Kolkhozes, Sovkhozes, and Shirkats of Yangibazar (1960-2002)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Water Use and Crop Allocation for the Khorezm Region in Uzbekistan Using an Integrated Hydrologic -Economic Model

-Zentrum für Entwicklungsforschung- Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn ANALYSIS OF WATER USE AND CROP ALLOCATION FOR THE KHOREZM REGION IN UZBEKISTAN USING AN INTEGRATED HYDROLOGIC -ECONOMIC MODEL Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften (Dr. Agr.) der Hohen Landwirtschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt am 19.11.2010 von Tina-Maria Schieder aus Bonn (Deutschland) Referent: PD Dr. P. Wehrheim Korreferent: Prof. Dr. B. Diekkrüger Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 16.03.2011 Erscheinungsjahr: 2011 Diese Dissertation wird auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni.bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert. D98 Abstract Sustainable and efficient water management is of central importance for the dominant agricultural sector and thus for the population and the environment of the Khorezm region. Khorezm is situated in the lower Amu Darya river basin in the Central Asian Republic of Uzbekistan and the delta region of the Aral Sea. Recently, Khorezm has experienced an increase in ecological, economic and social problems. The deterioration of the ecology is a result of the vast expansion of the agricultural area (which began in the Soviet period in Uzbekistan), the utilization of marginal land and a very intensive production of cotton on a significant share of arable land. Supplying food for an increasing population and overcoming with the arid climate in Khorezm require intensive irrigation. However, the water distribution system is outdated. Current irrigation strategies are not flexible enough to cope with water supply and crop water demand, as both are becoming more variable. The political system, with its stringent crop quotas for cotton and wheat, nepotism, missing property rights and lack of incentives to save water, has promoted unsustainable water use rather than preventing it. -

World Bank Document

Ministry of Agriculture and Uzbekistan Agroindustry and Food Security Agency (UZAIFSA) Public Disclosure Authorized Uzbekistan Agriculture Modernization Project Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Tashkent, Uzbekistan December, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan CC Civil Code DCM Decree of the Cabinet of Ministries DDR Diligence Report DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DSEI Draft Statement of the Environmental Impact EHS Environment, Health and Safety General Guidelines EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ES Environmental Specialist ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FS Feasibility Study GoU Government of Uzbekistan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism H&S Health and Safety HH Household ICWC Integrated Commission for Water Coordination IFIs International Financial Institutions IP Indigenous People IR Involuntary Resettlement LAR Land Acquisition and Resettlement LC Land Code MCA Makhalla Citizen’s Assembly MoEI Ministry of Economy and Industry MoH Ministry of Health NGO Non-governmental organization OHS Occupational and Health and Safety ОP Operational Policy PAP Project Affected Persons PCB Polychlorinated Biphenyl PCR Physical Cultural Resources PIU Project Implementation Unit POM Project Operational Manual PPE Personal Protective Equipment QE Qishloq Engineer -

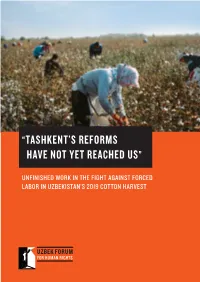

“Tashkent's Reforms Have Not

“TASHKENT’S REFORMS HAVE NOT YET REACHED US” UNFINISHED WORK IN THE FIGHT AGAINST FORCED LABOR IN UZBEKISTAN’S 2019 COTTON HARVEST “TASHKENT’S REFORMS HAVE NOT YET REACHED US” UNFINISHED WORK IN THE FIGHT AGAINST FORCED LABOR IN UZBEKISTAN’S 2019 COTTON HARVEST 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 KEY FINDINGS FROM THE 2019 HARVEST 6 METHODOLOGY 8 TABLE 1: PARTICIPATION IN THE COTTON HARVEST 10 POSITIVE TRENDS 12 FORCED LABOR LINKED TO GOVERNMENT POLICIES AND CONTROL 13 MAIN RECRUITMENT CHANNELS FOR COTTON PICKERS: 15 TABLE 2: PERCEPTION OF PENALTY FOR REFUSING TO PICK COTTON ACCORDING TO WHO RECRUITED RESPONDENTS 16 TABLE 3: WORKING CONDITIONS FOR PICKERS ACCORDING TO HOW THEY WERE RECRUITED TO PICK COTTON 16 TABLE 4: PERCEPTION OF COERCION BY RECRUITMENT METHODS 17 LACK OF FAIR AND EFFECTIVE RECRUITMENT SYSTEMS AND STRUCTURAL LABOR SHORTAGES 18 STRUCTURAL LABOR SHORTAGES 18 LACK OF FAIR AND EFFECTIVE RECRUITMENT SYSTEMS 18 FORCED LABOR MOBILIZATION 21 1. ABILITY TO REFUSE TO PICK COTTON 21 TABLE 5: ABILITY TO REFUSE TO PICK COTTON 21 TABLE 6: RESPONDENTS’ ABILITY TO REFUSE TO PICK COTTON ACCORDING TO HOW THEY WERE RECRUITED 22 2. MENACE OF PENALTY 22 TABLE 7: PENALTIES FOR REFUSAL 22 TABLE 8: PERCEIVED PENALTIES FOR REFUSAL TO PICK COTTON BY PROFESSION 23 3. REPLACEMENT FEES/EXTORTION 23 TABLE 9: FEES TO AVOID COTTON PICKING 23 CHART 1: PAYMENT OF FEES BY REGION 24 OFFICIALS FORCIBLY MOBILIZED LABOR FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE HARVEST TO MEET LABOR SHORTAGES 24 LAW ENFORCEMENT, MILITARY, AND EMERGENCIES PERSONNEL 24 PUBLIC UTILITIES -

