Preplanetary Nebulae: an HST Imaging Survey and a New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIR High-Resolution Imaging and Radiative Transfer Modeling of the Frosty Leo Nebula

Planetary Nebulae in our Galaxy and Beyond Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 234, 2006 c 2006 International Astronomical Union M. J. Barlow & R. H. M´endez, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921306003802 NIR high-resolution imaging and radiative transfer modeling of the Frosty Leo nebula K. Murakawa1, K. Ohnaka1, T. Driebe1, K.-H. Hofmann1, D. Schertl1,S.Oya2, and G. Weigelt1 1Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, D-53121 Bonn, Germany email: [email protected] 2Subaru telescope, 650 North A’ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA Abstract. We present a K-band speckle image and HK-band polarimetric images of the proto- planetary nebula Frosty Leo obtained using the 6 m SAO telescope and the 8 m Subaru telescope, respectively. Our speckle image revealed clumpy structures in the hourglass-like bipolar nebula. The polarimetric data, for the first time, detected an elongated region with small polarizations and polarization vector alignment on the east side of the central star. We have performed radiative transfer calculations to model the dust shell of Frosty Leo. We found that micron-size grains in the equatorial dense region and small grains in the bipolar lobes are required to explain the total intensity images, the polarization images, and the spectral energy distribution. Keywords. speckle imaging, polarimetry, radiative transfer modeling, Frosty Leo, PPN 1. Introduction Frosty Leo is a well-studied oxygen-rich proto-planetary nebula (PPN). The deep wa- ter ice absorption feature at 3.1 µm(τ3.1µm∼3.3) was detected in the L-band spectrum (Rouan et al. -

The Evolutionary Status of the Frosty Leo Nebula

Asymmetrical Planetary Nebulae II: From Origins to Microstructures ASP Conference Series, Vol. 199, 2000 J.H. Kastner, N. Soker, & S. Rappaport, eds. The evolutionary status of The Frosty Leo Nebula Tyler Bourke1, A. R. Hyland2, Garry Robinson3, & Kevin Luhman1 1Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge MA, USA 2Southern Cross University, Lismore NSW, Australia 3University College, UNSW-ADFA, Canberra ACT, Australia Abstract. We present new observational data for IRAS 09371+1212, the Frosty Leo Nebula, in the form of infrared spectra from 2.2–2.5µm which reveal photospheric bands of CO. The 12CO/13CO band ratio deter- mined is similar to those exhibited by evolved K giant stars, and supports the proposal that the object is highly evolved. The equivalent width of the CO bands implies, however, that the spectral type lies in the range G5III to K0III, somewhat earlier than K7III, as derived from colours and optical spectra. The smaller equivalent widths of the CO bands may re- flect a low metal abundance which could fit well with the considerable height of the source above the galactic plane (>0.9kpc). 1. Introduction The Frosty Leo Nebula, IRAS 09371+1212, remains unique with its extremely deep 3.1µm absorption feature, almost two decades in depth, its twin far-infrared emission features at 44 and 62µm, and its abnormal location, >0.9kpc from the plane of the Galaxy. Forveille et al. (1987; hereafter FMOL) concluded, primarily on the basis of its 2.6mm CO emission spectrum, that it is a post-AGB star with a bipolar circumstellar envelope, and suggested water ice mantles around the grains as the source of the excess emission in the 60µm IRAS band. -

Title a Self-Consistent Photoionization-Dust

A self-consistent photoionization-dust continuum-molecular line Title transfer model of NGC 7027 Author(s) Volk, K; Kwok, S Citation The Astrophysical Journal, 1997, v. 477 n. 2 pt. 1, p. 722-731 Issued Date 1997 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/179686 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License THE ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL, 477:722È731, 1997 March 10 ( 1997. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. A SELF-CONSISTENT PHOTOIONIZATIONÈDUST CONTINUUMÈMOLECULAR LINE TRANSFER MODEL OF NGC 7027 KEVIN VOLK AND SUN KWOK Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4 Received 1996 June 20; accepted 1996 September 23 ABSTRACT A model to simulate the entire spectrum (1000Ó to 1 cm) of the high-excitation young planetary nebula NGC 7027 is presented. The ionized, dust, and molecular components of the object are modeled using geometric parameters obtained from visible, radio, infrared, and CO data. The physical processes considered include recombination lines of H and He, collisional excited lines of metals, bf and † contin- uum radiations, two-photon radiation, dust continuum radiation, and molecular rotational and vibra- tional transitions. The dust component is assumed to be heated by a combination of direct starlight and the line and continuum radiation from the ionized nebula. The molecular component of the nebula is coupled to the dust component through the stimulated absorption of the dust continuum radiation. Spe- ciÐcally, we compare the predicted Ñuxes of the CO rotational lines and the 179.5 km water rotational line to those observed by the Infrared Space Observatory satellite. -

