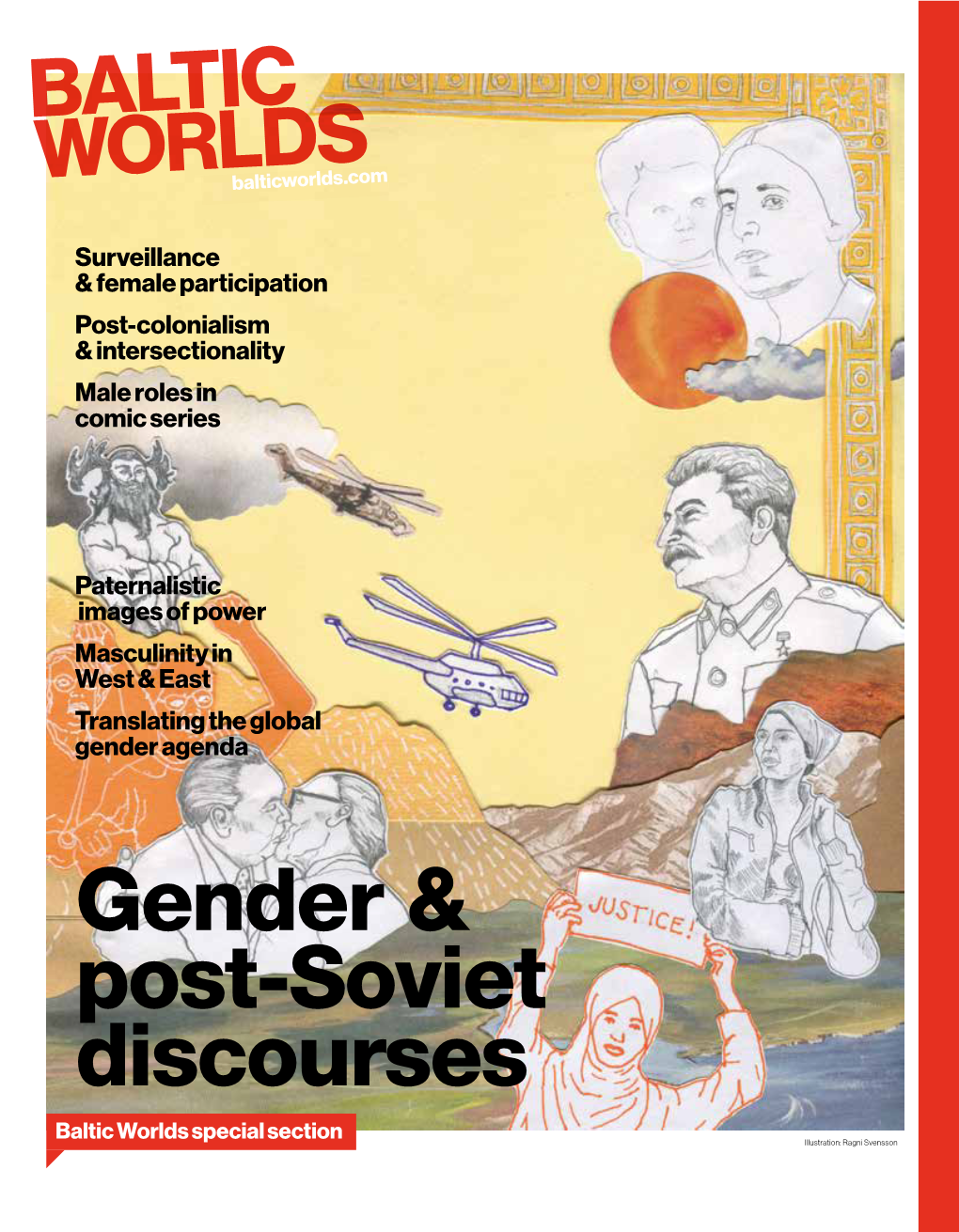

Gender & Post-Soviet Discourses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raisa Gorbacheva, the Soviet Union’S Only First Lady

