Teachings of the Book of Mormon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relevance of Religious Freedom Michael K

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Vol. 2: Service & Integrity Life in the Law 12-15-2009 The Relevance of Religious Freedom Michael K. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/life_law_vol2 Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Young, Michael K., "The Relevance of Religious Freedom" (2009). Vol. 2: Service & Integrity. 16. https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/life_law_vol2/16 This Be Healers is brought to you for free and open access by the Life in the Law at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vol. 2: Service & Integrity by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Relevance of Religious Freedom Michael K. Young Tonight I will talk about some of the lessons I’ve learned about religious liberty as I’ve worked in academics and government—I want to discuss how those lessons can teach us what needs to be done, and how we as committed members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can fill those needs. I’ve spent 25 years as an academic studying Asian economic trends, political trends, and human rights, and I spent four years in government service in the George H. W. Bush administration. The timing in that administration gave me an opportunity to work closely on the issue of German unification as well as on some significant trade and human rights treaties. -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

THE BOOK of MORMON and the Descent Into Disse T the Book of by Daniel C

Come, Follow Me BOOK OF MORMON THE BOOK OF MORMON AND THE Descent into Disse t The Book of By Daniel C. Peterson n Professor of Islamic Studies and Arabic, Brigham Young University Mormon shows how dissension he Restoration began when the Father and the Son appeared to Joseph Smith, dispelling the “darkness and confusion” that had engulfed him during a and contention “division amongst the people,” a “war of words and tumult of opinions” start, as well as T(see Joseph Smith—History 1:5–20). how to create The revelation of the Book of Mormon followed. unity in Christ’s The Book of Mormon testifies “that Jesus is the Christ” (title page). But it also Church. offers case studies in how dissension arises and how it damages the Church and individuals. It was written “unto the confounding of false doctrines and laying down of contentions, and establishing peace” (2 Nephi 3:12). It doesn’t merely describe the foibles and foolishness of previous generations. It is for our day. We can, therefore, read it as a commentary on our time, a guide and a warning to us. In many ways, the Book of Mormon is a guidebook on how to unify God’s people in the faith, as well as how contention and dissension creep into the Church. Dissenters: Their Motives and Methods Nephite prophets repeatedly condemn contention, strife, and dissension.1 Satan, says Mormon, created contention to “harden the hearts of the people against that which was good and against that which should come” (Helaman 16:22). -

“And He Was Anti-Christ”: the Significance of the Eighteenth Year of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2 Daniel Belnap

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2019 “And he was Anti-Christ”: The Significance of the Eighteenth earY of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2 Daniel Belnap [email protected] Daniel L. Belnap Daniel Belnap Dan Belnap Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Belnap, Daniel; Belnap, Daniel L.; Belnap, Daniel; and Belnap, Dan, "“And he was Anti-Christ”: The Significance of the Eighteenth earY of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2" (2019). Faculty Publications. 4482. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4482 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “And he was Anti-Christ”: The Significance of the Eighteenth Year of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2 Daniel Belnap For the Nephites, the sixteenth year of the reign of the judges was tremendously difficult. The arrival of the people of Ammon, in itself an incredible disruption of Nephite society, precipitated a bat- tle, which Mormon describes as a “tremendous battle; yea, even such an one as never had been known among all the people in the land from the time Lehi left Jerusalem” (Alma 28:2). The dead, we are told, were not counted due to their enormous number. These events com- pounded the pre-existing struggles that resulted from the sociopolit- 1 ical fallout from the reforms of Mosiah2. Though Alma 30:5 suggests that all is well in Zarahemla during the seventeenth year of the reign of the judges, the events of the next year and half, the eighteenth year, belie this peace. -

