The Relevance of Religious Freedom Michael K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

THE BOOK of MORMON and the Descent Into Disse T the Book of by Daniel C

Come, Follow Me BOOK OF MORMON THE BOOK OF MORMON AND THE Descent into Disse t The Book of By Daniel C. Peterson n Professor of Islamic Studies and Arabic, Brigham Young University Mormon shows how dissension he Restoration began when the Father and the Son appeared to Joseph Smith, dispelling the “darkness and confusion” that had engulfed him during a and contention “division amongst the people,” a “war of words and tumult of opinions” start, as well as T(see Joseph Smith—History 1:5–20). how to create The revelation of the Book of Mormon followed. unity in Christ’s The Book of Mormon testifies “that Jesus is the Christ” (title page). But it also Church. offers case studies in how dissension arises and how it damages the Church and individuals. It was written “unto the confounding of false doctrines and laying down of contentions, and establishing peace” (2 Nephi 3:12). It doesn’t merely describe the foibles and foolishness of previous generations. It is for our day. We can, therefore, read it as a commentary on our time, a guide and a warning to us. In many ways, the Book of Mormon is a guidebook on how to unify God’s people in the faith, as well as how contention and dissension creep into the Church. Dissenters: Their Motives and Methods Nephite prophets repeatedly condemn contention, strife, and dissension.1 Satan, says Mormon, created contention to “harden the hearts of the people against that which was good and against that which should come” (Helaman 16:22). -

Teachings of the Book of Mormon

TEACHINGS OF THE BOOK OF MORMON HUGH NIBLEY Semester 2, Lecture 54 Alma 30–31 Alma and Korihor Now, if there ever were authentic and inspired passages in the Book of Mormon it’s these [next] chapters we have come to in Alma. We really have something there. Nothing in the whole wide spectrum covered by the Book of Mormon is more significant than what is laid out in Alma 30–35. Wars are tactically territorial, as you know. They always are. That’s absolutely basic—Clausewitz again. It’s the taking and occupying of land that measures an army’s success, but strategically wars are always ideological and they remain that way. The confused alarms and the horrible battles that we get in chapter 28 lead to Alma’s passionate outcry in chapter 29, a very short declaration. Then in chapter 30 everybody is fed up with war for a time. It stops in chapter 30—everybody is exhausted. But how had it all begun? The issues are going to continue. The territorial issues have been settled for the time being, but the ideological issues are still there. Now we have the real conflicts here. Remember, [Ammon’s] religious reforms were pushed by the king and rejected by the majority of his subjects, among whom the Nehor philosophy was the one that was dominant. So when the fighting stopped, the ideological controversy was taken up by the skillful spokesman for Nehor, who was Korihor. His name is very interesting, too, like the chief judge that follows him. We’ll mention it in a minute. -

“And He Was Anti-Christ”: the Significance of the Eighteenth Year of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2 Daniel Belnap

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2019 “And he was Anti-Christ”: The Significance of the Eighteenth earY of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2 Daniel Belnap [email protected] Daniel L. Belnap Daniel Belnap Dan Belnap Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Belnap, Daniel; Belnap, Daniel L.; Belnap, Daniel; and Belnap, Dan, "“And he was Anti-Christ”: The Significance of the Eighteenth earY of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2" (2019). Faculty Publications. 4482. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4482 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “And he was Anti-Christ”: The Significance of the Eighteenth Year of the Reign of the Judges, Part 2 Daniel Belnap For the Nephites, the sixteenth year of the reign of the judges was tremendously difficult. The arrival of the people of Ammon, in itself an incredible disruption of Nephite society, precipitated a bat- tle, which Mormon describes as a “tremendous battle; yea, even such an one as never had been known among all the people in the land from the time Lehi left Jerusalem” (Alma 28:2). The dead, we are told, were not counted due to their enormous number. These events com- pounded the pre-existing struggles that resulted from the sociopolit- 1 ical fallout from the reforms of Mosiah2. Though Alma 30:5 suggests that all is well in Zarahemla during the seventeenth year of the reign of the judges, the events of the next year and half, the eighteenth year, belie this peace. -

