Survival & Lila Downs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lila Downs LA CANTINA “Entre Copa Y Copa...”

Lila Downs LA CANTINA “entre copa y copa...” Exploring and expressing Mexico's rich culture has been a lifelong passion for Lila Downs. La Cantina: “Entre Copa y Copa...” marks a unique turn in her career path, as she focuses intently on the rich and familiar repertoire of Mexico's beloved cancion ranchera tradition. The cancion ranchera is typically a ballad about heartache, solitude, love and longing — a song such as one would typically hear in a local cantina. It is a musical tradition quite akin to Portugal’s fado, or to the Delta blues — deeply soulful, often lamenting, always emotionally vivid. Downs and her partner, multi-instrumentalist Paul Cohen reflect, “Our new album brings out smiles and complicity from every person in the audience. After all, who doesn't like to go out to a bar, have some drinks and cry to your favorite songs?.... Well, maybe not everyone cries, but we can all remember — as we say in Spanish: ‘I'm not crying. It’s that cigarette smoke making my eyes burn....’" Special guest Flaco Jimenez, the legendary Tejano accordionist, brings his rootsy norteño sound to the mix. In the hands of Lila and her band, this historic repertoire is handled with a hip, contemporary edge that surely draws from her residency in the great melting pot of New York City in recent years — a world away from her dual upbringing in Minnesota and the Sierra Madre mountains of Oaxaca. Living in such varied environments, Downs took after her mother’s stage career by singing mariachi tunes at age 8. -

The Lookout Vol 3 2016

THE LOOKOUT Volume 3 | Spring 2016 THE LOOKOUT A Journal of Literature and the Arts by the students of Texas A&M University-Central Texas Volume 3 | Spring 2016 Copyright 2016 | THE LOOKOUT Texas A&M University-Central Texas The Lookout: A Journal of Literature and the Arts features student works and is published annually by the College of Arts and Sciences at Texas A&M University-Central Texas, Killeen, Texas. Editor, Layout, and Cover Design - Ryan Bayless Assistant Lecturer of English and Fine Arts Special thanks to Dr. Allen Redmon, Chair of the Department of Humanities, and Dr. Jerry Jones, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at TAMUCT. Contents THE LOOKOUT Volume 3 | Spring 2016 Poetry SHARON INCLE Lonely Star ............................................. 9 BETTY LATHAM Bernice ................................................. 10 TIM DEOCARIZA In Grey Manila .................................... 11 CHAD PETTIT The Mourning, After .......................... 12 REBECCA BRADEN Desolation ........................................... 21 RACHEL HART Birthday Party-Oahu, March 1945 .. 22 MIKAYLA MERCER In the Presence of the Divine ............ 25 MICHAEL HERMANN Little Girl ............................................. 26 DWIGHT A. GRAY Villanelle for Charleston .................... 27 TAMMI SUMMERS Moving Forward ................................. 28 WILLIAM HODGES In Heideggerian Time ........................ 39 AMBER CELESTE MCENTIRE Blood Moon ........................................ 41 HEATHER CHANDLER Southern Comfort ............................. -

Bacalao Bio.Pages

MEMBERS: Pablo Estacio, voice and bass Julio Andrade, sax, wind controller, backing vocals Germán Quintero, drums, backing vocals Luis González, guitar Rolando González, samples, electronic, percussion, coros DOWNLOADS: High-res Images | Band Logo Technical Rider Stage Layout NEW ALBUM SANGRE ¡SONGO, PSICODELIA Y RELEASE DATE: MAY 2018 CONNECT WITH US: bacalaomen.com BUGALÚ! Spotify | YouTube instagram.com/bacalaomen facebook.com/bacalaomen Booking: [email protected] ABOUT Bacalao Men was born in Caracas in 1999, when Pablo Estacio asked two musician friends to form a songo band. The group first featured Sebastián Araujo on drums, Aurelio Martínez on sax, and Pablo Estacio on bass and vocal. Within the first jam sessions, the musical structures and atmosphere that would give Bacalao its essence began to emerge, with its intelligent lyrics, afrolatin beats with jolts of funk, hip hop and electronic. The formation soon was enriched with the integration of DJ Hernia; Vladimir Rivero, Caracas’ legendary salsa percussionist, and Rafael Gómez, former guitarist of Lapamariposa and currently performing with Lila Downs. With its new members, and an undeniably original repertoire, Bacalao embarked on its first era of concerts in different Caracas venues and all throughout Venezuela, quickly generating a buzz about its indisputably new yet familiar sound. El Nuevo Bugalú (2005) was its second album, also produced independently. El Nuevo Bugalú concentrated on small chronicles told by song, and with it, the group expanded its sounds characterized by the use of native semantics of the city of Caracas, religion, love, and stress. From this second album came the group’s hits Malibu and El Comegente, a cheeky chronicle that relates the life of Dorángel Vargas, a cannibal who devoured over a dozen people in the 90’s.Through El Nuevo Bugalú, Bacalao was awarded Best Album of the Year, Best Song (El Comegente) and Best Production (Bacalao Men) by Venezuela’s Foundation of New Bands (Fundación Nuevas Bandas). -

