Saccharomyces Cerevisiae in the Production of Fermented Beverages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microbial Enzymes and Their Applications in Industries and Medicine

BioMed Research International Microbial Enzymes and Their Applications in Industries and Medicine Guest Editors: Periasamy Anbu, Subash C. B. Gopinath, Arzu Coleri Cihan, and Bidur Prasad Chaulagain Microbial Enzymes and Their Applications in Industries and Medicine BioMed Research International Microbial Enzymes and Their Applications in Industries and Medicine Guest Editors: Periasamy Anbu, Subash C. B. Gopinath, Arzu Coleri Cihan, and Bidur Prasad Chaulagain Copyright © 2013 Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in “BioMed Research International.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Contents Microbial Enzymes and Their Applications in Industries and Medicine,PeriasamyAnbu, Subash C. B. Gopinath, Arzu Coleri Cihan, and Bidur Prasad Chaulagain Volume 2013, Article ID 204014, 2 pages Effect of C/N Ratio and Media Optimization through Response Surface Methodology on Simultaneous Productions of Intra- and Extracellular Inulinase and Invertase from Aspergillus niger ATCC 20611, Mojdeh Dinarvand, Malahat Rezaee, Malihe Masomian, Seyed Davoud Jazayeri, Mohsen Zareian, Sahar Abbasi, and Arbakariya B. Ariff Volume 2013, Article ID 508968, 13 pages A Broader View: Microbial Enzymes and Their Relevance in Industries, Medicine, and Beyond, Neelam Gurung, Sumanta Ray, Sutapa Bose, and Vivek Rai Volume 2013, Article -

Sweet Molasses Bread Recipe Source: Yield: 2-3 Loaves

Sweet Molasses Bread Recipe Source: www.melskitchencafe.com Yield: 2-3 loaves Ingredients: 2 ½ cups warm water (about 110°) 1 ½ Tbsp instant yeast 5 Tbsp molasses 2 Tbsp unsweetened, natural cocoa powder 3 Tbsp canola oil 5 Tbsp honey 2 tsp salt 3 Tbsp vital wheat gluten (optional, but it will make the bread lighter and softer) 4 cups white whole wheat flour 2-3 cups all-purpose flour (use bread flour if not using the wheat gluten) 1 Tbsp butter Steps: . In the bowl of an electric stand mixer fitted with a dough hook (or in a large bowl with a wooden spoon if making by hand), combine the water, yeast, molasses, cocoa, honey, salt, gluten (if using), and 2 cups of the whole wheat flour. Mix until combined. With the mixer running, slowly add 1 more cup of whole wheat flour. Start adding the remaining whole wheat flour then the white flour gradually until the dough pulls away from the sides of the bowl. Knead for 7-10 minutes (about 15 if kneading by hand). The dough should be soft and slightly tacky but shouldn’t leave much residue on your fingers if you grab a piece. Turn dough into a large, lightly oiled bowl, cover with greased plastic wrap or light towel. Let rise until doubled. Lightly punch down the dough and divide into three equal pieces. Form into tight oval loaves and place on lightly greased baking sheets (use two baking sheets to avoid crowding bread). Lightly cover with greased plastic wrap or a light towel. -

Brewing Yeast – Theory and Practice

Brewing yeast – theory and practice Chris Boulton Topics • What is brewing yeast? • Yeast properties, fermentation and beer flavour • Sources of yeast • Measuring yeast concentration The nature of yeast • Yeast are unicellular fungi • Characteristics of fungi: • Complex cells with internal organelles • Similar to plants but non-photosynthetic • Cannot utilise sun as source of energy so rely on chemicals for growth and energy Classification of yeast Kingdom Fungi Moulds Yeast Mushrooms / toadstools Genus > 500 yeast genera (Means “Sugar fungus”) Saccharomyces Species S. cerevisiae S. pastorianus (ale yeast) (lager yeast) Strains Many thousands! Biology of ale and lager yeasts • Two types indistinguishable by eye • Domesticated by man and not found in wild • Ale yeasts – Saccharomyces cerevisiae • Much older (millions of years) than lager strains in evolutionary terms • Lot of diversity in different strains • Lager strains – Saccharomyces pastorianus (previously S. carlsbergensis) • Comparatively young (probably < 500 years) • Hybrid strains of S. cerevisiae and wild yeast (S. bayanus) • Not a lot of diversity Characteristics of ale and lager yeasts Ale Lager • Often form top crops • Usually form bottom crops • Ferment at higher temperature o • Ferment well at low temperatures (18 - 22 C) (5 – 10oC) • Quicker fermentations (few days) • Slower fermentations (1 – 3 weeks) • Can grow up to 37oC • Cannot grow above 34oC • Fine well in beer • Do not fine well in beer • Cannot use sugar melibiose • Can use sugar melibiose Growth of yeast cells via budding + + + + Yeast cells • Each cell is ca 5 – 10 microns in diameter (1 micron = 1 millionth of a metre) • Cells multiply by budding a b c d h g f e Yeast and ageing - cells can only bud a certain number of times before death occurs. -

