4400 91360. Phone: Hispanic. mgr; Paul Yo Woong Jim, progmg dir; Joy Kim, chie) of engrg. 25 -54; Jeff Russinsky, pres & nail sls Chavez, (805) 493-3900. Phone: (805) 493 -9200. Fax: (805) 493.3982. Web pres; Anthony Chavez. gen mgr: Dave Whitehead, chief of engrg. Site: www.kclu.org. Licensee: California Lutheran University. Network: NPR, PRI. Leventhal, Senter & Lerman. -

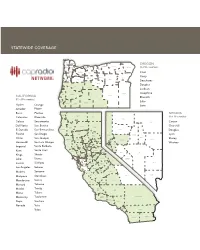

Statewide Coverage

STATEWIDE COVERAGE CLATSOP COLUMBIA OREGON MORROW UMATILLA TILLAMOOK HOOD WALLOWA WASHINGTON MULTNOMAH RIVER (9 of 36 counties) GILLIAM SHERMAN UNION YAMHILL CLACKAMAS WASCO Coos POLK MARION WHEELER Curry JEFFERSON BAKER LINCOLN LINN BENTON GRANT Deschutes CROOK Douglas LANE DESCHUTES Jackson MALHEUR Josephine COOS DOUGLAS HARNEY CALIFORNIA LAKE Klamath (51 of 58 counties) CURRY Lake KLAMATH JOSEPHINE JACKSON Alpine Orange Lane Amador Placer Butte Plumas NEVADA DEL NORTE SISKIYOU Calaveras Riverside MODOC (6 of 16 counties) HUMBOLDT Colusa Sacramento ELKO Carson Del Norte San Benito SHASTA LASSEN Churchill TRINITY El Dorado San Bernardino HUMBOLDT PERSHING Douglas TEHAMA Fresno San Diego WASHOE LANDER Lyon PLUMAS EUREKA Glenn San Joaquin MENDOCINO WHITE PINE Storey GLENN BUTTE SIERRA CHURCHILL STOREY Humboldt San Luis Obispo Washoe NEVADA ORMSBY LYON COLUSA SUTTER YUBA PLACER Imperial Santa Barbara LAKE DOUGLAS Santa Cruz YOLO EL DORADO Kern SONOMA NAPA ALPINE MINERAL NYE SACRAMENTO Kings Shasta AMADOR SOLANO CALAVERAS MARIN TUOLUMNE SAN ESMERALDA Lake Sierra CONTRA JOAQUIN COSTA MONO LINCOLN Lassen Siskiyou ALAMEDA STANISLAUS MARIPOSA SAN MATEO SANTA CLARA Los Angeles Solano MERCED SANTA CRUZ MADERA Madera Sonoma FRESNO SAN CLARK Mariposa Stanislaus BENITO INYO Mendocino Sutter TULARE MONTEREY KINGS Merced Tehama Trinity SAN Modoc LUIS KERN OBISPO Mono Tulare SANTA SAN BERNARDINO Monterey Tuolumne BARBARA VENTURA Napa Ventura LOS ANGELES Nevada Yolo ORANGE Yuba RIVERSIDE IMPERIAL SAN DIEGO CAPRADIO NETWORK: AFFILIATE STATIONS JEFFERSON PUBLIC STATION CITY FREQUENCY STATION CITY FREQUENCY FREQUENCY RADIO - TRANSLATORS KXJZ-FM Sacramento 90.9 KPBS-FM San Diego 89.5 Big Bend, CA 91.3 KXPR-FM Sacramento 88.9 KQVO Calexico 97.7 Brookings, OR 101.7 KXSR-FM Groveland 91.7 KPCC-FM Pasadena 89.3 Burney, CA 90.9 Stockton KUOP-FM 91.3 KUOR-FM Inland Empire 89.1 Callahan/Ft. -