Outraging the People by Stepping out of the Shadows Gender roles, the ‘feminine ideal’ and gender discourse in the Soviet Union and Raisa Gorbacheva, the Soviet Union’s only First Lady. Noraly Terbijhe Master Thesis MA Russian & Eurasian Studies Leiden University January 2020, Leiden Everywhere in the civilised world, the position, the rights and obligations of a wife of the head of state are more or less determined. For instance, I found out that the President’s wife in the White House has special staff to assist her in preforming her duties. She even has her own ‘territory’ and office in one wing of the White House. As it turns out, I as the First Lady had only one tradition to be proud of, the lack of any right to an official public existence.1 Raisa Maximovna Gorbacheva (1991) 1 Translated into English from Russian. From: Raisa Gorbacheva, Ya Nadeyus’ (Moscow 1991) 162. 1 Table of contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Literature review ........................................................................................................................... 9 3. Gender roles and discourse in Russia and the USSR ................................................................. 17 The supportive comrade ................................................................................................................. 19 The hardworking mother ............................................................................................................... -

Please Download Issue 1-2 2015 Here

B A L A scholarly journal and news magazine. April 2015. Vol. VIII:1–2. From TIC the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. The story of Papusza, W a Polish Roma poet O RLDS A pril 2015. V ol. VIII BALTIC :1–2 WORLDSbalticworlds.com Special section Gender & post-Soviet discourses Special theme Voices on solidarity S pecial section: pecial Post- S oviet gender discourses. gender oviet Lost ideals, S pecial theme: pecial shaken V oices on solidarity solidarity on oices ground also in this issue Illustration: Karin Sunvisson RUS & MAGYARS / EsTONIA IN EXILE / DIPLOMACY DURING WWII / ANNA WALENTYNOWICZ / HIJAB FASHION Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies WORLDSbalticworlds.com in this issue editorial Times of disorientation he prefix “post-” in “post-Soviet” write in their introduction that “gender appears or “post-socialist Europe” indicates as a conjunction between the past and the pres- that there is a past from which one ent, where the established present seems not to seeks to depart. In this issue we will recognize the past, but at the same time eagerly Tdiscuss the more existential meaning of this re-enacts the past discourses of domination.” “departing”. What does it means to have all Another collection of shorter essays is con- that is rote, role, and rules — and seemingly nected to the concept of solidarity. Ludger self-evident — rejected and cast away? What Hagedorn has gathered together different Papusza. is it to lose the basis of your identity when the voices, all adding insights into the meaning of society of which you once were a part ceases solidarity. -

April 2016 • ISSN 1801-3422

POLITICS IN CENTRAL EUROPE The Journal of the Central European Political Science Association Volume 12 • Number 1 • April 2016 • ISSN 1801-3422 ESSAYS Volume 12 • Number 1 • April 2016 1 • April 12 • Number Volume Russian Exceptionalism: A Comparative Perspective Brendan Humphreys State Civilisation: The Statist Core of Vladimir Putin’s Civilisational Discourse and its Implications for Russian Foreign Policy Fabian Linde Latin American Vector in Russian’s Foreign Policy: POLITICS IN CENTRAL IN POLITICS EUROPE Identities and Interests in the Russian-Venezuela Partnership Alexandra Sitenko Afghanistan’s Signifi cance for Russia in the 21st Century: Interests, Perceptions and Perspectives Kaneshko Sangar Russia’s Backyard – Unresolved Confl icts in the Caucasus Dominik Sonnleitner POLITICS in Central Europe The Journal of the Central European Political Science Association Volume 12 Number 1 April 2016 ISSN 1801-3422 EDITORIAL ESSAYS Russian Exceptionalism: A Comparative Perspective Brendan Humphreys State Civilisation: The Statist Core of Vladimir Putin’s Civilisational Discourse and its Implications for Russian Foreign Policy Fabian Linde Latin American Vector in Russian’s Foreign Policy: Identities and Interests in the Russian ‑Venezuela Partnership Alexandra Sitenko Afghanistan’s Significance for Russia in the 21st Century: Interests, Perceptions and Perspectives Kaneshko Sangar Russia’s Backyard – Unresolved Conflicts in the Caucasus Dominik Sonnleitner The Construction of Crisis: The ‘internal ‑identitarian’ Nexus in Russian ‑European Relations and its Significance beyond the Ukraine Crisis Moritz Pieper Sanctions in Russian Political Narrative Magda B. Leichtova Narratives of Russia’s ‘Information Wars’ Ekaterina Kalinina The Power of the Capability Constraint: On Russia’s Strength in the Arctic Territorial DIspute Irina Valkova Politics in Central Europe – The Journal of Central European Political Science Association is the official Journal of the Central European Political Science Association (CEPSA). -