WINE YEAST: the CHALLENGE of LOW TEMPERATURE Zoel Salvadó Belart Dipòsit Legal: T.1304-2013

WINE YEAST: THE CHALLENGE OF LOW TEMPERATURE Zoel Salvadó Belart Dipòsit Legal: T.1304-2013 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Screening of Indigenous Yeast from Different Ecological Regions of Kathmandu Valley and Its Application in Wine Production

Screening of Indigenous Yeast From Different Ecological Regions of Kathmandu Valley and Its Application in Wine Production Bipanab Rajopadhyaya1, Bipana Maharjan1, Roshani Maharjan1, Amrit Acharya1 1 Department Microbiology, Pinnacle College, Affi liated Tribhuvan University, Lalitpur, Nepal Corresponding author: Amrit Acharya, [email protected], ph: 9849180693, Department of Microbiology, Pinnacle College, Affi liated Tribhuvan University, Lalitpur, Nepal University ABSTRACT Objectives: The aim of the study was to isolate and screen the potent yeast from the air for implementing new yeast in wine fermentation. Methods: In this study, 35 air samples collected in sterile grape juice in glass jar and left over for four days exposure for the growth of yeast from different locations around the Kathmandu Valley. Yeasts were screened by culturing on selective Ethanol Sulfi te Agar (ESA) media at 30°C for 2-3 days in Microbiology Lab of Pinnacle College. Yeast isolates were characterized based on colony morphology, microscopic characteristics, Fermentative capacity, Hydrogen sulfi de production. Selected yeast isolates were subjected to ethanol fermentation and tested for alcohol tolerance capacity. Wine quality was assessed by sensory evaluation. Results: Of 35 samples, only 20 yeast isolates were isolated. Among these isolates, the variation in colony characteristics along with oval and ellipsoidal microscopic appearance was observed. All the isolates were able to ferment major sugars such as glucose, fructose and sucrose, but few could not ferment galactose and maltose, while none-fermented lactose and xylose. Here, isolates showing no H2S (L29, L34) and mild H2S producer (isolate L31) were subjected to ethanol fermentation. Also, Comparative analysis was made by using commercial standard wine yeast (STAN). -

Basic Definitions and Tips for Winemaking

Presque Isle Wine Cellars “Serving the Winemaker Since 1964” (814) 725-1314 www.piwine.com Basic Winemaking Terms & Tips Definitions & Tips: Not all-inclusive but hopefully helpful. Email us your favorites; maybe we’ll include them in the next edition. Acid Reduction - Reducing the acid in juice or wine to an acceptable level. It is usually measured as tartaric acid and requires a testing apparatus and reagents. Good levels are typically in a range of 0.6 to 0.8 percent acid, depending on the wine. More technically the reading is read as grams per liter. Therefore 0.6 percent would be 6.0 g/l. Acidulation or Acidification - Raising the acid level of juice, wine or sometimes water by adding some type of acid increasing additive or blending with a higher acid juice or wine. Acidified or Acidulated Water - Water to which acid (most commonly citric acid) has been added. It is a way to reduce sugar in a juice that is too high in sugar without diluting (thus reducing) the acid level of that juice. Additives - Things added to wine to enhance quality or possibly fix some type of flaw. There are many additives for many situations and it is wise to gain at least some basic knowledge in this area. Alcohol - Obviously one of the significant components of wine. Yeast turns sugar to alcohol. Rule of thumb says for each percentage of sugar in a non-fermented juice, the alcohol will be half. For example 21% sugar should ferment out to an alcohol level of about 11.5 to 12%. -

