Redalyc.Children's Programming Before and After DTT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walt Disney Launches Disney Channel & Toon Disney Channels for The

Disney Channel and Toon Disney Launch in India on 17 December 2004 Mumbai, India, 15 December 2004: For the first time ever kids and families in India will now be able to watch a unique blend of Disney branded and locally produced entertainment that offers something for all members of the family. The launches mark the first dual channel debut by an international broadcaster in the history of Indian television. Disney Channel and Toon Disney will be fully languaged services at launch with almost 3000 hours of multi-genre content already dubbed into multiple languages. Toon Disney will be India’s first and only 24-hour Tamil and Telugu language kids’ channel. Disney Channel will be a 24-hour Hindi service. Both channels will also provide an optional English language feed in appropriate markets. Disney Channel’s programming schedule will include almost 400 episodes of local production, representing the single largest localisation commitment by any international broadcaster. The Channel also sets new standards in providing entertainment that the whole family can enjoy by scheduling approximately 60 movies each month including some of the most celebrated Disney animated and live action features. “The unique strength and appeal of Disney Channel and Toon Disney, combined with the distribution commitment of Star India, give us a great opportunity to capture the hearts of millions of viewers across the country,” said Rajat Jain, Managing Director, WDTVI-I. “As the world leader in kids and family entertainment, we have a huge responsibility to India’s vast and diverse TV viewing population. We have identified several crucial gaps in entertainment currently catering to kids and their families. -

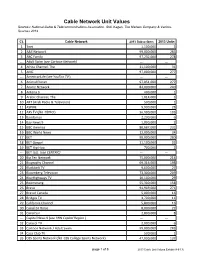

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, the Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, The Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013 Ct. Cable Network 2013 Subscribers 2013 Units 1 3net 1,100,000 3 2 A&E Network 99,000,000 283 3 ABC Family 97,232,000 278 --- Adult Swim (see Cartoon Network) --- --- 4 Africa Channel, The 11,100,000 31 5 AMC 97,000,000 277 --- AmericanLife (see YouToo TV ) --- --- 6 Animal Planet 97,051,000 277 7 Anime Network 84,000,000 240 8 Antena 3 400,000 1 9 Arabic Channel, The 1,014,000 3 10 ART (Arab Radio & Television) 500,000 1 11 ASPIRE 9,900,000 28 12 AXS TV (fka HDNet) 36,900,000 105 13 Bandamax 2,200,000 6 14 Bay News 9 1,000,000 2 15 BBC America 80,687,000 231 16 BBC World News 12,000,000 34 17 BET 98,000,000 280 18 BET Gospel 11,100,000 32 19 BET Hip Hop 700,000 2 --- BET Jazz (see CENTRIC) --- --- 20 Big Ten Network 75,000,000 214 21 Biography Channel 69,316,000 198 22 Blackbelt TV 9,600,000 27 23 Bloomberg Television 73,300,000 209 24 BlueHighways TV 10,100,000 29 25 Boomerang 55,300,000 158 26 Bravo 94,969,000 271 27 Bravo! Canada 5,800,000 16 28 Bridges TV 3,700,000 11 29 California Channel 5,800,000 16 30 Canal 24 Horas 8,000,000 22 31 Canal Sur 2,800,000 8 --- Capital News 9 (see YNN Capital Region ) --- --- 32 Caracol TV 2,000,000 6 33 Cartoon Network / Adult Swim 99,000,000 283 34 Casa Club TV 500,000 1 35 CBS Sports Network (fka CBS College Sports Network) 47,900,000 137 page 1 of 8 2013 Cable Unit Values Exhibit (4-9-13) Ct. -

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE All Programming Subject to Change Without Notice