Relating to the Real

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2016. Vol. IX:4. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. New excerpt by award-winning Lithuanian writer December 2016. Vol. IX:4 BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com Relating to the real Special section: Perspectives and narratives on socialist realism Adorno’s concept of realism Nabokov and cinematic realism Gaidar and the fostering of socialists The truth and the real Special section: Special Translations of reality in Soviet literature Lapin on history writing Swedish painters’ interpretations of realism Perspectives and narratives on socialist realism. socialist on narratives and Perspectives also in this issue Illustration: Karin Sunvisson WAR ON DRUGS IN RUSSIA / FEMINISM ON NEOLIBERALISM / ANTI-SEMITISM IN POLAND / EXILE COMMUNITIES Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies contents 3 colophon WORLDSbalticworlds.com Baltic Worlds is published by the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) at Södertörn University, Sweden. editorial in this issue Editor-in-chief Ninna Mörner Publisher Joakim Ekman Social reality & socialist realism Scholarly advisory council Thomas Andrén, Södertörn hen in daily life we speak of appear differently from another University; Sari Autio-Sarasmo, “reality”, we often use the word angle. In this issue we devote a Aleksanteri Institute, Helsinki; to refer to harsh circumstances substantial section to the dogmas Sofie Bedford, UCRS, Uppsala and the darker side of society. It and ambiguities of the real, and interview reviews University; Michael Gentile, Wseems to be something raw and confined to hid- our guest editor Tora Lane has Helsinki University; Markus Huss, 4 Lithuanian writer. -

Session 1 – Saturday – 12:00-1:45 Pm

8:00 – 11:40 am East Coast Consortium of Slavic Library Collections - (Meeting) - Foothill I, 2 Midwest Slavic and Eurasian Library Consortium - (Meeting) - Pacific G, 4 Pacific Coast Slavic and East European Library Consortium - (Meeting) - Foothill A, 2 8:00am – 12:00 pm ASEEES Board of Directors Meeting - (Meeting) - Pacific I, 4 8:30 – 11:40 am ASEEES Slavic Digital Humanities - Preconference Workshop - Foothill G1 & G2 (Breakout room), 2 9:30 – 11:30 am Central Asian, Russian and East European Writing Workshop - Pacific C, 4 Chair: Elizabeth Walker, Taylor & Francis Part.: Luca Anceschi, U of Glasgow (UK) Matthew Rendle, U of Exeter (UK) Session 1 – Saturday – 12:00-1:45 pm Association for Women in Slavic Studies - (Meeting) - Sierra F, 5 1-01 Authoritarian Politics in Russia: Regulation, Popular Approval, and Social Policy - Foothill A, 2 Chair: Margaret Hanson, Ohio State U Papers: Dinissa Duvanova, Lehigh U "Post-communist Regulatory State" Noah Buckley, Columbia U / NRU Higher School of Economics (Russia) "Why So Insecure? Popular Approval of Authoritarian Government" Amanda Leigh Zadorian, NRU Higher School of Economics (Russia) "How ‘Rentier' was Russian Social Policy During the Commodity Price Boom?" Disc.: Margaret Hanson, Ohio State U 1-02 Collaboration and Tensions Across Opposite Systems of Belief. Communist Romania's Cultural Relations and Ideological Contention with the West - Foothill B, 2 Chair: Corina Dobos, U of Bucharest (Romania) Papers: Irina Nastasa-Matei, U of Bucharest (Romania) "Academic Exchange Across the -