Desiring to Believe Wisdom and Political Power

Desiring to Believe Wisdom and Political Power James E. Faulconer ll beginning philosophy students learn that the word “philosophy” means “love of wisdom.” As Socrates argues Ain Plato’s Symposium, we should understand “love” in that etymology to mean “desire” rather than mere adoration. To be a phi- losopher is to desire wisdom, to want it and to seek it. In Alma 32, Alma the younger answers the question of the Zoramite poor, “What shall we do?” (Alma 32:5) by urging them to desire, to desire at least to believe. It doesn’t take much imagination to understand the sermon that follows this admonition as teaching that such a minimal desire will lead to wisdom and fulness of life: the tree of life will spring up in them (Alma 32:41; 33:23). Alma 32 is a sermon on philosophy in its original, broad sense, a sermon on the desire for wisdom and its fruits. But in what does that wisdom consist? I will argue that part of the wisdom of the Alma story, taken as a whole, is that the knowledge of God produces something other than political wisdom. It cannot bring us political peace. When we read and discuss Alma’s sermon to the Zoramites, we sometimes fail to notice that the sermon is two chapters long rather than just one. We more often fail to notice that Amulek’s sermon in chapter 34 begins with an explanatory summary of Alma’s teaching, highlighting what Amulek understood to be Alma’s primary points, and not dividing it artificially as we do because of the break between chapters 32 and 33. -

Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Teacher's Manual

Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Teacher’s Manual Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Teacher’s Manual Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Comments and Suggestions Your comments and suggestions about this manual would be appreciated. Please submit them to: Curriculum Planning 50 E. North Temple St., Rm. 2420 Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3220 USA E-mail: [email protected] Please list your name, address, ward, and stake. Be sure to give the title of the manual. Then offer your comments and suggestions about the manual’s strengths and areas of potential improvement. Cover: Christ with Three Nephite Disciples, by Gary L. Kapp © 1999 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Updated 2003 Printed in the United States of America English approval: 4/03 Contents Lesson Number and Title Page Helps for the Teacher v 1 “The Keystone of Our Religion” 1 2 “All Things According to His Will” (1 Nephi 1–7) 6 3 The Vision of the Tree of Life (1 Nephi 8–11; 12:16–18; 15) 11 4 “The Things Which I Saw While I Was Carried Away in the Spirit” (1 Nephi 12–14) 16 5 “Hearken to the Truth, and Give Heed unto It” (1 Nephi 16–22) 20 6 “Free to Choose Liberty and Eternal Life” (2 Nephi 1–2) 25 7 “I Know in Whom I Have Trusted” (2 Nephi 3–5) 29 8 “O How Great the Goodness of Our God” (2 Nephi 6–10) 33 9 “My Soul Delighteth in the Words of Isaiah” (2 Nephi 11–25) 37 10 “He Inviteth All to Come unto Him” (2 Nephi 26–30) 42 11 “Press Forward with a Steadfastness in Christ” (2 Nephi 31–33) 47 12 “Seek Ye for the Kingdom of God” (Jacob 1–4) 51 13 The Allegory of the Olive Trees (Jacob 5–7) 56 14 “For a Wise Purpose” (Enos, Jarom, Omni, Words of Mormon) 61 15 “Eternally Indebted to Your Heavenly Father” (Mosiah 1–3) 66 16 “Ye Shall Be Called the Children of Christ” (Mosiah 4–6) 71 17 “A Seer . -

Disenchanted Lives Apostasy and Ex-Mormonism Among The

© 2015 Edward Marshall Brooks III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DISENCHANTED LIVES: APOSTASY AND EX•MORMONISM AMONG THE LATTER•DAY SAINTS By EDWARD MARSHALL BROOKS III A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School•New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Anthropology Written under the direction of Dorothy L. Hodgson And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Disenchanted Lives: Apostasy and Ex-Mormonism among the Latter-day Saints by EDWARD MARSHALL BROOKS III Dissertation Director: Dorothy L. Hodgson This dissertation ethnographically explores the contemporary phenomenon of religious apostasy (that is, rejecting ones religious faith or church community) among current and former members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (aka Mormons). Over the past decade there has been increasing awareness in both the institutional church and the popular media that growing numbers of once faithful church members are becoming dissatisfied and disenchanted with their faith. In response, throughout Utah post-Mormon and ex-Mormon communities have begun appearing offering a social community and emotional support for those transitioning out of the church. Through fifteen months of ethnographic research in the state of Utah I investigated these events as they unfolded in people’s everyday lives living in a region of the country wholly dominated by the Mormon Church’s presence. In particular, I conducted participant observation in church services, ex-Mormon support group meetings, social networks and family events, as well as in-depth interviews with current and former church members. -