List of Districts of Uzbekistan

Karakalpakstan SNo District name District capital 1 Amudaryo District Mang'it 2 Beruniy District Beruniy 3 Chimboy District Chimboy 4 Ellikqala District Bo'ston 5 Kegeyli District* Kegeyli 6 Mo'ynoq District Mo'ynoq 7 Nukus District Oqmang'it 8 Qonliko'l District Qanliko'l 9 Qo'ng'irot District Qo'ng'irot 10 Qorao'zak District Qorao'zak 11 Shumanay District Shumanay 12 Taxtako'pir District Taxtako'pir 13 To'rtko'l District To'rtko'l 14 Xo'jayli District Xo'jayli Xorazm SNo District name District capital 1 Bog'ot District Bog'ot 2 Gurlen District Gurlen 3 Xonqa District Xonqa 4 Xazorasp District Xazorasp 5 Khiva District Khiva 6 Qo'shko'pir District Qo'shko'pir 7 Shovot District Shovot 8 Urganch District Qorovul 9 Yangiariq District Yangiariq 10 Yangibozor District Yangibozor Navoiy SNo District name District capital 1 Kanimekh District Kanimekh 2 Karmana District Navoiy 3 Kyzyltepa District Kyzyltepa 4 Khatyrchi District Yangirabad 5 Navbakhor District Beshrabot 6 Nurata District Nurata 7 Tamdy District Tamdibulok 8 Uchkuduk District Uchkuduk Bukhara SNo District name District capital 1 Alat District Alat 2 Bukhara District Galaasiya 3 Gijduvan District Gijduvan 4 Jondor District Jondor 5 Kagan District Kagan 6 Karakul District Qorako'l 7 Karaulbazar District Karaulbazar 8 Peshku District Yangibazar 9 Romitan District Romitan 10 Shafirkan District Shafirkan 11 Vabkent District Vabkent Samarqand SNo District name District capital 1 Bulungur District Bulungur 2 Ishtikhon District Ishtikhon 3 Jomboy District Jomboy 4 Kattakurgan District -

50022-002: Affordable Rural Housing Program

Environmental Monitoring Report # Annual Safeguard Monitoring Report February 2019 UZB: Affordable Rural Housing Program Prepared by Rustam Saparov (Management and Monitoring Unit) for the Ministry of Economy and Industry (MOEI) and the Asian Development Bank. This Environment monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Annual Safeguard Monitoring Report ___________________________________________________________________________ For FI operations Project Number: 3535 January-December 2018 Uzbekistan: Affordable Rural Housing Program (Financed by Asian Development Bank) For: Ministry of Economy and Industry Endorsed by: Management and Monitoring Unit February, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ARHP - Affordable Rural Housing Program CCRA - Climate change risk assessment DLI - Disbursement Linked Indicator EA - Executing Agency EA - Executive Agency EIA - Environmental impact assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan ESMS - Environmental and Social Management System HQ - Head Quarter IA - Implementation Agency IB - Ipoteka Bank IEE - Initial Environmental Examination MMU - Management -

Biogas Production from Agricultural Waste in the Aral Sea Basin Development of Pilot Plants

