Mapping Transmembrane Binding Partners for E-Cadherin Ectodomains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New CDH3 Mutation in the First Spanish Case of Hypotrichosis with Juvenile Macular Dystrophy, a Case Report

Blanco-Kelly et al. BMC Medical Genetics (2017) 18:1 DOI 10.1186/s12881-016-0364-5 CASEREPORT Open Access New CDH3 mutation in the first Spanish case of hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy, a case report Fiona Blanco-Kelly1,2, Luciana Rodrigues-Jacy da Silva1, Iker Sanchez-Navarro1, Rosa Riveiro-Alvarez1,2, Miguel Angel Lopez-Martinez1, Marta Corton1,2 and Carmen Ayuso1,2,3* Abstract Background: CDH3 on 16q22.1 is responsible for two rare autosomal recessive disorders with hypotrichosis and progressive macular dystrophy: Hypotrichosis with Juvenile Macular Dystrophy and Ectodermal Dysplasia, Ectrodactyly and Macular Dystrophy. We present a new case of Hypotrichosis with Juvenile Macular Dystrophy. Case presentation: A Spanish male born in 1998 from non-consanguineous healthy parents with a suspected diagnosis of Keratosis Follicularis Spinulosa Decalvans and Retinitis Pigmentosa Inversa referred to our Genetics Department (IIS-Fundación Jiménez Díaz). Molecular study of ABCA4 was performed, and a heterozygous missense p.Val2050Leu variant in ABCA4 was found. Clinical revision reclassified this patient as Hypotrichosis with Juvenile Macular Dystrophy. Therefore, further CDH3 sequencing was performed showing a novel maternal missense change p.Val205Met (probably pathogenic by in silico analysis), and a previously reported paternal frameshift c.830del;p.Gly277Alafs*20, thus supporting the clinical diagnosis.. Conclusions: This is not only the first Spanish case with this clinical and molecular diagnosis, but a new mutation has been described in CDH3. Moreover, this work reflects the importance of joint assessment of clinical signs and evaluation of pedigree for a correct genetic study approach and diagnostic. Keywords: Macular dystrophy, CDH3, Hypotrichosis, Syndromic retinal dystrophy, Case report Background Dysplasia, Ectrodactyly and Macular Dystrophy (EEM, The CDH3 gene, on16q22.1, encodes for P-cadherin, OMIM: 225280) [18]. -

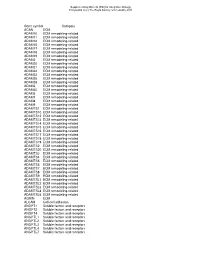

ARVC-Variants.Pdf

Updated gene list responsible for ARVC/D pathology Subtype Gene Location Reference ARVC1 TGFB3 14q24.3 Beffagna G, Occhi G, Nava A, et al. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-beta3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:366–73. ARVC2 RYR2 1q43 Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, et al. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2). Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:189–94. ARVC3 Unknown 14q12-q22 Severini GM, Krajinovic M, Pinamonti B, et al. A new locus for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia on the long arm of chromosome 14. Genomics. 1996;31:193–200. ARVC4 TTN 2q32.1-q32.3 Taylor M, Graw S, Sinagra G, et al. Genetic variation in titin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy-overlap syndromes. Circulation. 2011;124:876–85. ARVC5 TMEM43 3p25.1 Merner ND, Hodgkinson KA, Haywood AF, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:809–21. ARVC6 Unknown 10p14-p12 Li D, Ahmad F, Gardner MJ, et al. The locus of a novel gene responsible for arrhythmogenic right- ventricular dysplasia characterized by early onset and high penetrance maps to chromosome 10p12-p14. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:148–56. ARVC7 DES 2q35 Klauke B, Kossmann S, Gaertner A, et al. De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4595–607. -