Compton College President Keith Curry

Linda Brown, the central figure of Weather Channel Has New Boss in the Brown v. Board of Education case, Byron Allen, purchases network for dies at age 76 (See page A-12) $300 million (See page C-3) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBERSEPTEMBER 12 17,- 18, 2015 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO 12 $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over EightyYears TheYears Voice The ofVoice Our of Community Our Community Speaking Speaking for Itselffor Itself” THURSDAY, MARCH 29, 2018 AP PHOTO {See FULL STORY A-8} Naomi Wadler, 11, a student at George U.S. Senator Kamala Harris Joins Los Angeles Youth From Left, D’Angelo McDade, a senior at North Lawndale College Mason Elementary School, in Alexandria, Va., Protestors in the #MarchForOurLives/ #NeverAgain Protest Prep High School in Chicago, who was shot while sitting on his porch (AP PHOTO/ANDREW HARNIK) (OFFICE OF U.S. SENATOR KAMALA D. HARRIS) in 2017, and Alex King, a senior at North Lawndale College Prep High School in Chicago,IL AP Photo/Andrew Harnik BY GENOA BARROW Sacramento Observer/ NNPA Member Angry and frustrated residents are demanding answers after a police- involved shooting left an unarmed, Black man dead last week. Stephon Clark, 22, was fatally shot in his Meadowview area backyard Sunday, March 18, after two Sacramento Police Department (SPD) Stephon Clark, 22, was fatally shot by Sacramento officers shot at him more police officers last week. This photo of him with his two than 20 times. Local law young sons has been widely circulated on social media enforcement officers were by family and friends decrying the shooting and calling in the area after receiving for justice. -

Black Silent Majority

Black Silent Majority MICHAEL JAVEN FORTNER Black Silent Majority The Rocke fel ler Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment Cambridge, Mas sa chu setts, and London, England 2015 Copyright © 2015 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Ame rica First printing Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Fortner, Michael Javen, 1979– Black silent majority : the Rocke fel ler drug laws and the politics of punishment / Michael Javen Fortner. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-74399-1 (alk. paper) 1. Discrimination in criminal justice administration— New York (State) 2. African American criminals— New York (State) 3. Drug control— New York (State) 4. African Americans— New York (State)—Social conditions. 5. Middle class—New York (State) I. Title. HV9955.N7F67 2015 364.1'3365089960730747— dc23 2015012136 For Curley Contents Preface ix Introduction “The Reign of Criminal Terror Must Be Stopped Now” 1 1 Rights and Wreckage in Postwar Harlem 24 2 Black Junkies, White Do- Gooders, and the Metcalf- Volker Act of 1962 67 3 Reverend Dempsey’s Crusade and the Rise of Involuntary Commitment in 1966 98 4 Crime, Class, and Confl ict in the Ghetto 133 5 King Heroin and the Development of the Drug Laws in 1973 173 6 Race, Place, and the Tumultuous 1960s and 1970s 217 Conclusion “Liberal Sentiments to Conservative Acts” 257 Notes 283 Ac know ledg ments 335 Index 339 Preface I HAVE NEVER BEEN INCARCERATED. But my brother has— for a long time. I have never been stopped and frisked. -