Desiring to Believe Wisdom and Political Power

Desiring to Believe Wisdom and Political Power James E. Faulconer ll beginning philosophy students learn that the word “philosophy” means “love of wisdom.” As Socrates argues Ain Plato’s Symposium, we should understand “love” in that etymology to mean “desire” rather than mere adoration. To be a phi- losopher is to desire wisdom, to want it and to seek it. In Alma 32, Alma the younger answers the question of the Zoramite poor, “What shall we do?” (Alma 32:5) by urging them to desire, to desire at least to believe. It doesn’t take much imagination to understand the sermon that follows this admonition as teaching that such a minimal desire will lead to wisdom and fulness of life: the tree of life will spring up in them (Alma 32:41; 33:23). Alma 32 is a sermon on philosophy in its original, broad sense, a sermon on the desire for wisdom and its fruits. But in what does that wisdom consist? I will argue that part of the wisdom of the Alma story, taken as a whole, is that the knowledge of God produces something other than political wisdom. It cannot bring us political peace. When we read and discuss Alma’s sermon to the Zoramites, we sometimes fail to notice that the sermon is two chapters long rather than just one. We more often fail to notice that Amulek’s sermon in chapter 34 begins with an explanatory summary of Alma’s teaching, highlighting what Amulek understood to be Alma’s primary points, and not dividing it artificially as we do because of the break between chapters 32 and 33. -

Disenchanted Lives Apostasy and Ex-Mormonism Among The

© 2015 Edward Marshall Brooks III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DISENCHANTED LIVES: APOSTASY AND EX•MORMONISM AMONG THE LATTER•DAY SAINTS By EDWARD MARSHALL BROOKS III A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School•New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Anthropology Written under the direction of Dorothy L. Hodgson And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Disenchanted Lives: Apostasy and Ex-Mormonism among the Latter-day Saints by EDWARD MARSHALL BROOKS III Dissertation Director: Dorothy L. Hodgson This dissertation ethnographically explores the contemporary phenomenon of religious apostasy (that is, rejecting ones religious faith or church community) among current and former members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (aka Mormons). Over the past decade there has been increasing awareness in both the institutional church and the popular media that growing numbers of once faithful church members are becoming dissatisfied and disenchanted with their faith. In response, throughout Utah post-Mormon and ex-Mormon communities have begun appearing offering a social community and emotional support for those transitioning out of the church. Through fifteen months of ethnographic research in the state of Utah I investigated these events as they unfolded in people’s everyday lives living in a region of the country wholly dominated by the Mormon Church’s presence. In particular, I conducted participant observation in church services, ex-Mormon support group meetings, social networks and family events, as well as in-depth interviews with current and former church members. -

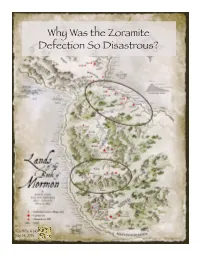

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous?

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous? KnoWhy #143 July 14, 2016 And thus the Zoramites and the Lamanites began to make preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also against the Nephites. Alma 35:11 The Know At the end of Alma 30, the Book of Mormon reports that a group phets, and in consequence were geographically and politically of Nephite dissenters, known as the Zoramites,1 were responsible caught between two major world powers—the Egyptians to the for Korihor’s death (Alma 30:59).2 After receiving news that “the south and the Babylonians to the north. Acting out of fear, and in Zoramites were perverting the ways of the Lord,”3 Alma gathered direct defiance of Jeremiah’s prophetic counsel, King Zedekiah an elite group of missionaries to “preach unto them the word of chose to ally Israel with Egypt.7 This poor decision eventually led God” (Alma 31:1, 7). Yet despite efforts to reclaim these apos- to a Babylonian invasion, which ended with Zedekiah being exiled tates, the Zoramites “cast out of the land” any who believed in the into Babylon after the execution of his family.8 words of Alma and Amulek (Alma 35:6). The Zoramite problem immediately escalated into a series of all-out wars in the land of The Why Zarahemla. Like the kingdom of Judah in Lehi’s time, the Nephites were vul- nerable to enemy incursions on two separate fronts. Understand- When the people of Ammon took in these exiled believers, the ing the high stakes that were involved in this situation—meaning Zoramites stirred up the Lamanites to anger, and together they both the worth of souls among the Zoramites as well as the need made “preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also to maintain them as military allies—can help readers better em- against the Nephites” (Alma 35:11). -