Propranolol-Mediated Attenuation of MMP-9 Excretion in Infants with Hemangiomas

Supplementary Online Content Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol-mediated attenuation of MMP-9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4773 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics Protein Name Prop 12 mo/4 Pred 12 mo/4 Δ Prop to Pred mo mo Myeloperoxidase OS=Homo sapiens GN=MPO 26.00 143.00 ‐117.00 Lactotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=LTF 114.00 205.50 ‐91.50 Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MMP9 5.00 36.00 ‐31.00 Neutrophil elastase OS=Homo sapiens GN=ELANE 24.00 48.00 ‐24.00 Bleomycin hydrolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=BLMH 3.00 25.00 ‐22.00 CAP7_HUMAN Azurocidin OS=Homo sapiens GN=AZU1 PE=1 SV=3 4.00 26.00 ‐22.00 S10A8_HUMAN Protein S100‐A8 OS=Homo sapiens GN=S100A8 PE=1 14.67 30.50 ‐15.83 SV=1 IL1F9_HUMAN Interleukin‐1 family member 9 OS=Homo sapiens 1.00 15.00 ‐14.00 GN=IL1F9 PE=1 SV=1 MUC5B_HUMAN Mucin‐5B OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC5B PE=1 SV=3 2.00 14.00 ‐12.00 MUC4_HUMAN Mucin‐4 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC4 PE=1 SV=3 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 HRG_HUMAN Histidine‐rich glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=HRG 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 PE=1 SV=1 TKT_HUMAN Transketolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TKT PE=1 SV=3 17.00 28.00 ‐11.00 CATG_HUMAN Cathepsin G OS=Homo -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Nuclear Matrix Metalloproteinases: Functions Resemble the Evolution from the Intracellular to the Extracellular Compartment

OPEN Citation: Cell Death Discovery (2017) 3, 17036; doi:10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.36 Official journal of the Cell Death Differentiation Association www.nature.com/cddiscovery REVIEW Nuclear matrix metalloproteinases: functions resemble the evolution from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment Yingqiu Xie1,2,5, Aidana Mustafa1,5, Adina Yerzhan1,5, Dalmira Merzhakupova1, Perizat Yerlan1, Askarbek N Orakov1, Xiao Wang3, Yi Huang4 and Lixia Miao2 Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) is defined as an endopeptidase in the extracellular matrix (ECM), which plays essential roles in physiological processes such as organogenesis, wound healing, angiogenesis, apoptosis and motility. MMPs are produced and assembled in the cytoplasm as proenzymes with a cytoplasmic domain and require extracellular activation. MMPs can degrade receptors, extracellular matrix proteins, PARPs and release apoptotic substances. MMPs have been found in the cytosol, organelles and extracellular compartments and recently many types of MMPs have been found in the nucleus. However, the mechanisms and roles of MMPs inside the cell nucleus are still poorly understood. Here we summarized the nuclear localization mechanisms of MMPs and their functions in the nucleus such as apoptosis, tissue remodeling upon injury and cancer progression. Most importantly, we found that nuclear MMPs have evolved to translocate to membrane and target ECM possibly through evolution of nuclear localization signal (NLS), natural selection and anti-apoptotic survival. Thus, the knowledge about the evolution and regulation of nuclear MMPs appears to be essential in understanding a variety of cellular processes along with the development of MMP-targeted therapeutic drugs against the progression of certain diseases. Cell Death Discovery (2017) 3, 17036; doi:10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.36; published online 14 August 2017 KEY FACTS MMP-10, MMP-13 and MMP-14. -

Learning from Cadherin Structures and Sequences: Affinity Determinants and Protein Architecture

Learning from cadherin structures and sequences: affinity determinants and protein architecture Klára Fels ıvályi Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Klara Felsovalyi All rights reserved ABSTRACT Learning from cadherin structures and sequences: affinity determinants and protein architecture Klara Felsovalyi Cadherins are a family of cell-surface proteins mediating adhesion that are important in development and maintenance of tissues. The family is defined by the repeating cadherin domain (EC) in their extracellular region, but they are diverse in terms of protein size, architecture and cellular function. The best-understood subfamily is the type I classical cadherins, which are found in vertebrates and have five EC domains. Among the five different type I classical cadherins, the binding interactions are highly specific in their homo- and heterophilic binding affinities, though their sequences are very similar. As previously shown, E- and N-cadherins, two prototypic members of the subfamily, differ in their homophilic K D by about an order of magnitude, while their heterophilic affinity is intermediate. To examine the source of the binding affinity differences among type I cadherins, we used crystal structures, analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies. Phylogenetic analysis and binding affinity behavior show that the type I cadherins can be further divided into two subgroups, with E- and N-cadherin representing each. In addition to the affinity differences in their wild-type binding through the strand-swapped interface, a second interface also shows an affinity difference between E- and N-cadherin. -

Gene Symbol Category ACAN ECM ADAM10 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM11 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM12 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM15 E

Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is (c) The Royal Society of Chemistry 2010 Gene symbol Category ACAN ECM ADAM10 ECM remodeling-related ADAM11 ECM remodeling-related ADAM12 ECM remodeling-related ADAM15 ECM remodeling-related ADAM17 ECM remodeling-related ADAM18 ECM remodeling-related ADAM19 ECM remodeling-related ADAM2 ECM remodeling-related ADAM20 ECM remodeling-related ADAM21 ECM remodeling-related ADAM22 ECM remodeling-related ADAM23 ECM remodeling-related ADAM28 ECM remodeling-related ADAM29 ECM remodeling-related ADAM3 ECM remodeling-related ADAM30 ECM remodeling-related ADAM5 ECM remodeling-related ADAM7 ECM remodeling-related ADAM8 ECM remodeling-related ADAM9 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS1 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS10 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS12 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS13 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS14 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS15 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS16 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS17 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS18 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS19 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS2 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS20 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS3 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS4 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS5 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS6 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS7 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS8 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS9 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL1 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL2 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL3 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL4 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL5 ECM remodeling-related AGRIN ECM ALCAM Cell-cell adhesion ANGPT1 Soluble factors and receptors -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

The Urothelial Cell Line Urotsa Transformed by Arsenite and Cadmium Display Basal Characteristics Associated with Muscle Invasive Urothelial Cancers

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Pathology Faculty Publications Department of Pathology 12-14-2018 The Urothelial Cell Line UROtsa Transformed by Arsenite and Cadmium Display Basal Characteristics Associated with Muscle Invasive Urothelial Cancers Zachary E. Hoggarth Danyelle B. Osowski Brooke A. Freeberg Scott H. Garrett University of North Dakota, [email protected] Mary Ann Sens University of North Dakota, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/path-fac Recommended Citation Hoggarth, Zachary E.; Osowski, Danyelle B.; Freeberg, Brooke A.; Garrett, Scott H.; Sens, Mary Ann; Zhou, Xudong; Zhang, Ke K.; and Somji, Seema, "The Urothelial Cell Line UROtsa Transformed by Arsenite and Cadmium Display Basal Characteristics Associated with Muscle Invasive Urothelial Cancers" (2018). Pathology Faculty Publications. 1. https://commons.und.edu/path-fac/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Pathology at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pathology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Zachary E. Hoggarth, Danyelle B. Osowski, Brooke A. Freeberg, Scott H. Garrett, Mary Ann Sens, Xudong Zhou, Ke K. Zhang, and Seema Somji This article is available at UND Scholarly Commons: https://commons.und.edu/path-fac/1 RESEARCH ARTICLE The urothelial cell line UROtsa transformed by arsenite and cadmium display basal characteristics associated with muscle invasive urothelial cancers Zachary E. Hoggarth, Danyelle B. Osowski, Brooke A. Freeberg, Scott H. Garrett, Donald A. -

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary methods Human lung tissues and tissue microarray (TMA) All human tissues were obtained from the Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Tissue Bank at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). A collection of 26 lung adenocarcinomas and 24 non-tumoral paired tissues were snap-frozen and preserved in liquid nitrogen for total RNA extraction. For each tissue sample, the percentage of malignant tissue was calculated and the cellular composition of specimens was determined by histological examination (I.I.W.) following Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining. All malignant samples retained contained more than 50% tumor cells. Specimens resected from NSCLC stages I-IV patients who had no prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy were used for TMA analysis by immunohistochemistry. Patients who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were defined as smokers. Samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, stained with H&E, and reviewed by an experienced pathologist (I.I.W.). The 413 tissue specimens collected from 283 patients included 62 normal bronchial epithelia, 61 bronchial hyperplasias (Hyp), 15 squamous metaplasias (SqM), 9 squamous dysplasias (Dys), 26 carcinomas in situ (CIS), as well as 98 squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) and 141 adenocarcinomas. Normal bronchial epithelia, hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, dysplasia, CIS, and SCC were considered to represent different steps in the development of SCCs. All tumors and lesions were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2004 criteria. The TMAs were prepared with a manual tissue arrayer (Advanced Tissue Arrayer ATA100, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) using 1-mm-diameter cores in triplicate for tumors and 1.5 to 2-mm cores for normal epithelial and premalignant lesions. -

MALE Protein Name Accession Number Molecular Weight CP1 CP2 H1 H2 PDAC1 PDAC2 CP Mean H Mean PDAC Mean T-Test PDAC Vs. H T-Test