A Massive Bipolar Outflow and a Dusty Torus with Large Grains in the Preplanetary Nebula Iras 22036+5306 R

The Astrophysical Journal, 653:1241Y1252, 2006 December 20 # 2006. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. A MASSIVE BIPOLAR OUTFLOW AND A DUSTY TORUS WITH LARGE GRAINS IN THE PREPLANETARY NEBULA IRAS 22036+5306 R. Sahai,1 K. Young,2 N. A. Patel,2 C. Sa´nchez Contreras,3 and M. Morris4 Received 2006 June 19; accepted 2006 August 10 ABSTRACT We report high angular resolution (100)COJ ¼ 3Y2 interferometric mapping using the Submillimeter Array (SMA) of IRAS 22036+5306 (I22036), a bipolar preplanetary nebula (PPN) with knotty jets discovered in our HST snapshot survey of young PPNs. In addition, we have obtained supporting lower resolution (1000) CO and 13CO J ¼ 1Y0 observations with the Owens Valley Radio Observatory (OVRO) interferometer, as well as optical long-slit echelle spectra at the Palomar Observatory. The CO J ¼ 3Y2 observations show the presence of a very fast (220 km sÀ1), 39 À1 highly collimated, massive (0.03 M ) bipolar outflow with a very large scalar momentum (about 10 gcms ), and the characteristic spatiokinematic structure of bow shocks at the tips of this outflow. The H line shows an absorption feature blueshifted from the systemic velocity by 100 km sÀ1, which most likely arises in neutral interface material between the fast outflow and the dense walls of the bipolar lobes at low latitudes. The fast outflow in I22036, as in most PPNs, cannot be driven by radiation pressure. We find an unresolved source of submillimeter (and millimeter- wave) continuum emission in I22036, implying a very substantial mass (0.02Y0.04 M ) of large (radius k1 mm), cold (P50 K) dust grains associated with I22036’s toroidal waist. -

1999-2000 Annual Report

Anglo-Australian Observatory Annual Report of the Anglo-Australian Telescope Board 1 July 1999 to 30 June 2000 ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN OBSERVATORY PO Box 296, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 167 Vimiera Road, Eastwood, NSW 2122, Australia PH (02) 9372 4800 (international) + 61 2 9372 4800 FAX (02) 9372 4880 (international) + 61 2 9372 4880 e-mail [email protected] ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN TELESCOPE BOARD PO Box 296, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 167 Vimiera Road, Eastwood, NSW 2122, Australia PH (02) 9372 4813 (international) + 61 2 9372 4813 FAX (02) 9372 4880 (international) + 61 2 9372 4880 e-mail [email protected] ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN TELESCOPE/UK SCHMIDT TELESCOPE PriVate Bag, Coonabarabran, NSW 2357, Australia PH (02) 6842 6291 (international) + 61 2 6842 6291 AAT FAX (02) 6884 2298 (international) + 61 2 6884 298 UKST FAX (02) 6842 2288 (international) + 61 2 6842 2288 WWW http://www.aao.gov.au/ © Anglo-Australian Telescope Board 2000 ISSN 1443-8550 COVER: A digital image of the Antennae galaxies (NGC4038-39) made by combining three images from the Tek2 CCD on the AAT (Steve Lee and David Malin). A new wide field CCD Imager (WFI) will come into use in 2000 and will enable many more images like this to be made. COVER DESIGN: Encore International COMPUTER TYPESET AT THE: Anglo-Australian ObserVatory ii The Right Honourable Stephen Byers, MP, President of the Board of Trade and Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland The Honourable Dr David Kemp, MP, Minister for Education, Training and Youth Affairs GoVernment of the Commonwealth of Australia In accordance with Article 8 of the Agreement between the Australian GoVernment and the GoVernment of the United Kingdom to proVide for the establishment and operation of an optical telescope at Siding Spring Mountain in the state of New South Wales, I present herewith a report by the Anglo-Australian Telescope Board for the year from 1 July 1999 to 30 June 2000. -