Nibley's Commentary on the Book of Mormon

Nibley’s Commentary On The Book of Mormon Sharman Bookwalter Hummel, Editor Selections from all Four Volumes Teachings of the Book of Mormon by Hugh W. Nibley Volume 1 (Edited from Semester 1, 2) Nibley’s Commentary on The Book of Mormon is based on transcriptions from classes taught by Hugh Nibley, and is published with the permission of the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship and Nibley LLC. It is not sponsored or endorsed by either the Maxwell Institute or Brigham Young University, and represents only the opinions and/or editorial decisions of Hugh Nibley and Sharman B. Hummel.” See http://www.nibleys-commentary.com/ Our thanks to Jimmy Sevilleno [email protected] for e-book conversion Dedication To the Ancient Prophet Moroni, the last Editor of The Book of Mormon, who knew through prophecy the problems of our day, and who as an Angel was assigned to restore the Gospel at the hands of a Modern Prophet Joseph Smith. Contents Preface . 7 About Hugh Nibley . 9 Lecture 1 Introduction . 11 Lecture 2 Introduction . 23 Lecture 3 Introduction . 31 Lecture 4 Introduction . 36 Lecture 5 (Jeremiah) . 43 Lecture 6 Omitted By Editor . 46 Lecture 7 1 Nephi 1; Jeremiah . 47 Lecture 8 1 Nephi . 55 Lecture 9 1 Nephi 1-3, 15 . 58 Lecture 10 (Dead Sea Scrolls). 66 Lecture 11 1 Nephi 4-7 . 70 Lecture 12 1 Nephi 8-11 . 90 Lecture 13 1 Nephi 12-14 . 105 Lecture 14 1 Nephi 15-16 . 125 Lecture 15 1 Nephi 17-19, 22. 139 Lecture 16 2 Nephi 1-4 . -

Lesson 1 Alma 30–35

Book of Mormon, Religion 122 Independent Study Lesson 1 Alma 30–35 The following assignments include various learning Read the student manual commentary “Alma activities, such as questions, lists, essays, charts, 30:15–16: Korihor’s False Teaching” (pages comparisons, contrasts, and surveys. To receive credit 214–15). Explain in writing what you learn for this lesson, you must complete the number of from President Boyd K. Packer and Alma’s assignments indicated below and submit them to example in talking to people who attack the your institute instructor or administrator. You may Church. submit your work either electronically or on paper, handwritten or typed. e. Write how each of the following groups in Alma 30:6, 18–44 responded to Korihor’s Each lesson should take approximately 60–90 minutes teachings: to complete, the same amount of time you would typically spend in a weekly institute class. Since People of Zarahemla reading the scripture block listed in the lesson heading People of Ammon is expected of all institute students prior to class, the estimated time for each assignment does not include People in the land of Gideon the time you need to spend reading the scripture block. Giddonah Complete assignment 7 and any three of the other Alma assignments: f. Write a paragraph explaining how you can follow Alma’s example in verses 37–44 when 1. Alma 30:6–44. Korihor the Anti-Christ confronted with someone who attacks the a. Read the institute student manual Church or its teachings and practices. Share commentaries “Alma 30: Modern-day what you wrote with a family member or a Korihors” and “Alma 30:6: Anti-Christs” friend. -

A Mormon Perspective on CS Lewis

An Abstract of the Thesis of Christopher Edward Garrett for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Interdisciplinary Studies in English. History. and Philosophy presented on March 19. 2001. Title: OfDragons. Palaces. and Gods: A Mormon Perspective on C. S. Lewis Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Wayne C. Anderson During his lifetime C. S. Lewis chose to speak to Christians in plain and simple language that they could understand. Lewis taught and defended truths that he felt were discernible through reason. Morality, free will, and the divinity ofJesus Christ were fundamental to his core beliefs and teachings. His writings have attracted Christian readers from many denominations, including those ofthe Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Through references to Lewis by LDS Church leaders and authors, Mormons have been attracted to Lewis's writings in significant ways. General Authorities have used his thoughts and analogies to illustrate certain gospel principles. Many Latter-day Saints have been impressed by the similarities they perceive between Lewis's theology and Mormonism. Such appreciation has led to Lewis's becoming one ofthe most quoted non-LDS authors in General Conference talks and various Mormon publications. While Lewis was aware ofthe Latter-day Saint religion, he chose to worship in the Church ofEngland. Through his writings, however, he entered into a much broader fellowship with millions ofChristians around the world. His thoughts on "mere Christianity" have created an enormous common ground on which many have stood. Among those who have set foot upon that soil are the Latter-day Saints. Given their open-minded approach to theological reflection, Mormons not only read authors like Lewis but also feel comfortable citing his views on human nature and Christian discipleship. -

