Contemplating Money and Wealth in Monastic Writing C. 1060–C. 1160 Giles E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Historian of Malmesbury, of Crusade

William of Malmesbury, Historian of Crusade Rod Thomson University of Tasmania William of Malmesbury (c.1096 - c.1143), well known as one of the greatest historians of England, is not usually thought of as a historian of crusadingl His most famous work, the Gesta Regum Anglorum, in five books subdivided into 449 chapters, covers the history of England from the departure of the Romans until the early 1120s.2 But there are many digressions, most of them into Continental history; William is conscious of them and justifies them in explicit appeals to the reader. 3 Some provide necessary background to the course of English affairs, some are there for their entertainment value, and some because of their intrinsic importance. William's account of the First Crusade comes into the third category. It is the longest of all the diversions, occupying the last 46 of the 84 chapters which make up Book IV, or about 12% of the complete Gesta Regum. This is as long as a number of independent crusading chronicles (such as Fulcher's Gesta Francorum Iherosolimitanum Peregrinantium in its earliest edition, or the anonymous Gesta Francorum) and the story is brilliantly told. It follows the course of the Crusade from the Council of Clermont to the capture of Jerusalem, continuing with the so-called Crusade of H aI, and the deeds of the kings of Jerusalem and other great magnates such as Godfrey of Lorraine, Bohemond of Antioch, Raymond of Toulouse and Robert Curthose. The detailed narrative concludes in 1102; some scattered notices come down to c.1124, close to the writing of the Gesta, with a very little updating carried out in H34-5. -

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 150/Friday, August 3, 2018/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 150 / Friday, August 3, 2018 / Notices 38161 Community Community map repository address Canadian County, Oklahoma and Incorporated Areas Project: 12–06–1030S Preliminary Date: February 8, 2018 City of El Reno ......................................................................................... Municipal Building, 101 North Choctaw Avenue, El Reno, OK 73036. Aransas County, Texas and Incorporated Areas Project: 15–06–0811S Preliminary Date: March 16, 2018 City of Aransas Pass ................................................................................ City Hall, 600 West Cleveland Boulevard, Aransas Pass, TX 78336. San Patricio County, Texas and Incorporated Areas Project: 15–06–0811S Preliminary Date: March 16, 2018 City of Aransas Pass ................................................................................ City Hall, 600 West Cleveland Boulevard, Aransas Pass, TX 78336. [FR Doc. 2018–16666 Filed 8–2–18; 8:45 am] 97.048, Disaster Housing Assistance to Brown Fund; 97.032, Crisis Counseling; BILLING CODE 9110–12–P Individuals and Households In Presidentially 97.033, Disaster Legal Services; 97.034, Declared Disaster Areas; 97.049, Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA); Presidentially Declared Disaster Assistance— 97.046, Fire Management Assistance Grant; DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND Disaster Housing Operations for Individuals 97.048, Disaster Housing Assistance to and Households; 97.050, Presidentially Individuals and Households In Presidentially SECURITY Declared Disaster Assistance to Individuals -

ASPECTS of Tile MONASTIC PATRONAGE of Tile ENGLISH

ASPECTS OF TIlE MONASTIC PATRONAGE OF TIlE ENGLISH AND FRENCH ROYAL HOUSES, c. 1130-1270 by Elizabeth M. Hallani VC i% % Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in History presented at the University of London. 1976. / •1 ii SUMMARY This study takes as its theme the relationship of the English and French kings and the religious orders, £.1130-1270, Patronage in general is a field relatively neglected in the rich literature on the monastic life, and royal patronage has never before been traced over a broad period for both France and England. The chief concern here is with royal favour shown towards the various orders of monks and friars, in the foundations and donations made by the kings. This is put in the context of monastic patronage set in a wider field, and of the charters and pensions which are part of its formaL expression. The monastic foundations and the general pattern of royal donations to different orders are discussed in some detail in the core of the work; the material is divided roughly according to the reigns of the kings. Evidence from chronicles and the physical remains of buildings is drawn upon as well as collections of charters and royal financial documents. The personalities and attitudes of the monarchs towards the religious hierarchy, the way in which monastic patronage reflects their political interests, and the contrasts between English and French patterns of patronage are all analysed, and the development of the royal monastic mausoleum in Western Europe is discussed as a special case of monastic patronage. A comparison is attempted of royal and non-royal foundations based on a statistical analysis. -