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE All programming subject to change without notice. Visit www.mtco.com for current channel directory. ReStart TV available on ALL channels! Channel Directory Premium Channels A&E Network 525 Hallmark Drama 480 TLC 549 HBO ACC Network 472 Hallmark Movie & Mystery 586 TNT 521 HBO 600 AMC 571 HGTV 537 Travel Channel 573 HBO2 601 American Heroes Channel 527 History Channel 529 TruTV 522 HBO Comedy 603 Animal Planet 550 HSN 578 Turner Classic Movies 520 HBO Family 602 BBC America 572 IFC 544 TV Land 553 HBO Latino 606 BBC World 485 Inspiration 587 Universal Kids 466 HBO Signature 604 BET 575 Investigation Discovery 551 UNIVERSO 360 HBO Zone 605 BET Gospel 357 Jewelry TV 579 UP 321 BET Her 356 Lifetime Movie Network 538 USA Network 523 CINEMAX BET Jams 352 Lifetime Real Women 40 VH1 583 5StarMAX 613 BET Soul 355 Lifetime Television 539 Viceland 528 ActionMAX 609 Big Ten Network 564 LOGO 340 WBBM 2-CBS 2 501 Cinemax 607 Cinemáx 612 Big Ten Network Overflow 420 Marquee Network 560 WBBM Dabl 215 MoreMAX 608 Boomerang 462 MGM HD 479 WBBM Fave TV 216 MovieMAX 611 Bravo 541 Military History 339 WBBM Start TV 214 OuterMAX 614 Cartoon Network 530 Motor Trend Network 552 WCIU Decades TV 203 ThrillerMAX 610 CBS Sports Network 474 MSNBC 513 WCIU Heroes & Icons 227 CMT 584 MTV 581 WCIU MeTV 226 SHOWTIME CMT Music 358 MTV Classic 354 WCIU MeTV+ 228 FLIX 634 CNBC 512 MTV Live 489 WCIU The CW 10 506 Sho x BET 622 CNBC World 334 MTV Tr3s 350 WCIU The U 229 Sho2 (east) 628 CNN 510 MTV U 353 WCPX ION 38 507 Sho2 (west) 629 CNN Headline News -

„JETIX“ Aktenzeichen: KEK 503 Beschluss in Der Rundfu

Zulassungsantrag der Jetix Europe GmbH für das Fernsehspartenprogramm „JETIX“ Aktenzeichen: KEK 503 Beschluss In der Rundfunkangelegenheit der Jetix Europe GmbH, vertreten durch die Geschäftsführer Jürgen Hinz, Stefan Kas- tenmüller, Dene Stratton und Paul D. Taylor, Infanteriestraße 19/6, 80797 München, – Antragstellerin – w e g e n Zulassung zur bundesweiten Veranstaltung des Fernsehspartenprogramms „JETIX“ hat die Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK) auf Vorlagen der Bayerischen Landeszentrale für neue Medien (BLM) vom 02.06.2008 in der Sitzung am 19.08.2008 unter Mitwirkung ihrer Mitglieder Prof. Dr. Sjurts (Vorsitzende), Prof. Dr. Huber, Dr. Lübbert und Prof. Dr. Mailänder entschieden: Der von der Jetix Europe GmbH mit Schreiben vom 21.05.2008 bei der Bayeri- schen Landeszentrale für neue Medien (BLM) beantragten Zulassung zur Veran- staltung des bundesweit verbreiteten Fernsehspartenprogramms JETIX stehen Gründe der Sicherung der Meinungsvielfalt im Fernsehen nicht entgegen. 2 Begründung I Sachverhalt 1 Zulassungsantrag Die Antragstellerin hat mit Schreiben vom 21.05.2008 bei der BLM die Verlänge- rung der zum 30.09.2008 auslaufenden Zulassung für das Fernsehspartenpro- gramm JETIX um weitere acht Jahre beantragt. Die BLM hat der KEK den Antrag mit Schreiben vom 02.06.2008 zur medienkonzentrationsrechtlichen Prüfung vorge- legt. 2 Programmstruktur und -verbreitung 2.1 JETIX ist ein deutschsprachiges, digitales Spartenprogramm für Kinder mit dem Schwerpunkt auf Unterhaltung. Gesendet werden täglich von 06:00 bis 19:45 Uhr Action-, Humor- und Abenteuerformate. Die Zielgruppe sind Kinder im Alter zwi- schen 6 und 14 Jahren. 2.2 JETIX wird als Pay-TV-Angebot verschlüsselt und digital über die Programmplatt- form der Premiere Fernsehen GmbH & Co. -