Final Report: Biogas production from agricultural waste in the Aral Sea Basin Development of pilot plants Authors: Hans-Christian Angele, EBP Schweiz AG/AngeleConsult Werner Edelmann, arbi GmbH Bahtyior Eshanov, Economics Department, Westminster International University in Tashkent Olimjon Saidmamatov, Economics Department, Urgench State University C:\Users\hc.angele\OneDrive\Ablage HC\Uzbekistan\90_ENDPRODUKTE\20190920_REPIC_Biogas Aral Sea FinalReport.docx Date of the Report: 20 of September 2019 Contract Number: 2016.11 Institution: EBP Schweiz AG/arbi GmbH Country: Uzbekistan Prepared by: EBP Schweiz AG Zollikerstrasse 65 CH-8702 Zollikon T +41 44 395 11 11, F +41 44 395 12 34, [email protected], www.ebp.ch arbi GmbH Heimelistrasse 35, CH-6314 Unterägeri T +41 763 2121, [email protected], www.arbi.ch With the Support of: REPIC Platform c/o NET Nowak Energy & Technology AG Waldweg 8, CH-1717 St. Ursen Tel: +41(0)26 494 00 30, Fax: +41(0)26 494 00 34, [email protected] / www.repic.ch The REPIC Platform is a mandate issued by the: Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC Federal Office for the Environment FOEN Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE The author(s) are solely responsible for the content and conclusions of this report. 2/40 C:\Users\hc.angele\OneDrive\Ablage HC\Uzbekistan\90_ENDPRODUKTE\20190920_REPIC_Biogas Aral Sea FinalReport.docx Contents 1. Summary ...................................................................................................................................... -

Multi-Scale Targeting of Land Degradation in Northern Uzbekistan Using Satellite Remote Sensing

Multi-scale targeting of land degradation in northern Uzbekistan using satellite remote sensing Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorlegt von Olena Dubovyk aus Kyiv, Ukraine Bonn, July 2013 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch‐Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich‐Wilhelms‐Universität Bonn Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Gunter Menz Gutachter: Prof Dr. Christopher Conrad Tag der Promotion: 18.10.2013 Erscheinungsjahr: 2013 With patience, it is possible to dig a well with a teaspoon. Ukrainian proverb To see a friend no road is too long. Ukrainian proverb ABSRACT Advancing land degradation (LD) in the irrigated agro‐ecosystems of Uzbekistan hinders sustainable development of this predominantly agricultural country. Until now, only sparse and out‐of‐date information on current land conditions of the irrigated cropland has been available. An improved understanding of this phenomenon as well as operational tools for LD monitoring is therefore a pre‐requisite for multi‐scale targeting of land rehabilitation practices and sustainable land management. This research aimed to enhance spatial knowledge on the cropland degradation in the irrigated agro‐ecosystems in northern Uzbekistan to support policy interventions on land rehabilitation measures. At the regional level, the study combines linear trend analysis, spatial relational analysis, and logistic regression modeling to expose the LD trend and to analyze the causes. Time series of 250‐m Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), summed over the growing seasons of 2000‐2010, were used to determine areas with an apparent negative vegetation trend; this was interpreted as an indicator of LD. -

Full Text: DOI

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 12, No. 4, July-September, 2020. 1-8 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n4/v12n411.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n4.11 Sanctification of Water among the Population of the Khorezm Oasis Abidova Zaynab Kadirberganovna Head of the Department "Social sciences", Urgench Branch of the Tashkent Medical Academy Urgench, Khorezm, Uzbekistan. ORCID: 0000-0001-5440-4041. Email: [email protected] Abstract Water holds a specific place in life of the people of the Khorezm oasis located in the lower reaches of the deep Amu Darya River which are between the Kara-Kum and Kyzyl-Kum Deserts. This article is devoted to a study of natural places of a pilgrimage connected with the water cult elements of Khwarezm. The remnants of ancient religions are studied and analyzed and found that the rites that are connected with water are traced in the Khorezm oasis. Special attention is paid to the history of studying of genesis and evolution of a cult of water of the Khorezm hagiology and their roles in life of inhabitants of the Khorezm oasis. This can be an important step towards the of revival of spiritual and cultural life of the Uzbek people. Keywords: water, cult, places of a pilgrimage, legend, ceremony, Hubbi, Amu Darya. Introduction Khorezm, the most ancient cultural oasis located in lower reaches of the deep Amu Darya River and between the deserts in the north of Uzbekistan. Khorezm is considered as one of the centers of the most ancient civilization. -