Planetary Nebulas

The History, Observation, and Science of Planetary Nebulas Plus: Mars Exploration Update (at end) Tuesday, February 5, 2013 What is a “Planetary” Nebula? Dark Nebula: We see it because of light it blocks. Emission Nebula: The cloud itself glows. Planetary Nebula Galaxies were once classed as nebulas, too. Supernova Remnant: Reflection Nebula: What’s left after a star goes “boom” Reflects light from a star. “nebula” is latin for mist, fog, or cloud. Tuesday, February 5, 2013 Origin of the Term ‘Planetary Nebula’ William Herschel: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1785, Volume 75, Page 263 ff*: Planetary Nebulae “I shall conclude this paper with an account of a few heavenly bodies, that from their singular appearance leave me almost in doubt where to class them...being all over of an uniform brightness, which it differs from nebulae, it light seems however to be of the starry nature, which suffers not so much as the planetary disks are know to do, when much magnified. The planetary appearance of the first two is so remarkable that we can hardly suppose them to be nebulae; their light is so uniform, as well as vivid, the diameters so small and well defined as to make it almost improbable that they should belong to that species of bodies. On the other hand, the effect of different power seems to be much against their light’s being of a planetary nature, since it preserves its brightness nearly in the same manner as to the stars in similar trials.” He describes five planetaries (Six listed, 5 and 6 appear to be repeats): NGC 7293 (Helix), NGC 7662 (Blue Snowball), NGC 6369 (Little Ghost), NGC 6853 (Dumbbell), NGC 6894 (Diamond Ring) He makes two guesses in 1785 about what they are: Star clusters that can’t be resolved, or Dead or dying stars, possibly multiple stars falling into each other. -

Abstracts of Talks 1

Abstracts of Talks 1 INVITED AND CONTRIBUTED TALKS (in order of presentation) Milky Way and Magellanic Cloud Surveys for Planetary Nebulae Quentin A. Parker, Macquarie University I will review current major progress in PN surveys in our own Galaxy and the Magellanic clouds whilst giving relevant historical context and background. The recent on-line availability of large-scale wide-field surveys of the Galaxy in several optical and near/mid-infrared passbands has provided unprecedented opportunities to refine selection techniques and eliminate contaminants. This has been coupled with surveys offering improved sensitivity and resolution, permitting more extreme ends of the PN luminosity function to be explored while probing hitherto underrepresented evolutionary states. Known PN in our Galaxy and LMC have been significantly increased over the last few years due primarily to the advent of narrow-band imaging in important nebula lines such as H-alpha, [OIII] and [SIII]. These PNe are generally of lower surface brightness, larger angular extent, in more obscured regions and in later stages of evolution than those in most previous surveys. A more representative PN population for in-depth study is now available, particularly in the LMC where the known distance adds considerable utility for derived PN parameters. Future prospects for Galactic and LMC PN research are briefly highlighted. Local Group Surveys for Planetary Nebulae Laura Magrini, INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri The Local Group (LG) represents the best environment to study in detail the PN population in a large number of morphological types of galaxies. The closeness of the LG galaxies allows us to investigate the faintest side of the PN luminosity function and to detect PNe also in the less luminous galaxies, the dwarf galaxies, where a small number of them is expected. -

![Arxiv:1101.2214V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 11 Jan 2011](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7461/arxiv-1101-2214v1-astro-ph-ga-11-jan-2011-1737461.webp)

Arxiv:1101.2214V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 11 Jan 2011