“Firm in the Faith of Christ”

HIDDEN LDS/JEWISH INSIGHTS - Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Supplement 31 by Daniel Rona Summary Handout =========================================================================================================== “Firm in the Lesson Faith of Christ” 31 Summary Alma 43 – 52 =========================================================================================================== Scripture Alma and his sons preach the word—The Zoramites and other Nephite dissenters become Lamanites—The Lamanites come against Summary: the Nephites in war—Moroni arms the Nephites with defensive armor—The Lord reveals to Alma the strategy of the Lamanites—The Nephites defend their homes, liberties, families, and religion—The armies of Moroni and Lehi surround the Lamanites. [About 74 B.C.] Moroni commands the Lamanites to make a covenant of peace or be destroyed—Zerahemnah rejects the offer, and the battle resumes—Moroni’s armies defeat the Lamanites. [About 74—73 B.C.] Helaman believes the words of Alma—Alma prophesies the destruction of the Nephites—He blesses and curses the land—Alma is taken up by the Spirit, even as Moses—Dissension grows in the Church. [73 B.C.] Amalickiah conspires to be king—Moroni raises the title of liberty—He rallies the people to defend their religion—True believers are called Christians—A remnant of Joseph shall be preserved—Amalickiah and the dissenters flee to the land of Nephi—Those who will not support the cause of freedom are put to death. [Between 73 and 72 B.C.] Amalickiah uses treachery, murder, and intrigue to become king of the Lamanites—The Nephite dissenters are more wicked and ferocious than the Lamanites. Amalickiah incites the Lamanites against the Nephites—Moroni prepares his people to defend the cause of the Christians—He rejoiced in liberty and freedom and was a mighty man of God. -

Table of Contents Hook Dates of the Book of Mormon Volume 2

Table of Contents Hook Dates of the Book of Mormon Volume 2 Hook Date Review Page 3 64 B.C – Helaman – 2,000 Faithful Sons Page 5 - 0 - Nephi the Third - Christ's Birth Page 35 A.D. 34 – Jesus Christ – Savior Visits America page 61 A.D. 333 – Mormon – A Fallen People Page 89 A.D. 421 – Moroni – Plates of Gold Hidden Page 111 Appendix Page 135 The Book of Mormon is Amazing! Page 136 Precious Truths in the Book of Mormon Page 137 Hebrew & English Compared Page 139 Who Was Melchizedek? Page 140 The Famous Prophet Isaiah Page 150 Who are the Gadiantons Today? Page 158 Hagoth’s Possible Route – Map Page 166 The Polynesians Page 167 The Law of Consecration & Order of Enoch Page 183 Answer Key Page 195 Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 1 (Review) The Ten Hook-Dates with Key Personalities and Key Events 2200 B.C. Brother of Jared Tower of Babel 600 B.C. Lehi and Mulek Journeys to America 130 B.C. Mosiah & Benjamin A Covenant People 90 B.C. Alma Missionary Work 73 B.C. Captain Moroni Title of Liberty 64 B.C. Helaman 2,000 Faithful Sons - 0 - Nephi III Christ’s Birth A.D. 34 Jesus Christ Savior Visits America A.D. 333 Mormon A Fallen People A.D. 421 Moroni Plates of Gold Hidden Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 2 Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 3 Summarizing 64 B.C – Helaman – 2,000 Faithful Sons (Comprising Alma Chapter 56 through Helaman Chapter 6) 1. -

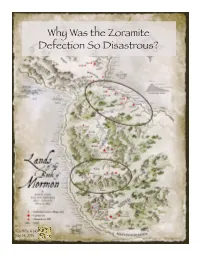

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous?