Contributions by Employer

2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT HOME / CAMPAIGN FINANCE REPORTS AND DATA / PRESIDENTIAL REPORTS / 2008 APRIL MONTHLY / REPORT FOR C00431569 / CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT PO Box 101436 Arlington, Virginia 22210 FEC Committee ID #: C00431569 This report contains activity for a Primary Election Report type: April Monthly This Report is an Amendment Filed 05/22/2008 EMPLOYER SUM NO EMPLOYER WAS SUPPLIED 6,724,037.59 (N,P) ENERGY, INC. 800.00 (SELF) 500.00 (SELF) DOUGLASS & ASSOCI 200.00 - 175.00 1)SAN FRANCISCO PARATRAN 10.50 1-800-FLOWERS.COM 10.00 101 CASINO 187.65 115 R&P BEER 50.00 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FU 120.00 1199 SEIU 210.00 1199SEIU BENEFIT FUNDS 45.00 11I NETWORKS INC 500.00 11TH HOUR PRODUCTIONS, L 250.00 1291/2 JAZZ GRILLE 400.00 15 WEST REALTY ASSOCIATES 250.00 1730 CORP. 140.00 1800FLOWERS.COM 100.00 1ST FRANKLIN FINANCIAL 210.00 20 CENTURY FOX TELEVISIO 150.00 20TH CENTURY FOX 250.00 20TH CENTURY FOX FILM CO 50.00 20TH TELEVISION (FOX) 349.15 21ST CENTURY 100.00 24 SEVEN INC 500.00 24SEVEN INC 100.00 3 KIDS TICKETS INC 121.00 3 VILLAGE CENTRAL SCHOOL 250.00 3000BC 205.00 312 WEST 58TH CORP 2,000.00 321 MANAGEMENT 150.00 321 THEATRICAL MGT 100.00 http://docquery.fec.gov/pres/2008/M4/C00431569/A_EMPLOYER_C00431569.html 1/336 2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT 333 WEST END TENANTS COR 100.00 360 PICTURES 150.00 3B MANUFACTURING 70.00 3D INVESTMENTS 50.00 3D LEADERSHIP, LLC 50.00 3H TECHNOLOGY 100.00 3M 629.18 3M COMPANY 550.00 4-C (SOCIAL SERVICE AGEN 100.00 402EIGHT AVE CORP 2,500.00 47 PICTURES, INC. -

CURRICULUM VITAE ALAN HEDGE, Phd, CPE, C.Erghf, FIEHF, FHFES, FIEA CCSF Faculty Fellow

January 2019 Professor Alan Hedge CURRICULUM VITAE ALAN HEDGE, PhD, CPE, C.ErgHF, FIEHF, FHFES, FIEA CCSF Faculty Fellow Nationality American & British Telephone: 607-255-1957 (office) Mobile: 607-227-1728 (preferred) Fax: 607-255-0305 (office) E- mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ergo.human.cornell.edu ACADEMIC POSITION: Professor Department of Design and Environmental Analysis 2415 Martha Van Rensselaer Hall NYS College of Human Ecology Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14853-4401 UNIVERSITY EDUCATION Bachelor of Science (First class) Special Honors in Zoology. (Subsidiary subjects Physiology and Biochemistry). University of Sheffield, 1970. Master of Science (MS), Zoology University of Sheffield, 1971. Master of Science (MS), Applied Psychology (Ergonomics). Aston University, 1972. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), 1972-74. Submitted and awarded for thesis in Experimental Developmental Cognitive Psychology University of Sheffield, 1979. CURRENT PROFESSIONAL BODIES Certified Professional Ergonomist (CPE), Board of Certification of Professional Ergonomists (2003 – onwards: #1347) Chartered Ergonomist (C.Erg.HF) (2013 - onwards) Fellow, International Ergonomics Association (IEA) Fellow, The Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (U.S.A.) (FHFES) Fellow, The Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors (U.K.) (FIEHF) PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Program chair, National Ergonomics Conference and Exposition 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 IEA Representative for Environmental Design (2011-) Atkinson Center for Sustainable Futures Faculty Fellow -