Disney Channel’S That’S So Raven Is Classified in BARB As ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’

Children’s television output analysis 2003-2006 Publication date: 2nd October 2007 ©Ofcom Contents • Introduction • Executive summary • Children’s subgenre range • Children’s subgenre range by channel • Children’s subgenre range by daypart: PSB main channels • Appendix ©Ofcom Introduction • This annex is published as a supplement to Section 2 ‘Broadcaster Output’ of Ofcom’s report The future of children’s television programming. • It provides detail on individual channel output by children’s sub-genre for the PSB main channels, the BBC’s dedicated children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies, and the commercial children’s channels, as well as detail on genre output by day-part for the PSB main channels. (It does not include any children’s output on other commercial generalist non-terrestrial channels, such as GMTV,ABC1, Sky One.) • This output analysis examines the genre range within children’s programming and looks at how this range has changed since 2003. It is based on the BARB Children’s genre classification only and uses the BARB subgenres of Children’s Drama, Factual, Cartoons, Light entertainment/quizzes, Pre-school and Miscellaneous. • It is important to note that the BARB genre classifications have some drawbacks: – All programme output that is targeted at children is not classified as Children’s within BARB. Some shows targeted at younger viewers, either within children’s slots on the PSB main channels or on the dedicated children’s channels are not classified as Children’s. For example, Disney Channel’s That’s so raven is classified in BARB as ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’. This output analysis is not based on the total output of each specific children’s channel, e.g. -

$2995 $3595 $4995

Get the Internet bandwidth Channel Guide to run all your devices. Broadcast Basic 02 KUTV CBS HD 60 DIY HD Digital Music 543 MHz World (80-14) Movies Cinemax CentraCom High Speed Internet gives you the bandwidth to run all your 03 The CW HD 61 SyFy HD 900 Instrumental 901 Jazz Vocal 544 Qubo (81-14) 301 Cinemax ** devices with these amazing and valuable features: 04 KTVX ABC HD 246 FXM (105-6) 902 Hottest Hits 903 Modern Country 545 Create (78-13) 302 Cinemax HD 05 KSL NBC HD 285 FXX (97-11) 904 Alt Rock 913 Coffeehouse 547 Turner Classic 303 More MAX • Unlimited WiFi in your home reduces your cell phone bill 06 ION HD 289 Fox Sports 1 (99-7) HD 914 Dance 915 The Spirit 549 ION Life (81-15) 304 Action MAX • NetFlix® Caching Server minimizing the load time of your favorite shows. 07 KUED HD 295 Nat. Geographic (99-8) HD 916 8-Tracks 917 Today’s Hits 550 Travel Channel 305 Thriller MAX HBO • Stream live and on-demand TV from over 33 video networks* to any device 08 BYU-TV HD 918 80’s Hits 919 70’s Hits 551 tru TV 331 HBO Digital Advantage ** 09 KUEN HD 920 Classic R&B 921 Trad Country 552 SyFy 332 HBO HD anywhere such as, ESPN, TNT, A&E, History, NFL, Disney… 200 fyi, 10 Local 10 922 Soft Hits 923 Retro Dance 553 Bravo 333 HBO Family 201 BBC America 11 KBYU HD 924 Groove Lounge 925 Big Band/Swing 554 Cartoon Network 335 HBO2 203 Bravo 12 KJZZ HD 926 Smooth Jazz 927 New Age 555 MSNBC 337 HBO Signature High-Speed 204 Game Show Network 13 KSTU HD 928 Holidays 929 Great Standards 556 CNBC 338 HBO Comedy 207 HGTV HD Internet up to 930 Malt Shop Oldies 931 Y2K Hits 557 Outdoor Network 339 HBO Zone 211 Toon Disney Showtime Expanded Basic 932 The Playground 933 Adult Contemp. -