Free Amino Nitrogen in Brewing

fermentation Review Free Amino Nitrogen in Brewing Annie E. Hill * and Graham G. Stewart International Centre for Brewing & Distilling, Heriot-Watt University, Riccarton, Edinburgh EH14 4AS, Scotland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1314513458 Received: 22 January 2019; Accepted: 13 February 2019; Published: 18 February 2019 Abstract: The role of nitrogenous components in malt and wort during the production of beer has long been recognized. The concentration and range of wort amino acids impact on ethanolic fermentation by yeast and on the production of a range of flavour and aroma compounds in the final beer. This review summarizes research on Free Amino Nitrogen (FAN) within brewing, including various methods of analysis. Keywords: brewing; fermentation; free amino nitrogen; wort; yeast 1. Introduction The earliest written account of brewing dates from Mesopotamian times [1]. However, our understanding of the connection with yeast is relatively recent, starting with Leeuwenhoek’s microscope observations in the 17th century followed by the work of Lavoisier, Gay-Lussac, Schwann and others during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was not until the late 19th century that Pasteur demonstrated that fermented beverages result from the action of living yeast’s transformation of glucose (and other sugars) into ethanol [2–4]. Since then, our knowledge has expanded exponentially, particularly with the development of molecular biology techniques [5]. In this review, we cover the particular contribution that wort nitrogen components play in beer production during fermentation. A number of terms are used to define wort nitrogenous components: Free Amino Nitrogen (FAN) is a measure of the nitrogen compounds that may be assimilated or metabolised by yeast during fermentation. -

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Formation in Bread As a Function of Heat Treatment Intensity: Correlations with Browning Indices

foods Article 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Formation in Bread as a Function of Heat Treatment Intensity: Correlations with Browning Indices Gabriella Giovanelli and Carola Cappa * Dipartimento di Scienze per gli Alimenti, la Nutrizione e l’Ambiente, Università degli Studi di Milano, Via G. Celoria, 2-20133 Milano, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-025-0319-179; Fax: +39-503-19-190 Abstract: 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) is formed during bread baking as a Maillard reaction product (MRP); it can exert toxicity and it is regarded as a potential health risk because of its high consumption levels in western diets. The aim of this study was to evaluate HMF formation in bread as a function of heat treatment intensity (HTI) and to investigate correlations between HMF and easily detectable browning indices. White breads were baked at 200 ◦C and 225 ◦C for different baking times for a total of 24 baking trials. Browning development was evaluated by reflectance colorimetric and computer vision colour analysis; MRP were quantified spectrophotometrically at 280, 360 and 420 nm and HMF was determined by HPLC. HMF concentrations varied from 4 to 300 mg/kg dw. Colour indices (100–L*) and Intensity mean resulted significantly correlated between each other (r = −0.961) and with MRP (r ≥ 0.819). The effects of the different HTI were visualized by principal component analysis and the data were used to evaluate the best fitting regression models between HMF concentration and other browning indices, obtaining models with high correlation coefficients (r > 0.90). Citation: Giovanelli, G.; Cappa, C. Keywords: bread; Maillard reaction products; HMF; browning; colour; regression models 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Formation in Bread as a Function of Heat Treatment Intensity: Correlations with Browning Indices. -

The Alcohol Textbook 4Th Edition

TTHEHE AALCOHOLLCOHOL TEXTBOOKEXTBOOK T TH 44TH EEDITIONDITION A reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries Edited by KA Jacques, TP Lyons and DR Kelsall Foreword iii The Alcohol Textbook 4th Edition A reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries K.A. Jacques, PhD T.P. Lyons, PhD D.R. Kelsall iv T.P. Lyons Nottingham University Press Manor Farm, Main Street, Thrumpton Nottingham, NG11 0AX, United Kingdom NOTTINGHAM Published by Nottingham University Press (2nd Edition) 1995 Third edition published 1999 Fourth edition published 2003 © Alltech Inc 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publishers. ISBN 1-897676-13-1 Page layout and design by Nottingham University Press, Nottingham Printed and bound by Bath Press, Bath, England Foreword v Contents Foreword ix T. Pearse Lyons Presient, Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA Ethanol industry today 1 Ethanol around the world: rapid growth in policies, technology and production 1 T. Pearse Lyons Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA Raw material handling and processing 2 Grain dry milling and cooking procedures: extracting sugars in preparation for fermentation 9 Dave R. Kelsall and T. Pearse Lyons Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA 3 Enzymatic conversion of starch to fermentable sugars 23 Ronan F. -