Complete Bibliography. Updated November 15, 2009 1 Abbott

Complete Bibliography. Updated November 15, 2009 Abbott, Denise. By design: Los angeles is rich in residential architectural styles, and interest in such properties is at an all-time high. Hollywood Reporter no. October (October 18-20, 2002). : S-1-S-2, S-3, S-16. Abercrombie, Brooke and Irmina Kobylko. 2009. Where williams walked: Pasadena architect james V. coane leaves an invisible footprint on his renovation of a 1928 spanish colonial estate designed by los angeles' renowned architect to the stars. Pasadena Weekly, April 1. http://pasadenaweekly.com/cms/story/detail/wh... (accessed 4/28/09). Abrams, Charles. The housing problem and the negro. Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 95, no. 1 (Winter, 1966). : 64-76. Adams, Michael. The incomparable success of paul R. williams. In African american architects in current practice, ed. Jack Travis. 1st ed., 20-21. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991. ———. Perspectives: Historical essay, black architects - A legacy of shadows. Progressive Architecture (February, 1991). : 85-87. Adams, Walter. What america wants to build. Better Homes and Gardens 24, (June, 1946). : 23-25,96. Albrecht, Donald. World war II and the american dream: How wartime building changed a nation. Washington, DC: National Building Museum and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1995. ———. The I.S. goes hollywood... how the public learned about modern architecture. Skyline (February, 1982). : 30-31. Allen, Barbara L. The ranch-style house in america: A cultural and environmental discourse (1984-). Journal of Architectural Education 49, no. 3 (February, 1996). : 156-165. Amossy, Ruth. Autobiographies of movie stars: Presentation of self and its strategies. -

KXPR, KXJZ, KXSR, KKTO, KXJS, KQNC & KUOP Annual EEO Public File Report

KXPR, KXJZ, KXSR, KKTO, KXJS, KQNC & KUOP Annual EEO Public File Report This EEO Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following stations: KXPR-FM, KXJZ-FM, KXSR-FM, KKTO-FM, KXJS-FM, KQNC-FM and KUOP-FM all licensed to CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO. This report is placed in the public inspection files of these stations, and posted on the Website, in accordance with FCC Rules. The information contained in this Report covers the time period beginning August 2019 to and including July 2020 (the “Applicable Period”). All Full-time Vacancies filled by the Stations during the Applicable Period: 1. Accounting Manager 2. Assistant Producer, Insight 3. Interactive Producer 4. Managing Editor, News-Talk 5. Marketing Associate 6. News Reporter 7. Politics Reporter 8. Producer, Insight 9. Business Assistant 10. News Editor 11. Web Developer 12. Director of Technology The Recruitment Sources utilized to fill the above vacancies: 1. Access Sacramento, mail and email 2. Asian Resources, email 3. Auxiliary Organizations Association, website 4. CA Indian Manpower Consortium, fax 5. CA Media Jobs, listserv 6. Cal Jobs, EDD, website 7. California Association of Broadcasters, website 8. California Dept. of Rehab, email 9. California Dept. of Rehab- Auburn Office, fax 10. California Dept. of Rehab- Roseville Office, fax 11. California State University, Chico, website 12. California State University, Sacramento, website 13. Capital Public Radio, website 14. Capital Public Radio, physical bulletin board 15. Capital Public Radio Board of Directors, email 16. Capital Public Radio Facebook, website 17. Capital Public Radio LinkedIn, website 18. -

Kxpr, Kxjz, Kxsr, Kkto, Kxjs & Kqnc

KXPR, KXJZ, KXSR, KKTO, KXJS, KQNC & KUOP Annual EEO Public File Report The purpose of this EEO Public File Report (“Report”) is to comply with Section 73.2080(c) (6) of the FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule. This Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following stations: KXPR-FM, KXJZ-FM, KXSR-FM, KKTO-FM, KXJS-FM, KQNC-FM and KUOP-FM all licensed to CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO. This report is placed in the public inspection files of these stations, and posted on the Website. The information contained in this Report covers the time period beginning August 2008 to and including July 2009 (the “Applicable Period”). I. All Full-time Vacancies filled by the Stations during the Applicable Period: 1. Member Services Director 2. Member Services Coordinator II. The Recruitment Sources utilized to fill the above vacancies: (Note: Recruitment sources in bold indicate a request to be notified of vacancies.) 1. Access Sacramento, Fax #916-451-9601. 2. Western Bureau Chief NPR, (202)513-2000 3. Asian Resources, Fax #916-676-0144. 4. Bay Area Coalition, http://www.bavc.org/forum. 5. Blackbaud, Inc. www.jobsatnonprofits.com. 6. California Association of Broadcasters, www.cabroadcasters.org. 7. California Department of Rehabilitation, Sacramento District Office, Fax #916-322-0325; Elk Grove Office, Fax #916-691-1792; Sacramento NE Office, Fax #916-537-2658; South Sacramento Office, Fax #916-262- 2061; Auburn Office, Fax #530-823-4085; Roseville, Fax #916-774- 4417; Stockton, Fax #209-473-6511. 8. California Indian Manpower Consortium, Fax #916-641-6338. -