YOUNG PLANETARY NEBULAE: HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE IMAGING AND A NEW MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM Raghvendra Sahai1, Mark Morris2, Gregory Villar3 Received ; accepted arXiv:1101.2214v1 [astro-ph.GA] 11 Jan 2011 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, MS 183-900, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 2Division of Astronomy, Department of Physics and Astrophysics, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095 3Cal Poly, Pomona –2– ABSTRACT Using Hubble Space Telescope images of 119 young planetary nebulae, most of which have not previously been published, we have devised a comprehensive morphological classification system for these objects. This system generalizes a recently devised system for pre-planetary nebulae, which are the immediate progenitors of planetary nebulae (PNs). Unlike previous classification studies, we have focussed primarily on young PNs rather than all PNs, because the former best show the influences or symmetries imposed on them by the dom- inant physical processes operating at the first and primary stage of the shaping process. Older PNs develop instabilities, interact with the ambient interstellar medium, and are subject to the passage of photoionization fronts, all of which obscure the underlying symmetries and geometries imposed early on. Our classi- fication system is designed to suffer minimal prejudice regarding the underlying physical causes of the different shapes and structures seen in our PN sample, however, in many cases, physical causes are readily suggested by the geometry, along with the kinematics that have been measured in some systems. Secondary characteristics in our system such as ansae indicate the impact of a jet upon a slower-moving, prior wind; a waist is the signature of a strong equatorial con- centration of matter, whether it be outflowing or in a bound Keplerian disk, and point symmetry indicates a secular trend, presumably precession, in the ori- entation of the central driver of a rapid, collimated outflow. -

Popular Names of Deep Sky (Galaxies,Nebulae and Clusters) Viciana’S List

POPULAR NAMES OF DEEP SKY (GALAXIES,NEBULAE AND CLUSTERS) VICIANA’S LIST 2ª version August 2014 There isn’t any astronomical guide or star chart without a list of popular names of deep sky objects. Given the huge amount of celestial bodies labeled only with a number, the popular names given to them serve as a friendly anchor in a broad and complicated science such as Astronomy The origin of these names is varied. Some of them come from mythology (Pleiades); others from their discoverer; some describe their shape or singularities; (for instance, a rotten egg, because of its odor); and others belong to a constellation (Great Orion Nebula); etc. The real popular names of celestial bodies are those that for some special characteristic, have been inspired by the imagination of astronomers and amateurs. The most complete list is proposed by SEDS (Students for the Exploration and Development of Space). Other sources that have been used to produce this illustrated dictionary are AstroSurf, Wikipedia, Astronomy Picture of the Day, Skymap computer program, Cartes du ciel and a large bibliography of THE NAMES OF THE UNIVERSE. If you know other name of popular deep sky objects and you think it is important to include them in the popular names’ list, please send it to [email protected] with at least three references from different websites. If you have a good photo of some of the deep sky objects, please send it with standard technical specifications and an optional comment. It will be published in the names of the Universe blog. It could also be included in the ILLUSTRATED DICTIONARY OF POPULAR NAMES OF DEEP SKY. -

A Study of Planetary Nebulae Using the Faint Object Infrared Camera for the SOFIA Telescope

A Study of Planetary Nebulae Using the Faint Object Infrared Camera for the SOFIA Telescope Jessica Davis, Michael Werner (Mentor), Raghvendra Sahai (Co-Mentor) A planetary nebula is formed following an intermediate-mass (1-8 M ) star’s evolution off of the main sequence; it undergoes a phase of mass loss whereby the stellar envelope is ejected and the core is converted into a white dwarf. Planetary nebulae often display complex morphologies such as waists or torii, rings, collimated jet-like outflows, and bipolar symmetry, but exactly how these features form is unclear. To study how the distribution of dust in the interstellar medium affects their morphology, we utilize the Faint Object InfraRed CAmera for the SOFIA Telescope (FORCAST) to obtain well-resolved images of four planetary nebulae—NGC 7027, NGC 6543, M2-9, and the Frosty Leo Nebula—at wavelengths where they radiate most of their energy. We retrieve mid infrared images at wavelengths ranging from 6.3 to 37.1 um for each of our targets. IDL (Interactive Data Language) is used to perform basic analysis. We select M2-9 to investigate further; analyzing cross sections of the southern lobe reveals a slight limb brightening effect. Modeling the dust distribution within the lobes reveals that the thickness of the lobe walls is higher than anticipated, or rather than surrounding a vacuum surrounds a low density region of tenuous dust. Further analysis of this and other planetary nebulae is needed before drawing more specific conclusions. As the collapsing core of the post-MS star sloughs off its envelope Our goal is not only to determine how the dust distribution in in layers, these layers interact with both each other (e.g. -

