Mastering Malolactic Fermentation – How to Manage the Nutrition of Wine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malolactic Fermentation in Red Wine

Fact Sheet WINEMAKING Malolactic fermentation in red wine Introduction Malolactic fermentation (MLF) is a secondary bacterial fermentation carried out in most red wines. Oenococcus oeni, a member of the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) family, is the main bacterium responsible for conducting MLF, due to its ability to survive the harsh conditions of wine (high alcohol, low pH and low nutrients) and its production of desirable wine sensory attributes. One of the important roles of MLF is to confer microbiological stability towards further metabolism of L-malic acid. Specifically, MLF removes the L-malic acid in wine that can be a carbon source for yeast and bacterial growth, potentially leading to spoilage, spritz and unwanted flavours. MLF can also be conducted in some wines to influence wine style. MLF often occurs naturally after the completion of primary fermentation or can also be induced by inoculation with a selected bacterial strain. Since natural or ‘wild’ MLF can be unpredictable in both time of onset and impact on wine quality, malolactic starter cultures are commonly used. In Australia, almost all red wines undergo MLF and 74% are inoculated with bacterial starter cultures (Nordestgaard 2019). This fact sheet provides practical information for induction of MLF in red wine. A separate fact sheet provides equivalent information for white and sparkling base wine. These should also be read in conjunction with another fact sheet, Achieving successful malolactic fermentation, which gives further practical guidelines for MLF induction, monitoring and management. Updated September 2020 Fact Sheet WINEMAKING Key parameters for a successful MLF in red wine Composition of red wine/must The main wine compositional factors that determine the success of MLF are alcohol, pH, temperature and sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentration. -

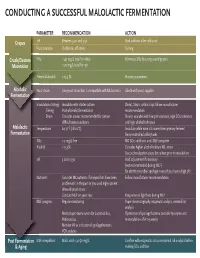

Conducting a Successful Malolactic Fermentation

CONDUCTING A SUCCESSFUL MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION PARAMETERPA RECOMMENDATION ACTION Grapes pH Between 3.20 and 3.50 Acid addition after cold soak FruitFru condition Visible rot, off odors Sorting Crush/Destem SO2SO < 40 mg/L total for white Minimize SO2 by using sound grapes Maceration < 70 mg/L total for red PotentialPPot alcohol < 13.5 % Harvest parameters Alcoholic YeastYeY a strain Use yeast strain that is compatible with ML bacteria Check with yeast supplier Fermentation InoculationIno strategy Inoculate with starter culture Direct, Step 1, or Build up: follow manufacturer Timing Post-alcoholic fermentation recommendation Strain Consider strains recommended for certain Strains available with low pH tolerance, high SO2 tolerance difficult wine conditions and high alcohol tolerance Malolactic TemperatureTem 64-71°F (18-22°C) Inoculate while wine still warm from primary ferment Fermentation Temp-controlled cellar/tanks SO2SO < 5 mg/L free NO SO2 additions until MLF complete AlcoholAlc < 13.5% Consider higher alcohol tolerant ML strain Use acclimatization steps for culture prior to inoculation pH 3.20 to 3.50 Acid adjustment if necessary (not recommended during MLF) Be alert to microbial spoilage issues if you have a high pH NNutrientsu Consider ML nutrients if vineyard lots have been Follow manufacturer recommendation problematic in the past or you used high nutrient demand yeast strain Conduct MLF on yeast lees Keep wine on light lees during MLF MMLFL progress Regular monitoring Paper chromatography, enzymatic analysis, external lab analysis Microscopic examination for Lactobacillus, If presence of spoilage bacteria consider lysozyme and Pediococcus re-inoculation after 2-3 weeks Monitor VA as indicator of spoilage bacteria PCR analysis Post Fermentation MLFML completion Malic acid < 30-50 mg/L Confirm with enzymatic assay or external lab analysis before & Aging making SO2 addition. -