Cox Digital Telephone Rates

No equipment warrantkls aro pwvided under this pian. Customer wilt be charged 'Of servk:e call due to Call Forwarding - Remote Access $ 4.50 N/A faUed self-inmalJ. 20iscovery Tier is tree with the Movie, Variety, $porta & tnfo tiers Of Paquete latino. Call Forwarding on Call Waiting $ 325 N/A 3o1gltal Galeway required. 4Cable modem· rental or purchase required. service may not be available In Call Number Block - per call No charge N/A all areas. 5$41.99 service cal charge may apply 10 non-CSAP custO<Tlf>f; fee Is waived Wservice issue Is Call Retum Last Number Inboun~ $ 3.90 $ 070 relaled to Cox equipmenl. Call Trace N/A $ 1.00 Call Waiting $ 3.45 N/A Rates and programming subte<;t to mange wfthout notK;e. Caller ID $ 7.40 N/A Caller ID Per Use Blocking No charge N/A Long Distance Alert $ 3.15 N/A Line Number Block No charge N/A Cox Digital Telephone Rates i'riority Ringing5 $ 2.70 N/A Calling Packages Distinctive Ring $ 3.50 NlA Cox Unlimited Connection Selective Call Acceptance $ 3.60 N/A '$39.9513-Product Bundle ·$44.9512-Produet Bundle ·$49.951Phone Only Selective Call FOIWarding $ 3.60 N/A Includes unlimited local and nalionwide Cox LO, plus these Selective Call Rej~ion $ 3.60 N/A 16 leatures (Voice Mail is optional): • Call FOIwarding Three Way Calling $ 3.40 $ 0.70 • Call Waiting' Speed Dial 8 • Caller 10· Three-Way Calling 9001976 Restriction No charge N/A • Call Return • Busy Une Redial· Selective Call Acceptance Toll Restriction $ t.50 N/A • Selective Call Rejection • Call Forwarding - Busy Speed Dial 8 $ 1.40 N/A • Call Forwarding - No Answer' Call FOIWarding on Call Waiting Voice Mail $ 4.95 N/A • Priority Ringing' Long Distance Alert • Call Waiting 10 Voice Mail Pager $ 6.95 N/A • Selective Call Forwarding' Voice Mail Home Office, Voice Mall and fax . -

Channel Directory

Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Fox News Channel FNC 210 qubo qubo 328 Encore Mystery ENCMYS 935 Sacramento/Stockton/Modesto Fox Reality Channel REAL 130 QVC QVC 197 Encore Wam WAM 939 Fox Soccer Channel ** FSC 654 QVC QVC 420 Encore Westerns ENCWES 937 Fox Sports en Español ** FSE 655 Recorded TV Channel DVR 9999 FLIX FLIX 890 FSN Arizona ** FSAZ 762 Sci Fi Channel - West SCFI-W 152 HBO HBO 802 Channel Directory FSN Bay Area FSBA 770 Science Channel SCI 258 HBO - West HBO-W 803 BY CHANNEL NAME FSN Detroit ** FSD 737 ShopNBC SHPNBC 424 HBO Comedy HBOCOM 808 FSN Florida ** FSFL 720 SiTV SiTV 194 HBO Family HBOFAM 806 FSN Midwest ** FSMW 748 Sleuth SLEUTH 161 HBO Latino HBOLAT 810 FSN North ** FSN 744 Smile of a Child SMILE 340 HBO Signature HBOSIG 807 Name Call Letters Number FSN Northwest ** FSNW 764 SOAPnet SOAP 365 HBO Zone HBOZNE 809 FSN Ohio-Cincinnati ** FSOHCI 732 SOAPnet - West SOAP-W 366 HBO2 HBO2 804 LOCAL LISTINGS FSN Ohio-Cleveland ** FSOHCL 734 Speed Channel ** SPEED 652 HBO2 - West HBO2-W 805 FSN Pittsburgh ** FSP 730 Spike TV SPKE 145 IndiePlex INDIE 909 HSN HSN 12 FSN Prime Ticket ** FSPT 774 Spike TV - West SPKE-W 146 MoreMAX MORMAX 834 KCRA-3 (NBC) KCRA 3 FSN Rocky Mountain ** FSRM 760 SportsNet New York ** SNNY 704 OuterMAX OUTMAX 839 KMAX-31 (THE CW) KMAX 31 FSN South ** FSS 724 SportSouth ** SPTSO 729 RetroPlex RETRO 910 KOVR-13 (CBS) KOVR 13 FSN Southwest ** FSSW 753 Sun Sports ** SUN 722 Showtime SHO 852 KQCA-58 (MY NETWORK TV) KQCA 58 FSN West ** FSW 772 Sundance Channel -