Asymmetrical Planetary Nebulae Ii: from Origins to Microstructures

ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF THE PACIFIC CONFERENCE SERIES Volume 199 ASYMMETRICAL PLANETARY NEBULAE II: FROM ORIGINS TO MICROSTRUCTURES Proceedings of a conference held at Massachusetts Institute of Technology at Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA 3-6 August 1999 Edited by Joel H. Kastner Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, New York, USA Noam Soker Department of Physics, University of Haifa - Oranim, Tivon, Israel and Saul A. Rappaport Physics Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. in Contents DEDICATION CONFERENCE PHOTO PREFACE LIST OF PARTICIPANTS I. OVERVIEW OF KEY THEORY AND OBSERVATIONS From Historical Perspectives to Some Modern Possibilities I.E. Aller A Retrospective: Interacting Winds Theory, Two Decades Later 5. Kwok The Morphological and Structural Classification of Planetary Nebulae A. Manchado et al. Morphology vs. Physical Properties: Some Comments and Questions R.L.M. Corradi Planetary Nebulae with the Hubble Space Telescope Y. Terzian & A.R. Hajian Bipolar Planetary Nebulae: the Betes-Noires of Hydro Models B. Balick II. MASS LOSS AND STELLAR EVOLUTION: SETTING THE STAGE FOR ASYMMETRICAL PLANETARY NEBULAE Properties of AGB Star Progenitors P.R. Wood On the Transition from AGB Stars to Planetaries: The Spherical Case D. Schonberner & M. Steffen Asymmetric Outflows in Miras M. Karovska, K. Wood, & W. Hack The Transition to Axisymmetrical Mass Loss N. Soker VLBA Detection of Bipolar OH 1612 MHz Maser Emission Toward OH 37.1-0.8 Y. Gomez & L.F. Rodriguez Vlll Is the Outflow from RT Vir Bipolar or Rotating? J.A. Yates et al. 79 Accretion Disks around Late AGB Stars: Restrict ions and Characteristics M. -

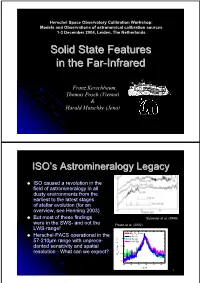

Solid State Features in the Far-Infrared

Herschel Space Observatory Calibration Workshop: Models and Observations of astronomical calibration sources 1-3 December 2004, Leiden, The Netherlands SolidSolid StateState FeaturesFeatures inin thethe FarFar--InfraredInfrared Franz Kerschbaum, Thomas Posch (Vienna) & Harald Mutschke (Jena) ISOISO’’ss AstromineralogyAstromineralogy LegacyLegacy z ISO caused a revolution in the field of astromineralogy in all dusty environments from the earliest to the latest stages of stellar evolution (for an overview, see Henning 2003) z But most of these findings Sylvester et al. (1999) were in the SWS- and not the Posch et al. (2002) LWS-range! LWS-range! 1.1 Mg Fe O em. 0.1 0.9 z Herschel-PACS operational in the g Her (1) 2 λ 1.0 g Her (2) * 57-210µm range with unprece- ν V1943 Sgr dented sensitivity and spatial 0.9 resp. F resolution - What can we expect? abs 0.8 Q 0.7 14 16 18 20 22 24 λ (µm) 2 SomeSome basicbasic physicsphysics Principal mechanisms for emission in the 57µm+ range: 1. Lattice vibrations of heavy ions and/or ion groups with low bond energies z Example KBr is highly transparent in the NIR and MIR (matrix material for transmission spectroscopy!) but opaque in the FIR (transverse optical mode at 86µm). NaCl and KCl are similar cases (61 and 69µm, respectively) z This can be understood by a harm. oscillator law (e.g. Beran et al. 2004): µ λ ∝ vib k with µ being the reduced mass and k the force constant. z Limited range of mass numbers of dust forming elements 3 SomeSome basicbasic physicsphysics Principal mechanisms for emission in the 57µm+ range: 2.