Reducing Sugars in Wine

Sirromet Wines Pty Ltd 850-938 Mount Cotton Rd Mount Cotton Queensland Australia 4165 www.sirromet.com Courtesy of Jessica Ferguson Assistant Winemaker & Chemist Downloaded from seniorchem.com/eei.html Determination of Reducing Sugar Content: Clinitest, Benedict’s Solution and the Rebelein Titration Chemical Concepts and Techniques: The most important sugars present in wine and fruit juice are the hexoses - glucose and fructose. These are the sugars that yeast ferment to produce alcohol. They have the characteristic of being reducing sugars, as they contain functional groups capable of being oxidised and therefore causing reduction of other species under specific conditions. Structurally, reducing sugars must contain a free aldehyde or an alpha-hydroxy ketone capable of being oxidised. Hexose and pentose sugars in the free aldo- or keto- form or in equilibrium with these forms will fit in this category. Hexoses: Structures of Glucose: Structures of Fructose: Pentoses: The five carbon pentoses are also classified as reducing sugars and may contribute as much as 28% of the residual reducing sugar content of a dry table wine. Pentoses in wine include ribose, arabinose and rhamnose. Most are not fermentable by yeast (although some can be utilised by bacteria). Example of pentose structure (Ribose): Hexoses and pentoses share the quality of existing in aqueous solution in two or more different forms (cyclic and non-cyclic) in equilibrium. The non-cyclic is the least common but it is present in small amounts in the wine or juice matrix. In alkaline solution sugars undergo decyclisation to yield the corresponding non-cyclic aldo- and keto- forms. -

Château Simone

Château Simone This historic estate, situated in the hills just south of Aix-en-Provence, has been in the hands of four generations of the Rougier family since 1830 and holds a virtual monopoly on the appellation of Palette. The property totals 120 hectares, with 28 under vine, of which 23 qualify for the Palette AOC. Its vineyards sit on limestone soils at elevations between 500 and 750 feet on the slopes of the Montaiguet, whose special microclimate is influenced by the encircling pine forests, the mass of the Mont Sainte-Victoire, and the Arc River. The vineyards were reconstituted after phylloxera and many vines are over a century old. In an industry that moves quicker than ever and presents ever-increasing novelty, an estate like Simone is an anchor of meaning and a lens into Provence's patrimony. Viticulture: • Farming: Ecocert Organic Certification Pending. Viticulture has always been practicing organic. • Treatments : No herbicides, chemical fertilizers, or synthetic treatments • Ploughing: Extensive ploughing and working of the soil by tractor. • Soils: Limestone Scree • Vines: Head-trained vines, many over 100-years old, that are replanted on a vine-by-vine basis to maintain a healthy vineyard • Yields: Old vines and extensive debudding lower yields and eliminate the need for a green harvest. • Harvest: Entirely manual harvest, grapes sorted in the vineyard and sorted again in the cellar • Purchasing: Always entirely estate fruit Vinification: Aging: • Fermentation: All wines are fermented spontaneously in large • Élevage: Palette wines are stored in foudres for 18 months; wooden foudres with temperature control for 2 weeks. red and white wines spend an additional year in neutral barrel. -

Influence of the Ph of Chardonnay Must on Malolactic Fermentation In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by JKI Open Journal Systems (Julius Kühn-Institut) Vitis 45 (4), 197–198 (2006) Research Note plicate using a volume of 100 l for each trial. Commer- cial strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lalvin Rhône Influence of the pH of Chardonnay 4600 and of Oenococcus oeni, Lalvin 31, were prepared according to the manufacture instructions. Bacteria were must on malolactic fermentation in- inoculated 16 h after the yeast inoculation when total and free SO were 28.0 and 6.4 mg·l-1, respectively. The fer- duced by bacteria co-inoculated with 2 mentations were monitored by analysis of ethanol produc- yeasts tion, L-malic acid consumption, yeast and bacteria cell concentrations. After AF, commercial MLF nutrient (Opti G. ZAPPAROLI1), E. TOSI2) and S. KRIEGER3) Malo Plus, Lallemand) was added according to the manu- facture instructions. Total acidity, sugars, ethanol, sulfite 1) Dipartimento Scientifico e Tecnologico, Università degli Studi and pH were determined using standard methods, organic di Verona, Verona, Italy acids were quantified using enzyme kits (Roche). Eight 2) Centro per la Sperimentazione in Vitivinicoltura, Provincia di biogenic amine (BA) (histamine, cadaverine, putrescine, Verona, Servizio Agricoltura, San Floriano, Verona, Italy phenylethylalanine, amylamine, isobutylamine, methyl- 3) Lallemand, office Korntal-Münchingen, Germany amine and isopropylamine) were determined as previously described (TORREA and ANCIN 2001). Data are average of K e y w o r d s : malolactic fermentation, yeast-bacteria two determinations. Cell counts were carried out plating co-inoculation, Chardonnay wine. on WL agar (Oxoid) medium for yeasts and MRS (Fluka) added 10 % tomato juice and 0.01 % actidione (Fluka) for Introduction: In wine, the success of the malolactic bacteria. -