Art & Aesthetics

A scholarly journal and news magazine. October 2017. Vol. X:3. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. 13 pages of reviews BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com The Russian Revolution reshaped everything: Art & Aesthetics • Art education in transformation • Global ambitions captured in one day • Building for men of the future • The legacy in literature – the void also in this issue Illustration: Karin Sunvisson ANTI-GENDERISM / MEMORY & MONUMENTS / OPEN SOCIETY ARCHIVES / KGB IN RIGA / THE NOBEL FAMILY Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies contents 3 colophon WORLDSbalticworlds.com Baltic Worlds is published by the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) at Södertörn University, Sweden. Editor-in-chief editorial in this issue Ninna Mörner Publisher Joakim Ekman Scholarly advisory council Revolutionary principles Thomas Andrén, Södertörn University; Sari Autio-Sarasmo, n October 2017, one hundred years since In this issue, however, we Aleksanteri Institute, Helsinki; the revolutionary era in Russia, we devote also dig into the past. In a feature theme Sofie Bedford, UCRS, Uppsala a special section to touch on certain as- article, Anna Kharkina presents feature University; Michael Gentile, 4 Open Society Archives. Playing an pects of the impact this disruptive event insights into how the Open Society Helsinki University; Markus Huss activist role, Anna Kharkina Influences of the Ihad on art, film, literature and aesthetics. Archive (OSA) has struggled over -

Survival Kit in Riga Maria Janion a Great European Intellectual

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2011. Vol IV:4 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) commentaries: Södertörn University, Stockholm Poland and Russia Survival Kit in Riga BALTIC Women’s Solidarity W O Rbalticworlds.com L D S Maria Janion A great European The dividing intellectual Christmas tree also in this issue ILLUSTRATION: RAGNI SVENSSON RUSSIAN INFRASTRUCTURE / YUGOSLAVIAN WAR MONUMENTS / WITTE / NEW SPATIAL HISTORY / MOSCOW FASHION global2 week editors’ column BALTIC editorial 3 Culture in More diatribe than dialogue when old top dogs deliberate the periphery W O R L Dbalticworlds.com S “Dialogue”, said Gen- thing we have not done!” Ekaterina Kalinina finds revanchism, Age of unexpected nady Burbulis, first The Russians had already or a certain measure of megalomania, Sponsored by the Foundation deputy to the chairman lost all their savings by to be the reason that two indepen- for Baltic and East European Studies of the government under 1990. “They had nothing dent fashion weeks have been held in revolts Boris Yeltsin, at a top- left to lose”, he said. “It St. Petersburg in the last two years. a quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2011. vol iv:4 from the centre for Baltic and east european studies (cBees) commentaries: level seminar with former was all fictitious money.” Despite several similar events held in södertörn university, stockholm poland and russia Survival kit i n R i g a BALTIC Wom e n’s heads of state in Soviet- And the former engine Moscow as well, the fashion industry S ol i d a r it y contents orld War I saw the nomic-structural thinking and action at WORLDS D L R O W balticworlds.com Maria Janion A great European ruled Europe convened of growth, the military- is not an up-and-coming business in The dividing intellectual dissolution of three the Union level. -

Mediated Post-Soviet Nostalgia

MEDIATED POST-SOVIET NOSTALGIA Ekaterina Kalinina MEDIATED POST-SOVIET NOSTALGIA Ekaterina Kalinina Södertörns högskola © Ekaterina Kalinina 2014 Södertörn University SE-141 89 Huddinge Cover Image: Olcay Yalçın Cover and content layout: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2014 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 98 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-87843-08-2 ISBN 978-91-87843-09-9 (digital) Abstract Post-Soviet nostalgia, generally understood as a sentimental longing for the Soviet past, has penetrated deep into many branches of Russian popular culture in the post-1989 period. The present study investigates how the Soviet past has been mediated in the period between 1991 and 2012 as one element of a prominent structure of feeling in present-day Russian culture. The Soviet past is represented through different mediating arenas – cultural domains and communicative platforms in which meanings are created and circulated. The mediating arenas examined in this study include television, the Internet, fashion, restaurants, museums and the- atre. The study of these arenas has identified common ingredients which are elements of a structure of feeling of the period in question. At the same time, the research shows that the representations of the past vary with the nature of the medium and the genre. The analysis of mediations of the Soviet past in Russian contemporary culture reveals that there has been a change in the representations of the Soviet past during the past twenty years, which roughly correspond to the two decades marked by the presidencies of Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s and of Vladimir Putin in the 2000s (including Dmitrii Medvedev’s term, 2008–2012). -