Malolactic Fermentation in Red Wine

Fact Sheet WINEMAKING Malolactic fermentation in red wine Introduction Malolactic fermentation (MLF) is a secondary bacterial fermentation carried out in most red wines. Oenococcus oeni, a member of the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) family, is the main bacterium responsible for conducting MLF, due to its ability to survive the harsh conditions of wine (high alcohol, low pH and low nutrients) and its production of desirable wine sensory attributes. One of the important roles of MLF is to confer microbiological stability towards further metabolism of L-malic acid. Specifically, MLF removes the L-malic acid in wine that can be a carbon source for yeast and bacterial growth, potentially leading to spoilage, spritz and unwanted flavours. MLF can also be conducted in some wines to influence wine style. MLF often occurs naturally after the completion of primary fermentation or can also be induced by inoculation with a selected bacterial strain. Since natural or ‘wild’ MLF can be unpredictable in both time of onset and impact on wine quality, malolactic starter cultures are commonly used. In Australia, almost all red wines undergo MLF and 74% are inoculated with bacterial starter cultures (Nordestgaard 2019). This fact sheet provides practical information for induction of MLF in red wine. A separate fact sheet provides equivalent information for white and sparkling base wine. These should also be read in conjunction with another fact sheet, Achieving successful malolactic fermentation, which gives further practical guidelines for MLF induction, monitoring and management. Updated September 2020 Fact Sheet WINEMAKING Key parameters for a successful MLF in red wine Composition of red wine/must The main wine compositional factors that determine the success of MLF are alcohol, pH, temperature and sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentration. -

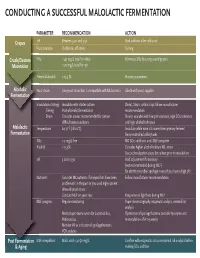

Conducting a Successful Malolactic Fermentation

CONDUCTING A SUCCESSFUL MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION PARAMETERPA RECOMMENDATION ACTION Grapes pH Between 3.20 and 3.50 Acid addition after cold soak FruitFru condition Visible rot, off odors Sorting Crush/Destem SO2SO < 40 mg/L total for white Minimize SO2 by using sound grapes Maceration < 70 mg/L total for red PotentialPPot alcohol < 13.5 % Harvest parameters Alcoholic YeastYeY a strain Use yeast strain that is compatible with ML bacteria Check with yeast supplier Fermentation InoculationIno strategy Inoculate with starter culture Direct, Step 1, or Build up: follow manufacturer Timing Post-alcoholic fermentation recommendation Strain Consider strains recommended for certain Strains available with low pH tolerance, high SO2 tolerance difficult wine conditions and high alcohol tolerance Malolactic TemperatureTem 64-71°F (18-22°C) Inoculate while wine still warm from primary ferment Fermentation Temp-controlled cellar/tanks SO2SO < 5 mg/L free NO SO2 additions until MLF complete AlcoholAlc < 13.5% Consider higher alcohol tolerant ML strain Use acclimatization steps for culture prior to inoculation pH 3.20 to 3.50 Acid adjustment if necessary (not recommended during MLF) Be alert to microbial spoilage issues if you have a high pH NNutrientsu Consider ML nutrients if vineyard lots have been Follow manufacturer recommendation problematic in the past or you used high nutrient demand yeast strain Conduct MLF on yeast lees Keep wine on light lees during MLF MMLFL progress Regular monitoring Paper chromatography, enzymatic analysis, external lab analysis Microscopic examination for Lactobacillus, If presence of spoilage bacteria consider lysozyme and Pediococcus re-inoculation after 2-3 weeks Monitor VA as indicator of spoilage bacteria PCR analysis Post Fermentation MLFML completion Malic acid < 30-50 mg/L Confirm with enzymatic assay or external lab analysis before & Aging making SO2 addition. -

Saccharomyces Eubayanus, the Missing Link to Lager Beer Yeasts

MICROBE PROFILE Sampaio, Microbiology 2018;164:1069–1071 DOI 10.1099/mic.0.000677 Microbe Profile: Saccharomyces eubayanus, the missing link to lager beer yeasts Jose Paulo Sampaio* Graphical abstract Ecology and phylogeny of Saccharomyces eubayanus. (a) The ecological niche of S. eubayanus in the Southern Hemisphere – Nothofagus spp. (southern beech) and sugar-rich fructifications (stromata) of its fungal biotrophic parasite Cyttaria spp., that can attain the size of golf balls. (b) Schematic representation of the phylogenetic position of S. eubayanus within the genus Saccharomyces based on whole-genome sequences. Occurrence in natural environments (wild) or participation in different human-driven fermentations is highlighted, together with the thermotolerant or cold-tolerant nature of each species and the origins of S. pastorianus, the lager beer hybrid. Abstract Saccharomyces eubayanus was described less than 10 years ago and its discovery settled the long-lasting debate on the origins of the cold-tolerant yeast responsible for lager beer fermentation. The largest share of the genetic diversity of S. eubayanus is located in South America, and strains of this species have not yet been found in Europe. One or more hybridization events between S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae ale beer strains gave rise to S. pastorianus, the allopolyploid yeasts responsible for lager beer production worldwide. The identification of the missing progenitor of lager yeast opened new avenues for brewing yeast research. It allowed not only the selective breeding of new lager strains, but revealed also a wild yeast with interesting brewing abilities so that a beer solely fermented by S. eubayanus is currently on the market.