Orderic Vitalis

Orderic Vitalis Date of Birth 16 February 1075 Place of Birth Atcham, near Shrewsbury Date of Death Unknown; probably after 1142, on 13 July Place of Death Abbey of St Evroul, France Biography Orderic was born in Mercia in 1075 to a Norman father and English mother. His father was a clerk in the retinue of Roger of Montgomery, later the earl of Shrewsbury. Orderic was given a rudimentary educa- tion at a newly-built local abbey, before his father sent him away at the age of ten to the abbey of St Evroul, never to see him again. Despite his importance as a historian, little is known of Orderic except a few details that can be gleaned from his own work, so his life at the abbey is something of a mystery. His studies at St Evroul prob- ably lasted until he was 18, when he was made a deacon. However, he continued working with books throughout his life, spending much time in the scriptorium, first copying others’ works, then composing his own. His output was considerable, as many manuscripts bearing his handwriting survive, and these include lives of saints, liturgies, hymns, biographies and histories. Orderic spent the rest of his life at the abbey, only venturing into the wider world on abbey business, from which experiences spring some of his most powerful descriptive passages. This meant that he was not immune to the realities of life outside; the turbulent politics of the locality ensured that could not be the case. Thus, he was well able to understand the political backgrounds to the events he described in the Ecclesiastical history, while his travels to other ecclesiastical insti- tutions enabled him both to see the places he was describing, and to exchange ideas with others. -

The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory Georg Strack Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich

medieval sermon studies, Vol. 56, 2012, 30–45 The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory Georg Strack Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich Scholars have dealt extensively with the sermon held by Urban II at the Council of Clermont to launch the First Crusade. There is indeed much room for speculation, since the original text has been lost and we have to rely on the reports of it in chronicles. But the scholarly discussion is mostly based on the same sort of sources: the chronicles and their references to letters and charters. Not much attention has been paid so far to the genre of papal synodal sermons in the Middle Ages. In this article, I focus on the tradition of papal oratory, using this background to look at the call for crusade from a new perspective. Firstly, I analyse the versions of the Clermont sermon in the crusading chronicles and compare them with the only address held by Urban II known from a non-narrative source. Secondly, I discuss the sermons of Gregory VII as they are recorded in synodal protocols and in historiography. The results support the view that only the version reported by Fulcher of Chartres corresponds to a sort of oratory common to papal speeches in the eleventh century. The speech that Pope Urban II delivered at Clermont in 1095 to launch the First Crusade is probably one of the most discussed sermons from the Middle Ages. It was a popular motif in medieval chronicles and is still an important source for the history of the crusades.1 Since we only have the reports of chroniclers and not the manuscript of the pope himself, each analysis of this address faces a fundamental problem: even the three writers who attended the Council of Clermont recorded three different versions, quite distinctive both in content and style. -

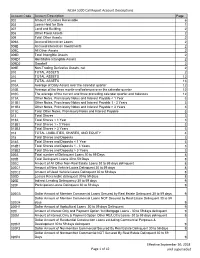

NCUA 5300 Call Report Account Descriptions Page 1 of 42 Effective

NCUA 5300 Call Report Account Descriptions Account Code Account Description Page 002 Amount of Leases Receivable 6 003 Loans Held for Sale 1 007 Land and Building 2 008 Other Fixed Assets 2 009 Total Other Assets 2 009A Accrued Interest on Loans 2 009B Accrued Interest on Investments 2 009C All Other Assets 2 009D Total Intangible Assets 2 009D1 Identifiable Intangible Assets 2 009D2 Goodwill 2 009E Non-Trading Derivative Assets, net 2 010 TOTAL ASSETS 2 010 TOTAL ASSETS 12 010 TOTAL ASSETS 13 010A Average of Daily Assets over the calendar quarter 12 010B Average of the three month-end balances over the calendar quarter 12 010C The average of the current and three preceding calendar quarter-end balances 12 011A Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable < 1 Year 3 011B1 Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable 1 - 3 Years 3 011B2 Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable > 3 Years 3 011C Total Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable 3 013 Total Shares 3 013A Total Shares < 1 Year 3 013B1 Total Shares 1 - 3 Years 3 013B2 Total Shares > 3 Years 3 014 TOTAL LIABILITIES, SHARES, AND EQUITY 4 018 Total Shares and Deposits 3 018A Total Shares and Deposits < 1 Year 3 018B1 Total Shares and Deposits 1 - 3 Years 3 018B2 Total Shares and Deposits > 3 Years 3 020A Total number of Delinquent Loans 30 to 59 Days 8 020B Total Delinquent Loans 30 to 59 Days 8 020C Amount of All Other Non-Real Estate Loans 30 to 59 days delinquent 8 020C1 Amount of New Vehicle Loans Delinquent 30 to 59 days 8 020C2 Amount of Used -