Media and Social Media Links

Booking Contact: Tonatl Music LLC [email protected] Cel: 503‐496‐2075 Edna Vazquez is fearless singer, songwriter and guitarist whose powerful voice and musical talent embrujan and transcend the boundaries of language to engage and uplift her audience. She is a creative crisol with a vocal range that allows her to paint seamlessly with her original material, an intersection of folk, rock, pop and R&B. Edna’s passion for music and performance grew from her bicultural raices and, with songs deeply rooted in universal human emotion, she has traveled far and wide spreading her message of light, love and cultural healing. Media and Social Media Links www.ednavazquez.com www.ednavazquez.com/video www.facebook.com/ednavazquezmusic www.ednavazquez.bandcamp.com www.youtube.com/ednavazquezmusic www.youtube.com/watch?v=JfxxfwV‐_K8 www.youtube.com/watch?v=RDORJNv2IOk&t=3288s Edna is currently performing Solo and with her band in support of her most recent release, Sola Soy, and writing new music for an album to be released in 2019. The Edna Vazquez Band features William Seiji Marsh on lead guitar (Lost Lander, Cherry Poppin Daddies), Gil Assayas on keys (GLASYS), Milo Fultz on bass and upright bass 3 Leg Torso, and Jesse Brooke on drums and percussion (Trio Subtonic). “Extraordinarily talented” ‐ Hungton Post “Her powerful voice is the centerpiece of whatever she does” ‐ Willamette Week “Completely original and wildly inventive” ‐ Next Northwest Venues Edna has performed: Lincoln Center, The Kennedy Center Millenium Stage, MGM Grand (Latin Grammy -

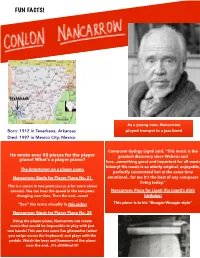

Activity Sheet

FUN FACTS! As a young man, Nancarrow Born: 1912 in Texarkana, Arkansas played trumpet in a jazz band Died: 1997 in Mexico City, Mexico Composer György Ligeti said, “This music is the He wrote over 50 pieces for the player greatest discovery since Webern and piano! What’s a player piano? Ives...something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, The Entertainer on a player piano perfectly constructed but at the same time Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 21 emotional...for me it’s the best of any composer living today.” This is a canon in two parts (see p. 6 for more about canons). You can hear the speed in the two parts Nancarrow: Piece for Ligeti (for Ligeti’s 65th changing over time. Then the end...wow! birthday) “See” the score visually in this video This piece is in his “Boogie-Woogie style” Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 25 Using the player piano, Nancarrow can create music that would be impossible to play with just two hands! This one has some fun glissandos (when you swipe across the keyboard) and plays with the pedals. Watch the keys and hammers of the piano near the end...it’s aliiiiiiive!!!!! 1 FUN FACTS! Population: 130 million Capital: Mexico City (Pop: 9 million) Languages: Spanish and over 60 indigenous languages Currency: Peso Highest Peak: Pico de Orizaba volcano, 18,491 ft Flag: Legend says that the Aztecs settled and built their capital city (Tenochtitlan, Mexico City today) on the spot where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a snake. -