Analytical Methods in Wineries: Is It Time to Change?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository Publisher: TAYLOR & FRANCIS INC, 325 CHESTNUT ST, SUITE 800, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19106 USA Subject Category: Food Science & Technology; Nutrition & Dietetics Website: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all?content=10.1081/FRI-200051897 ISSN: 8755-9129 Analytical Methods in Wineries: Is It Time to Change? M. D. LUQUE DE CASTRO,1 J. GONZÁLEZ-RODRÍGUEZ,2 AND P. PÉREZ-JUAN3 1Department of Analytical Chemistry, Campus of Rabanales, Córdoba, Spain 2Southampton Oceanography Centre, George Deacon Division, Waterfront Campus, European Way, Southampton, United Kingdom 3LIEC, Polígono Industrial, Manzaranes Ciudad Real, Spain A review of the methods for the most common parameters determined in wine—namely, ethanol, sulfur dioxide, reducing sugars, polyphenols, organic acids, total and volatile acidity, iron, soluble solids, pH, and color—reported in the last 10 years is presented here. The definition of the given parameter, official and usual methods in wineries appear at the beginning of each section, followed by the methods reported in the last decade divided into discontinuous and continuous methods, the latter also are grouped in nonchromatographic and chromatographic methods because of the typical characteristics of each subgroup. A critical comparison between continuous and discontinuous methods for the given parameter ends each section. Tables summarizing the features of the methods and a conclusions section may help users to select the most appropriate method and also to know the state-of-the-art of analytical methods in this area. Keywords Parameters, Official methods, Usual methods, Non chromatographic methods, Chromatographic methods Wine is a product with a very complex composition. -

Simultaneous Analysis of Sugars and Organic Acids in Wine and Grape Juices T by HPLC: Method Validation and Characterization of Products from Northeast Brazil

Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 66 (2018) 160–167 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Food Composition and Analysis journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jfca Original research article Simultaneous analysis of sugars and organic acids in wine and grape juices T by HPLC: Method validation and characterization of products from northeast Brazil Emanuela Monteiro Coelhoa, Carla Valéria da Silva Padilhaa, Gabriela Aquino Miskinisa, Antônio Gomes Barroso de Sáa, Giuliano Elias Pereirab, Luciana Cavalcanti de Azevêdoa, ⁎ Marcos dos Santos Limaa, a Instituto Federal do Sertão Pernambucano, Departamento de Tecnologia em Alimentos, Campus Petrolina, Rod. BR 407 Km 08, S/N, Jardim São Paulo, CEP 56314-520, Petrolina, PE, Brazil b Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária – Embrapa Semiárido/Uva e Vinho, Rodovia BR 428, Km 152, CP 23, CEP 56302-970 Petrolina, PE, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Organic acids and sugars are related to the chemical balance of wines and grape juices, besides exerting a strong Food analysis influence on the taste balance and sensorial acceptance by consumers. The aim of this study was to validate a Food composition method for the simultaneous determination of sugars and organic acids in wines and grape juices by high- Vitis labrusca L performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with refractive index detection (RID) and diode array detection Beverage analysis (DAD) and to characterize commercial products from northeast Brazil. The method provided values for linearity Wine − (R > 0.9982), precision (CV% < 1.4), recovery (76–106%) and limits of detection (0.003–0.044 g L 1) and Grape juice fi – −1 Sparkling wine quanti cation (0.008 0.199 g L ) which are considered acceptable for application in the characterization of Sugars these types of matrices. -

Study of the Chemical Composition, the Antioxidant Activity and the Organoleptic Profile of Bulgarian Wines from Hybrid Grape Varieties

Original scientific paper DOI: /10.5513/JCEA01/20.4.2358 Journal of Central European Agriculture, 2019, 20(4), p.1201-1209 Study of the chemical composition, the antioxidant activity and the organoleptic profile of Bulgarian wines from hybrid grape varieties Проучване на химичния състав, антиоксидантната активност и органолептичния профил на български вина от хибридни сортове Tatyana YONCHEVA1 (✉), Eva IVANIŠOVA2, Attila KÁNTOR2 1 Institute of Viticulture and Enology, 5800 Pleven, Bulgaria, str. Kala tepe 1. Department of Vine-Selection, Enology and Chemistry 2 Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia, Tr. A. Hlinku 2. Faculty of Biotechnology and Food Sciences, Department of Plant Storage and Processing ✉ Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The chemical composition, the antioxidant activity and the organoleptic profile of Bulgarian wines from the hybrid varieties Misket Kaylashki, Rubin, Kaylashki Rubin and Trapezitsa was studied. The properties of the red wines were compared to those of Cabernet Sauvignon wine. The varieties were grown in the region of Pleven, Central Northern Bulgaria. The results had shown that the wine composition was mainly determined by the variety and its peculiarities. Misket Kaylashki white wine had the lowest rate of sugar-free extract and total acidity. From the red wines, Rubin contained the highest sugar-free extract and glycerol, Kaylashki Rubin had the lowest concentration of glycerol and the highest total acidity, Trapezitsa had the lowest sugar-free extract. In the red wines, the rate of total phenolic compounds and anthocyanins was highest in Rubin and the lowest in Trapezitsa. Misket Kaylashki, as a typical muscat wine, had the highest rates of esters. -