MALE t-test t-test Accession Molecular H PDAC PDAC vs. PDAC vs. Protein Name Number Weight CP1 CP2 H1 H2 PDAC1 PDAC2 CP Mean Mean Mean H CP PDAC/H PDAC/CP - 22 kDa protein IPI00219910 22 kDa 7 5 4 8 1 0 6 6 1 0.1126 0.0456 0.1 0.1 - Cold agglutinin FS-1 L-chain (Fragment) IPI00827773 12 kDa 32 39 34 26 53 57 36 30 55 0.0309 0.0388 1.8 1.5 - HRV Fab 027-VL (Fragment) IPI00827643 12 kDa 4 6 0 0 0 0 5 0 0 - 0.0574 - 0.0 - REV25-2 (Fragment) IPI00816794 15 kDa 8 12 5 7 8 9 10 6 8 0.2225 0.3844 1.3 0.8 A1BG Alpha-1B-glycoprotein precursor IPI00022895 54 kDa 115 109 106 112 111 100 112 109 105 0.6497 0.4138 1.0 0.9 A2M Alpha-2-macroglobulin precursor IPI00478003 163 kDa 62 63 86 72 14 18 63 79 16 0.0120 0.0019 0.2 0.3 ABCB1 Multidrug resistance protein 1 IPI00027481 141 kDa 41 46 23 26 52 64 43 25 58 0.0355 0.1660 2.4 1.3 ABHD14B Isoform 1 of Abhydrolase domain-containing proteinIPI00063827 14B 22 kDa 19 15 19 17 15 9 17 18 12 0.2502 0.3306 0.7 0.7 ABP1 Isoform 1 of Amiloride-sensitive amine oxidase [copper-containing]IPI00020982 precursor85 kDa 1 5 8 8 0 0 3 8 0 0.0001 0.2445 0.0 0.0 ACAN aggrecan isoform 2 precursor IPI00027377 250 kDa 38 30 17 28 34 24 34 22 29 0.4877 0.5109 1.3 0.8 ACE Isoform Somatic-1 of Angiotensin-converting enzyme, somaticIPI00437751 isoform precursor150 kDa 48 34 67 56 28 38 41 61 33 0.0600 0.4301 0.5 0.8 ACE2 Isoform 1 of Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 precursorIPI00465187 92 kDa 11 16 20 30 4 5 13 25 5 0.0557 0.0847 0.2 0.4 ACO1 Cytoplasmic aconitate hydratase IPI00008485 98 kDa 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 - 0.0081 - 0.0 -

Integrative Epigenomic and Genomic Analysis of Malignant Pheochromocytoma

EXPERIMENTAL and MOLECULAR MEDICINE, Vol. 42, No. 7, 484-502, July 2010 Integrative epigenomic and genomic analysis of malignant pheochromocytoma Johanna Sandgren1,2* Robin Andersson3*, pression examination in a malignant pheochromocy- Alvaro Rada-Iglesias3, Stefan Enroth3, toma sample. The integrated analysis of the tumor ex- Goran̈ Akerstro̊ m̈ 1, Jan P. Dumanski2, pression levels, in relation to normal adrenal medulla, Jan Komorowski3,4, Gunnar Westin1 and indicated that either histone modifications or chromo- somal alterations, or both, have great impact on the ex- Claes Wadelius2,5 pression of a substantial fraction of the genes in the in- vestigated sample. Candidate tumor suppressor 1Department of Surgical Sciences genes identified with decreased expression, a Uppsala University, Uppsala University Hospital H3K27me3 mark and/or in regions of deletion were for SE-75185 Uppsala, Sweden 2 instance TGIF1, DSC3, TNFRSF10B, RASSF2, HOXA9, Department of Genetics and Pathology Rudbeck Laboratory, Uppsala University PTPRE and CDH11. More genes were found with in- SE-75185 Uppsala, Sweden creased expression, a H3K4me3 mark, and/or in re- 3The Linnaeus Centre for Bioinformatics gions of gain. Potential oncogenes detected among Uppsala University those were GNAS, INSM1, DOK5, ETV1, RET, NTRK1, SE-751 24 Uppsala, Sweden IGF2, and the H3K27 trimethylase gene EZH2. Our ap- 4Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and proach to associate histone methylations and DNA Computational Modelling copy number changes to gene expression revealed ap- Warsaw University parent impact on global gene transcription, and en- PL-02-106 Warszawa, Poland abled the identification of candidate tumor genes for 5Corresponding author: Tel, 46-18-471-40-76; further exploration.