2020 Musical Event of the Year “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” (Feat

FOR YOUR CMA CONSIDERATION ENTERTAINER OF THE YEAR FEMALE VOCALIST OF THE YEAR SINGLE OF THE YEAR SONG OF THE YEAR MUSIC VIDEO OF THE YEAR “BLUEBIRD” #1 COUNTRY RADIO AIRPLAY HIT OVER 200 MILLION GLOBAL STREAMS ALBUM OF THE YEAR WILDCARD #1 TOP COUNTRY ALBUMS DEBUT THE BIGGEST FEMALE COUNTRY ALBUM DEBUT OF 2019 & 2020 MUSICAL EVENT OF THE YEAR “FOOLED AROUND AND FELL IN LOVE” (FEAT. MAREN MORRIS, ELLE KING, ASHLEY MCBRYDE, TENILLE TOWNES & CAYLEE HAMMACK) “We could argue [Lambert’s] has been the most important country music career of the 21st century” – © 2020 Sony Music Entertainment ENTERTAINER ERIC CHURCH “In a Music Row universe where it’s always about the next big thing – the hottest new pop star to collaborate with, the shiniest producer, the most current songwriters – Church is explicitly focused on his core group and never caving to trends or the fleeting fad of the moment.” –Marissa Moss LUKE COMBS “A bona fide country music superstar.” –Rolling Stone “Let’s face it. Right now, it’s Combs’ world, and we just live in it.” –Billboard “Luke Combs is the rare exception who exploded onto the scene, had a better year than almost anyone else in country music, and is only getting more and more popular with every new song he shares.” –Forbes MIRANDA LAMBERT “The most riveting country star of her generation.” –NPR “We could argue [Lambert’s] has been the most important country music career of the 21st century.” –Variety “One of few things mainstream-country-heads and music critics seem to agree on: Miranda Lambert rules.” –Nashville Scene “The queen of modern country.” –Uproxx “.. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

Graduate Commencement Ceremony 2020.Indd

Graduate Commencement Ceremony Saturday, July 11, 2020 20 6:00pm CET 20 Order of Events Call to Order and Commencement Greetings María Martínez Iturriaga Executive Director, Valencia Campus Greetings from President Roger H. Brown Roger H. Brown President Greetings from the Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Lawrence J. Simpson Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Provost Interim Dean of Academic Affairs / Faculty Speaker Jeanine Cowen Interim Dean of Academic Affairs Student Speaker Sharon Onyango-Obbo Degree Candidate, M.M. in Music Production Technology Innovation Nairobi, Kenya Video Salute to the Class of 2020 Presentation of the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music Lila Downs Tribute Performance “La Cumbia Del Mole” Commencement Speaker Lila Downs Graduate Student Awards and Conferral of Degrees, Class of 2020 Magdalini Giannikou Program Director, Master of Music in Contemporary Performance (Production Concentration) Emilien Moyon Program Director, Master of Arts in Global Entertainment and Music Business Pablo Munguía Program Director, Master of Music in Music Production, Technology, and Innovation Lucio Godoy Program Director, Master of Music in Scoring for Film, Television, and Video Games Introduction of Candidates Catalina Millán Assistant Professor, Liberal Arts Department Pete Dyson Associate Professor, Global Entertainment and Music Business Processional and Recessional Talon - Abøn Together- Tati Rabell Like You Are - Delia Joyce Changes - Celestine & Earlybird Strange Bulería - Alba Haro Up High - Jimena Wu -

Mexican Sentimiento and Gender Politics A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Corporealities of Feeling: Mexican Sentimiento and Gender Politics A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Lorena Alvarado 2012 © Copyright by Lorena Alvarado 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Corporealities of Feeling: Mexican Sentimiento and Gender Politics by Lorena Alvarado Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2011 Professor Alicia Arrizón, co-chair Professor Susan Leigh Foster, co-chair This dissertation examines the cultural and political significance of sentimiento, the emotionally charged delivery of song in ranchera genre musical performance. Briefly stated, sentimiento entails a singer’s fervent portrayal of emotions, including heartache, yearning, and hope, a skillfully achieved depiction that incites extraordinary communication between artist and audience. Adopting a feminist perspective, my work is attentive to the elements of nationalism, gender and sexuality connected to the performance of sentimiento, especially considering the genre’s historic association with patriotism and hypermasculinity. I trace the logic that associates representations of feeling with nation-based pathology and feminine emotional excess and deposits this stigmatized surplus of affect onto the singing body, particularly that of the mexicana female singing body. In this context, sentimiento is represented in film, promotional material, and other mediating devices as a bodily inscription of personal and gendered tragedy, ii as the manifestation of exotic suffering, or as an ancestral and racial condition of melancholy. I examine the work of three ranchera performers that corroborate these claims: Lucha Reyes (1906-1944), Chavela Vargas (1919) and Lila Downs (1964). -

Historic Structure Report: Scruggs-Briscoe Cabin, Elkmont Historic District, Great Smoky Mountains National Park List of Figures