Suyun Qorayev. Toponimika

S. QORAYEV TOPONIMIKA 0 ‘zbekiston Respublikasi Oliy va o‘rta maxsus ta’lim vazirligi Muvoflqlashtiruvchi Kengashi tomonidan nashrga tavsiya etilgan 0 ‘zbekiston faylasuflari milliy jamiyati nashriyoti Toshkent — 2006 www.ziyouz.com kutubxonasi S. Qorayevning «Toponimika» qo‘llanmasi toponimikaning ilmiy-nazariy asoslariga hamda 0 ‘zbekiston toponimiyasiga bag‘ishlangan va shubhasiz, ijtimoiy hamda gumanitar fanlaming eng dolzarb, bir-biriga tutashib ketgan muhim masalalari majmuidan bahs etadi. Soha bo'yicha ko‘p yillik ilmiy-tadqiqot t^jri- basiga ega bo‘!gan muallif toponimikaning asosiy qonuniyatlari va tadqiqot yo'nalishlari kabi muhim muammolariga o‘ta sinchkovlik bilan yondoshgan. Ko‘p qatlamli va nihoyatda boy daliliy materiallar to'plagan va ularni ma’lum bir qolipgasolib umumlashtirgan hamda o'quv qo'llanmasi shakliga keltirgan. Bu asar shubhasiz, 0 ‘rta Osiyo, xususan 0 ‘zbekistonda toponimika fanining rivojiga qo‘shi!gan arzugulik hissadir. Muallif haqida ikki og‘iz so‘z. Suyun Qorayev sinchkov, zaxmatkash va serqirra olim. Muallif yarim asrdan beri toponimika bilan shug‘tiHanib, bir necha lug‘at, monografiya va risola, ikki yuzdan ortiq ilmiy maqolalar chop etgan. Taniqli topaniniist olim T.Nafasov aytganidek, S.Qorayevnmg toponimik lug‘atlari, risolalari, maqolalari xalq mul- kiga aylangan. 0 ‘zbekistonda toponimika fani bo^yicha dastfabki o‘quv qoMlanmasjga respublikaning yetakchi toponimisti S.Qorayevning muallif bo'Irshi qonuniy bir holdir. Maxsus mitharrir, akademik A.R. Muhammadjonov. Qo‘Ffanmada toponimikaning umumiy qonuniyatlari bay on etilgan. Hududiy toponimlar, geografik nomlami hosil qiladigan so‘zIar izohlangan, amaliy topo nimika haqida tushuncha berilgan hamda ayrim yozma yodgorliklar toponimik jihatdan tahlil qilingan. O'qituvchilar, shuningdek, etfmologrya havaskcdari ushbu kitobdan tabay qiziqarli ma’lumotlar topa oladilar, degan umiddamiz. -

Entrepreneurship in Rural Areas of Khorezm Region and the Role of Entrepreneurship in Villages

Central Asian Problems of Modern Science and Education Volume 2020 Issue 1 Article 1 2-25-2020 ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN RURAL AREAS OF KHOREZM REGION AND THE ROLE OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN VILLAGES T.B. Umidjanovich PhD Student of Tourism and economy faculty of Urgench state university, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/capmse Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Umidjanovich, T.B. (2020) "ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN RURAL AREAS OF KHOREZM REGION AND THE ROLE OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN VILLAGES," Central Asian Problems of Modern Science and Education: Vol. 2020 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/capmse/vol2020/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Asian Problems of Modern Science and Education by an authorized editor of 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF MODERN SCIENCE, EDUCATION AND TRAINING. FEBRUARY, 2020-I. ISSN 2181-9750 UDK: 338.432.5 ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN RURAL AREAS OF KHOREZM REGION AND THE ROLE OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN VILLAGES Tadjiyev Bekzod Umidjanovich, PhD Student of Tourism and economy faculty of Urgench state university E-mail: [email protected] Annotation. This research paper discusses the specific characters of developing small business and entrepreneurship in rural regions and the role of farming, agriculture and agricultural organizations in producing agricultural product. Key words: small business and private entrepreneurship (SBPE), farming, agriculture, agricultural enterprise, enterprise in rural regions, enterprise. Аннотация. Ушбу мақолада кичик бизнес ва тадбиркорликни қишлоқ жойларида ривожлантириш хусусиятлари ва Хоразм вилоятида қишлоқ хўжалик маҳсулотларини етиштиришда фермер хўжаликлари, деҳқон хўжаликлари ва қишлоқ хўжалиги фаолиятини амалга оширувчи ташкилотларнинг ўрни ҳақида сўз юритилади. -