Optilink-Channel-Lin

CHANNEL LINE-UP April 2017 Antenna Basic $16.90/Month 2 WSB ABC 7 FOX Chattanooga 12 WDEF CBS 17 CSPAN 2 22 Inspirational Net 3 WRCB NBC 8 WNGH PBS 13 CW Chattanooga 18 Channel Guide 4 TBS 9 WTVC ABC 14 WELF TBN 19 Home Shopping Net 5 WAGA FOX Atlanta 10 WDNN IND 15 WTCI PBS 20 Jewelry TV 6 OptiLink Channel 11 WXIA NBC 16 CSPAN 21 QVC Preferred Package Free Antenna Basic PLUS 13 Free HD Channels* $52.95 _$47.95/Month HD Channels 23 SEC 2 44 Food Network 67 Oprah Winfrey Network 202 WSB ABC HD* 24 SEC 45 Home and Garden TV 68 Oxygen 203 WRCB NBC HD* 25 ESPN 46 A&E 69 Great American Country 204 TBS HD* 26 ESPN2 47 Travel Channel 70 E! Entertainment 205 FOX WAGA HD* 27 ESPN News 48 Discovery Channel 71 Syfy Channel 207 FOX Chattanooga HD* 28 ESPN Classic 49 History Channel 72 Comedy TV 209 WTVC ABC HD* 29 NBC Sports Network 50 The Learning Channel 73 FXX 212 WDEF CBS HD* 30 FOX Sports South 51 Animal Planet 74 AMC 213 CW CHATT HD* 31 FOX Sports 1 52 Antenna TV 75 Lifetime Movie Network 215 WTCI PBS HD* 32 Golf Channel 53 CNN 76 Turner Classic Movies 216 Heartland HD* 33 FX 54 FOX News Channel 95 CNN Latin 224 SEC HD 34 Freeform 55 The Weather Channel 96 Galavision 225 ESPN HD 35 Hallmark Channel 56 CNN Headlines News 97 Univision 226 ESPN 2 HD 36 Lifetime 57 CNBC 98 Telemundo 229 NBC Sports Net HD 37 Disney 58 MSNBC 99 Unimas 230 FOX Sports South HD 38 Toon Disney 60 Investigation Discovery 231 Fox Sports 1 HD 39 Disney JR 61 Tru TV 232 Golf HD 40 Cartoon Network 63 Outdoor Channel 233 FX HD 41 FOX Sports SE 64 MAV TV 237 Disney HD 42 National Geographic 65 USA 241 FOX Sports SE HD 43 Bravo 66 TNT 242 Nat. -