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Elkmont Historic District Great Smoky Mountains National Park Scruggs-Briscoe Cabin Elkmont Historic District Great Smoky Mountains National Park Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science Division Southeast Region Scruggs-Briscoe Cabin Elkmont Historic District Great Smoky Mountains National Park Historic Structure Report March 2016 Prepared by The Jaeger Company Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science Division TheThe cultural report presentedlandscape here report exists presented in two formats. here exists A printed in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, theversion Southeastern is available Regional for study Office at the of park, the Nationalthe Southeastern Park Service,Regional and Office at a variety of the ofNational other repositories.Park Service, Forand atmore a variety widespread access, this cultural landscape report also exists of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the Nationalalso exists Park in Service.a web-based Please format visit through www.nps.gov Integrated for Resource more information. Management Applications (IRMA). Please visit www.irma. nps.gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science Division Southeast Regional Office Cultural Resources National Park Service Southeast Region 100 Alabama Street, SW National Park Service Atlanta, Georgia 30303 100 Alabama St. SW (404)507-5847 Atlanta, GA 30303 (404) 562-3117 Great Smoky Mountains National Park 107 Park Headquarters Road Gatlinburg, TN 37738 2006www.nps.gov/grsm CulturalAbout the cover: Landscape View of theReport Scruggs-Briscoe Cabin, 2015 Doughton Park and Sections 2A, B, and C Blue Ridge Parkway Asheville, NC Scruggs-Briscoe Cabin Elkmont Historic District Great Smoky Mountains National Park Historic Structure Report Approved By. -

20 Ticks, Mites, Mold, Fungi

CHAPTER 20 THE BEST CONTROL FOR TICKS, MITES, MOLD AND FUNGI 859 Developmental Stages of the American Dog Tick Ticks are bloodsucking parasites that are often found in tall grass and brush. There are more than 850 species of ticks worldwide, at least 100 can and do transmit more than 65 diseases. For photographs and Quick Time movies of several tick species click on the tick image gallery at: http://www.ent.iastate.edu/imagegal/ticks/. Many tick-borne diseases often go undiagnosed because they mimic Lyme disease and its flu-like symptoms. They include: babesiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Colorado tick fever, tularemia and ehrlichiosis. It is very likely that a person can be bitten once and become infected with more than one agent. Ticks are literally living cesspools that suck blood and diseases from a variety of animals before they finally die. The tick’s mouthparts are designed for sucking blood and holding on to the host at the same time. Most ticks prefer to feed on animals, but when they are hungry and you walk by, watch out. The two common ticks in the U.S.A. are the Lone Star Tick and the American Dog Tick. An estimated 1% of tick populations can carry Colorado tick fever or Rocky Mountain spotted fever (primarily in the western and eastern U. S.) Ticks can be found in the woods, lawns, meadows, shrubs, weeds, caves, homes and cabins. Wear medicated body powder or food-grade DE mixed in menthol or diluted geranium oil and/or Safe Solutions Insect Repellent to try to repel them. -

BRT Past Schedule 2011

Join Our Mailing List! 2011 Past Schedule current schedule 2015 past schedule 2014 past schedule 2013 past schedule 2012 past schedule 2010 past schedule 2009 past schedule 2008 past schedule JANUARY THANK YOU! Despite the still-challenging economy, Blackstone River Theatre saw more than 6,100 audience members attend nearly 100 concerts, dances, classes and private functions in 2010! September marked the 10-year anniversary of the reopening of Blackstone River Theatre after more than four years of volunteer renovation efforts from July, 1996, to September, 2000. Since reopening, BRT has now presented more than 1,050 events in front of more than 67,000 audience members! Look for details about another six-week round of fiddle classes for beginner, continuing beginner/intermediate, advanced intermediate and advanced students with Cathy Clasper-Torch beginning Jan. 25 and Jan. 26. Look for details about six-week classes in beginner mountain dulcimer and clogging with Aubrey Atwater starting Jan. 13. Look for details about six-week classes in beginner mandolin and also playing tunes on mandolin with Ben Pearce starting Jan. 24. There will be an exhibit called "Through the Lens: An Exploration in Digital Photography" by Kristin Elliott-Stebenne and Denise Gregoire in BRT's Art Gallery January 14 through Feb. 19. There will be an exhibit opening Saturday, Jan. 15 from 6-7:30 p.m. NOTE: If a show at BRT has an advance price & a day-of-show price it means: If you pre-pay OR call in your reservation any time before the show date, you get the advance price.