Actual Problems of Modern Science, Education and Training in the Region 2018-Iii

ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF MODERN SCIENCE, EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN THE REGION 2018-III 1 ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF MODERN SCIENCE, EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN THE REGION 2018-III CONTENTS ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF MATHEMATICS, PHYSICS AND MECANICS………………………………………………………………...5 Joao O.V., Khujatov N. J. MATHEMATICAL MODELLING OF BLOOD FLOW………………………………………………………………………….....5 MODERN PROBLEMS OF TECHNICAL SCIENCES………………15 Mardonov B. T. INVESTIGATION OF THE ACCURACY OF THE INSTALLATION OF CYLINDRICAL SPUR GEARS WHEN MACHINING WITH ROLLING TOOLS IN THE CONDITIONS OF NMP MU NMMC…………………………………………………………………………..15 Sarimksakov A. A., Rashidova S. Sh., Baltaeva M. M., Eshchanov Kh. O., Shigabutdinov A. A. STUDY OF COPPER-POLYMER COMPLEXES AND THEIR PRODUCTION………………………………………………………..22 ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF NATURAL SCIENCES…………………..26 Ruzmetov B., Rakhimova M., THE MAIN FACTORS OF ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE REGION………………….26 ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF MEDICINE………………………………..31 Nazarov K. D., Ganiev A. G., Urumbaeva S. A., Abdurashidov A.A., FEATURES OF FOOD MANIFESTATION ALLERGY IN CHILDREN WITH ATOPIC DERMATITIS………………………………………………………………….31 Nazarov K.D., Ganiev A.G., Efimenko O., Botirov A.R., IMMUNOLOGICAL MECHANISMS OF DEVELOPMENT OF COMPLICATED FORMS OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS……………………………………………………….39 Saduilayev O.K., THE STUDY OF THE INTESTINAL MICROBIOCENOSIS OF CHILDREN SUFFERING FROM COLIANT DISEASES WITH TRADITIONAL METHODS…………………………….44 ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY ………...48 Nurullaeva Sh. K., ETHNOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF MEN’S TRADITIONAL HATS OF KHOREZM OASIS……………………………..48 Sheripov U. A., IMPLEMENTATION ON METHODS OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCHES…………………………………………………………………53 Navruzov S. OREST SHKAPSKY’S OBSERVATIONS ON FIELD EXPERIMENTS IN THE AGRICULTURE OF KHIVA AT THE END OF 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURY…………………………………………..57 Rakhmanova Y. M., THE ART OF MUSIC AND DANCE IN KHIVA KHANATE……………………………………………………………………...64 Anyоzov R. -

Stakeholder Engagement Plan Horezm Oblast

APRIL 2019 REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN, HOREZM OBLAST SUE “DEPARTMENT OF OPERATION OF INTERREGIONAL WATER MAIN “TUYAMUYUN- URGENCH” EUROPEAN BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT HOREZM OBLAST WASTEWATER MODERNIZATION PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PLAN HOREZM OBLAST DRAFT ADDRESS CECT Consulting LLC 3-5, bld.1, Gazetniy Lane 125993 Moscow Russian Federation TEL +7 495 629 93 92 FAX +7 495 629 88 84 WWW cect.eu HOREZM OBLAST WASTEWATER MODERNIZATION PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PLAN HOREZM OBLAST DRAFT APRIL 2019 PROJECT NO. 161 DOCUMENT NO. Volume 3 VERSION 1 DATE OF ISSUE 1 April 2019 PREPARED AKAD CHECKED EVLA APPROVED SS HOREZM OBLAST WASTEWATER MODERNIZATION PROJECT - FEASIBILITY STUDY Stakeholder Engagement Plan 3 ABBREVIATIONS Company, State Unitary Enterprise “Department of Operation of Interregional Water Main Client, “Tuyamuyun-Urgench” (Horezm Oblast Water & Wastewater Company) Enterprise EBRD, Bank European Bank for Reconstruction and Development E&S Environmental and Social EHS Environment, Health and Safety ESAP Environmental and Social Action Plan LTIP Long-Term Investment Program NTS Non-Technical Summary O&M Operation and Maintenance OHS Occupational Health and Safety PIP Priority Investment Program PR EBRD Performance Requirements SEP Stakeholder Engagement Plan SPZ Sanitary-Protection Zone WS Water Supply WTP Water Treatment Plant WW Wastewater WWPS Wastewater Pumping Station WWTP Wastewater Treatment Plant HOREZM OBLAST WASTEWATER MODERNIZATION PROJECT - FEASIBILITY STUDY Stakeholder