Gendering in Political Journalism

Gendering in Political Journalism To my family Örebro Studies in Media and Communication 18 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 97 LIUDMILA VORONOVA Gendering in Political Journalism A Comparative Study of Russia and Sweden © Liudmila Voronova, 2014 Title: Gendering in Political Journalism. A Comparative Study of Russia and Sweden Publisher: Örebro University 2014 www.oru.se/publikationer-avhandlingar Print: INEKO, Kållered 09/2014 ISSN 1651-4785 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-7529-033-1 Abstract Liudmila Voronova (2014): Gendering in Political Journalism. A Comparative Study of Russia and Sweden. Örebro Studies in Media and Communication 18, Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 97, 277 pp. The news media are expected to provide equal space to female and male po- litical actors, promoting the idea of equal access to political power, since they are recognized as a holder of power with a social responsibility to respect gender equality. However, as previous research shows, political news cover- age is characterized by so-called “gendered mediation” (Gidengil and Everitt 1999), i.e., gender imbalance, stereotypes, and a lack of discussions about gender inequality. Scholars point to media logic, organization, and individual characteristics of journalists as the main reasons for this pattern, but still very little is known about how and why gendered mediation is practiced and pro- cessed in political news. This dissertation focuses on gendering understood as the perceived im- print of gender on the media portrayal of politics and politicians, as well as the processes by which gendered representations materialize. By applying a perspective of comparative journalism culture studies (Hanitzsch 2007; Hanitzsch and Donsbach 2012), it examines the processes and modes of origin of gendering as they are perceived and experienced by journalists. -

Liebig2020.Pdf (3.184Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Nostalgia Re-Written. Boris Akunin’s Fandorin Project and the Detective (Re-)Discovery of Empire Anne Liebig Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) The University of Edinburgh 2020 Contents List of Illustrations ..................................................................................................... 3 Note on Transliteration ............................................................................................. 4 Abstract of Thesis ....................................................................................................... 5 Lay Summary of Thesis ............................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

Please Download Issue 1-2, 2021 Here

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. April 2021. Vol. XIV:1–2. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. Review: Jan Grabowski’s new book in Polish April 2021. Vol. XIV:1–2 BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com Kazakh dance and emancipation during Stalinism Sami village victory over the Swedish state Patriotic education of youth in modern Russia Depictions of Siberian peoples in the 18th century Traditional life vs nation building nation vs life Traditional Traditional life vs nation building also in this issue Z Sunvisson Karin Illustration: THE LEGACY OF 1989 / LGBTQ+ IN BELARUS / LUTHERAN ST. PETERSBURG / THE THREE SEAS INITIATIVE Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies WORLDSbalticworlds.com editorial in this issue Nation building seen from the periphery he Bergholtz collection with over 200 during Stalinism on the fringes of hand painted images of the peoples the Soviet Union, and also its con- of the Russian Empire, dating from sequences for Shara Zhienkulova the first half of the 18th century, has as an individual and an artist bal- Thitherto been largely unknown. In their essay ancing her own ambitions, her love Nathaniel Knight and Edward Kasinec describe for the Kazakh culture and the dan- the contents of the collection, particularly with gerous but prosperous situation regard to its depictions of Siberian peoples and of being a role model for Kazakh Ukrainians. Images portraying life in the distant women in Stalin’s brutal modern- Russian and nearly unexplored peripheries of the Em- ization reform programs. pire were unusual at this time.