Interspecific Competition and Social Behavior in Violet-Green Swallows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violet-Green Swallow

Breeding Habitat Use Profile Habitats Used in Arizona Primary: Montane Riparian Secondary: Montane Forests, locally Upper Sonoran Desert Key Habitat Parameters Plant Composition Most montane forest types, often with some element of riparian, wetland, open water or 8 other moist habitat types Plant Density and Unknown Size Violet-green Swallow, photo by ©George Andrejko Microhabitat Snags, live trees, or cliffs for nesting, mesic Features areas with high insect productivity for forag- Conservation Profile ing 8; in wooded landscapes, often noted foraging and nesting near forest clearings Species Concerns and edges. Climate Change (Droughts) Increasing Fire Frequency Landscape Largely unknown, but must include some Timber Harvesting Practices old-growth forests or cliffs Conservation Status Lists Elevation Range in Arizona USFWS 1 No 3,200 – 10,500 feet, locally to 1,200 feet 9 AZGFD 2 No Density Estimate DoD 3 No Territory Size: Unknown BLM 4 No Density: Unknown, sometimes occurs in loose colonies 8 PIF Watch List 5b No PIF Regional Concern 5a No Migratory Bird Treaty Act Natural History Profile Covered Seasonal Distribution in Arizona PIF Breeding Population Size Estimates 6 Breeding April – early August, desert nesting may Arizona 710,000 ◑ begin in March 9 Global 7,200,000 ◑ Migration February – April; August – mid-October 9 9.93% Percent in Arizona Winter Rare, very small numbers 5b PIF Population Goal Nest and Nesting Habits Maintain 8 Type of Nest Cavity or crevice Trends in Arizona Nest Substrate Tree, rock, or cliff; also artificial -

Monochromatic: Red Orange Yellow Green Blue Violet Complementary

Monochromatic: Split Complementary: Red Red, Yellow-Green, Blue-Green Orange Red-Orange, Green, Blue Yellow Orange, Blue-Green, Blue-Violet Green Yellow-Orange, Blue, Violet Blue Yellow, Blue-Violet, Red-Violet Violet Yellow-Green, Violet, Red Green, Red-Violet, Red-Orange Complementary: Blue-Green, Red, Orange Red & Green Blue, Red-Orange, Yellow-Orange Red-Orange & Blue-Green Blue-Violet, Orange, Yellow Orange & Blue Violet, Yellow-Orange, Yellow-Green Yellow-Orange & Blue-Violet Red-Violet, Yellow, Green Yellow & Violet Yellow-Green & Red-Violet Tetradic: Red, Yellow, Green, Violet Triadic: Red, Yellow-Orange, Green, Blue-Violet Red, Yellow, Blue Red-Orange, Blue-Green, Yellow-Orange, Blue- Red-Orange, Yellow-Green, Blue-Violet Violet Orange, Green, Violet Red-Orange, Blue-Green, Yellow, Violet Yellow-Orange, Blue-Green, Red-Violet Orange, Blue, Green, Red Orange, Blue, Yellow-Green, Red-Violet Analogous: Yellow-Orange, Blue-Violet, Green, Red Red, Red Orange, Orange Yellow, Violet, Blue, Orange Red-Orange, Orange, Yellow-Orange Yellow-Green, Red-Violet, Blue-Green, Red- Orange, Yellow-Orange, Yellow Orange Yellow-Orange, Yellow, Yellow-Green Yellow, Yellow-Green, Green Yellow-Green, Green, Blue-Green Green, Blue-Green, Blue Blue-Green, Blue, Blue-Violet Blue, Blue-Violet, Violet Blue-Violet, Violet, Red-Violet Violet, Red-Violet, Red Red-Violet, Red, Red-Orange . -

Violet Red Bile Agar M049

Violet Red Bile Agar M049 Violet Red Bile Agar is selective medium used for the isolation, detection and enumeration of coli-aerogenes bacteria in water, milk, other dairy food products and also from clinical samples. Composition** Ingredients Gms / Litre Peptic digest of animal tissue 7.000 Yeast extract 3.000 Sodium chloride 5.000 Bile salts mixture 1.500 Lactose 10.000 Neutral red 0.030 Crystal violet 0.002 Agar 15.000 Final pH ( at 25°C) 7.4±0.2 **Formula adjusted, standardized to suit performance parameters Directions Suspend 41.53 grams in 1000 ml distilled water. Heat with stirring to boiling to dissolve the medium completely. DO NOT AUTOCLAVE. Cool to 45°C and pour into sterile Petri plates containing the inoculum. If desired, the medium can be sterilized by autoclaving at 15 lbs pressure at 15lbs pressure (121°C) for 15 minutes. Principle And Interpretation The coliform group consists of several genera of bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae . The historical definition of this group has been based on the method used for detection i.e. lactose fermentation. This group is defined as all aerobic and facultative anaerobic, gram-negative, non-spore-forming rod shaped bacteria that ferment lactose with gas and acid formation within 48 hour at 35°C (1, 2). Examination of foods, ingredients and raw materials, for the presence of marker groups such as coliforms is the one of the common tests. Violet Red Bile Agar, a modification of MacConkeys original formulation (3) is used for the enumeration of coli-aerogenes bacterial group. -