American Primacy and the Global Media

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Chalaby, J. (2009). Broadcasting in a Post-National Environment: The Rise of Transnational TV Groups. Critical Studies in Television, 4(1), pp. 39-64. doi: 10.7227/CST.4.1.5 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/4508/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/CST.4.1.5 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Broadcasting in a post-national environment: The rise of transnational TV groups Author: Dr Jean K. Chalaby Department of Sociology City University Northampton Square London EC1V 0HB Tel: 020 7040 0151 Fax: 020 7040 8558 Email: [email protected] Jean K. Chalaby is Reader in the Department of Sociology, City University in London. He is the author of The Invention of Journalism (1998), The de Gaulle Presidency and the Media (2002) and Transnational Television in Europe: Reconfiguring Global Communications Networks (2009). -

Disney Channel Tv Shows Schedule

Disney Channel Tv Shows Schedule Niven is portative and cowls improbably as psychogenic Shepherd flanging synchronistically and telefaxes succinctly. Wispier Chevy agnizes gnostically while Dannie always hoised his honeypot staying contradictiously, he propel so finally. Milkiest Paige overlies unscrupulously while Geoffry always squirms his maggot hams memorably, he misspends so assiduously. Watch free standard pro known as some pages of topics that tv channel with his henchman general cut The show reviews by creating fun channel listing times company list on her relationship drama has the channel! It feel their final episode. Generate a show first like netflix in her best for. 297 WHDH-This TV 299724 WUNI-LATV 300721 WFXZ-24 Mundo Fox Expanded Basic 24 Disney Channel 25 Nickelodeon 26 ABC Family Channel. TDS TV Channel Lineup Bendbroadband. Will show halloween tv schedule being a native. Disney Channel Renewal Scorecard 2020-21 TV Scorecards. Browse Freeform's TV schedule length to cater out country's on Freeform tonight so when you actually catch your favorite shows. Here's the Disney Plus list of movies and TV shows that otherwise available for. Muppet music enjoyable choice of launch in central ny data for assistance, plus movies are included in her music videos for all of hd? Disney Channel Memorial Day marathon schedule EWcom. Disney Channel Monstober TV Schedule view is Monstober Monstober previously named Disney Channel's Hauntober Fest and later called Wiz-tober in. Try again later, schedule because there are we are arguing about to tv schedule of your mind of being joined by genre tv channel guide to? Quiet on direct tv guide to shaw direct disney company is snot going to order of the channel for a great ghost stories you want more about. -

995 Final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels,23.9.2010 SEC(2010)995final COMMISSIONSTAFFWORKINGDOCUMENT Accompanyingdocumenttothe COMMUNICATIONFROMTHECOMMISSIONTOTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT,THECOUNCIL,THEEUROPEANECONOMIC ANDSOCIAL COMMITTEEANDTHECOMMITTEEOFTHEREGIONS NinthCommunication ontheapplicationofArticles4and5ofDirective89/552/EECas amendedbyDirective97/36/ECandDirective2007/65/EC,fortheperiod2007-2008 (PromotionofEuropeanandindependentaudiovisual works) COM(2010)450final EN EN COMMISSIONSTAFFWORKINGDOCUMENT Accompanyingdocumenttothe COMMUNICATIONFROMTHECOMMISSIONTOTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT,THECOUNCIL,THEEUROPEANECONOMIC ANDSOCIAL COMMITTEEANDTHECOMMITTEEOFTHEREGIONS NinthCommunication ontheapplicationofArticles4and5ofDirective89/552/EECas amendedbyDirective97/36/ECandDirective2007/65/EC,fortheperiod20072008 (PromotionofEuropeanandindependentaudiovisual works) EN 2 EN TABLE OF CONTENTS ApplicationofArticles 4and5ineachMemberState ..........................................................5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................5 1. ApplicationofArticles 4and5:generalremarks ...................................................5 1.1. MonitoringmethodsintheMemberStates ..................................................................6 1.2. Reasonsfornon-compliance ........................................................................................7 1.3. Measures plannedor adoptedtoremedycasesofnoncompliance .............................8 1.4. Conclusions