T2 R1.5 Femoral Nailing System

T2 R1.5 Femoral Nailing System Operative Technique Femoral Nailing System Contributing Surgeons Prof. Dr. med. Volker Bühren Chief of Surgical Services Medical Director of Murnau Trauma Center Murnau Germany Joseph D. DiCicco III, D. O. Director Orthopaedic Trauma Service Good Samaritan Hospital Dayton, Ohio Associate Clinical Professor of Orthopeadic Surgery Ohio University and Wright State University USA Thomas G. DiPasquale, D. O. Medical Director, Orthopedic Trauma Services Director, Orthopedic Trauma Fellowship and This publication sets forth detailed Orthopedic Residency Programs recommended procedures for using York Hospital Stryker Osteosynthesis devices and York instruments. USA It offers guidance that you should heed, but, as with any such technical guide, each surgeon must consider the particular needs of each patient and make appropriate adjustments when and as required. A workshop training is required prior to first surgery. All non-sterile devices must be cleaned and sterilized before use. Follow the instructions provided in our reprocessing guide (L24002000). Multi-component instruments must be disassembled for cleaning. Please refer to the corresponding assembly/ disassembly instructions. See package insert (L22000007) for a complete list of potential adverse effects, contraindications, warnings and precautions. The surgeon must discuss all relevant risks, including the finite lifetime of the device, with the patient, when necessary. Warning: Fixation Screws: Stryker Ostreosynthesis bone screws are not approved or intended for screw attachment or fixation to the posterior elements (pedicles) of the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine. 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 Implant Features 4 Instrument Features 6 References 6 2. Indications, Precautions and Contraindications 7 Indications 7 Precautions 7 Relative Contraindications 7 3. -

Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11Th-12Th Centuries

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 5 2019 The Comedia Normannorum: Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11th-12th Centuries Patrick Stroud Wabash College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Stroud, Patrick (2019) "The Comedia Normannorum: Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11th-12th Centuries," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 5 , Article 10. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol5/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 5 THE COMEDIA NORMANNORUM: NORMAN IDENTITY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE 11TH-12TH CENTURIES PATRICK STROUD, WABASH COLLEGE MENTOR: STEPHEN MORILLO Introduction—How Symbols and Ethnography Tie to Historical Myth Since the 1970s, historians have tried many different methodologies for exploring texts. Because multiple paradigms tempt the historian’s gaze, medieval texts can often befuddle readers in their hagiographies and chronologies. At the same time, these texts also give the historian a unique opportunity in the form of cultural insight. In his 1995 work Making History: The Normans and their Historians in Eleventh-Century Italy, Kenneth Baxter Wolf discusses a text’s role in medieval historiography. A professor of History at Pomona College, Wolf divides historical commentary on medieval primary sources into two ends of a spectrum. While one end worries itself on the accuracy and classical “truth” of a source, the other end, postmodern historiography, uses historical records “to tell us how the people who wrote them conceived of the events occurring in the world around them.”1 The historian treats a medieval text as a launching pad for cultural analysis. -