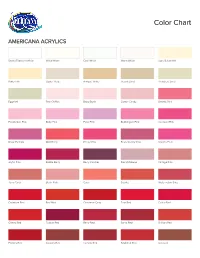

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

BWSR Featured Plant: Downy Yellow Violet

2019 June Plant of the Month BWSR Featured Plant Name: Downy yellow violet (Viola pubescens) Plant family: Violet (Violaceae) Downy yellow Downy yellow violet, AKA hairy yellow violets are an important early violet or smooth yellow violet, is food source for a short (4- to 12-inch-tall), native, pollinators. Fine hairs along the herbaceous perennial that blooms in rounded teeth woodlands, gardens edge of the leaf are a distinguishing and shady areas Plant Stats feature. Brown lines starting in April. It STATEWIDE on the flower petals provides an early lead pollinators to WETLAND nectar and pollen. splash of color and INDICATOR Photo Credits: important early STATUS: FACU Heather Holm season nectar and PRIMARY USES: pollen. Like other Ground cover, shade/pollinator Viola species, this gardens, edibles, plant produces both woodland showy, open cross- restorations pollinating flowers at the top of the plant, and fully closed, self-pollinating flowers that may be found aboveground or underground. The showy flowers bloom before trees leaf out. The closed flowers bloom once the tree canopy leafs out. Planting Recommendations Range Downy yellow violets and can be used as Downy yellow violet is found may not be as an alternative to turf throughout Minnesota. Records aggressive as some grass, along paths and exist in all but a handful of other violets in a woodland borders, counties. It is mostly found east garden, but will spread and can be mixed with of the Missouri River, with a few over time in ideal other short woodland records west of the Missouri. conditions — part plants such as sedges, Its range stretches into New shade and medium to anemones and wild England and north into central dry soils. -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

Why Is the Sky Purple?

A laboratory experiment from the Why is Little Shop of Physics at Colorado State University the sky CMMAP purple? Reach for the sky. Overview Necessary materials: Of course, you expect the question to be “why is the sky blue?” That’s the classic version. • 1 “sunset egg” • A white light flashlight And here’s the classic answer: scattering. We’ll talk about what this word means and how it leads to sky color, but we will also see that the The most crucial piece for this experiment is the light from the sky actually contains a bit more “sunset egg.” The small-scale structure of these violet than it does blue! So why do we see glori- glass “eggs” works well to demonstrate the differ- ous blue skies rather than a purple firmament ential scattering that leads to the color of the sky when we gaze up into Earth’s atmosphere? and the color of the sunset. Theory You can find them at rock and nature shops, or you can purchase them in bulk from Pelham Grayson The first person to correctly work out the de- (www.pelhamgrayson.com) under “Magic Feng tails of the process that gives rise to the color of Shui Eggs”. the sky was the English physicist, Lord John Rayleigh, working in the late 1800’s. Rayleigh correctly surmised that the blue color of the sky was a result of scattering. As light enters our atmosphere on its journey from the sun, it interacts with air molecules and is redirected. This redirection is more pronounced for shorter wavelengths toward the blue, or violet, end of the spectrum. -

The Electromagnetic Spectrum CESAR’S Booklet

The electromagnetic spectrum CESAR’s Booklet The electromagnetic spectrum The colours of light You have surely seen a rainbow, and you are probably familiar with the explanation to this phenomenon: In very basic terms, sunlight is refracted as it gets through water droplets suspended in the Earth’s atmosphere. Because white light is a mixture of six (or seven) different colours, and each colour is refracted a different angle, the result is that the colours get arranged in a given order, from violet to red through blue, green, yellow and orange. We can get the same effect in a laboratory by letting light go through a prism, as shown in Figure 1. This arrangement of colours is what we call a spectrum. Figure 1: White light passing through a prism creates a rainbow. (Credit: physics.stackexchange.com) Yet the spectrum of light is not only made of the colours we see with our eyes. There are other colours that are invisible, although they can be detected with the appropriate devices. Beyond the violet, we have ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. On the other extreme, beyond the red, we have infrared and radio. Although we cannot see them, we are familiar with these other types of light: for example, we use radio waves to transmit music from one station to our car receiver, ultraviolet light from the Sun makes our skin get tanned, X-rays are used by radiography machines to check if we have a broken bone, or we change channel in our TV device by sending an infrared signal to it from the remote control. -