Practical High-Acidity Winemaking Strategies for the Midwest

PRACTICAL HIGH-ACIDITY WINEMAKING STRATEGIES FOR THE MIDWEST DREW HORTON, ENOLOGY SPECIALIST UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA GRAPE BREEDING & ENOLOGY PROJECT GETTING STARTED •A BASIC UNDERSTANDING OF PH AND TOTAL ACIDITY IS INVALUABLE TO PRACTICAL WINE MAKING. PH VS. TA (TOTAL ACIDITY) • BOTH ARE A MEASURE OF THE RELATIVE STRENGTH OF ACIDITY IN WINE, BUT THEY DO NOT CORRELATE EXACTLY. • PH: THE INVERSE LOG OF HYDROGEN IONS IN A SOLUTION • PH: A LOGARITHMIC SCALE FROM 0 TO 14 • A PH OF 3.0 IS 10X HIGHER (OR “STRONGER”) THAN A PH OF 4.0. • TYPICALLY A PH BETWEEN 3.1 AND 3.6 IS DESIRABLE FOR WINE. PH VS. TA (TOTAL ACIDITY) • TOTAL ACIDITY IS AN EMPIRICAL MEASUREMENT OF ALL OF THE ACIDS IN A SOLUTION, OFTEN GIVEN IN GRAMS/LITER. • THE HIGHER THE ACIDITY, THE MORE TART A WINE WILL TASTE. • PH IS ABOUT MICROBIAL STABILITY, MOUTH FEEL, STRUCTURE, AND AGE-ABILITY OF A GIVEN WINE. • PH IS QUALITATIVE ACIDITY. TOTAL ACIDITY IS QUANTITATIVE… “… THE BEST THING FOR A VINEYARD ARE THE FOOTPRINTS OF THE WINEMAKER…” WINE IS MADE IN THE VINEYARD FIRST!!! • WINEMAKING STARTS IN THE VINEYARD. • VITICULTURAL PRACTICES AND HARVEST TIMING HAVE MAJOR EFFECTS • ACTIVE COLLABORATION BETWEEN VITICULTURIST AND WINEMAKER • VITICULTURE AND ENOLOGY ARE “TWO WINGS OF THE SAME BIRD”… • KNOWLEDGE OF ALL COLD-CLIMATE VARIETIES WILL HELP TO MAKE BALANCED WINES FROM THESE CHALLENGING VARIETIES. POST-VÉRAISON SUGAR/ACID CURVE ACIDS AND PH CHANGES •THROUGHOUT RIPENING, AS ACIDITY DECREASES, PH INCREASES… DETERMINING RIPENESS, AND WHEN TO PICK? RIPENESS IS MORE THAN A NUMBER. • AROMA AND FLAVOR • TEXTURE AND COLOR • CONDITION, OF VINEYARD, VINE, STEM, CLUSTER, BERRY, SKIN AND SEED… • OVERALL HEALTH, CROP LOAD, PEST ACTIVITY AND DISEASES • IMPENDING WEATHER AND PICKING CREW/MACHINERY AVAILABILITY USE THE LAB IN YOUR MOUTH AND NOSE. -