Harold Godwinson in 1066

Y7 Home Learning HT2 This term we are studying the Norman conquest of 1066 and onwards. An event which changed how England looked and worked for years to come. The tasks below relate to each week of study, and should only be completed depending on what your teacher asks. Week 1 Task 1 Watch this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cKGz- st75w&ab_channel=BBCTeach Think: How different was Saxon England to today’s England? Answer these questions below: 1. What did the Saxons do for entertainment? 2. What did people do for medicine? 3. What is the main religion in Britain now? How different do you think Saxon Britain is compared to today? Answer in your books. Task 2 Read the information above to connect the correct descriptions to the correct job title in your books, using the words below. Job Titles: Descriptions: Peasant Farmers Old Wise men Slaves Bought and sold Thegns (pronounced Thane) Those who rent farms Earls Aristocrats The Monarchy Holds more land than peasants The Witan Advisors Is owed service Lives in a manor house Relationships are based on loyalty 10% of the population Decide the new King Week 2 Task 3 Look at the image below: This image is a tapestry, showing an image of King Harold Godwinson in 1066. There are 9 items in the tapestry that have been circled. Explain in your book how each of these 9 people/items show Harold as a powerful king. E.g. The orb shows Harold as powerful because… Task 4 Read the source of information about Harold Godwinson below. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME – WINTER – JULY TO DECEMBER 1978 .................................................... 3 FIELD MEETING AT LONGTOWN AND CRASSWALL, 19TH MARCH, 1978 ....................... 4 THE GRANDMONTINE PRIORY OF ST MARY AT CRASWALL.......................................... 5 LONGTOWN CASTLE ........................................................................................................ 10 IN SEARCH OF ST ETHELBERT’S WELL, HEREFORD .................................................... 14 NOTES ON MILLS FROM ESTATE LEDGERS .................................................................. 16 EXCAVATIONS AT THE COUNTY HOSPITAL, BURIAL GROUND OF ST GUTHLAC’S MONASTERY – MAY 1978 ................................................................................................. 16 EWYAS HAROLD ............................................................................................................... 17 FORGE GARAGE, WORMBRIDGE .................................................................................... 20 MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ELECTED FOR 1978 ................................................... 23 ACTIVITIES OF OTHER SOCIETIES ................................................................................. 23 HAN 35 Page 1 HEREFORDSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL NEWS WOOLHOPE CLUB ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SECTION No. 35 June 1978 EDITORIAL Many members will probably have seen photographs of -

Reimbursement to American Red Cross for Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne

United States Government Accountability Office GAO Report to Congressional Committees May 2006 DISASTER RELIEF Reimbursement to American Red Cross for Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne a GAO-06-518 May 2006 DISASTER RELIEF Accountability Integrity Reliability Highlights Reimbursement to American Red Cross Highlights of GAO-06-518, a report to for Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, congressional committees and Jeanne Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found In accordance with Public Law 108- The signed agreement between FEMA and the Red Cross properly 324, GAO is required to audit the established criteria for the Red Cross to be reimbursed for allowable reimbursement of up to $70 million expenses for disaster relief, recovery, and emergency services related to of appropriated funds to the hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne. The Red Cross incurred American Red Cross (Red Cross) $88.6 million of allowable expenses. for disaster relief associated with 2004 hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne. The audit was Consistent with the law, the agreement explicitly provided that the Red performed to determine if (1) the Cross would not seek reimbursement for any expenses reimbursed by other Federal Emergency Management federal funding sources. GAO identified $0.3 million of FEMA paid costs that Agency (FEMA) established the Red Cross properly deducted from its reimbursement requests, so as not criteria and defined allowable to duplicate funding by other federal sources. The Red Cross also reduced its expenditures to ensure that requested reimbursements by $60.2 million to reflect private donations for reimbursement claims paid to the disaster relief for the four hurricanes, for a net reimbursement of Red Cross met the purposes of the 28.1 million. -

Gallop to Gomorrah How Most Catholic

Gallop to Gomorrah: How Most Catholic Universities and Colleges Allow the Homosexual Movement to Subvert Moral Values A Special Report May 13, 2016 by Bentley G. Hatchett II and John Ritchie TFP Student Action www.TFPStudentAction.Org "Not to oppose error is to approve it; and not to defend truth is to suppress it; and indeed to neglect to confound evil men, when we can do it, is no less a sin than to encourage them." – Pope St. Felix III Special Report For several years, Tradition Family Property Student Action has documented the existence of pro-homosexual clubs and activities at Catholic universities and colleges in America. The present report brings previous TFP research up-to-date and serves to inform and alert fellow Catholics —especially students and parents— about the profound moral crisis shaking Catholic higher education. Synopsis of Findings Since 2012 the number of Catholic universities and colleges with pro-homosexual clubs and programs has risen from 111 to 130, representing a 9% growth. According to the U. S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, there are 218 Catholic universities and colleges in America (excluding seminaries and religious institutes). Research shows that 59% of those 218 institutions have active pro-homosexual advocacy clubs and activities, which often promote the ideas of the Sexual Revolution and its ever- expanding Culture of Death. In short, instead of defending moral values, many Catholic centers of higher learning are allowing —and in some cases fostering and financing— the sinful gallop towards Gomorrah.