Book of Mormon Stories Book of Mormon Stories

BOOK OF MORMON STORIES BOOK OF MORMON STORIES Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah This replaces Book of Mormon Reader Illustrated by Jerry Thompson and Robert T. Barrett © 1978, 1985, 1997 by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 8/96 CONTENTS Chapter Title Page Introduction . 1 1 How We Got the Book of Mormon . 2 2 Lehi Warns the People . 5 3 Lehi Leaves Jerusalem . 6 4 The Brass Plates . 8 5 Traveling in the Wilderness . 13 6 Lehi’s Dream . 18 7 Building the Ship . 21 8 Crossing the Sea . 23 9 A New Home in the Promised Land. 25 10 Jacob and Sherem . 27 11 Enos . 30 12 King Benjamin . 32 13 Zeniff . 36 14 Abinadi and King Noah . 38 15 Alma Teaches and Baptizes . 43 16 King Limhi and His People Escape . 45 17 Alma and His People Escape . 47 18 Alma the Younger Repents. 49 19 The Sons of Mosiah Become Missionaries . 53 20 Alma and Nehor. 54 21 The Amlicites . 56 22 Alma’s Mission to Ammonihah . 58 23 Ammon: A Great Servant . 64 24 Ammon Meets King Lamoni’s Father . 69 25 Aaron Teaches King Lamoni’s Father . 71 26 The People of Ammon . 73 27 Korihor. 75 28 The Zoramites and the Rameumptom . 78 29 Alma Teaches about Faith and the Word of God . 81 30 Alma Counsels His Sons . 82 31 Captain Moroni Defeats Zerahemnah. 85 32 Captain Moroni and the Title of Liberty. -

Book of Mormon Study – Alma 30-31 Online Zoom Sunday School, 12 Jul 2020 (

Book of Mormon Study – Alma 30-31 Online zoom Sunday School, 12 Jul 2020 (https://jayball.name/book-of-mormon-study-lessons) Alma’s Life at a Glance: Year Event Age of Alma the Younger (estimated) 119 BC (Mon 27 Mar) Alma to Zarahemla. (Mosiah 24:18-25) 15-25 Around 100 BC Alma the younger sees angel and is converted. Alma the 33-43 elder is 73. (Mosiah 27:11) Around 91 BC First year of reign of Judges. Alma Elder dies at 82, 42-52 Mosiah dies at 63. (Mosiah 29:44-47) Around 87 BC Alma fights Amlici. (Alma 2:29-31) 46-56 Around 83 BC Alma gives up judgement seat. (Alma 4:16-19) 50-60 Around 77 BC Alma meets Ammon & sons of Mosiah returning home 56-66 from their 14 year mission (Alma 27:16) Around 76 BC Tremendous battle between Lamanites and Nephites 57-67 (Alma 28) Around 74 BC Alma’s confrontation with Korihor (Alma 30). Mission to 59-69 Zoramites (Alma 31). Alma’s teachings to his sons (Alma 36-42). The Zoramite rebellion and Lamanite war with Nephites (Alma 43-44). Around 73 BC Alma taken up. (Alma 45:18) 60-70 Alma 30:3 Stick of Joseph footnote on Law of Moses again. We spoke of this last week. Korihor Anti-Christ Alma 30:6 In verses 15 and 26, Korihor teaches there is no way to know there will be a Christ who shall come. This is the common teaching of anti-Christs. Sherem taught the same thing to Jacob about 400 years earlier.