Malolactic Fermentation in Wine La Fermentation

MMALOLACTICALOLACTIC FFERMENTATIONERMENTATION IINN WWINEINE LLAA FFERMENTATIONERMENTATION MMALOLACTIQUEALOLACTIQUE DDUU VVININ LLAA FFERMENTACIÓNERMENTACIÓN MMALOLÁCTICAALOLÁCTICA DDELEL VVINOINO LLAA FFERMENTAZIONEERMENTAZIONE MMALOLATTICAALOLATTICA DELDEL VVINOINO BBIOLOGISCHERIOLOGISCHER SSÄUREABBAUÄUREABBAU ININ WEINWEIN AAPPEL-MELKSUURGISTINGPPEL-MELKSUURGISTING IINN WWYNYN A FFERMENTAÇÃOERMENTAÇÃO MMALOLÁCTICAALOLÁCTICA DDOO VINHOVINHO MMALOLAKTIALOLAKTICCNAˇ NA FFERMENTACIJAERMENTACIJA VINAVINA MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION IN WINE UNDERSTANDING THE SCIENCE AND THE PRACTICE Magali Bou (France) Piet Loubser (Republic of South Africa) Dr. Neil Brown (U.S.A.) Dr. Rich Morenzoni (U.S.A.) Dr. Peter Costello (Australia) Dr. Antonio Palacios (Spain) Dr. Richard Degré (Canada) Dr. Chris Powell (United Kingdom) Wilfried Dieterich (Germany) Katie Scully Specht (U.S.A.) Sigrid Gertsen-Briand (Canada) Gordon Specht (U.S.A.) Samantha Kollar (U.S.A.) Didier Theodore (France) Dr. Sibylle Krieger (Germany) Dr. Sylvie Van Zandycke (Belgium) Annamarie Kyne (U.S.A.) Scientifi c Editor: Dr. Rich Morenzoni Managing Editor: Katie Scully Specht Published by OCTOBER 2005 ii MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION IN WINE Production Coordinator: Claude Racine Copy editing: Judith Brown Designer: François Messier Printing: Les Impressions Au Point Certain research published or cited in this publication was funded in whole or in part by Lallemand Inc. DISCLAIMER Lallemand has compiled the information contained herein and, to the best of its knowledge, the information is true and -

Chardonnay Grape Guide By

Brehm Vineyards’ Chardonnay Grape Wine Guide v1.1 Copyright © 2011 by Peter Brehm. Not to be reprinted in any form. There Introduction are many ways to produce these styles of wine. Your Chardonnay Guide is for 20 liters of The methods described herein are personal, pressed and settled Chardonnay grape juice based on classic winemaking techniques that from one of three different vintages. The have been proven over decades. It is the way Chardonnay juices are from the White Peter Brehm, our winemaker, wishes to guide Salmon Vineyard in the Pacific Northwest’s you through this production of fine wine - it is Columbia Gorge AVA. Each of these vintage not the only way – Peter is still learning. juices will benefit from adjustment. Grape Juice Fermentation Chardonnay not only reflects the geographical Grape juice fermentation refers to the region and particular site where grown, it is a conversion of grape juice into wine by the canvas upon which the winemakers can freely actions of yeast reproduction. Brehm express their style and preferences. A Vineyards® provides you with your Chardonnay in the Chablis style is crisp, winemaking starting point and that is White fermented dry without malolactic Salmon Vineyard’s Chardonnay juice. fermentation. It is fresh and clean with little to no oak flavoring. A Burgundy style chardonnay Yeast are single celled organisms that, under usually is fermented in the presence of oak, anaerobic conditions (oxygen-free aged on the lees with much lees stirring environments), can use sugar as a carbon (batonnage). Chardonnay in the Burgundy source to grow and divide. -

Saccharomyces Cerevisiae in the Production of Fermented Beverages

beverages Review Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the Production of Fermented Beverages Graeme M Walker 1,* and Graham G Stewart 2 1 Abertay University, Dundee, Scotland DD1 1HG, UK 2 Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland EH14 4AS, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1382-308658 Academic Editor: Edgar Chambers IV Received: 20 October 2016; Accepted: 11 November 2016; Published: 17 November 2016 Abstract: Alcoholic beverages are produced following the fermentation of sugars by yeasts, mainly (but not exclusively) strains of the species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The sugary starting materials may emanate from cereal starches (which require enzymatic pre-hydrolysis) in the case of beers and whiskies, sucrose-rich plants (molasses or sugar juice from sugarcane) in the case of rums, or from fruits (which do not require pre-hydrolysis) in the case of wines and brandies. In the presence of sugars, together with other essential nutrients such as amino acids, minerals and vitamins, S. cerevisiae will conduct fermentative metabolism to ethanol and carbon dioxide (as the primary fermentation metabolites) as the cells strive to make energy and regenerate the coenzyme NAD+ under anaerobic conditions. Yeasts will also produce numerous secondary metabolites which act as important beverage flavour congeners, including higher alcohols, esters, carbonyls and sulphur compounds. These are very important in dictating the final flavour and aroma characteristics of beverages such as beer and wine, but also in distilled beverages such as whisky, rum and brandy. Therefore, yeasts are of vital importance in providing the alcohol content and the sensory profiles of such beverages. This Introductory Chapter reviews, in general, the growth, physiology and metabolism of S.