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous? KnoWhy #143 July 14, 2016 And thus the Zoramites and the Lamanites began to make preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also against the Nephites. Alma 35:11 The Know At the end of Alma 30, the Book of Mormon reports that a group phets, and in consequence were geographically and politically of Nephite dissenters, known as the Zoramites,1 were responsible caught between two major world powers—the Egyptians to the for Korihor’s death (Alma 30:59).2 After receiving news that “the south and the Babylonians to the north. Acting out of fear, and in Zoramites were perverting the ways of the Lord,”3 Alma gathered direct defiance of Jeremiah’s prophetic counsel, King Zedekiah an elite group of missionaries to “preach unto them the word of chose to ally Israel with Egypt.7 This poor decision eventually led God” (Alma 31:1, 7). Yet despite efforts to reclaim these apos- to a Babylonian invasion, which ended with Zedekiah being exiled tates, the Zoramites “cast out of the land” any who believed in the into Babylon after the execution of his family.8 words of Alma and Amulek (Alma 35:6). The Zoramite problem immediately escalated into a series of all-out wars in the land of The Why Zarahemla. Like the kingdom of Judah in Lehi’s time, the Nephites were vul- nerable to enemy incursions on two separate fronts. Understand- When the people of Ammon took in these exiled believers, the ing the high stakes that were involved in this situation—meaning Zoramites stirred up the Lamanites to anger, and together they both the worth of souls among the Zoramites as well as the need made “preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also to maintain them as military allies—can help readers better em- against the Nephites” (Alma 35:11). -

54 III. Alma 55—-56 IV

BM#32 “They Did Obey…Every Word of Command with Exactness” Alma 53-63 I. Introduction II. Alma 53—-54 III. Alma 55—-56 IV. Alma 57—-58 V. Alma 59--61 VI. Alma 62 VII. Alma 63 VIII. Conclusions I. Introduction This lesson is an extension of the prior lesson [BM#31]. Our focus is upon the remaining “War Chapters.” Many readers skip these chapters feeling that there is little to be gained from their reading. In lesson 31, and the current lesson, the position taken is that these chapters symbolically represent the continuing battle between good and evil that began initially in the pre-existence and continues on the earth today. How we survive this battle and along with our loved ones emerge victorious, is the key to our salvation. As we address these remaining chapters, our focus will continue to be on highlighting their challenges and noting how they also apply to our lives as we seek the strength we need to triumph over the forces of evil. While their enemy was visible, ours often is not, but it is no less a real threat to our survival. As I did in BM#31, I will continue to draw upon the insight of John Bytheway. In 2004, he published a book, Righteous Warriors: Lessons from the War Chapters in the Book of Mormon. In 2012, he wrote an article for the on-line LDS magazine: Meridian Magazine. It is titled, Lesson 31, “Firm in the Faith of Christ,” Alma 23-62. It is also his understanding that “within the tactics, the stratagems and the battlefield heroics are numerous spiritual lessons which will help us survive in a time of spiritual and temporal war.” In his article, he summarizes his “favorite spiritual lesson from each of the war chapters.” I will continue the practice, begun in BM#31, of including these summaries at the end of each of the remaining chapters. -

Summary Lesson 32 They Did Obey . . . Every Word of Command With

HIDDEN LDS/JEWISH INSIGHTS - Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Supplement 32 by Daniel Rona Summary Handout =========================================================================================================== “They Did Obey . Every Word Lesson of Command with Exactness” 32 Summary Alma 53 – 63 =========================================================================================================== Scripture The Lamanite prisoners are used to fortify the city Bountiful—Dissensions among the Nephites give rise to Lamanite victories—Helaman Summary: takes command of the two thousand stripling sons of the people of Ammon. [About 64 B.C.] Ammoron and Moroni negotiate for the exchange of prisoners—Moroni demands that the Lamanites withdraw and cease their murderous attacks—Ammoron demands that the Nephites lay down their arms and become subject to the Lamanites. [About 63 B.C.] Moroni refuses to exchange prisoners—The Lamanite guards are enticed to become drunk, and the Nephite prisoners are freed—The city of Gid is taken without bloodshed. [About 63 B.C.] Helaman sends an epistle to Moroni recounting the state of the war with the Lamanites—Antipus and Helaman gain a great victory over the Lamanites—Helaman’s two thousand stripling sons fight with miraculous power and none of them are slain. [About 66—62 B.C.] Helaman recounts the taking of Antiparah and the surrender and later the defense of Cumeni—His Ammonite striplings fight valiantly and all are wounded, but none are slain—Gid reports the slaying and the escape of the Lamanite prisoners. [About 64—63 B.C.] Helaman, Gid, and Teomner take the city of Manti by a stratagem—The Lamanites withdraw—The sons of the people of Ammon are preserved as they stand fast in defense of their liberty and faith.