Division AA (News Staff of 16 Or More) Arts Feature First Place - KUT 90.5 FM - “SKAM Austin” Second Place - WAMU - “How to Act Sexy on Stage in the #Metoo Era”

Division AA (News Staff of 16 or more) Arts Feature First Place - KUT 90.5 FM - “SKAM Austin” Second Place - WAMU - “How To Act Sexy On Stage In The #MeToo Era” Best Collaborative Effort First Place - WNYC Radio - “Trump, Inc.” Second Place - KCUR - “Beyond The Ballot: A 5-Part Missouri-wide Series” Best Multi-Media Presentation First Place - KJZZ 91.5 FM - “Below the Rim: Life Inside the Grand Canyon” Second Place - KUOW-FM - “Transforming black pain into beauty” Best Use of Sound First Place - KERA - 90.1 Dallas - “Families Race At Texas Motor Speedway” Second Place - WLRN News - “World's Richest Race, Hometown Horse Spur Buzz” Best Writing First Place - Maine Public Broadcasting Network - “Maine's Pugnacious Governor's Complex Legacy” Second Place - KUT 90.5 FM - “ATXplained Airport Map” Breaking News First Place - WBUR - “Merrimack Valley Gas Explosions” Second Place - KCRW - “Hostages and Homage, July 21, 2018” Call-in Program First Place - WAMU - “Brett Kavanaugh And Consent Culture at Local Schools” Second Place - WNPR - Connecticut Public Radio - “The Colin McEnroe Show: Is Trump Gaslighting Us?” Commentary First Place - WFAE - “Should We Build A Wall for Gun Violence Victims” Second Place - WGBH - “The Smith College Incident and Everyday Racism” Continuing Coverage First Place - Capital Public Radio - “CapRadio Stephon Clark Coverage” Second Place - WNPR - Connecticut Public Radio - “Connecticut Public Radio: The Island Next Door” Enterprise/Investigative First Place - WNYC Radio - “NJ Jails, Suicides and Overdoses, but Little -

Go Viral 9-5.Pdf

Hello fellow musicians, artists, rappers, bands, and creatives! I’m excited you’ve decided to invest into your music career and get this incredible list of music industry contacts. You’re being proactive in chasing your own goals and dreams and I think that’s pretty darn awecome! Getting your awesome music into the media can have a TREMENDOUS effect on building your fan base and getting your music heard!! And that’s exactly what you can do with the contacts in this book! I want to encourage you to read the articles in this resource to help guide you with how and what to submit since this is a crucial part to getting published on these blogs, magazines, radio stations and more. I want to wish all of you good luck and I hope that you’re able to create some great connections through this book! Best wishes! Your Musical Friend, Kristine Mirelle VIDEO TUTORIALS Hey guys! Kristine here J I’ve put together a few tutorials below to help you navigate through this gigantic list of media contacts! I know it can be a little overwhelming with so many options and places to start so I’ve put together a few videos I’d highly recommend for you to watch J (Most of these are private videos so they are not even available to the public. Just to you as a BONUS for getting “Go Viral” TABLE OF CONTENTS What Do I Send These Contacts? There isn’t a “One Size Fits All” kind of package to send everyone since you’ll have a different end goal with each person you are contacting.