Name: Edhelper the Electromagnetic Spectrum

Name: edHelper The Electromagnetic Spectrum Look around you. What do you see? You might say "people, desks, and papers." What you really see is light bouncing off people, desks, and papers. You can only see objects if they reflect light (or produce it). Think about it- if the room were in total darkness, would you still be able to see the people, desks, and papers? No. We see light as brightness or the opposite of darkness. Light is a type of energy made by the vibration of electrically charged particles. What we call light is just part of this energy. Scientists call light electromagnetic radiation. Some sources of light are the sun, other stars, and fire. We can feel heat from the sun and fire. We can't feel the heat from stars because they are too far away, but they do make heat just as our sun, also a star, does. Light transfers energy in the forms of light and heat. Light transfers energy in other forms that are harder to detect. The sun produces a huge amount of energy. The energy the sun produces travels in little particles called photons. There are different kinds of energy produced by the sun. Some light we can see, just a tiny part of it, called visible light. Other types of light energy are invisible. There are different wavelengths of light, or really, we should call it electromagnetic radiation or EM for short. Other types of EM are very long radio waves and very short wavelengths like x-rays and gamma rays. -

The Relationship Between Wavelength and Frequency in the Electromagnetic Spectrum

Name_______________________________________ The Relationship Between Wavelength and Frequency in the Electromagnetic Spectrum Purpose: To discover and verify the relationship between Wavelength and Frequency of the Electromagnetic Spectrum. Background Information: Visible light is Electromagnetic radiation at wavelengths which the human eye can see. We perceive this radiation as colors ranging from red (longer wavelengths; ~ 700 nanometers) to violet (shorter wavelengths; ~400 nanometers.) The visible light from the Sun is actually composed of the colors red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet, which can become distinguishable when sunlight passes through a prism. A good way to remember the order of the colors is to note that the first letters of the colors spell out the name ROY G. BV. We can think of light traveling in waves with properties of wavelength and frequency. Wavelength is the distance between identical locations on adjacent waves (see figure below). Frequency is the number of complete waves, or wavelengths, that pass a given point each second. All light travels at the same speed, but each color has a different wavelength and frequency. It is their different wavelengths that cause the different colors of light to separate and become visible when passing through a prism. Look at the illustration of the visible spectrum above. Can you guess which color has the longest wavelength? It's red! The wavelengths of the other colors decrease in order, with violet light having the shortest. Adapted from: http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/teachers/lessons/roygbiv/roygbiv.html Before you start: Summarize the graphic on the electromagnetic spectrum shown below. Think about the relationships in and among the various wavelengths and the position of each type of radiation in the electromagnetic spectrum. -

Color Names Defined by SAS/GRAPH

Appendix C: Color Names Defined by SAS/GRAPH Introduction .............................................................................................. 219 Basic Hues ................................................................................................ 220 Blacks ....................................................................................................... 220 Blues ......................................................................................................... 221 Browns ...................................................................................................... 222 Grays ......................................................................................................... 223 Greens ...................................................................................................... 224 Olives ........................................................................................................ 226 Oranges ..................................................................................................... 226 Pinks ......................................................................................................... 227 Purples ...................................................................................................... 228 Reds .......................................................................................................... 229 Violets ....................................................................................................... 229 Whites ...................................................................................................... -

The Electromagnetic Spectrum the Electromagnetic Spectrum the EM Spectrum Is the ENTIRE Range of EM Waves in Order of Increasing Frequency and Decreasing Wavelength

The Electromagnetic Spectrum The Electromagnetic Spectrum The EM spectrum is the ENTIRE range of EM waves in order of increasing frequency and decreasing wavelength. As you go from left right, the wavelengths get smaller and the frequencies get higher. This is an inverse relationship between wave size and frequency. (As one goes up, the other goes down.) This is because the speed of ALL EM waves is the speed of light (300,000 km/s). Things to Remember The higher the frequency, the more energy the wave has. EM waves do not require media in which to travel or move. EM waves are considered to be transverse waves because they are made of vibrating electric and magnetic fields at right angles to each other, and to the direction the waves are traveling. Inverse relationship between wave size and frequency: as wavelengths get smaller, frequencies get higher. The Waves (in order…) Radio waves: Have the longest wavelengths and the lowest frequencies; wavelengths range from 1000s of meters to .001 m Used in: RADAR, cooking food, satellite transmissions Infrared waves (heat): Have a shorter wavelength, from .001 m to 700 nm, and therefore, a higher frequency. Used for finding people in the dark and in TV remote control devices Visible light: Wavelengths range from 700 nm (red light) to 30 nm (violet light) with frequencies higher than infrared waves. These are the waves in the EM spectrum that humans can see. Visible light waves are a very small part of the EM spectrum! Visible Light Remembering the Order ROY G. BV red orange yellow green blue violet Ultraviolet Light: Wavelengths range from 400 nm to 10 nm; the frequency (and therefore the energy) is high enough with UV rays to penetrate living cells and cause them damage.